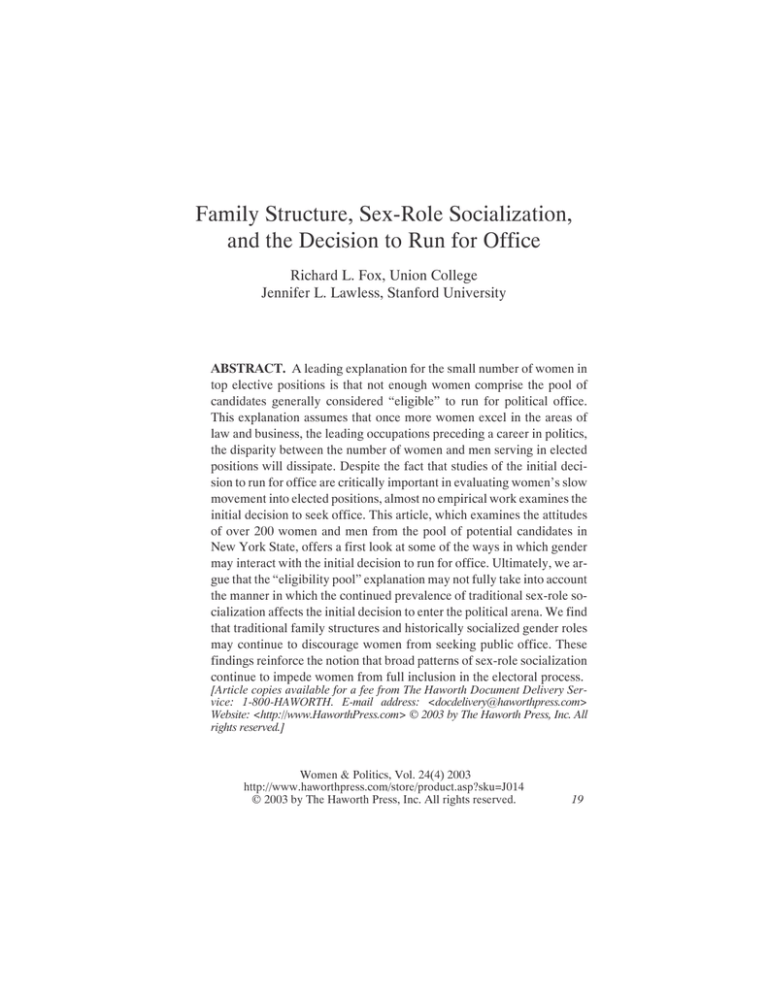

Family Structure, Sex-Role Socialization, and the Decision to Run for Office

advertisement