The Principling Role of Korean in Phonological Adaptation

advertisement

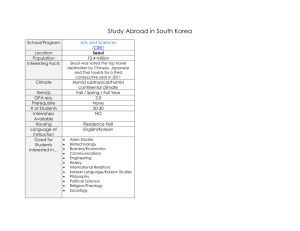

The Principling Role of Korean in Phonological Adaptation 30th Anniversary Meeting of the International Circle of Korean Linguistics Seoul National University, October 22, 2005 Gregory K. Iverson University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee iverson@uwm.edu 1. Introduction. The study of loanword phonology has experienced a sharp resurgence in recent years, motivated by a theoretical interest in the idea that the ways that borrowers adapt the pronunciation of foreign words can shed light on phonological principles governing the language of the borrower — principles that otherwise might not be open to observation. Researchers have generally been following two, largely independent avenues of approach. On the one hand is the tradition of CATEGORY PRESERVATION & PROXIMITY (or “Phonemic Approximation”), pursued especially in the work of Darlene LaCharité and Carole Paradis (e.g., Paradis & LaCharité 1997, LaCharité & Paradis 2002, 2005). The essence of this view is that loanword adaptation is based chiefly on the perception by bilingual adapters of contrastive categories in the source language as these are made to conform to the structural requirements of the recipient language. On the other hand rests the model of PERCEPTUAL ASSIMILATION (or “Phonetic Approximation”), which has been given prominence in the psycholinguistic experimental work of Sharon Peperkamp and Emmanuel Dupoux (e.g., Dupoux et al. 1999, Peperkamp & Dupoux 2003, Peperkamp 2005). This approach claims that loanword adaptations are phonetically minimal modifications, or transformations, that apply “…during speech perception: the process of phonetic decoding maps nonnative forms onto forms that are in accordance with the native phonology. This process is thus influenced by but not identical to the phonology of the listener’s native language.” (Peperkamp 2005:9). The Perceptual Assimilation model, in short, sees loanword adaptation through the lens of the phonological system of the recipient language, whereas the Category Preservation model attributes the nature and directionality of adaptations to listeners’ awareness of the phonology of the source language. In this paper, I will highlight certain aspects of loanword adaptation in Korean that I believe confirm the general thrust of the Perceptual Assimilation model, underscoring that it is indeed the phonological categories of the recipient language rather than the source which are determinative. I am honored to be in Seoul to bring these points before the 30th anniversary meeting of the International Circle of Korean Linguistics, and wish to express my appreciation to former President Sang-Oak Lee for arranging and organizing this commemorative event, revealing again his characteristic skillfulness, professionalism and dedication to the work of the Circle. I am also very pleased to be joined today by many fine colleagues, from distinguished pioneers in Korean linguistics 2 — previous Presidents Chin-Wu Kim and Byung-Soo Park — to current collaborators, former students and many enduring friends. None of these is responsible for the perhaps odd title I have given for this talk, however: “The Principling Role of Korean in Phonological Adaptation”. With the adjective principling, the seldom heard present participle counterpart to principled,1 I had in mind just to showcase how Korean phonology is again figuring in prominently to major theoretical issues of the day. I did something like this before in a different venue and on different issues (Iverson 2002), but it bears repeating today that the sound system of Korean is pivotal in helping to establish what the principles are that govern the phonologies of languages in general. 2. The influence of orthography. The Perceptual Assimilation approach has roots in the psycholinguistic work of Catherine Best and her colleagues (e.g., Best & Strange 1992; Best, McRoberts & Goodell 2001), which in fact coined the acronym PAM, for Perceptual Assimilation Model. Applied to loanword phonology, this general approach is both straightforward and successful: minimal modifications are made to source language forms to bring them into conformity with the pronunciation requirements of the recipient language. For example, the word banana has been introduced in many languages (a 16th century loan presumably from Portuguese or Spanish via Mande [West African]), but it always comes out something like [bənænə] or [banana], never [pʰɪkəl] or [kʰjukəmbɚ]. (1) banana → [b̥ənænə] (English), [banana] (Japanese); *[pʰɪkəl], *[kʰjukəmbɚ] [panana], alternating with [p’anana] (Korean); *[pənɛnə], *[p’ənɛnə] The hypothesis of ‘mimimal modification’ in the phonetic adaptation of loanwords is thus widely supported, perhaps trivially so, but, as always, the interesting cases revolve around departures from predicted results. Pronounced as [panana], the word banana in Korean today seems unremarkable inasmuch as its initial stop, lax [p], is the phonetically closest approximation that Korean has to an initial lenis bilabial stop such as occurs in English (Iverson & Lee 2004). If the word first came into Korean directly from Portuguese or Spanish [banana], on the other hand, or even indirectly via Japanese [banana], its alternate (and presumably older) Koreanization as [p’anana] with an initial tense stop and the vowel [a] throughout would also constitute a minimal departure from the source pronunciation in view of the substitutions that Korean phonology imposes. It would not be expected by the measure of minimal modification, however, that the pronunciation [panana] could be a borrowing from English [b̥ənænə], because Korean does have vowel phonemes close to English [ə] and [æ] — if English were the source, As my colleague Joe Salmons points out, the word principling is recognized in the Oxford English Dictionary Online as having been in existence since 1649, with the meaning, “To be the principle, source, or basis of; to give rise to, originate.” 1 3 the word in Korean should be [pənɛnə], since this is the closest Korean phonetic and phonemic approximation to English [b̥̥ənænə]. If English nonetheless is the source, on the other hand, then presumably it would be Korean awareness of the English spelling of the word with the letter a throughout that determines the vowels in the Korean renditions. I suppose that banana has been a word of Korean for longer than the language has been susceptible to the influences of English. But there are other words of clearly English origin whose vowels can be explained only as a spelling pronunciation of the English orthographic representation. An interesting instance of this effect that was recently brought to my attention is the Koreanized form of the word coffee [kʰɔfi]. Korean has no /f/ phoneme, of course, for which it regularly substitutes native aspirated /pʰ/, so the modern pronunciation [kʰəpʰi] is the phonetically closest approximation. But an earlier form of the word, now out of fashion, is [kʰopʰi], with the vowel [o] conforming to the English spelling of the word with the letter o. I am informed that [kʰopʰi] is also the spelling-influenced pronunciation of an earlier Korean form of English copy [kʰapi], now rendered truer to the source pronunciation as [kʰapʰi]. (2) coffee [kʰɔfi] → copy [kʰapi] → lobby [labi] → radio [ɹeɪdio] → Swordfish [sɔɹdfɪʃ] [kʰopʰi] → [kʰəpʰi] [kʰopʰi] → [kʰapʰi] [ɾobi] (*[ɾabi]) [ɾadio] (*[ɾɛidio]) → [sɨwədɨpʰiʃwi] (*[sədɨpʰiʃwi], *[sodɨpʰiʃwi]) Similarly, the word lobby [labi] has been Koreanized with [o], as [ɾobi], even though the equally possible *[ɾabi] would be a phonetically closer approximation, whereas radio [ɹeɪdio] comes in as [ɾadio] (the variant [nadio] with initial [n] is now antiquated) rather than the closer possibility, *[ɾɛɪdio]. Equally if not more telling of spelling influence, and more recent, is the John Travolta film title Swordfish [sɔɹdfɪʃ] rendered as [sɨwədɨpʰiʃwi], with phonetic expression given to the “silent” w of orthographic Sword, i.e., a letter in the source spelling which is not pronounced at all.2 3. English fortis stops in Korean. These and many other examples show that the spelling of English vowels (and even silent letters) rather than native phonemic status plays a key role in how they are adapted into Korean. The extent and domain of orthographic influence on loanword adaptation will doubtless be difficult to delimit generally, though suggestive experiments have been designed by Vendelin & Peperkamp (2005) with respect to English loanwords in French. But it seems clear that, especially with vowels, Korean adaptations from English are influenced by knowledge 2 For these and other Korean examples, I am indebted to Ahrong Lee and Younghyon Heo. 4 of their native spellings. The role of source spelling has also been identified in Korean consonantal adaptations, moreover, notably in the work of Hyunsook Kang (2003), Mira Oh (2004), Younghyon Heo & Ahrong Lee (2005), and Shinsook Lee (2005). One case in Korean that seems amenable to explanation via orthographic influence, but which has been interpreted instead according to the Category Preservation model, concerns the rendering of English voiceless or fortis stops spelled p, t, c/k. As is widely known, these stops in English are generally heavily aspirated, and thus match up well phonetically with (and are adapted as) the aspirated series of stops in Korean. Iverson & Lee (2004) illustrate some substitutions for English aspirated stops in word-initial environments, where the extent of source language aspiration is at its peak; attention can also be drawn in the adaptations in (3) to the obviously spelling-based rendition of the vowels: (3) panorama [pʰænəɹæmə] → [pʰanoɾama] tennis [tʰɛnəs] → [tʰɛnis’ɨ] camera [kʰæməɹə] → [kʰamɛɾa] Surprisingly, however, even voiceless stops that are unaspirated in English are rendered in Korean as aspirated if they are spelled with p, t, c/k in English, such as the medials in: (4) pickle potato happy [pʰɪkəl] → [pʰikʰɨl] (*[pʰik’ɨl]) [pʰətʰeɪɾo] → [pʰotʰɛitʰo] (*[pʰotʰɛit’o]) [hæpi] → [hɛpʰi] (*[hɛp’i]) The Perceptual Assimilation model would suggest that phonetically unaspirated voiceless medial stops in English should correspond to the tense series of stops in Korean (which are phonologically geminate, per Ahn & Iverson 2004), because these are similarly voiceless and unaspirated; but this is not the case: English orthographic p, t, c/k correspond to Korean aspirated stops irrespective of source language aspiration. This is generally true of the voiceless unaspirated stops that are sourced in s-clusters as well, as pointed out by Mira Oh (1996): (5) stick stop spoon sponge [stɪk] → [stap] → [spun] → [spʌnǰ] → [sɨtʰik] [sɨtʰop] [sɨpʰun] [sɨpʰonǰi] (*[sɨt’ik]) (*[sɨt’op]) (*[sɨp’un]) (*[sɨp’onǰi]) school [skul] → [sɨkʰul] (*[sɨk’ul]) skate [skeɪt] → [sɨkʰɛitʰɨ] (*[sɨk’ɛitʰɨ]) 5 The Category Preservation approach to loanword adaptation, by contrast, would hold that the reason these stops from English, though unaspirated, are nonetheless categorized as aspirates in Korean is that listeners are aware that word-internal voiceless unaspirated stops are actually allophones of the English aspirated phonemes. This view claims then that adaptation of the English sounds is based phonologically on English phonemes, not phonetically on English allophones. There is an alternative explanation for these apparent counterexamples to the Phonetic Approximation hypothesis, however, and that is that educated Koreans, who have good knowledge of English spelling conventions, recognize the phonemic correlates in Korean of graphemic p, t, c/k in English. This is a claim then that, rather than processing English sounds according to English phonology, Koreans understand that orthographic p, t, c/k in English — when pronounced at all (psycho has no [p] either in English [saɪko] or Korean [s’aikʰo]) — should correspond to Korean aspirated stops irrespective of their degree of aspiration in English. The orthographic influence hypothesis thus yields the same results for the adaptations in (3), (4) and (5) as the Category Preservation model, but other factors suggest that it is in fact orthographic awareness, not preservation of source language categories, that is responsible for the observed substitutions. First, the adapted vowel in words like stop [sɨtʰop] and sponge [sɨpʰonǰi] does not reflect the phonemic categories of the source, but rather spellings with the letter o, whose phonemic value in English is variable (e.g., /a/ in stop, /ʌ/ in sponge). Interestingly, the vowels of spoon and school, both rendered in Korean with /u/, are also spelled with the letter o, but here it is doubled, indicating awareness on the part of adapters that English orthographic oo corresponds to phonemic /u/. It thus seems clear that awareness of vowel spelling affects the adaptation of these words into Korean, a circumstance which suggests that the spelling of consonants in the source language can be a determining influence as well. Second, when orthography is known to play much less of a role, if any, the prediction of the Perceptual Assimilation/Phonetic Approximation model seems to be born out, with English unaspirated cluster stops matching up with Korean tense (unaspirated) stops, not aspirated ones. This is a matter calling for further research, of course, but some of my Korean consultants, when confronted with oral nonsense forms having initial s+stop clusters like [stin] or [spo], give Korean pronunciations for them with unaspirated tense stops: [sɨt’in], [sɨp’o]. By way of another anecdote, a Korean M.A. degree student of mine — also a high school teacher of English in Korea — recently made a substitution of this sort in explaining how Korean vowel epenthesis works in answer to a question during her final oral examination. The word she chose to illustrate epenthesis with was English stop [stap], with the vowel [ɨ] being introduced to break up the initial [st] cluster; but the spontaneous pronunciation she gave was with 6 unaspirated tense [t’], not aspirated [tʰ], and with the source language-like vowel [a] rather than spelling-influenced [o]: [sɨt’ap]. (6) NONCE WORDS: [stin] → [sɨt’in], not [sɨtʰin]; [spo] → [sɨp’o], not [sɨpʰo] SPONTANEOUS: [stap] → [sɨt’ap] rather than ‘standard’ [sɨtʰop] for stop When asked about these deviations from the ‘correct’ adaptation as [sɨtʰop], she remarked that that pronunciation reflects how the word should be written in Korean, whose rigorously phonemic writing system in turn influences the standard pronunciation. But on the fly, and under the stresses of an oral examination, she gave the pronunciation which the Perceptual Assimilation model predicts when orthography appears not to be an influence. A similar finding emerges in the work on American English flaps carried out by Eun-kyung Sung (2003). Koreans regularly adapt the medial flap in words like potato as aspirated [tʰ] even though, phonetically, it is obviously closest to the native Korean flap sound [ɾ] that is an expression of the liquid phoneme in the language. But no one in Korean pronounces potato as [pʰotʰɛiɾo]. Yet when the influence of spelling is removed, as in Sung’s careful perception experiments, Korean speakers are revealed to perceive American English flaps also as Korean flaps, i.e., as a liquid rather than a stop, just as would be expected under the phonetic approximation model of Perceptual Assimilation. The role of orthographic awareness, in other words, is key in distinguishing the cases that conform to from those that conflict with the predictions of the Perceptual Assimilation model of loanword adaptation. 4. English lenis stops in Spanish. Advocates of Category Preservation nonetheless dispute this conclusion. In their description of the adaptation of English stops by speakers of Mexican Spanish, for example, LaCharité & Paradis (2005) observe that the so-called voiced stops of English, at least in initial position, are phonetically closest to (if not indistinguishable from) the voiceless stops of Spanish. In terms of Voice Onset Time (VOT) values relative to closure release, they report as follows: (7) VOT correlates of stops in Spanish vs. English (LaCharité & Paradis 2005) Phonetic Implementation Phonological value voiced /b, d, g/ voiceless /p, t, k/ SPANISH ENGLISH -VOT (-40 to 0 msec) +VOT (0 to 30 msec) +VOT (0 to 30 msec) +VOT (> 50 msec) 7 The familiar distinction between the articulation of otherwise similar stops in Romance languages like Spanish and Germanic languages like English is thus that the voiceless stops of Spanish are laryngeally the same as the so-called voiced stops of English: both have very short lag VOT, i.e., they are voiceless and unaspirated. As in Korean, these stops are subject to “passive” voicing in voice-friendly contexts, such as medial in the word or phrase, but initially the so-called voiced stops of English are generally as voiceless as the voiceless unaspirated stops of Spanish. Recognition of this identity has led to a new tradition in laryngeal phonology, one that juxtaposes “voice” languages like Spanish or Japanese (with thoroughly voiced ‘voiced’ stops but unaspirated voiceless stop phonemes) to “aspiration” languages like English or Korean (with voiceless unaspirated ‘voiced’ stops initially but heavily aspirated voiceless stop phonemes). This distinction and its implications for cross-language perception have been noted before, as, for example, in description of another English-like aspiration language, Persian: (8) ...Persians are apt to identify foreign voiceless consonants pronounced without aspiration (of the Slavic of Romance type) with their native voiced rather than voiceless consonants, for which aspiration becomes the distinctive feature. This resembles the situation of Englishmen who interpret voiceless consonants in French in a similar way.” (Pisowicz 1987:237) Cued by the ground-breaking phonetic work of Chin-Wu Kim nearly forty years ago, Iverson & Salmons (1995, 2003) (see also Iverson & Ahn 2004) developed what has come to be called the Multiple Feature Hypothesis (or, sometimes, just Laryngeal Realism) in order to distinguish these two language types structurally. Further tested in first language acquisition by Kager et al. (2005) and in historical linguistics by Honeybone (2005), the idea behind Laryngeal Realism is that the thoroughly voiced stops of Spanish should be represented phonologically with the (privative) feature [voice], leaving the voiceless unaspirated stops in the language laryngeally unmarked, or neutral. By contrast, the phonemically voiceless, typically aspirated stops of English are marked with the feature [spread glottis], leaving the so-called voiced stops in this language unmarked or neutral. As the VOT data in (7) reveal, moreover, the voiceless unaspirated stops of Spanish are laryngeally the same as the so-called voiced stops of English, which in initial position are usually voiceless and unaspirated, too. To symbolize these both simply as /p, t, k/ might lead to misidentification in that the established phonographemic practice is for English to use the same letters (b, d, g) for initial voiceless unaspirated stops that Spanish uses for voiced stops, and another set of letters (p, t, c/k) for aspirated stops that Spanish uses for voiceless unaspirated stops. In order to avoid possible confusion over the values of the phonemic symbols /p, t, k/, Honeybone (2005) suggests that the phonetically voiceless unaspirated phonemes of 8 both languages be marked with a diacritic indicating that, despite the spellings (b, d, g in English, p, t, c/k in Spanish), these sounds are really neither voiced nor aspirated: /p∘, t∘, k∘/. Here, however, voiceless unaspirated stop phonemes will be represented using either the symbols /p, t, k/ (reminiscent of orthographic p, t, k in Spanish) or those for “devoiced stops”, /b̥, d̥, g̥/ (reminiscent of orthographic b, d, g in English). The explicit understanding then is that there is no structural difference between these, so that voiceless unaspirated stops in the two languages may be transcribed either as [p, t, k] or [b̥, d̥, g̥], reflecting their differing phonographemic traditions. Still, the articulation of initial neutral stops in aspiration languages may cluster more at one end or the other of the range of VOT variation noted in phonetic implementation, which is observed to run from zero to around 30 msec for the neutral stops. If the English initial neutral stops often fall closer to the lower end of this variation than do those in Spanish, then this slight difference is accurately reflected in symbolizing the “more nearly voiced” English-type stops with [b̥, d̥, g̥], the “more nearly aspirated” Spanish-type stops with [p, t, k]. Indeed, in Korean (another aspiration language), the neutral or lax stops — though fully voiced in intervoiced contexts — are actually lightly aspirated in initial position, falling even beyond the high end of the range of variation for laryngeally neutral stops in English and Spanish (VOT lag for initial lax stops in Korean averages 61 msec, according to the measurements of Silva 1992); thus these are often transcribed as [p‘, t‘, k‘]. The voiceless stops of Japanese are often a bit more aspirated than Spanish voiceless stops, too, but not as much as Korean initial lax stops, and not nearly as much as Korean or English aspirated stops. Phonemically, though, laryngeally neutral stops are structured the same, whether transcribed phonetically along the continuum of VOT variation as [b̥, d̥, g̥], [p, t, k], or [p‘, t‘, k‘]. The phonemic representations for Spanish (or Japanese) [p, t, k] and English [b̥, d̥, g̥] (or even Korean [p‘, t‘, k‘]) then line up as in (9): (9) Laryngeal features of ‘voice’ vs. ‘aspiration’ languages (Iverson & Salmons 1995) Phonemic & Phonetic Categorization Phonological value voiced /b, d, g/ aspirated /pʰ, tʰ, kʰ/ neutral /p, t, k/ ~ /b̥, d̥, g̥/ Voice Languages SPANISH, JAPANESE [voice] [ ] Aspiration Languages ENGLISH, KOREAN [spread glottis] [ ] In view of the phonetic identity between laryngeally neutral stops in Spanish and English, accordingly, it can be expected that Spanish speakers would perceive English neutral “voiced” stops ([b̥, d̥, g̥]) as equivalent to Spanish “voiceless” stops ([p, t, k]) — as indeed they do when they begin to speak English, according to other studies reported 9 on by LaCharité & Paradis (2005). But the authors also point out that, under increased exposure to English, Spanish-speaking learners come to interpret the English neutral stops (written b, d, g) as phonemically voiced in Spanish (also written b, d, g), even though the English ones are phonetically equivalent to the Spanish voiceless stops in terms of VOT relations. LaCharité & Paradis attribute this development to the Spanish speakers’ having applied the presumed voiced-voiceless phonemic distinctions of English, as presented in (7), to the words that they borrow from English. Examples they cite are listed in (10) (with a diacritic ‘∘’ added to the English surface “voiced” stops in order to indicate their actual voicelessness). (10) Voiced stops in English loans in Mexican Spanish (LaCharité & Paradis 2005) ENGLISH SPANISH PHONETIC EQUIVALENT /b/ bar [b̥ɑɹ] [baɾ] *[paɾ] baseball [b̥esb̥ɑl] [besbɔl] *[pespɔl] /d/ dip [d̥ɪp] [dip] *[tip] darling [d̥ɑɹlɪŋ] [daɾlin] *[taɾlin] /g/ golf [g̥ɑlf] [gɔlf] *[kɔlf] gang [g̥æŋ] [gaɲ] *[kaɲ] LaCharité & Paradise emphasize that the prediction of the Perceptual Assimilation or Phonetic Approximation model would be that these words should have been adapted with Spanish voiceless stops, which are phonetically equivalent to the English input stops. The Category Preservation model, by contrast, would offer a structured reason for why these words were rendered instead with Spanish voiced stops: the English stops were interpreted according to their (presumed) voiced phonological status in English, as schematized in (7), not according to their voiceless phonetic reality. If the laryngeal scheme laid out in (8) is correct, however, the Category Preservation claim for these data is simply vacuous because the laryngeally neutral stops of English and Spanish are phonemically as well as phonetically indistinguishable. That is, the initial neutral stops of English (orthographic b, d, g) are represented the same as the initial neutral stops of Spanish (orthographic p, t, c/k) in both the phonetics and the phonology; thus the expected result under either the Category Preservation or the Perceptual Assimilation model is adaptation of phonemically neutral, phonetically voiceless unaspirated stops from English as phonemically neutral, phonetically voiceless unaspirated stops in Spanish. Yet this is not the result which obtains among Mexicans “with increased exposure to English”. 10 (11) Neutral stops in English loans in Mexican Spanish (revision of (10), per (9)) ENGLISH SPANISH PHONETIC/EMIC EQUIVALENT /b̥/ bar [b̥ɑɹ] [baɾ] *[paɾ] baseball [b̥esb̥ɑl] [besbɔl] *[pespɔl] /d̥/ dip [d̥ɪp] [dip] *[tip] darling [d̥ɑɹlɪŋ] [daɾlin] *[taɾlin] /g̥/ golf [g̥ɑlf] [gɔlf] *[kɔlf] gang [g̥æŋ] [gaɲ] *[kaɲ] In short, neither model under consideration accounts for the observed adaptations among these Spanish speakers who have had increased exposure to English. But with that increased exposure comes, it appears, an increased awareness of the graphemic correspondences between the spelling traditions of the two languages — specifically, that the phonemically voiced stops of Spanish line up orthographically with the phonemically neutral ones of English. This represents the learning of a sound/symbol correspondence, however, not a phonetic approximation or a phonemic category preservation. 5. English /s/ in Korean. The adaptation of English /s/ in words that are borrowed into Korean presents another interesting perceptual match-up because Korean contrasts two types of voiceless strident alveolar fricatives: lax [s], which is often described as having a breathy or aspirated quality, as might be represented by [sʰ] (Iverson 1983), and tense [s’], which is produced with the glottal constriction characteristic of the tense series of obstruents in the language (Cho et al. 2002). Either of these fricatives, depending on context, may serve as the rendition of English /s/. Specifically, as Soohee Kim (1999) has shown, English words are borrowed consistently with tense [s’] when the fricative is not in a cluster in the source language, whereas the result generally is lax [s] when the source fricative does form part of a consonant cluster. Some examples she cites are listed in (12) (S. Kim 1999:13). (12) English source words with /s/ (av. 133 ms in clusters, 170 ms elsewhere) a. slump, smog, snack, spar, skate b. test, toast, postcard, disk, mask c. salary man, ceramic, single, size d. gas, bus, peace, news, juice, DOS Adapted Korean fricative Lax Lax Tense Tense [s] [s] [s’] [s’] In experimental work, Soohee Kim found that the duration of English /s/ in a consonant cluster was substantially less than it is when before or after a vowel. Hypothesizing that Koreans are sensitive to this durational difference, she observed that 11 the phonetically shorter fricative (average 133 ms) in English clusters is consistently adapted as lax but the phonetically longer fricative in English singletons (average 170 ms) is adapted as tense. Her studies on the adaptation of English /s/ did not consider Korean tense [s’] to be a phonological geminate, but its period of turbulence or frication generally is longer than that of lax [s] — albeit insignificantly so in initial position, according to Hyunkee Ahn (1999a:69) (199.0 ms for [s’], 194.1 ms for [s]), but significantly so elsewhere, per Kim & Curtis (2002) and Cho et al. (2002). Independently, it has been argued again recently (S.-C. Ahn & Iverson 2004) that Korean phonetically tense consonants indeed do form phonological geminates, based in part on the fact that the closure duration of tense obstruents in Korean overall is considerably longer than that of lax and aspirated ones (for the stops, 207 ms vs. 145 ms and 146 ms, per H. Ahn 1999b:30). This durational difference between lax and tense consonants appears to play a determining role in the adaptation of English /s/: when phonetically shorter, English [s] is perceived in Korean as lax or simplex /s/, but when phonetically longer it is perceived as tense [s’], which phonologically is geminate /ss/. Further support for the key role played by the duration of turbulence in adaptation of English /s/ has been adduced in recent experimental work by Hyunsook Kang (2005). First, manipulating the length of closure durations among medial stops in Korean, Kang found that her subjects perceive Korean stops as either lax or tense depending on how long the closure durations are maintained: (13) Specifically, when the closure durations of tense stops in word-medial, intervocalic positions are shortened, these stops are perceived as lax; conversely, when the closure durations of lax stops in word-medial, intervocalic positions are lengthened, these stops are mostly perceived as tense. (Hyunsook Kang 2005:4) This observation confirms the geminate analysis of Korean tense stops, and, by extension, the tense fricative as well, as length of course is a common (if not the only) expression of geminate status. Kang also found that, inversely co-varying with the length of the consonant, the duration of a preceding vowel affects the identification of the Korean fricative, too, such that a longer vowel results in perception of a lax /s/, whereas a longer duration of turbulence results in perception of a tense or geminate /ss/. As Kang points out, the correlation between vowel brevity and consonant length is familiar from the phonetics of English, a stress-timed language, thus its discovery in stress-neutral Korean was perhaps not expected. Yet when length is realized more in the fricative and less in the vowel, the Korean perception is of a tense fricative, whereas when length is manifested more in the vowel and less in the fricative, the perception is of a lax, simplex fricative. This underscores the direct perceptual association between 12 phonetic duration and phonemic length, with longer periods of turbulence preceded by shorter vocalic intervals triggering the perception of a tense (geminate) fricative. Word-initially, by contrast, consonantal durations are difficult to distinguish, and to measure. In fact, in other languages with initial geminates (cf. Davis 1999), the primary indicator of geminate status is the elevation of pitch in the following vowel, as first reported by Abramson (1992) for Pattani Malay. Apparently, the pressure build-up associated with an increased period of oral constriction results in stiffening of the vocal folds during the articulation of an initial geminate, with the result that the F0, or pitch, in the following vowel is raised. Just this effect has been noted following the tense consonants of Korean, too, as H. Kang (2005) reports and S.-C. Ahn & Iverson (2004) survey. The higher pitch in a vowel following Korean initial tense consonants, where durational differences are less prominent, is thus a natural, expected manifestation of their status as phonological geminates, and indeed seems to be the primary acoustic cue to their identification there (H. Kang 2005). The idea that Korean tense [s’] is phonologically geminate /ss/ is thus broadly supported, and in turn makes understandable the distinctions that Koreans make between two kinds of phonetic [s] in words that are borrowed from English, which has but one kind of /s/ phoneme: phonetically short [s] in English is borrowed as lax /s/ because that fricative is phonemically short in Korean, whereas phonetically long [s] in English is adapted as tense /ss/ because the tense fricative in Korean is phonemically long, i.e., geminate. Like other loanword adapters, then, Koreans process phonetic structures of the source language according to the closest phonemic categories in their native language. One challenge to the view laid out here about the connection between the phonetic duration of the allophones of English /s/ and their phonemic categorization in Korean has been raised by Davis & M. Cho (2005), who maintain that the correlation Soohee Kim observed is not robust. They note specifically that, though English /s/ generally is rendered as lax in Korean when sourced in a cluster, this is not the case with source words containing a final cluster of sonorant consonant plus /s/. In particular, they point out that Kim was troubled by the adaptation of words like [tɛns’ɨ] ‘dance’ or [pʰols’ɨ] ‘false’, which have the tense fricative despite deriving from a cluster in the source language. (14) Korean adaptation of final sonorant plus /s/ clusters a. dance [dæns] → [tɛns’ɨ] (/tɛnssɨ/) b. false [fɔls] → [pʰols’ɨ] (/pʰolssɨ/) Kim did not measure durations in these particular sequences, however, but merely surmised that English /s/ should also be phonetically short in clusters of sonorant consonant+/s/, as it is in clusters of /s/+sonorant consonant or obstruent. But if the 13 duration of English /s/ following a tautosyllabic sonorant consonant is not as abbreviated as it is in other clusters, then /s/ in that context would follow the same general pattern of adaptation that Kim had identified. In fact, in his comprehensive acoustic study of English /s/ over a full range of environments, Klatt (1974) found that /s/ is shorter by 40% in clusters with a following stop (an [s] that Koreans adapt as lax), but shorter by only 15% in clusters with a following sonorant consonant or stop (an [s] which Koreans adapt as tense). In other words, it is not so much that English /s/ is short when in a cluster, but that it is short specifically when it occurs as the first element in the cluster. (15) If [s] is followed by a plosive in a two-element cluster, the [s] duration is shortened to 60% of the value [of prevocalic [s]]. If [s] is preceded by a nasal or plosive, the [s] duration is shortened to 85%. (Klatt 1974:60) Other data show that English /s/ is substantially abbreviated before a tautosyllabic sonorant consonant (as in snap, slip), too, not just before a plosive (spit, step); but the degree of shortening of /s/ following a sonorant consonant (dance, false) or plosive (matrix) is much less. It would appear, then, that Koreans adapt English /s/ following a sonorant consonant as tense [s’] (/ss/) because it is above the threshold of brevity that marks the lax fricative in Korean, and in any case is appreciably longer than English preconsonantal [s], which they adapt as lax. All of these facts and observations support the analysis of the Korean tense fricative phonologically as geminate /ss/, in the manner of S.-C. Ahn & Iverson (2004), and indicate that Korean listeners are attuned to length variations in English fricative articulations even though these are subphonemic in English. As differences in consonantal length are contrastive in Korean, then, at least on this analysis, it is understandable why English allophonic durational differences should be apprehended in the process of loanword adaptation. This perception holds even when the length effects of phonological geminate structure are deflected to another acoustic parameter, as in the realization of initial geminate status chiefly through the raising of fundamental frequency in a following vowel rather than through consonantal duration. Consistent with the Perceptual Assimilation model of loanword adaptation, then, the phonetic structures of the English source language in these cases are interpreted according to the phonemic categories of the Korean recipient language. Still, some evidence suggests that adaptation is based not just on phonetics, but also on awareness of spelling, or, more specifically, awareness of phonographemic correspondences. Koreans appear to “know” that English words spelled with p, t, c/k should correspond to aspirated stops irrespective of the degree of aspiration, if any, of the sounds represented by these letters in English. On occasion, even letters which are spelled but not pronounced in English are nonetheless adapted as if they were 14 pronounced, as in the case of the silent w in Swordfish listed in (2) and repeated now in (16). (16) a. Swordfish [sɔɹdfɪʃ] → [sɨwədɨpʰiʃwi] (*[s’ɨwədɨpʰiʃwi]) b. sword = soared = [sɔɹd] Of special interest in this adaptation is not only the interpolated [w] of [sɨwədɨ] for sword, but also the lax rather than tense fricative at the beginning of the word. As the phonetic input from English is [sɔɹd] (homophonous with soared), one expects the fricative to be adapted as tense (*[s’ɨwədɨ]), parallel to the treatment of other prevocalic instances of /s/ in the source language. Instead, the fricative is adapted as lax as if there really were phonetic expression of the orthographic w in this exceptional English word. Since native speakers of (standard) English do not have [w] in their pronunciation of sword, its appearance in the Korean adaptation must be due to the influence of English spelling; this, in turn, implies that the selection of a lax /s/ rather than tense (geminate) /ss/ in this word cannot have been based on the brevity of the fricative in the source language pronunciation, because the fricative of sword is just as long phonetically as that of soared. Instead, it appears that there is recognition of an English orthographic correspondence with Korean phonological structure: English graphemic sC = Korean phonemic /sVC/, while English sV = Korean /ssV/. (17) Orthographic Correspondence: English graphemic sC = Korean phonemic /sVC/, English sV = Korean /ssV/ The correspondence itself is based on phonetics-to-phonology match-ups elsewhere, as exemplified in (12). Yet it is clear that the Korean adaptation of sword as [sɨwədɨ] is not a direct perception of the English phonetic input [sɔɹd], but rather of the English orthographic representation sword interpreted according to learned patterns of phonographemic correspondence. 6. Conclusion. A fitting conclusion to this discussion on the role that orthographic correspondence may play in loanword phonology resides in two other adaptations in Korean that are mystifying from the point of view of either Category Preservation or Perceptual Assimilation: one is the name of the bakery chain with branches throughout Korea, Paris Baguette, the other is the pronunciation of the English loanword truck. The bakery name is from French, of course, and apparently not mediated by English, as evidenced by the absence of [s] in the pronunciation of Paris (French [paʁi], Korean [pʰaɾi]). But as French is a voice language, like Spanish, one expects the adaptation of the initial voiceless unaspirated stop from the source pronunciation to be to the Korean 15 tense stop, as is usually the case with voiceless unaspirated input stops from the Romance languages (e.g., [k’aɾɨpʰu] ‘Carrefour’ or [t’u] in Tous les Jours, another bakery chain; Iverson & Lee 2004). The Korean rendition of a tense [t’] in Baguette follows this pattern, perhaps buttressed by the French spelling with a double tt, and the two voiced stops in this word are also adapted according to expectation, as lax (with medial /k/ automatically voicing to [g]). But the surprise is the aspirated [pʰ] in Paris, because, in French, the stop in this word (and all others) is unaspirated. The alternate Korean pronunciation of this word, [p’aɾi] (/ppaLi/) with a tense initial, is the expected adaptation, yet this is not the pronunciation found in the name of the bakery chain, Paris Baguette. One suspects the influence of English orthographic correspondence here, too, even though the source is clearly French, probably because English is far and away the dominant donor of loanwords in Korean today. If so, then this is a case in which Korean phonemicization of English orthography is applied even to a non-English word. (18) a. Paris Baguette (French) [paʁi bagɛtə] → [pʰaɾi pagɛt’ɨ] b. truck (English) /tʰɹʌk/: [tʃ̫ɹ̥ʌk] ~ [č̫ɹ̥ʌk] → [čʰuɾək], later [tʰɨɾək] The second case, brought to my attention by Sang-Cheol Ahn, is the introduction of the English word truck into Korean with an initial affricate, as [čʰuɾək]. Though largely out of fashion now, this pronunciation seems to have come into the language during the Korean War era, presumably via oral contact with American soldiers rather than through a written medium. My own pronunciation of this source word (and of others in English with an initial /tʰɹ/ cluster) is very much like that early Korean adaptation, in fact, with fricative release of the initial stop deriving from the turbulent nature of the aspiration as it tightly transitions into the retroflex approximant. In addition, my lips are protruded or rounded for the articulation of the affricate before the following rhotic approximant. Thus, my pronunciation of /tʰɹʌk/ as could just as well be symbolized as [tʃ̫ɹ̥ʌk] or [č̫ɹ̥ʌk], which, under the Perceptual Assimilation model, would account for its phonemicization in Korean with an initial affricate as well as for the labiality of the rounded epenthetic vowel [u] rather than the usual [ɨ]. The form this word takes in Korean today, though, is not [čʰuɾək], but rather [tʰɨɾək], a change in the pronunciation which again points to the role of orthography. Specifically, as discussed above in connection with the words in (5), educated Koreans appear to interpret the English grapheme t as corresponding to the Korean phoneme /tʰ/ across-the-board, irrespective of whether the English pronunciation makes a closer fit phonetically with a different phoneme in Korean; and the default high back unrounded epenthetic vowel is used to break up the cluster of imported consonants here ([ɨ] rather than [u]), there being no rounding discernable in the source spelling of graphemic tr as there is in the source pronunciation of phonemic /tʰɹ/. This duality of influences, phonetic and orthographic, 16 has also been identified in the emergence of several loanword doublets in Japanese, as described by Smith (2005). In general, however, the cases reviewed in this paper fall into place under the Perceptual Assimilation model of loanword adaptation, with source language phonetic structures organizing into the closest recipient language phonemic categories. Deviations from that pathway appear to be controlled by the adapter’s awareness of source language spelling conventions and their correspondences to recipient language phonemes rather than to knowledge of source language phonology per se. Schematically, the two identified influences on loanword adaptation — which often are contradictory — lay out as in the synthesis presented in (19). Together, the varied interpretations of acoustic and graphemic form in the cases discussed here highlight once again the centrality of Korean in deciding leading theoretical issues in the study of sound structure. But just where the boundary falls between sound-based and graphemebased adaptation remains still to be determined, likely on a case-by-case basis. (19) Schematic of Loanword Adaptation Source Language Word ↙ ↘ Acoustic Form Graphemic Form (if heard) (if known) ↓ ↓ Encoding into Recipient Language Phonological Categories ↓ Adapted Loanword 17 References Abramson, Arthur (1992) “Amplitude as a cue to word-initial consonant length: Pattani Malay,” Haskins Laboratories Status Reports on Speech Research SR109/110, 251254. Ahn, Hyunkee. 1999a. “An acoustic investigation of the phonation types of postfricative vowels in Korean,” Harvard Studies in Korean Linguistics 7, ed. by Susumu Kuno et al., Seoul: Hansin Publishing Co., pp. 57-71. Ahn, Hyunkee. 1999b. Post-release phonatory processes in English and Korean: acoustic correlates and implications for Korean phonology. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas at Austin. Ahn, Sang-Cheol & Gregory K. Iverson. 2004. “Dimensions in Korean laryngeal phonology,” Journal of East Asian Linguistics 13.345-379. Best, Catherine T. & Winifred Strange. 1992. “Effects of phonological and phonetic factors on cross-language perception on approximants,” Journal of Phonetics 20.305-330. Best, Catherine T., Gerald W. McRoberts & Elizabeth Goodell. 2001. “Discrimination of non-native consonant contrasts varying in perceptual assimilation to the listener’s native phonological system,” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 109(2).775-794. Cho, Taehong, Sun-Ah Jun & Peter Ladefoged. 2002. “Acoustic and aerodynamic correlates of Korean stops and fricatives,” Journal of Phonetics 30.193-228. Davis, Stuart. 1999. “On the representation of initial geminates,” Linguistic Inquiry 16, 93-104. Davis, Stuart & Mi-Hui Cho. 2005. “Phonetics vs. phonology: English word final /s/ in Korean loanword phonology,” To appear in Lingua. Heo, Younghyon & Ahrong Lee. 2005. “Extraphonological regularities in the Korean adaptation of foreign liquids,” LSO Working Papers in Linguistics 5.80-92 (Linguistic Student Organization, University of Wisconsin–Madison). Honeybone, Patrick. 2005. “Diachronic evidence in segmental phonology: the case of laryngeal specifications,” The Internal Organization of Phonological Segments, ed. by Marc van Oostendorp & Jeroen van de Weijer. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 319-354. Iverson, Gregory K. 1983. “Korean s,” Journal of Phonetics 11.191-200. Iverson, Gregory K. 2002. “Korean as catalyst in modern phonology,” Korean Linguistics 11.53-91. Iverson, Gregory K. & Sang-Cheol Ahn. 2004. “English voicing in Dimensional Theory,” to appear in Phonology of English, ed. by Patrick Honeybone & Philip Carr, a special issue of Language Sciences. 18 Iverson, Gregory K. & Ahrong Lee. 2004/2006. “Perception of contrast in Korean loanword adaptation,” to appear in Korean Linguistics. (Revision of “Perceived syllable structure in the adaptation of loanwords in Korean,” Proceedings of the 2004 Linguistic Society of Korea International Conference [Vol. I: Forum Lectures and Workshops], pp. 117-136. Seoul: Hansin.) Iverson, Gregory K. & Joseph C. Salmons. 1995. “Aspiration and laryngeal representation in Germanic,” Phonology 12.369-396. Iverson, Gregory K. & Joseph C. Salmons. 2003. “Laryngeal enhancement in early Germanic.” Phonology 20.43-74. Kager, René, Suzanne van der Feest, Paula Fikkert, Annemarie Kerkhoff & Tania S. Zamuner. 2005. “Representations of [voice]: evidence from acquisition,” to appear in a volume on Dutch laryngeal representation. Amsterdam and New York: John Benjamins. Kang, Hyunsook. 2003. “Adaptation of English words with liquids into Korean,” Studies in Phonetics, Phonology and Morphology 9.311-325. Kang, Hyunsook. 2005. “Tense/lax distinctions of English [s] by Korean speakers: consonant/vowel ratio as a possible universal cue for consonant distinctions,” manuscript, Hanyang University. Kang, Yoonjung. 2003. “Perceptual similarity in loanword adaptation: English postvocalic word-final stops in Korean,” Phonology 20. 219-273. Kim, Chin-Wu. 1970. “A theory of aspiration,” Phonetica 21.107-116. Kim, Soohee. 1999. Sub-phonemic Duration Difference in English /s/ and Few-to-many Borrowing from English to Korean. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington. Kim, Soohee & Emily Curtis. 2002. “Phonetic duration of English /s/ and its borrowing into Korean,” Japanese/Korean Linguistics 10:406-419. Klatt, Dennis H. 1974. “The duration of [s] in English words,” Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 17.51-63. LaCharité Darlene & Carole Paradis. 2002. “Addressing and disconfirming some predictions of phonetic approximation for loanword adaptation,” Langues et Linguistique 28.71-91. LaCharité, Darlene & Carole Paradis. 2005. “Category preservation and proximity versus phonetic approximation in loanword adaptation,” Linguistic Inquiry 36.223258. Lee, Shinsook. 2005. “Perception and production of consonant clusters by Korean learners of English,” manuscript, Hoseo University. Oh, Mira. 1996. “Linguistic input to loanword phonology,” Studies in Phonetics, Phonology and Morphology 2.117-126. Oh, Mira. 2004. “Phonetic and spelling information in loan adaptation,” Proceedings of the 2004 Linguistic Society of Korea International Conference (Vol. I: Forum Lectures and Workshops), pp. 195-204. Seoul: Hansin Publishing Co. 19 Paradis, Carole & Darlene LaCharité. 1997. “Preservation and minimality in loanword adaptation,” Journal of Linguistics 33.379-430. Peperkamp, Sharon. 2005. “A psycholinguistic theory of loanword adaptations,” to appear in Proceedings of the 30th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. Peperkamp, Sharon & Emmanuel Dupoux. 2003. “Reinterpreting loanword adaptations: the role of perception,” International Congress of Phonetic Sciences 15.367-370. Pisowicz, A. 1987. “Developmental tendencies in the voiced–voiceless opposition of stop consonants (on the basis of data from Persian and Armenian),” Problems of Asian and African Languages, pp. 233-238. Warsaw: Polish Academy of Sciences. Silva, David J. 1992. The Phonetics and Phonology of Stop Lenition in Korean. Ph.D. dissertation, Cornell University. Smith, Jennifer L. 2005. “Loan phonology is not all perception: evidence from Japanese loan doublets,” Japanese/Korean Linguistics 14, ed. by Timothy J. Vance. Stanford:CSLI. Sung, Eun-kyung. 2003. Flaps in American English and Korean: Production and Perception. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Delaware. Vendelin, Inga & Sharon Peperkamp. 2005. “The influence of orthography on loanword adaptations,” to appear in Lingua.