THE FIRST YEAR EXPERIENCE by MARGARET HIGGINS

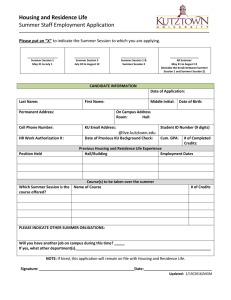

advertisement