HUMAN RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT AND ITS LINKS TO THE LABOUR

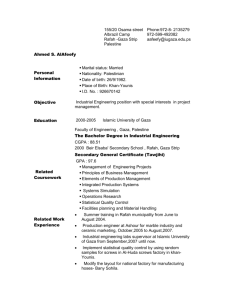

advertisement