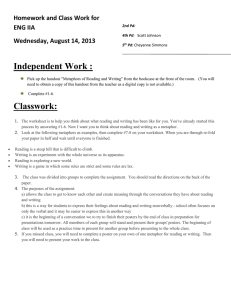

Problems and Promise of Metaphor in Organizations

advertisement