Neoliberalisation and Place: Deconstructing and Reconstructing Borders Philip G. Cerny

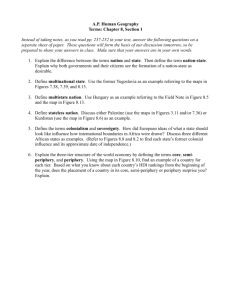

advertisement