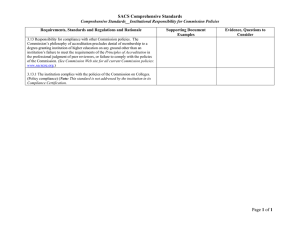

E G VIDENCE UIDE

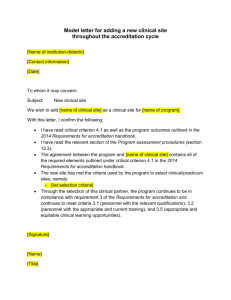

advertisement