STRENGTHENING REGIONAL CAPACITY IN INFANT-FAMILY AND EARLY CHILDHOOD

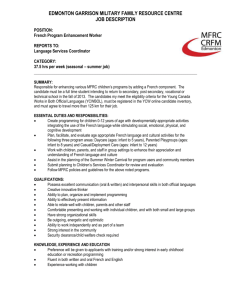

advertisement