AC

advertisement

AC

c

St

c

HURTING IN THE HEARTLAND:

8,

‘B

1

ACCESS TO HEALTH CAREIN THE SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY

A REPORTAND RECOMMENDATIONS

.g

‘c

a

JOEL DIRINGER, JD, MPH

CYNTHIA ZIOLKOWSKI, MA

NOE PARAMO, JD

Rural Health Advocacy Institute

California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation

c

California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation

2424 “ K Street, 1st Floor

Sacramento, CA 95816

Telephone: 916-446-7904

Fax: 916-446-1416

Copyright 0 1996 by the Rural Health Advocacy Institute and the California Rural Legal

Assistance Foundation

Reproduction of the text of this publication is permitted with credit

to the Rural Health Advocacy

Institute and California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation.

2nd'Printingof Hurting in the Heartland is generously provided byThe California Endowment.

-

The RuralHealth Advocacy Institute is a joint projectof California Rural Legal Assistance

(CFUA) and the CRLA Foundation. The principal goals of the Rural Health AdvocacyInstitute

are to:

0

develop, maintain and disseminate information on the health of California's rural and

agricultural communities;

0

identlfy and train community leaders in advocating for healthier communities through

healthier environments and working conditions

and greater access to preventive programs

and prima^^ health care;

advocate onbehalf of rural and agricultural communities to ensure healthier lives,

environment and working conditions.

Joel Diringer, ID, MPH ,was director of the Rural Health AdvocacyInstitute. Cynthia

Ziokowski, MA was a researchassociate at the Institute and Noe Paramo, ID, is a community

outreach worker in the Modesto office of CWA.

..

Diringer is currently Senior

a

Program Officer &th The California Endowment (818-7033311, ext. 282).

Mr.

r

L

Page iii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This report was made possible through a generous grant from Blue

Cross of California in

advancement of its mission to assist and support organizations which are engaged in helping all

Californians gain accessto health care. With the changes in the system, Blue Cross is applyingits

problem solving capacity in partnerships with organizations suchas the Rural Health Advocacy

Institute to reach our mutual goal - to give Californians the opportunityto lead healthier lives.

Invaluable assistancewas obtained from dozensof persons who participated in focus

groups and advisory committees, and who provided input on technical, policy, and community

issues. Special thanks goes to Geraldine Dallek, formerly of the Center for Health Care Rights,

Dr. Andrew Bindman and Dennis Keaneof the UCSF Primary Care Research Center, Laurie True

and Marion Standishof FoodPolicy Advocates, Betty Wetters of

the Merced County Health

Department, Eliezer Riscoof United Health Centersof the San Joaquin Valley, Jane Walsh of the

Western Consortium for Public Health, Matt Freebe, student intern from California Polytechnic

State University, staEat the Hospital Council FoundationofNorthem and Central California, and

Christine Awtreyof the San Joaquin County Councilof Governments. The staff of Department of

Health Services were also extremelyhelpll in obtaining relevant data.

We dedicate this report to those persons whoare doing the backbreakingwork of

planting, tending, harvesting, and packaging our food, but whoare left out of our elaborate

system of health care. Farmworkers are the backbone of our agricultural wealth, yet they remain

hurting in our heartland of abundance. This report identifies the issues confronting farmworkers

and the rural poor, and provides solutionsto their isolation.

"

r

L

Hurting in the Heartland:Access to Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page v

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

iii

LISTOFTABLES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

viii

LISTOFFIGURES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ix

EXECUTJYESUMMARY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

xi

I. INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

METHODOLOGY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5

II.

111. IMPEDIMENTSTO IMPROVING HEALTH IN THE HEARTLAND . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 1

A. EXISTING HEALTH PROGRAMS ARE SERIOUSLY UNDERUTILIZED

ANDUNDERFUNDED . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 1

McFarland - A Snapshot of an Agricultural Community's Health

. . . . . . . . . . . 12

The Child Healthand Disability Prevention Program (CHDP) reaches

less than one-thirdof its target population.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Nutritional programs havefailed to meet the nee&of Valley residents . . . . . . 16

San Joaquin Valley residents rely heavily on Medi-CaI, which does not

guarantee

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .access.

..

18

Community and migrant clinics are underfundeed, do

not existin all

areas of the Valley, and are not available

to all. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

B. SIGNIFICANT BARRIERS IMPEDE ACCESS TO HEALTH CARE . . . . . . . . . .

Bureaucracy thwarts utilizationof programs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Cultural barriers discouragem qfrom seekrng needed care . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Knowledge of available services is often Iackrng . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Overlap, duplication and lack

of coordnation leads to inejficient

use of resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

21

22

23

24

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page vi

Table of Contents

from health care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Provider barriers keep people away

Financial barriersforce many to delay n e c e s s q care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Adequate iramportationis often unavailable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

C. THE CHANGINGHEALTH CARE ENVIRONMENT PRESENTS

CHALLENGES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A resurgence of antMmnigrantpolicies will deny health careto maw . . . . . .

Proposed Medicaid block

grants and Medi-Cal managed care will

further challenge accessfor the poor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Racelethnicity is inexiricably bound to access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

'

29

29

31

36

-

D.SPECIALPOPULATIONS

MIGRANT AND SEASONAL FARMWORKERS

AND SOUTHEAST ASIANS REQUIRE ADDITIONALATTENTION. . . . . 37

Migrant and seasonal fanmuorkers

face additional barriers to health. . . . . . . 3 7

Southeast Asian rejkgees are often left out

of the vstem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

E. ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES ENDANGER PUBLIC HEALTH . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

IV. FINDINGS ON ACCESS AND HEALTH IN THE SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY . . . . . . . 4 5

A. HOW DO THE COUNTIES RATE ON ACCESS TO HEALTH CARE? . . . . . .

Infant Mortality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Cancer death rates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. Incidence of Disease . . . . . . . . . :. . . . . . . . . . . : . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Tuberculosis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.46

46

.47

48

.49

:

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

49

.................

AIDS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Anemia- . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

51

Diabetes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

specialty

Access

(Referral

care

to Sensitive

Diagnoses)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

syphiljs

I'

B. SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY COMMUMTIES: ACCESS AND HEALTH . . . . . . . .

How Do Individual Communities Rank

in Access to Health Care? . . . . . . . . . .

Accessmeasure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Avoidable Hospitalizationand Ambulatory Care Sensitive

Diagnoses @CS) ranlangs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Pregnancy and birth variables . . . !. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Late prenatal care. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ,. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

54

54

55

55

56

57

1.

Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page vii

Table of Contents

Law birth weight

....................................

Births to teens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Health Access Index Ranks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

what are the relationships betweenaccess to health care

and other indicators? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Poverty and Health Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Ethnicity and Health Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Medi-Cal and Health Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Rural Communities andHealth Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Age of Population and Health Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Disease and Health Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Statistical analysis of results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

V.RECOMh4ENDATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1.

1.

c

58

59

61

62

63

64

65

66

68

69

70

71

A. COMMUNITY HEALTH "PROMOTORES" . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

B . HEALTH CROSS-REFERRAL PILOT PROJECT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

74

C. CHILD HEALTH STAKEHOLDERS' CONFERENCE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

75

D . POLICY INITIATIVE ON MEDICAL TRANSPORTATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

E. POLICY AND DATA ADVICE TO COMMUNITY AND PROVIDERS . . . . . . . 76

VI.CONCLUSI0N . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

79

REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . .

81

APPENDICES

s

OCUS

I

t

APPENDIX A .DESCRIPTION OF DATA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

APPENDIX B .DATA FINDINGS ON COMMUNITY HEALTH ACCESS

. . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

C APPENDIX .

...............................

APPENDIX D .DESCRIPTION OF THE SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY COUNTIES . . . . . . . 112

APPENDIX E .SAMPLE COMMUNITY FACT SHEETS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page viii

Table of Contents

.

4.

.

List of Tables

7 Year Losses in Medicaid and Medicare Revenue under Congressional Proposal33

County Cancer Death Rates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . - 4 8

Incidence of Communicable Disease . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Anemia Incidence per 100,000 Children .,: . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 1

Diabetes Hospitalization Rate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Hospital Admissions for Referral Sensitive Diagnoses (REF) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

Ambulatory Care Sensitive (ACS) Hospital Admissionsper 10,000 Population . 56

Percent of Births with Late or No Prenatal Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

Percent of Infants Born withLow Birth Weight (Under 2500 Grams). . . . . . . . 59

Percent of Births to Teens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

Health Access Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

Statistical Correlationof Health Access Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . :. . . . 70

Ambulatory Care Sensitive (ACS) HospitalizationRates per 10,000 . . . . . . . . . 89

Percent of Births with Late or No Prenatal Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

Percent of Infants Born withLow Birth Weight (Under 2500 Grams) . . . . . . . . 91

Percent of Births to Teens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . : . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

Health Access Index Ranks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

Summary of Health Access Data, by Community . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

Infant Mortality (By County) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

County Disease Rates per 100,000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . :. 98

Special SupplementalFood Program for Women, Infantsand Children

(WIC)Rankings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

B-10 FoodStampUtilization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

B-11 San Joaquin Valley Schools Without School Breakfast . . . . . . . . . . . 1.;. . . . . 101

104

B-12 Medi-Cal Payment for Births 1993 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

105

B-13 CommunityClinicEncounters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Summary

of

Demographic

Data,

by

Community

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

106

B-14

108

B- 15 ZipCodeClusters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5

Table 6

Table 7

Table 8

Table 9

Table 10

Table 11

Table 12

Table B-1

Table B-2

Table B-3

Table B-4

Table B-5

Table B-6

Table B-7

Table B-8

Table B-9

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

.

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Carein the San JoaquinValley

January 1996

Page ix

Table of Contents

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

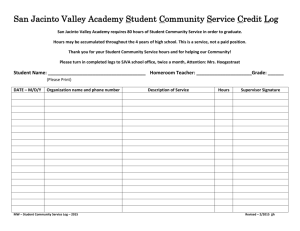

CHDP Utilization in the San Joaquin Valley . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Farmworker Distribution in the San Joaquin Valley, 1991 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Poverty and Health Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Ethnicity and Health Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

Medi-Cal and Health Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

Rural Communities and Health Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

Comparison Between Urban and Rural Communities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

Age of Population and Health Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

Disease and Health Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

i

I

F

if

r

c

Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page xi

Executive Summav

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

California's San Joaquin Valley isone of therichest agriculturalareas in the world. Yet,

the health of its residents who toil inits abundant fields is in a sad state. Farmworkers and the

rural poorare confronted on a daily basiswith a lackof medical providers,inadequate

transportation, and a culturally insensitive health

care system -- problems which undermine efforts

to provide medical care to this population. This report documents the health of San Joaquin

Valley communities,the barriers to care faced by the residents, and the challenges aheadto

ensuring that the underserved and uninsured of theSan Joaquin Valley gain equal

access to health

programs and services.

The material presented here

is the result of a year long investigation

of health conditionsin

the San Joaquin Valleyby the Rural Health Advocacy Institute, ajoint project of California Rural

Legal Assistance (CmA) and CRLAFoundation.

In this report's major parts we:

describe our methodology for evaluating policy issues, analyzing community level

data, conducting an inventoryof health services and convening community

focus

groups.

analyze severalkey impediments to health care, including1) the underutilization

and underlimdingof preventive health programs,2) the cultural, financial,

bureaucratic, transportation, and knowledge barriersto care, and 3) the policy and

structural changes confronting the delivery of health care to the poor and

immigrant residents witha special focus on farmworkers and Southeast Asian

refugees.

present county level healthindicators and comparethe county health access

findings withthe Healthy People 2000 disease prevention and health promotion

goals established by the federal government.

rank the 61 San Joaquin Valley community zip-code

clusters using a Health Access

Index, and describethe demographic characteristicsof these communities basedon

the quality of theiraccess to care.

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page xii

c

Executive Summary

0

providerecommendations for fivecommunity-basedprogramswhichwouldhelp

San JoaquinValley residents help themselves to obtain hller participation in

preventive healthprograms and, in the end, a healthier life.

METHODOLOGY

In an attempt to provide a comprehensivelook at the communities inthe eight countiesof

the San Joaquin Valley,this report combines quantitative community healthdata and qualitative ,

information received&om local focus groups and key informant interviewson health access

issues.

There are two major parts to the analysis. The first part is policy analysisof the major

impediments to health care. The second is a statistical analysis which primarily

uses communitybased, rather than county level data. When community leveldata were not available, countydata

were used. Community baseddata allow us to perform small area analysis, and provideus with

statistically reliable informationin areas small enough to identify differences among communities.

Community based data also allows localitiesto conduct self-assessments, identify their own health

needs, and work together to meet the challenges in breaking down barriersto health care.

County data were analyzed to determine the differences betweenthe counties in relation

to: rates of cancer, tuberculosis,AIDS, anemia, and hospital admissions for diabetes and specialist

sensitive hospitalprocedures (referral sensitive diagnoses), and participation inFood Stamps,

Medi-Cal, the Child Health and Disability PreventionProgram (CHDP), and the Special

Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants and Children(WIC). Comparisons to State data

and federal HealthyPeople Year 2000 Goals are provided when available.

We also ranked the 61 San Joaquin Valley communitieson the basis of a Health Access

Index @AI) developed bythe project. The HAI was obtained by first independently rankingthe

communities for the following four health indicators: 1) ambulatory care sensitive hospital

admissions, and rates of 2) low birth weight, 3) late prenatal care, and3) teen births. The

community rankingsfor each variable were'then averaged to provide an HAI score and a final

rank for each community. The communities were placed infour quartiles, with the top quartile

being those communities withthe best health access, andthe bottom quartile beingthe

communities with the worst access to care. The quartile rankingsfor the 61 communities were

analyzed to determine what differences existed betweenthe quartiles in relation to age, relative

poverty, ethnicity and Medi-Cal utilization of

the population, ruralstatus, and rates of AIDS,

syphilis and tuberculosis.

5

2:

€

c

Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page xiii

Executive Sumrnav

IMPEDIMENTS TOIMPROVING HEALTH CARE IN THE S A N JOAQUIN VALLEY

A numberof critical barriers relateto the overall healthof theunderserved and uninsured

persons livingin the San Joaquin Valley of California. We found a panoplyof health programsin

the San Joaquin Valley,but encountered systemicroadblocks that impede the low income

population from obtaining care from these programs. These impediments include:

Underutilizationandunderfunding of existinghealthprogrums

.

..

.

.

TheChildHealthandDisabilityPrevention Program (CHDP) screens less

than a third ofthe target population of needy children inthe San Joaquin

Valley for medical and dental problems.

WIG is funded to'serve less than half of the eligible population.

60,000 San JoaquinValleychildren are deprived of federallysubsidized

school breakfast becausetheir schools have not implementedthe program.

Medi-Calbenefits are not uniformlydistributedandsome poor,

predominantly rural communities underutilizethe program.

Non-profit andpublichealthcenters, the backbone of the healthdelivery

system inthe poor, rural areas, receive insufficient funding

to serve all who

need their services, andface unprecedented challengesby changes in the

delivery system andby federal fundingcuts.

Barriers to healthprograms whichincludebureaucracy, cultural andlinguistic

issues, inadequate knowledge about services, provider hurdles, financial

roadblocks, and most important,

a lack of reliable transportation.

Anti-immigrant legislation such as Proposition 187 whichseverelyhampers the

work of public health and primarycare providers in assuring a healthy population.

Even with a federal injunction prohibiting enforcement

of Proposition 187, the fear

engendered by its passage has mademany immigrants reluctantto seek health care.

Proposed Congressional legislationto bar all immigrants ffom Medi-Cal, Food

Stamps, SSI, and AFDC andother federally funded health and nutritionprograms

will, if passed, leave manywith no services.

Proposed Medicaid block grunts, if passed, will cost the San Joaquin Valley over

$1.5 billion in anticipated federal revenueto serve low income elderly, disabled,

and families with children.Medi-Cal managed cure, soon to be mandatory in San

Joaquin, Stanislaus, Fresno,Tulare and Kern Counties may improve care,but also

c

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page xiv

6

Executive Summary

poses the risk of underserviceto’low income populations

Other important considerations which relate

to the health of San Joaquin residents include:

.

~

I

.

,

Race and ethnicity, which are important predictors of access to health care in the

San Joaquin Valley. The communities with the poorest access to health care have

almost twice the Latino population thanthose with the best access.

Half of the State’s approximately 800,000migrant andseasonalfarmworkers live

and work in the San Joaquin Valley. They are poorly paid, work in dangerous

conditions, and are exposed to pesticides and other agricultural chemicals. This

population’s access to health care is severely limited.

, .

.

Southeast Asian health accessproblems, such as lack of translation services and

inappropriate care resulting from

poor understanding of cultural differences, areall

important areasof concern.

Environmental issues such as lowqualitydrinkingwater, poor ambient air quality,

heavy reliance on pesticides and agricultural chemicals,

threat of lead poisoningin

the poor housing stock, and sitingof toxic waste dumps and hazardous industries

in low-income, minority areas exacerbate health access problems.

SUMMARY OF DATA ANALYSIS

.

.

Our analysis of over a dozen healthand demographic indicators providesno clear picture

of access to care in the San Joaquin Valley. Overallwe found that the health and delivery systems

within the San Joaquinare as varied as the populations served by that system. Some areas and

populations are well served and enjoy good access and health outcomes, comparable

to California

as a whole.

In other areas, lack of transportation and inadequate delivery systems result in high rates

of disease, poor birth outcomes, poor nutrition and ill health. These areas with the worst access

are poorer, have agreater percent of Latino residents, and rely heavily on Medi-Cal.

We first present our county level findings on infant mortality, cancer deaths,

communicable disease and childhood anemia. We thenreport on our community level findings on

prenatal care, low birthweight, teen births, and avoidable hospitalization admissions. Finally we

rank the San Joaquin Valley communities using

our Health Access Index.

c

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page xv

Executive Summmy

COUNTY FINDINGS

All San Joaquin Valley counties, except Tulare, have infant mortality rates

sign@cantly above the State rate.Kern County andFresno County have the worst

overall infant deathrates in the State, as well as the worst infant death rates for

Latinos. (See Table B-7)

0

The San Joaquin Valley has a lower rate of cancer deaths than the State as a

whole. Of the three easily diagnosable and often curable cancers we examined

breast, cervical and colo-rectal- only cervical cancer deaths exceeded the State

rate. However, the Valley death rates for all three cancers exceedthe Year 2000

Goals. (See Table 2)

0

The Valley tuberculosis rate of 15.8 casesper IO0,OOO population, is belowthe

2000 Goal of no more3.5casesper

Staie rate of16.9, but well above the Year

IO0,OOO. (See Table 3)

0

The rate of svphilis in the San Joaquin Valley (6.5 cases per 100,000) is worse

than the State rate of5.6,but better than the Year

2000 goal of no more thanIO

casesper 100,OOOpopulation. (See Table 3)

0

The San Joaquin Valley counties have someof the lowest rates of AIDS in the

State. (See Table 3)

AN San Joaquin Valley counties exceed the Year2000 childhood anemia goals by

to preventive

three to ten times indicatingpoor nutrition and inadequate access

screeningprograms. All counties exceededthe Year 2000 goals of no more than

3% prevalence for childhood anemia, andfour San Joaquin Valleycounties Wngs,

Madera, Merced, and Tulare) exceeded

the state average of 19.3% for children

under age five. (See Table 4)

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care in the San JoaquinValley

January 1996

Page xvi

c

I

Executive Summcny

COMMUNITY FINDINGS

San Joaquin Valley residents

are hospitalized more often

for ambulatory care

as a whole. There isgreat disparity in

sensitive (ACq conditions than the State

ACS rates throughout the Valley, even within cities. For example, ACS admission

rates are eight times higherin Central Stockton thanin East Stockton. (See Table

B-1)

San Joaquin Valley women

are on& slight&less like& ihan California womenas

a whole to receiveearlyprenatal care. However accessto prenatal care is

extermely limited in some San Joaquin Valley communites. For example, over half

the women in the rural Fresno Countycommunity of Huron received late or no

prenatal care. (See Table B-2)

t

c

Infants bom in the San Joaquin Valley are slightly more like&

to be of low birth

weight than infants born

in the Stateas a whole. Over 1 1% of the 1993 births in

N. Modesto/Salida were low birth weight, compared to a State rate of 6.0 percent.

(See Table B-3).

Births to adolescents (under age18) were higher than the State averagein all San

Joaquin Valley counties, with Kings, Fresno, Madera and

Tulare having rates of

7% or higher. Fresno County communities show nearly a three-fold differencein

rate of births to teens. 8.9% of Hemdofliedale's births are to teen mothers

(nineteen or younger), comparedto 24.8% of W. FresnoBurrel's. (See Table B4)

In the table below, we list those communities that rankedthe highest and lowestin our

Health Access Index which combined rankings

for avoidable hospital admissions, late prenatal

care, low birth weight, andteen births.

c

Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page xvii

Executive Summary

Health Access Index*

Ten Best Communities and Ten Worst Communities

Communities

Best

Worst communities

COllUnWiq

community

l&l&

The Mountains

Madera

Central Stockton

San Joaquin

Frazier Park

Kern

Avenal

Kings

HemdonPinedale

Fresno

S. Stockton/French Camp

San Joaquin

Lodi

san Joaquin

E. Bakersfield/ Lamont

KRn

Buttonwillow/Elk Hills

KRn

W. Fresno/Bmel

Fresno

Clovis I sauger

Fresno

Earlmartmixley

Tulare

North Fresno

Fresno

ChowchiUa

Madera

Mehachapi

KRn

DelanohlcFarland

KRn

Tracy

San Joaquin

KRn

Tulare

Tulare

Reedley/parlia

Fresno

*The Health Access Index

was calculate )y combining the ranks for avoidable

We analyzedthe rankings of all the Valley communitiesto determine key differences

in

their composition and health. When compared againstthose communities withthe best access to

care, we found that the areas with the worst access to care (Le. those in the bottom quartile) were

more likelyto:

0

be poor,

haveahigherpercent of Latino residents,

havea greater percent of Medi-Calrecipients,and

havehigherincidences of AIDS, tuberculosisand syphilis.

The age of the population, as measured by both percent of children and seniors did not

affect the outcomes. Surprisingly, the rural or urban designation of the community also did not

appear to sigruficantly affect access. Infact, the rural communitieswere over represented in the

top quartile of our ranking indicatingbetter access to care.

Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page xviii

Executive Summary

RECOMMENqATIONS

~.

We present here five key recommendationsfor low-cost programs whichare designed to

make better use of existing resources. In an era of fiscal austerity and cutbacks in programs, we

must make optimaluse of existing programs to ensure that they serve those most in need. These

programs are designed to provide local communities with

resources to determine the appropriate

allocation of scarce health funds,target programs to meet their needs, and develop collaborative

regional strategies.

1. Community Health“Promotores”. We recommend a program of biliigual/bicultural

community health“promotores” for each of the San Joaquin Valley countiesto workwith local

community groups and individualson reducing barriersto health care, andpromotion of

preventive programs and healthy behaviors. Specialized community healthworkers for Mixteco

and Southeast Asian immigrants are also critical.

2. Health Care Cross-Referral Pilot Project. We recommend a pilot project which would

establish a systemof cross-referrals to health programsby other government fimdedprograms

with which low-incomepersons come in contact. This program would combat the

underutilization andfragmentation of available health services.

3. Child Health Stakeholders’ Conference. We recommend a summit of the S p Joaquin

Valley stakeholders in child healthto collaborate on strategies for confronting the threats to

children’s health andthe CHDP program. We envikion a conference of medical and dental

providers, public health officials, schools, clients, child development specialistsadvocates

and

to

strategize on methods to improve child health services within existing programs. ’

’

4.’Policy Initiativeon Medical Transportation. ’We recommend a program on

transportation

which would investigate community options for improving transportation services, and research

legal and regulatory requirements for these programs. With the assistance of providers, planners,

local govemrnent, and community healthworkers, the project will study innovative programs,

collaborate to replicate existing programs,A d adapt programs and policy initiativesto benefit

transportation scarce communities.

5. Policy and Data ‘Advice to Community and

Providers. We recommend a program to act as

a resource and clearinghouseto provide community providers, public officials, and local

groups

with statistical data and policy analysison changes and initiatives that are affecting the health of

their communities. With a network of researchers,

community’outreachworkers and policy

analysts working on local, state and national issues, we can provide

an invaluable service in

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care inthe San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page xix

Executive Summary

informing these key stakeholders through electronic communications (HandsNet, fax reports,

etc.), newsletters, forums and conferences. These communications w

l

i keep rural California

communities up-to-date on developments and strategies, and provide a forum

for collaborative

efforts.

CONCLUSIONS

We have learnedthat the San Joaquin Valley is not one homogenous region; thereare

sigruficant variationsin the health of Valley communities. Our findings pointto the need to go

beyond the analysis of regional or even countydata. Only by looking at communities can we

understand what impedimentsto health care exist and howto tear down those barriers. Only by

working with communities canwe devise collaborative strategiesto most effectively use scarce

health care dollarsto make livesbetter for those who toil in the heartland.

Armed with reliable information and knowledge, local communities canwork

collaboratively to provide for a better environmentfor the families who live there. Local

citizenry can educatestate and federal policy makers abouttheir needs, and advocate for policies

that help, and do not harm, them. We have proposed five community based programs which

involve local approachesto what are local problems. Through community involvement with

culturally competent programs,we can provide a healthier life

for everyone in the San Joaquin

Valley.

Agriculture in the San Joaquin Valley isthe envy of the world. Yet, the care of those that

make this industry work- farmworkers and their families- is a national disgrace. We can and

must do better.

. .

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 1

I. Introduction

L INTRODUCTION

The San Joaquin Valleyof California isone of the richest agriculturalareas in the world.

Yet, the health of San Joaquin Valley residents who

toil in the fields is in a sadstate.

Farmworkers and the rural poor are conf+onted on a daily basis with a lack

of medical providers,

inadequate transportation, and a culturally insensitive healthcare system -- problems which

undermine efforts to provide medical care for this population. Thisreport documents the health

of these communities, the barriers to care that they face, andthe challenges aheadto ensuring that

the underserved and uninsuredof the San Joaquin Valley gainequal access to health programs

and services.

Description of the San Joaquin Valley

Nestled between the Sierra Nevada Mountainsto the east, andthe Coastal Range to the

west, the San Joaquin Valley stretches for approximately 275 miles through central California. As

the southern part of the Central Valley,the San JoaquinValley covers 27,500 square miles. With

an estimated populationof 3.1 million persons, the San Joaquin Valleyis comprised of eight

counties (San Joaquin, Stanislaus, Merced, Kings, Madera, Fresno,Tulare and Kern). Its major

cities are Stockton, Modesto, Merced, Madera, Fresno, Visalia, and Bakersfield.

The dominant industry inthe Valley is agriculture and food processing, with

over 250

crops being produced and processed. The San Joaquin

Valley is the most productive agricultural

valley in the nation, ifnot the world. Other major employmentis found in the public sector

(particularly schools and correctional institutions), light manufacturing and health care.

Despite its overall abundance, many more San Joaquin Valley

residents are unemployed

compared to California residents as a whole. For January 1995, the unemployment rate for all

San Joaquin Valley counties exceeded 13%, compared to a State rate of 8.7%.

Demographically, the San Joaquin Valley populationis younger, poorer and more Latino

than California as a whole. The population has:

..

.

20% morechildrenthan the State as a whole (32.2% of population v. 26.8%)

45% more poor peoplethan the State as awhole (18.2% v. 12.5%)

20% more Latinos than the State as awhole (33% ofpopulationv. 27.4%)

Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care

in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 2

I. Introduction

(Detailed information about each ofthe counties is containedin Appendix D.)

Description of this report

The material presented here is

the result of a year long investigation of health conditions

in

the San Joaquin Valley. Its purpose was to. ,

0

conduct a' community'needsassessment,usingcommunitybaseddataandinput

from local residents; providers

ruid community groups;

. .

0

identify those healthissuesof

greatest concern;

0

developprogramsandcollaborativestrategies to enhanceaccessforlow-income

persons in the San Joaquin Valley in an era of diminishing program funds and

increasing

discrimination

immigrants.,

against

, .

This report contains four major parts.

0

In the first section we describe our methodology for analyzingcommunitylevel

data, conducting an inventory

of health services, convening community focus

groups, and evaluating policy issues.

The secondsectionidentifiesandanalyzesseveralkeyissuesincluding,

1) the

underutilization of preventive health programs inthe San Joaquin Valley,2) the

cultural, financial, bureaucratic, transportation, and knowledge barriersto care,

and 3) the policy and structural chahgesconfronting the delivery of healthcare to

poor and immigrant residents with a special focuson farmworkers and Southeast

Asian refugees. We also discuss several environmental issues which affectthe

health care of San Joaquin Valley residents.

0

The third section presents study findings in which we describe and rank the 61 San

Joaquin Valley communities using a Health Access Index. We then describe these

communities and show how communities withbetter access to care differ 6om

those where access measuresare poor. We also provide additionaldata as a

resource for local communities, and when possible, compare

the community

measures withthe Healthy People 2000 Goals. By comparing community health

access measures with HealthyPeople 2000 goals, communities can chart their

Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care &the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 3

I. Introduction

progress in meetingthe “gold standard of disease prevention and health

promotion goals established by the Federal government.

Lastly, in the fourth section we provide recommendations for fivecommunitybased programs which would help San Joaquin Valley residents help themselves

to

obtain hUer participation in preventive health programs and,

in the end, a healthier

life.

Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 5

II. Methodologv

IL METHODOLOGY

In an attempt to provide a comprehensive lookat the eight counties of the San Joaquin

Valley, this report combines policy analysisof structural and political impedimentsto access to

health care confronting the San Joaquin Valleyof California, qualitative information receivedfiom

local focus groups and key informant interviews on health issues, and

quantitative community

health data.

A. EVALUATION OF STRUCTURALAND POLITICAL IMPEDIMENTS TO

IMPROVING ACCESSTO CARE

With the proposed massive federal andstate changes in the health delivery and financing

systems confronting and confounding communities and providers,felt

wethat it was critical to

analyze the impact of these proposed changes on theSan Joaquin Valley'sundersewed

populations. In particular, the analysis discusses Medicaid changes, including Medi-Cal

managed

care, Proposition 187 and other anti-immigrant restrictions, racial disparities ofthe special needs

of farmworkers and Southeast Asian immigrants and key environmental issues.

The ability of

local communitiesto respond to health access barriers is intrinsically linkedto the constant shifts

in health policy, and cogent, timely analysis is necessaryto plan for thefuture.

B. COMMUNITY FOCUS GROUPSAND KEY INFORMANT INTERVIEWS

In order to obtain the full breadth of input on health access issues, we convened local

focus groups. Fourteen focus groups were held in all, two in each county (combining Kings and

Tulare Counties). Over 50 people participated in these focus groups, during June and July 1995,

representing county health departments, community health providers, hospitals, physicians,

nurses, schools, HeadStart, migrant farmworker programs, county government, and community

and ethnic minority advocacy groups. The focus group sessions were composed of three parts: an

explanation of theproject, presentation of local data with a draft community health

fact sheet, and

a discussionof health barriers and localstrategies that have been usedto address those barriers.

These focus groups werereconvened in November and December,

1995 after participants were

presented withan earlier draftof this report. At that time, the groups were able to provide us

with valuable inputon thepreparation of this final report. A list offocus group participants isin

Appendix C.

'Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care inthe San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 6

c

II.Methodology

In addition to the formal focus groups, projectstafF have overthe course of the year

conducted dozens of key informant interviewsof San Joaquin Valley stakeholders involved

in the

delivery of health care. These interviews were designedto obtain more focused information and

to broaden the input of various constituencies such as Southeast

Asian refigees and Mixteco

immigrants. Our project also co-sponsored and participated in regional meetings with the Latino

Coalition for a Healthy California and the

EPSDT Implementation project.

An informal advisory group consisting of experts fiom UCSF Institute for Health Policy

Studies and Primary Care Research Center,the Center for Health Care Rights,Food Policy

Advocates, National HealthLaw Program, Lead Safe California, Center for

Race Poverty and the

Environment and California Rural Legal Assistance were also used

to assist in the design of the

project, provide feedback and review drafts. Additional assistance was obtainedfiom the

Hospital Council of Central and Northern California

and the San Joaquin County Councilof

Governments.

C. COMMUMTY BASED DATA

This analysis primarily uses community-based, rather than county leveldata. When

community level data were not available countydata were used. Community based data allows us

to iden* the characteristics of communities that have certain health problems. In addition, small

area data providethe opportunity to target specific communities with particular health needsto

make cost-effective useof limited resources. These data also allow localities

to conduct selfassessments and compare themselvesto nearby communities, the region and the state. Through

local information, communities can identify their

own health needs andwork together to meet the

challenges in breakingdown barriers to health care.

Data were selected on the basis ofthe following criteria: 1) reliability;2) availability across

the region;' and 3) usefulness and understandability onthe local level.

The variables presentedin this report fall into several broad categories: demographic,

health access, healthstatus, and utilization of existing programs. Many.of the data, such as

poverty levels, birth outcome, prenatal care, teen births, and some disease rates were available

on

Although several counties, suchas San Joaquin, Stanislaus and Merced, have done

health needs assessmentsor data collection, none met the criteria of having uniform data for all

eight counties. We were thus unable to use these reports in the data analysis portion, although

they were extremely usefd in understanding local issues.

c

I

c

Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 7

II. Meihodology

the community level fromthe Census and birth certificates. We were also able

to obtain data on

hospital admissionsfor ambulatory care sensitive diagnoses (ACS)’ on a local level throughthe

University of California at San Francisco Primary

Care Research Center. Other data, including

Child Health and DisabilityProgram (CHDP), Food Stamp and Special Supplemental Food

Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) utilization,

rates of anemia, AIDS,

tuberculosis, andbreast, cervical, and colo-rectal cancer,are presented on a county level either

due to availability or toavoid statistical reliability problems with small

area analysis. In addition,

we were only able to obtain hospital admissionsfor referral sensitive diagnoses (REF)”on a

county basis. Data on transportation were not available. A full explanation of the reported

variables, their relevance andsources can be foundin Appendix A.

1. Small area analvsis

Small area analysis allowsus to reliably report on community conditions and highlight

differences between communities. This is particularly importantin the San Joaquin Valley where

counties are a mixture of large urban centers and isolated rural agricultural communities. The

geographic areas which we chose for this small area analysis are community zipcode clusters,

developed by UCSF PrimaryCare Research Center. These clustersof contiguous zipcodes are

similar to the Medical Service Study Areas

(MSSA) used by the Office of Statewide Health

Planning and Development (Smeloff1981). In total, there are 61 community clusters in the San

Joaquin Valley’s eight counties. (See Table B-15).

,

An advantage of these zip code clusters is that they are large enoughto get reliable

estimates of access indicators, but small enough to capture differences between communities.In

addition zipcode based data are easily assignedto the clusters and local residents more easily

identify their community from among zip

codes. One drawback of zipcode clusters is that zip

c

a

n

’

Ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACS)are “medical conditionsfor which an

admission may be avoidable with timely access

to effective primary care.” (Codman1991). The

rates presented here are for non-elderly adults. The conditions include asthma, chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and

hypertension.

*

** Referral sensitive surgeries(REF) are “high costhigh technology surgical procedures

where impedimentsto access or referral to specialty care may reduce the chances of having the

surgery.” (Codman, 1991). Referral sensitive procedures include hip/joint replacement, coronary

angioplasty and mastectomy.

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 8

II.MethodoloD

codes do not necessarily represent true communities,. and zipcodes change periodically. For this .

reason, we updated the clusters with new zipcodes since 1990 and added newdata. Another

difficulty withthe clusters is that they sometimes include several distinct communities

thus

reducing their utilityfor local analysis. In order to correctly name the zip code cluster using local

terminology, we asked our advisory committee members

for suggestions of names for the

clusters.

2. Health Access Index

’

.

Communities were ranked on the basis of individual variables as well as a composite

“Health Access Index”(€MI)developed by the project. The HAI was obtained by first

independently rankingthe communities forthe following individual variables: ambulatory care

sensitive hospital admissions, andrates of low birth weight,late prenatal care, and teen births.

The communitieswere ranked fromone to 61, withone being the best.and 61 being the worst.

The community rankingsfor each variable werethen averaged to provide an HAI score,

and a final rank for the community. The communities were placed in 4 quartiles, with the top

quartile beingthe best, andthe bottom quartile beingthe worst.

For example, W. FresnoBurrel had the.highest ACSrate in the region and is ranked61

out of 61 on this variable (see Table B-1). This same community had a high

percent of babies

born with low birth weight, andwas ranked 58 (see Table B-3). On the other hand, W.

FresnoBurrel had better than average prenatal care, with a rank

of 26. These, and the rank for

teen birthswere averaged to give a HAI score of 5 1.5 anda final rank of 57.

The quartile rankingsfor the 61communities‘HAI scores were analyzed to determine

what differences existed between

the quartiles in relation to age and relativepoverty of the

population, Latino population, Medi-Cal recipients, ruralstatus, and rates of AIDS, syphilis, and

tuberculosis. Additional analysiswas done through a Spearmanrank correlation coefficient test

to determine the strength and statisticalsigdicance of the correlation betweenthe HAI rank and

the independent variables.

3. Countv Data

Counq data were also analyzed to determine the differences betweenthe counties in

relation to: rates of cancer, tuberculosis,AIDS, anemia, and hospital admissionsfor diabetes and

REF diagnoses, and participationin Food Stamps, Medi-Cal, CHDP, and WIC using methods

..

.

Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 9

II. Methodology

similar to those used for thecommunity rankings. Comparisons to the regional and State data,

and federal HealthyPeople Year 2000 Goals are provided when available.

Detailed tables on these findings are found in AppendixB

4. Data limitations

AU data, including those presented here, havethe&limitations. First, many of the data

were not available on a community level,

so we are limited to presenting them on a county basis.

Second, accurate demographic data on a community levelwere available onlyfrom the 1990

Census. Updated population projectionsare available 6om the California Department of Finance,

but they are limited to counties, cities, andunincorporated areas and do not include such variables

as racdethnicity, income, and language. We were therefore limited in our community analysisto

using 1990 demographic figures, unlessotherwise noted.

The Census has a number of shortcomings, including

its undercount of migrant

farmworkers, homelesspersons and minorities. Also, in a number of instances, using 1990

population figuresas a denominatormay overstate the rate expressed, as the population in most

San Joaquin Valley communitieshas grown since the 1990 Census. For example, when we

present the percent of population on Medi-Cal in a community,we probably overstate it by a

small amount because the actual population islarger than the denominator used. In this instance,

the county data are more accurate.

In addition, wewere unable to obtain reliabledata on primary care providers, since no one

data source adequately accounted for all providers.

D. INVENTORY OF HEALTH PROGRAMS

Using existing data and a project surveyof providers, weattempted to produce a

comprehensive inventoryof health care services and programs. Theseresources include hospitals,

primary care, family planning, public health, and school clinics, referral

sources, special programs

such as health fairs, and mobile clinics. Dueto the plethora of programs and the constant changes

in delivery systems,the list is not all inclusive, but is fairly representativeof therange of

potentially availableservices for low-income residents. This inventory is being reproduced as a

separate document andis available fromthe Rural Health AdvocacyInstitute.

. .

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care in the San JoaquinValley

January 1996

Page 1 1

III. Impediments to Improving Health in the Hemiland

III. IMPEDIMENTS TO IMPROVING HEALTH IN THE HEARTLAND

There are a number of significant structural and political impediments which severely

impact the health care of the underserved and uninsured persons living the

in San Joaquin Valley

of California. These roadblocks include the:

..

..

underutilizationandunderfunding of existinghealthprograms;

barriers to health

services;

anti-immigrant

legislation;

and

Medicaidblock grants andMedi-Calmanagedcare.

Other important consideration which relates

to the health of San Joaquin residents include:

..

the relationship of race to access; and

environmental

health

issues.

In this chapter we evaluate these obstacles, as well as the health concernsof two populations of

special concern - migrant and seasonal farmworkers and Southeast Asian refugees.

A. EXISTING HEALTH PROGRAMS ARE SERIOUSLY UNDERUTILIZEDAND

UNDEREWNDED

Both the focus group comments andthe data demonstrate thatthere are many programs

potentially availableto low-income residentsthat are severely underutilizeddue to lack of

effective outreach or knowledge about the programs and their benefits. These underused

programs, which sometimesfail to reach evenhalf of the target population, include inexpensive

preventive services such as CHDP, WIC, and immunizations. Underfundingfurther limits the

abilities of these programs to meet public health needs.

In this sectionwe review the utilization data on a number of programs and

report on how

these programs are not uniformly availableto all residents of the Valley. In a number of instances,

rural and low-incomeareas are much less likelyto receive the services, despite increased need and

eligibility. Before reviewing these data, it would be usefulto provide a comprehensive lookat

one particular community, McFarland, which recently received much

focus from health authorities

because of a childhood cancer cluster.

.

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 12

III. Impediments to Improving Health in the Heartland

McFarland - A Snapshot of an Agricultural Communiiy's Health

Perhaps the most salient example

of a

San JoaquinValleycommunity'sunderuseofTheKernCountycommunity

of

is the K~~ county

of

McFarland

provides

snapshot

a

of the poor

McFarland. It providesasnapshot of the

healthandunderutilization of healthservices

health of low-income

a

farmworker

in low-income

a

farmworker

community

in

the

community in the richest agricultural Valley in

richest agricultural valley in the world.

the

,

In 1991, the California Department of Health Services issuedits report on the McFarland

Child Health Screening Project. This report on the health of McFarland children is the most

comprehensive evaluationof a San Joaquin Valley population ever undertaken, and is indicative

of

the underutilization of health care in the Valley as a whole. The project was in response

to

community concernsof poor child health andthe cluster of childhood cancersthat had been

identified in McFarland. The report provides a "snapshot" of the health and accessto health care

of a San Joaquin Valley agricultural community. The highlights

of the study, which screened more

than 90% of McFarland's children, are as follows:

6

c

c

Seventy one percent of the children were referred for follow-up care.

Over 36 percent of the children had no evidence of ever having seen a dentist.

22 percent of the childrenwereanemic.

A largerpercent of McFarlandpre-schoolchildrenhadincompleteimmunizations

compared with a sample of California's kindergarten population. This was

especially true for measles, mumps, rubella, and oral polio vaccine.

.. ,

ManyMcFarlandresidentshave dficulty obtainingneededhealthcare.Parents

of

the screened children (especiallythose on Medi-Cal) must travellong distances to

obtain medical care.' Many reported cost, long waiting timesat the doctor's office,

transportation dficulties, lack of child care facilities, and language differences

as

barriers to medical care.

Although the screening foundno additional cases of cancer, it did find massive health and

health access problems. These problems, according to the state's experts, "clearly pointto

McFarland's need for better primary and preventive care services.'' Thereport also found that

c

c

Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 13

III. Impediments to Improving Healthin the Heartland

existing State programs such as WIC, CHOP andthe immunization program, as well asthe

community health clinic, were underutiliied.

The McFarland screeningreport unfortunately validatesour findings that primary and

preventive care services are severely underutilized in poor, rural, farmworker communities, with a

detrimental health effect on children and families.

The Child Health and

Disabiliv Prevention Program (CHDP) reachesless than onethird of its targetpopulation.

The Child Health and Disabilities

PreventionProgram (CHDP) is one of the mostTheChildHealthandDisability

extensive

programs

available

to lowPrevention

Program

(CHDP) screens

less

than

incomechildren,regardlessof source of

athird of the target population of needy

offdy,

or immigration stabs,

children in the San Joaquin Valley for medical

income,

cmp is

ofthe mandatory dental

and

problems.

The

percent

of high-risk

Medicaidcomponentcalled EPSDT (Earlychildrentested

for leadpoisoningwasalso

- below 10% in all counties.

and PeriodicScreeningDiagnosis andverylow

Treatment). California meets its federal

Medicaid requirementthrough its countybased CHDP programs, which also uses tobaccotax money to provide health screens and limited

treatment for non-Medi-Cal eligible low-income children. Despite broad mandates, in 1993-94

CHDP provided preventive health assessments

to less than a thirdof its target population in the

San Joaquin Valley. Utilization variesfrom a high of 32% of children served in San Joaquin and

Fresno Countiesto a low of 23% in Stanislaus County (see Figure 1.) Although the Valley

screening rates were somewhat better than the State, they are stilltoo low to adequately serve the

needy population.

we

“Manyparents who are refmed to the labfor their children’s bloodlead tests are charged

$15for the test eventhough they are not supposedto be. This may be why they are not

going to the lab. ” Mixtecofarmworker representative in Madera

Dental and lead poisoning screening for children had similarlow utilization patterns. The

percent of high-risk children testedfor lead poisoningwas below 10% in all counties.

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care inthe San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 14

III. Impediments to Improving Health in the Heartland

,.

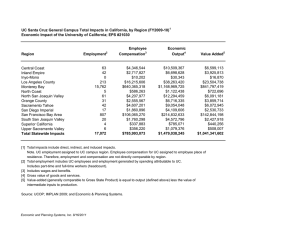

Figure 1

CHDP Utilization in San Joaquin Valley

(Percent of target population receiving services)

~....

Health

assessments

Blood lead

assessments

..

i

40

20

I Fresno 1 Kings (1 Merced I Stanislaus I

State

Kern

Madera San Joaquin Tulare

'

.

.

In discussions with CHDP providers, referral sources and advocateswe learned of many

challenges facing CHDP. First, CHDP isrun as a separate, local programin every countyin

California. While there is a centralized state office that provides oversight, the operations of. .

CHDP differ from countyto county, and communityto community.

"With only one or two public health nurses in the county, they cannot get around to

everyone. We have only seen our CHDP nurse once in the last three years " Rural health

clinic nursepractitMner.

Second, with funding restraints,statsng for public and provider outreach, education and

interventions has been reduced. It is difficult for county CHDP staffto provide the necessary

services withthe minimal staffs allocated to their programs.

Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 15

III. Impediments to Improving Health inthe Heartland

Third, limitedfinding for the

follow-up services andthe lack of providers willing to

accept CHDP children make accessingtreatment services diflicult. Access to dental care is one of

the predominant problemareas cited in most communities, along with very limited mental health

services. Follow-up for those children with high blood lead counts is diflicult. The needfor

follow-up to lead poisoning wouldbe even greater ifthe testing mandates were notroutinely

ignored.

Fourth, providers find it dficult toobtain approvalfor treatment and case management

services identifiedas being necessaryin the CHDP screens. The State Medi-Cal program has only

recently implemented atreatment authorization request process for follow-up services, but

providers are not yet familiarwith the process.

Fifth, lack of transportation makes it difficult for parents to get to appointments. Lack of

child care for siblings is also a problem while at appointments.

Sixth, new policy initiatives suchas Medi-Cal managed care and the Governor’s CalReach

proposal, threaten the viability of CHDP becauseof their differing eligibility and service mandates.

Medi-Cal managed care systems are not yet fullyaware ofthe CHDP scope ofservices mandates.

CalReach proposes to divert finding 6omCHDP into a different program that would not serve

undocumented children. Perhaps the greatest threats to child health programs are thecurrent

congressional proposals to repeal Medicaid and provide smaller block

grants to the States with no

mandatory eligibilityor services.

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care inthe San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 16

III. Impediments to Improving Health in the Heartland

Nutritionalprograms have failed to meet theneeds of Valley residents

In 1991, CRLAF reported the results

of the Community Childhood Hunger

Identification Project (CCHP) survey in its .

nationally acclaimed Hunger in the Heartland

This report showedthat more than one-third

of the families interviewed infour San Joaquin

Valley counties faced severe hunger. Among

those interviewed, 36% reported serious

problems getting enough food; 98% of hungry

families ran out of money for food for an

average of seven days per month, and25%

did so every month. An additional 32% of

families were at risk for hunger. No re-survey

has been funded butthe indications are that

not much has changed,as evidenced bythe

high rates of anemia among childrenhi the

Valley.

'

_ _ _ _ _ ~

~~~

Many low-income families in

the San Joaquin

Valley go hungry:,

WIC is fimded to servelessthan half

of the eligible population.

0

Fifteen percent of the SanJoaquin

Valley residents are on food stamps,

compared to 10% statewide.

0

'

Over 60,000 San

Joaquin

Valley

children are deprived of the federally

subsidizedschoolbreakfastprogram

because theirschools have not

implemented the program.

'>,

0

WIC

~~

Thechildhoodanemia

rates arethree

than

higher

times

to ten

the Year 2000

goals, about the same asthe State rate

of 19.3%.

Special

Supplemental

The

Food

Program for Women, Infants, and Children

(WIC) is a supplemental food and nutrition

education program for low-income pregnant, breast 'feeding and post-parturn women, infants and

children up to the age of five who are at nutritional risk. The purpose of WIC is to prevent poor

birth outcomes and improve healthof participants during critical times

of growth and

development. Local WIC services, provided by public and local non-profit health agencies, are

the gatewayto other health care services. WIC helps ensurethat participants are seen for health

assessments and for ongoing pediatric and obstetric services, suchas prenatal and well baby care,

checkups and immunizations. WIC currently receives funds sufficientto serve less than50% of

the target population.

In its recent WIC 2000 report, the Department of Health Services ranked California

counties by special need for WIC. AU San Joaquin Valley counties rated in

the bottom h a ,

indicating higher risk and special needfor WIC. On a scale of one to eleven, with one beingthe

best, Kern County receiveda rank of 11; Fresno, Madera and San Joaquin10; Tulare 9; Kings 8;

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care in the San JoaquinValley

January 1996

Page 17

III. Impediments to Improving Health in the Heartland

Stanislaus 7, and Merced6 . However, fundsfor all San Joaquin Valley counties were insufficient

to serve evenhalf of potentially eligible women and children: (See Table

B-9).

Among DHS's recommendations for strengthening WIC programs were 1) requiring local

WIC agencies to explore co-locating, out stationingor sub-contracting services withother

agencies who request WIC in their area, particularly Comprehensive Perinatal Service Program

sites, and 2) additional fundingto allow for planning and developmentof collaborative efforts

with other programs, including comprehensive integrationof WIC services with managed care

providers.

The local administrationof WIC allows service providersto target groups most in need.

Often they canwork cooperatively with other agencies. For instance, the United Health Centers

clinic in Parlier has a WIC office on-site which serves

its year round patients,as well as migrant

farmworker families. It also has outreach sitesin small farming communities such asMendota.

The Economic Opportunity Commissionin Fresno also provides WIC services along with

its

other services which include family planning and employment education. However, more needs

to

be done. Many service providers toldus of the failure of WIC programsto coordinate services

with other providers of prenatal care such as CPSP. In addition, increased funding would allow

service to more of the intended beneficiaries.

Food stamDs

Although food stamps supplement the incomes

of many in the San Joaquin Valley, large

numbers of families still go hungry because of the low amount of food stamps they receive. Far

more San Joaquin Valley residents rely

on food stamps than familiesin the State as a whole.

Fifteen percent of the region's households are on food stamps, comparedto 10% statewide. The

county rates range from a highof 20% of Merced County to a low of 12% of Stanislaus families.

(See Table B-10).

School breakfastprogram

The useof federally h d e d low-cost school breakfast funds alsofalls short in the Valley.

Over 60,000 children were in schools with low-income enrollment exceeding

30% which did not

have school breakfast programs but qualifiedfor special federal subsidies. In Kern County alone,

there were over20,000 children deprived of essential nutrition in a program that

costs the local

districts littleor nothing and can help prevent malnutrition and anemia, raise school attendance

and aptitude scores. (See Table B-11).

.

-

’ Hurting in the Heartland: Access to Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 18

III. Impediments to Improving Health in the Heartland

Recent successesin Fresno and other counties have resulted in increased school.breakfast

programs due to community collaboration andefforts to educate local districts and communities

on the benefits and availabilityof the school breakfast program.

.

.

..

San Joaquin Valleyresidents,relyheavily on Medi-Cal, which

does not guar&tee access.

I ,

Medi-Cal benefits are.not uniformly

distributed in the Valley and some poor,

predominantly

communities

rural,than

underutilize the program.

,

’,

SanJoaquinValleyresidents

were . .

.50% more likely to be on Medi-Cal ,.

the statewide

population.

’

I

’

Medi-Cal paid for over’60% ofbirths

in the San Joaquin Valleyin 1993

compared to 48% statewide. It also

paid for 55% of prenatal care,

,compared to 46%

statewide.

.,

Medi-Cal utilization can be viewed

.

several ways. High Medi-Cal utilization can

r

be used as a proxy for the high poverty rate

of an

area. It can

‘also

be

used

to . .

’

demonstrate the lack

relative

of mainstream

.. .

providers who generallyshunimpoverished . . 0

Medi-Calbenefits are notuniformly

distributed in the Valley

and some

:

communities

of the Valley due to poor

reimbursement

professional

and isolation.

poor,

predominantly

rural,

On the other hand, high Medi-Calutilizationcommunitiesunderutilize

the program.

can also be viewedas a community’s success

in accessing a programthat provides health

benefits through a combination of public and private providers. For those low-income families

that are eligible, Medi-Cal paysfor a.fUll rangeof primary, acute.care and long term care services

including prenatal care, prescription drugs, servicesfor the disabled, nursing home care, and

hospital care. Undocumented immigrants, if otherwise eligible, receive only emergency and

’

pregnancy related benefits. Clearlythe 50% of the poor who are on Medi-Cal are better off than

the other half of the poor who are uninsured. However Medi-Cal coverage is no guarantee of

services sincethere are relatively few providerswho accept Medi-Cal due to low reimbursement

rates, red tape, limited rangeof services and perceptions aboutthe Medi-Cal population.

I

.

’

“Less than half of card carrying Medi-Cal recipients actual& use it And that’s a real

problem They don’t use,it.” Lntino activist in Sun Joaquin County. ’

. . ... .

,

San Joaquin Valley residents rely heavily

on the joint federal-state government Medi-Cal

program. Overall, San Joaquin Valley residents were50% more likely io be on Medi-Cal than :

the statewide population.Over three-quartersof a million (756,140), or one out of four (24.2%)

Hurting in the Heartland: Accessto Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley

January 1996

Page 19

III. Impediments to Improving Health in the Heartland

San Joaquin Valley residentswere on Medi-Cal in September 1994, including 442,957 children

In contrast, only approximatelyone out of six of all Californians (16.6%) received Medi-Cal at

that time.

Medi-Cal paid for over 60% of births in the San Joaquin Valley in1993 compared to 48%

statewide. It also paid for 55% or prenatal care, comparedto 46% statewide. (See Table B-12).

Participation in Medi-Cal is not uniformly distributed among low income communities.

Some very low income communities, suchas Huron, CoalingaMendota and Corcoran, use Medical much less than other more affluent communities.

Community andmigrant clinics are

unakrfinded do not exist inall areas

of the Valley? and are not

available to