9 How Sustainable is the Communalizing Discourse of ‘New’ Conservation?

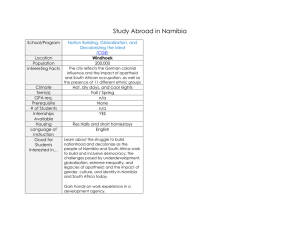

advertisement