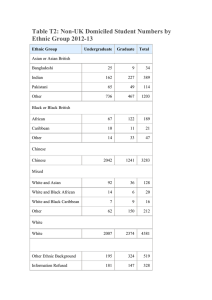

Access of ethnic minorities to higher education in Britain:

advertisement