San Joaquin Valley Fair Housing and Equity Assessment

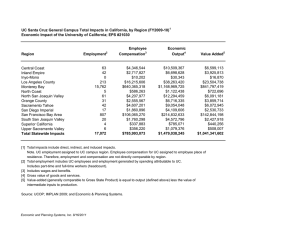

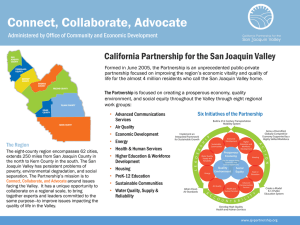

advertisement