Doctorate in Educational and Child Psychology Rachel Standen

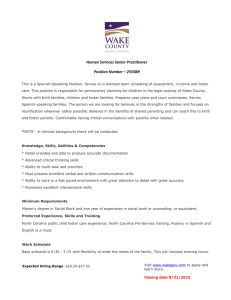

advertisement