The Cry of the Owl Sleeping with half open eyes:

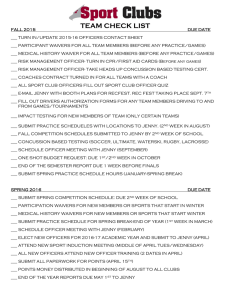

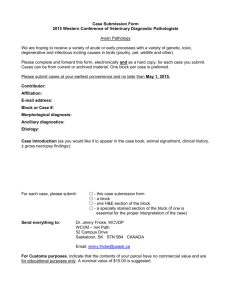

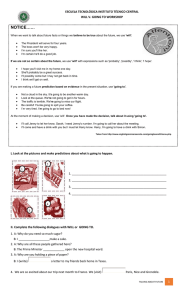

advertisement