PANORAMA From policy to practice From policy to practice

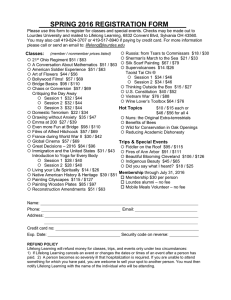

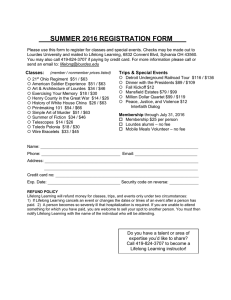

advertisement