Caribbean Creole in Class I. Statement of Purpose

advertisement

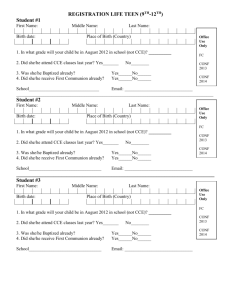

Caribbean Creole in Class Rebecca Karli and Brynna Larsen Structure of English Prof. Baron I. Statement of Purpose As teachers of English Language Learners (ELL) at Roosevelt High School in Washington, DC, our classes are typically composed of native Spanish, Amharic, French, and Chinese speakers. Alongside these English Language Learners, however, are native English speakers who grew up in Caribbean countries such as Trinidad, St. Kitts, Jamaica, and Guyana. Most of these students speak a form of Creole English as their first language. This English emerged historically when African slaves and indentured servants from Asia and Europe were brought together under the control of European plantation owners (Nero, 1997). Curious about the differences between Caribbean Creole English (CCE) and Standard American English (SAE), and concerned about how we could better meet the needs of our Caribbean students, we developed a study centered on four questions: 1) What are the differences between Caribbean Creole English and Standard American English? 2) To what extent do CCE speakers attending U.S. high schools recognize those differences? 3) How are the needs of CCE speaking students different from the needs of non-native English Language Learners? 4) What can teachers of CCE speakers do to better support them? Regarding question one, based on our observations of students at school, we predicted that we would find variance in vocabulary, pronunciation, and grammatical structure. While curious about lexical and phonological differences, we were most concerned with differences in syntax, particularly as they relate to prescriptive grammar. Manipulating sentence structures effectively is central to success in academic writing. Failing to uphold the grammatical Larsen & Karli | 2 structures of Standard American English would present the most academic problems for CCE speaking students in U.S. schools, particularly when it comes to writing. Based on the research of R.B. Le Page (1985) and Kean Gibson (1992), we anticipated that students would confirm differences between SAE and CCE as they relate to markers for tense, subject-verb agreement, plurals, and the present progressive and habitual aspects. Next, we wanted to know to what extent students who speak both CCE and SAE were able to recognize the phonological, lexical and syntactic differences between the two English dialects. For example, would students be aware of the phonological differences between the letters <th> in thing (/θ / in SAE and /t/ in CCE), the letters <th> in that (/ð / in SAE and /d/ in CCE) or the vowel <a> in can’t (/æ/ in SAE and /a/ in CCE)? Would the students be able to provide examples of lexical differences, such as the different meanings of the words hand and foot? While these terms refer to appendages of the arm or leg in SAE, they refer to the entire arm and to the entire leg in CCE. Finally, would students be aware of syntactic differences, such as the need for inflections with plurals, tense, and subject-verb agreement in SAE but not in CCE? Alicia Beckford’s (1999) research on Jamaican Patois speakers suggested that native CCE speakers were most likely to indicate that the difference between CCE and SAE is one of accent and vocabulary only. Only a minority of speakers indicated that the differences were also structural. This, along with the work of Shondel J. Nero (2000), which highlights students’ difficulty identifying the structural differences between the CCE and SAE, led us to believe that the students we interviewed would be unlikely to recognize the structural differences between CCE and SAE, and that they would be more likely to focus on differences in pronunciation and vocabulary. Larsen & Karli | 3 A third focus of our research was to determine how the needs of CCE speakers differ from the needs of English Language Learners. Based on Shondel J. Nero’s (2000) descriptions of CCE speakers’ written work, we anticipated that CCE students would need more explicit instruction in the ways academic writing is distinct from speaking. Compared to ELL students, they would also need more explicit instruction on the structural differences in the use of tense, aspect, and plurals. Arlene Clachar (2006) suggested that CCE speakers will not understand their placements into ELL classes and will gain few benefits of being in these classes. They may find their placement in such classes insulting and unnecessary, thus lacking motivation to recognize the differences between the two dialects and improve their academic writing. We hypothesized that from an academic standpoint our students would also feel insulted about being placed in ELL classes, but that they may welcome this placement from a social standpoint, as they would be surrounded by other recent immigrants. Our final question would focus on how teachers could better serve and support CCE speakers in their classes. The works of Nero (2000), Clachar (2006), and Jeff Siegel (2008), suggest that we look to models such as the Caribbean Academic Program based in Illinois, which uses a well-rounded, scientific, sociohistoric, and humanistic approach to teach differences between SAE and CCE. We hypothesize that teachers are currently doing little of this and that they would benefit from a background in the origins of different English dialects, how they are different, and how to effectively and explicitly teach those differences. II. Research Design Subjects We based our research on 3 high school Caribbean Creole English speakers at Roosevelt High School in Washington, DC, who are current ELL students. While there is a significant Larsen & Karli | 4 population of CCE speakers at Roosevelt, we were not able to get a larger sample because most of them were mainstream students that did not have a relationship with us. The subjects were 3 males between the ages of 15 and18: 2 students from Guyana, and 1 from Trinidad. Two students arrived to the U.S. in middle school and are now 10th graders. One student arrived to the U.S. in high school and is now an 11th grader. All students have a mix of ELL and mainstream classes. We also emailed a teacher survey to 15 ELL and mainstream DC Public School teachers; however, only 8 teachers had experience with CCE students and could complete the survey. Methodology The methodology we used to collect our data was a CCE student interview and a teacher survey emailed to teachers throughout the District of Columbia who have worked with CCE students. The first data collection phase focused on the attitudes and perceptions of CCE speakers and their ability to distinguish differences between SAE and CCE. In the first section, each student was asked about the context where CCE and SAE are used, his attitude and perceptions of CCE and SAE, and his opinion of ELL classes, support, and accommodations at his school. Some examples of our sample questions include: “How would you describe your first language?”, “Do you think students who are from the Caribbean and speak English should be put in ELL classes? Why/Why not?”, and “Are there ways that Roosevelt teachers could better support you?” The second component of the student interview consisted of example problems in three key areas where differences between CCE and SAE were found in the research: pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar/sentence structure. In each area, the student was first asked to produce his own examples of differences and then identify differences in examples that were given to Larsen & Karli | 5 him. Some example problems include: “Pronounce “think” as you would in CCE”, “Are there words that are different in CCE and SAE?”, and “Is the sentence “He rich” okay in CCE? In SAE? If not okay, correct the sentence.” The second data collection phase focused on the attitudes and perceptions of ELL and mainstream teachers who have worked with CCE speakers in the classroom. We emailed a 5 question survey to teachers to determine their attitudes about CCE speakers being placed in ELL classes, their ability to identify differences in CCE English, and to see what strategies they used specifically for CCE students, as opposed to those used for ELL students. A few example survey questions include: “Do you think that Caribbean students should be in ELL to receive training in English? Why/Why not?” and “In which areas do you notice differences in these students' English? (pronunciation, vocab, sentence structure, grammar). Please provide examples.” III. Data Phonological Differences Student 1: Guyana Word SAE 1. my /mai/ /mə/ 1. Hanging 2. she /ʃi/ /ʃɛ/ out 3. the /ðə/ /də/ b. “Bring it 4. where /wɛr/ /wæ/ come” 5. fore- /fɔrhɛd/ /fairhId/ 7. take Guyana SAE CCE 6. man /mæn/ Limin CCE 1. “Can you a. “Carry bring (it)?” come” /man/ /tek/ /tɛk/ SAE CCE 1. three /θri/ /tri/ 2. the / ðə/ /də/ Word CCE Syntactic Differences SAE head Student 2: Lexical Differences SAE I CCE Me SAE 1.“I’m going” CCE “A biliz” Larsen & Karli | 6 Student 3: Trinidad: Word SAE CCE SAE 1. what /wʌt/ /wʌ/ Wa? 2. no /no/ /na/ 3. stupid 1. What’d you say? /stupId/ /strupid/ 4. damn /dæm/ /dɔm/ Limin 5. daughter /dɔtər/ /dɔtɔ/ 2. Hangin ’ out SAE CCE 1. Come here. CCE 1.Come na . Students were asked to identify any specific examples of phonological, lexical, or syntactic differences they were aware of between CCE and SAE. They were given the following list of words to read and their pronunciation is listed below. Deviations from SAE pronunciation are listed in bold. Students’ Pronunciation of Selected Words Word SAE Student Pronunciation Pronunciation thing /θIŋ/ Student 1: /təŋ/ Student 2: /təŋ/ Student 3: /təŋ/ that /ðat/ can’t /kænt/ home /hom/ don’t /dont/ make /mek/ Student 1: /dat/ Student 2: /dat/ Student 3: /dat/ Student 1:/kænt/ Student 2:/kænt/ Student 3: /kyænt/ Student 1: /hom/ Student 2: /hom/ Student 3: /om/ Student 1: /dont/ Student 2: /dont/ Student 3: /don/ Student 1: /mek/ Student 2: /mek/ Student 3: /mək/ Larsen & Karli | 7 body /badi/ you /yu/ father /faðər/ Student 1: /badi/ Student 2: /badi/ Student 3: /bædi/ Student 1: /yu/ Student 2: /yu/ Student 3: /yʌ/ Student 1: /fadər/ Student 2: /fada/ Student 3: /fada/ Students were presented with sentences that use structures that are acceptable in certain forms of CCE, but are unacceptable in prescriptive SAE. Students were not told that each sentence presented one or more problems in SAE. Instead, they were asked to identify if it was acceptable in SAE and, if not, what they would change. Below, we have noted when students were able to correctly identify the problems with the sentences. Student Recognition of SAE Errors Sentence (Issue in SAE) 1. He rich. Confirmed Acceptance in CCE (subject-verb agreement) -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 3 -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 3 3. Yesterday, I wash the clothes. -Student 2 -Student 3 (copular verb) 2. She tell me everything. (past tense) 4. Blake carried guns and threaten other people. nd (2 verb past tense) 5. Students does go on like that. (subject verb/ use of does as habitual) 6. He does go to church every week. (use of does as habitual) -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 3 Correctly Identified the Issue/s in SAE -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 3 -Student 1 Could not Identify the Issue/s in SAE -Student 2 -Student 3 -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 3 -Student 3 -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 1 -Student 2 Larsen & Karli | 8 7. At present, me a du (do) farming. (present progressive: be +ing) 8. Mary a sing now. (present progressive: be +ing) 9. At half-past five me (mi) de a work. (past tense or present progressive: be +ing) 10. My father work two job. (subject verb and plural inflection) -Student 2 -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 3 -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 1 -Student 3 -Student 2 -Student 1 -Student 2 -Student 3 -Student 3 -Student 1 -Student 2 IV. Analysis 1) What are the differences between Caribbean Creole English and Standard American English? The Caribbean Creole English lexicon is largely based on British English, while it draws on West African languages for much of its phonology, morphology and syntax (Nero, 2000). Some Caribbean Creole English, notably Jamaican Creole, also includes words from what is today Ghana, as well as from French, Hindi, Chinese, and American Indian (Le Page, 1985). The types of Caribbean Creole English vary from country to country and also within those countries as related to social class and rural and urban dichotomies (Nero, 2000). Caribbean Creole English speakers speak CCE along a continuum. The acrolect is the form nearest to “Standard English.” The basilect is the opposite, the most “creolized” form. The mesolect exists along the continuum between the basilect and acrolect (Gibson, 1986). While most interested in differences of syntax based on research by Kean Gibson and Robert Le Page, we anticipated that we would also find lexical and phonological variation. CCE and SAE are rooted in British English, and though both dialects show lexical variation from British English, this historical relationship means that while there are lexical differences between Larsen & Karli | 9 SAE and CCE , they are less significant than lexical differences that exist between completely distinct languages. . (Clachar, 2006 Our students confirmed several of the differences For example, each confirmed that hand can indicate the part of the body from the shoulders to the fingers in CCE, that foot can indicate the part of the body from the thigh to the toes, that a next is used instead of another (Nero, 2000), and that they would typically use me as a subject pronoun instead of I in CCE (Le Page, 1985). Two students, one from Trinidad and one from Guyana, described the CCE term “limin” as “hanging out.” One student suggested that this word is used to show a relationship between humans and limes. He said it captures the way limes just “hang out” on lime trees. The students provided few other lexical differences, which supports our understanding of a great lexical overlap between CCE and SAE. Our next focus was on phonological variation and here we anticipated that the CCE speakers would demonstrate deviation from SAE pronunciation of words we provided them. First, we anticipated that the students would pronounce initial consonants differently. For example, thing, which is pronounced /θəŋ/ in SAE, would be /təŋ/ in CCE and that, which is pronounced /ðat/ in SAE, would be/dat/. Similarily, we predicted that can’t, /kænt/ in SAE, would be /kyænt/ and home, /hom/ in SAE, would be /om/. We also anticipated differences in whether or not they would pronounce the final consonant in don’t /dont/ in SAE but /don/ in CCE. Finally, we expected the students to pronounce vowels differently. For example, we thought that students would pronounce you, /yʌ/, in contrast to /yu/ in SAE, make /mək/, instead of /mek/, body /bædy/, instead of /bady/,and father /fada/, not /faðər/ (Nero, 2000). The student from Trinidad showed pronunciation patterns consistent with those described above. However, to our surprise, when we asked our Guyanese students to say each of these words as they would if they were in their native country, they showed little variation from the Larsen & Karli | 10 SAE pronunciation. Initial consonant pronunciation of <th> was consistent with Nero’s description of CCE pronunciation. Both students said /tiŋ/ for thing as opposed to the SAE version /θiŋ/ and they said /dæt/ for that, in contrast to /ðæt/. One of the Guyanese students pronounced father /fada/ as opposed to the SAE form /faðər/. However, for 6 areas in which we expected to find phonological differences, the Guyanese students’ pronunciation was consistent with SAE pronunciation. We believe that the students’ pronunciation is an effect of their time in the U.S. (2.5 years and 3 years) and of their adoption of many SAE pronunciation patterns. Students may also have demonstrated more pronounced CCE pronunciation had we captured natural speech, rather than having them read us words in isolation. The final and most crucial area of examination was the difference in syntax. Here, we expected that our research with CCE speaking students would confirm that in CCE there are no inflections for tense, subject-verb agreement, and plurals. We also expected they would confirm the lack of copular verbs when predicates are adjectives and the unstressed use of the verb does to indicate habitual action (Nero, 2000). We anticipated that our Guyanese students would confirm their use of a + verb and/or a + verb + ing to indicate the present progressive aspect (Gibson, 1992). The students from Guyana confirmed the usage of nearly each of the structures described above in their native dialect. The only discrepancy was over the past tense sentences, “Yesterday, I wash the clothes,” and “At present me a do farming.” One of the Guyanese students said he would say, “Yesterday I was washing the clothes.” He provided no response as to how he would say the second sentence, only indicating that it would not be acceptable in CCE. Meanwhile, the student from Trinidad had problems with, “At present me a do farming,” and “Mary a sing now.” He said these were unacceptable in Trinidad, which comes as no surprise because the structures are Guyanese specific (Gibson, 1992). By engaging in this sentence Larsen & Karli | 11 analysis, our students confirmed that SAE and CCE have many of the syntactic differences described above, which is of great consequence to them in a U.S. academic setting. 2) To what extent do CCE speakers attending U.S. high schools recognize those differences? We had anticipated that in spite of the many syntactic differences between SAE and CCE, our students would only be aware of the phonological and lexical differences. In her study of Jamaican Creole speakers, Alicia Beckford asked men and women in a semi-rural community to describe how Jamaican Creole (Patois) differed from SAE. Despite the phonological, lexical, and syntactic variations between Patois and SAE, only 15% of men and 20% of women said the dialects varied in accent, vocabulary, and structure. The rest said that the dialects varied only in accent, or only in accent and vocabulary. A majority, then, were unable to recognize the very distinct syntactic differences (Beckford Wassink, 1999). Our findings differed from Beckford’s. When we asked the students to tell us how CCE and SAE were most different (in the pronunciation, lexicon, or syntax), one student indicated that the only major differences were in pronunciation and a small number of words, another that the biggest differences were syntactic, and the third student indicated that there were differences in all 3 areas. Although 2 of the students were aware that there were structural differences in the language, they were only able to provide us with a few examples. Those examples included: “I biliz” instead of “I’m going,” “Come na” instead of “Come here,” and “Carry come” or “Bring it come” instead of “Can you bring (it)? When we gave students sentences that were acceptable in some parts of the Caribbean, but unacceptable in SAE, the students were often unable to recognize that the sentences were problematic in SAE. The student with the most awareness of syntactic differences was the Larsen & Karli | 12 student from Trinidad, who correctly described the SAE issues in 5 of the 10 sentences. One student from Guyana correctly identified the problems in 2 of the 10 sentences and the other identified them in just 1 out of the 10 sentences. All three students identified the need for “is” in the sentence, “He rich,” which shows that they are aware of the need for copular verbs with predicates adjectives in SAE. This may have been obvious to the students because, of all the differences, it is one of the least complex. Our findings corroborate Beckford’s findings that while aware of phonological and lexical differences between CCE and SAE, CCE speakers are less cognizant of syntactic differences (1999). Even if they understand that there are structural differences, they may not be able to articulate these differences. Students’ failure to make syntactic distinctions between CCE and SAE makes sense if we consider that, “the similarities often mask the real differences between the two [dialects].” Furthermore, CCE speakers may not be able to distinguish the SAE syntactic structures because they often speak English along a continuum and don’t recognize the need for producing a single, consistent syntactic structure in SAE (Nero, 2000). 3. How are Caribbean Creole-English speaking students different from non-native English speaking students? CCE speaking students have different academic issues and face different challenges from their non-native English speaking peers. One challenge is that their dialect is not legitimized or recognized in most American schools. Creole English dialects are considered “not the right kind” because they are not the Anglophone dialects spoken in the “inner circle”, which includes U.S., Canada, and the U.K (Nero, 2000). English spoken in this “inner circle” is considered superior and is preferred to the Creole-English spoken in the Caribbean and India, not because it is linguistically superior, but because Creole-English has a history of being spoken by slaves Larsen & Karli | 13 (Nero, 2000). According to Sharon-ann McNicol, psychologist and author of Working with West Indian Families (Guilford Press), many CCE speakers “don’t like to speak in class because their teachers correct every sentence that comes out of their mouths. Asian and Latino children don't get that because it's understood that they're speaking a different language” (Sontag, 1992). This negative perception of CCE was also reflected in our findings. Two out of 3 of our subjects described their dialect with some words that had negative connotations. For example, one described his language as “broken” and “not proper”, while another described American English as “normal.” Another subject expressed his frustration with being a Caribbean CreoleEnglish speaker. “They think it’s cute,” he said, “but it’s irritating. I can’t get the job I want, they don’t understand you at the store. I can’t explain myself. And you don’t use it if you get pulled over by the police.” CCE speaking students have more difficulty using academic register and condensing information into direct, concise sentences with embedded clauses or nominalization of verbs in their writing. They are more likely to transfer speech register to their writing than their nonnative English speaking peers (Clacher, 2006). One reason is because the origin and history of Creole English is oral and not written. Their formal writing style is less developed and is more similar to informal speech. CCE speakers write long narratives, connecting additional information with “and” (paratactic) and “because” (hypotactic) clauses as if they are speaking to someone they know who shares their background knowledge and context. Their writing often lacks supportive details and examples to support their claims. They also use informal expressions or slang with the assumption that the reader understands what they mean (Clacher, 2006). CCE speaking students have difficulty recognizing and learning these differences in formal writing because of the lexical similarities between SAE and CCE. While they are often Larsen & Karli | 14 aware of their dialectic differences in pronunciation and some vocabulary, they often do not recognize subtle differences in grammar and sentence structures. For example, in our study, few of the students noticed the grammatical errors in the examples, such as lack of verb tense, inflection, or subject-verb agreement, according to Standard American English. This may be because they are constantly code-switching between both registers, which combines the two dialects to form an interlanguage. This interlanguage blurs and confuses the differences between SAE and CCE, which results in overgeneralizations and inconsistencies with SAE rules (Nero, 2000). This issue is similar to that of speakers of African-American Vernacular English, who are accustomed to switching back and forth between registers and fail to recognize or be motivated to learn the subtle and unique structures of academic registers (Nero, 2000). Like many non-native English speaking students in Washington, DC, CCE speaking students come to the U.S. with diverse backgrounds of formal education. Their struggles in academic writing depend on their educational backgrounds and their native dialect’s derivation from SAE. Some Caribbean students may have lower literacy in their native dialects. For example, research shows that the majority of Guyanese students have low functional literacy (Jennings 2000). In a study conducted at an urban university in New York City, a student from Guyana recalled that she only had to write one draft of her essays and the teachers just looked for the answer without requiring supportive evidence or examples (Nero, 2000). Similarly, one of our interview subjects from Guyana said that that he “did not take education seriously in Guyana” and that education was harder because “teachers didn’t help you” When asked if writing expectations were different in his native country he said that he “didn’t really have to write back then.” Larsen & Karli | 15 4. What can teachers of CCE speakers do to better support them? According to a study conducted by Shondel Nero at St. John’s University, in the last two decades there have been an increasing number of Caribbean immigrants in American classrooms, especially in New York City (Nero, 2000). The largest populations come from Jamaica and Guyana, and statistics shows that teachers are likely to see an increasing number of these students in their classrooms (Nero, 2000). Unfortunately, there is still no consensus among educators about whether CCE speakers should be considered native English speakers and if it is appropriate to place them in ELL programs (Adger, 1997). According to our study, half of the DCPS teachers surveyed feel that ELL classes are not beneficial for CCE speaking students and may even limit their potential. If they are placed in ELL, it should not be for more than one semester and the purpose should be for social and cultural acclimation to a new country and not to teach them English. Our research supports the view that while they may benefit from some ELL strategies, these strategies should be used in a mainstream classroom where students will not feel isolated or defensive. They are often more resistant to learning SAE in traditional ELL classes where they feel insulted and like they do not belong (Adger, 1997). Research shows that teachers do not know what to do with CCE speakers and fail to notice the differences between the grammatical structures of the languages (Nero, 2000). For example, while they often correct grammatical errors on students’ papers, they do not recognize them as errors stemming from language differences between CCE and SAE (Nero, 2000). Instead, teachers correct the errors assuming that the student is already familiar with the standard structures and expect the students to understand why they are wrong. In our teacher survey, 6 out of 8 teachers recognized differences in pronunciation, such as word stress and accent. Two out of 8 also recognized differences in vocabulary, with one Larsen & Karli | 16 ELL teacher adding that this was due to a British-based lexicon. Two out of 8 teachers found differences in grammar, such as eliminating verb tense and inflection for the third person singular. However, none of the teachers mentioned a need for specialized instruction in formal writing, and one teacher claimed that his CCE students often had more advanced academic writing skills than students from other countries. Teachers should also be trained in the grammatical structures of CCE as well as cultural sensitivity and the history of the language. For example, teachers should be familiar with common grammatical structures of CCE such as lack of inflections in verb tense, subject-verb agreement, copular verbs between nouns and adjectives, and plurals as well as unique structure of a + verb for present progressive and the habitual marker does. As shown in Nero’s study, many opportunities to highlight specific differences between SAE and CCE were missed because teachers failed to identify a syntactic or grammatical error as a dialectic difference (Nero, 2000). If teachers were trained in these differences, they could have personal conferences and mini lessons with students about why and how the structures are different. Even if there is no formal training available, teachers can conduct workshops in which they work together to analyze their students’ work. Nero’s study identified three types of effective programs that specialize in teaching SAE to CCE students: instrumental programs, where the native dialect is used to teach initial literacy, accommodation programs in which the dialect is not used by the teacher in instruction, but acceptable if used by students, and awareness programs, in which students get a holistic, sociolinguistic picture of their native dialect (Nero, 2000). All of these programs have had positive results and parental support, but the most successful programs have been the cultural awareness and accommodation programs, which have produced higher test scores in reading and writing in standard English, overall improved academic achievement due to greater cognitive Larsen & Karli | 17 development, increased motivation and self-esteem, and ability to notice the differences between the dialects (Siegel, 2008). One example of a successful awareness program is the Caribbean Academic Program (CAP) at Evanston Township High School in Illinois, historically one of the best high schools in the nation (Songtag, 1992). This program confronts the deep rooted negative attitudes attached to CCE by teaching students the rich history of the dialect and how it came to be a distinct language from SAE (Nero, 2000). Students also explore differences between the dialects of different islands within the Caribbean and perform plays in Creole (Nero, 2000). A study conducted on this program showed that while all students entered the program below the American norm on standardized tests, after a year, only 15 percent remained below average and 30 percent went on to honors courses (Sontag, 1992). Curriculum and classroom activities should reflect the diversity of the student population and legitimize and highlight their experiences and backgrounds. This is especially important for CCE speakers whose native language is often ignored or degraded in American society. Some empowering exercises for them would be write personal stories or poems in their home language and SAE or to read and interpret stories written by authors from their native countries. They can conduct research projects on their own language in which they are the class experts, compare and contrast their language structures with SAE, and present their findings to the class. They can role play, write scenarios, and discuss which contexts are appropriate for both their native dialect and SAE and how to easily shift between the two (Nero, 2000). All of these activities are not only empowering and liberating, but also help them self reflect and build their metalinguistic skills. Similarly, we noticed that our subjects were very enthusiastic about participating in our study on their native language, something that they Larsen & Karli | 18 probably never experienced before. We could see how proud they were to speak about their language and some of them offered to provide more resources to help us research further. Student attitudes about ELL classes CCE students have different attitudes about whether they need ELL services and how receiving these services make them feel. Some students feel insulted to be placed in low or intermediate ELL courses when they already speak English (Nero, 2000). Our subjects had different opinions about if CCE speakers should take ELL (or ESL) classes. One subject felt that “it depends on your ability. From my understanding, ESL is for if you hardly know English or have low academics back home. Before I came, I was about to graduate.” The student who admitted to having little education in Guyana agreed that ELL was good for him. He felt that he learned faster because “in ESL classes, they break it down for you, but not in mainstream.” The other subject from Trinidad thought it was important for him to be in ELL classes, but for social reasons. He said “if it wasn’t for ESL, I would’ve left school, gone to a place where more kids are from the Caribbean.” He added that if Caribbean students are placed in mainstream classes, they should be classes where “the teachers understand where we are coming from.” When asked how Roosevelt teachers could accommodate for their needs, our subjects suggested that they: “understand that we make mistakes”, “be more patient,” “don’t talk too fast”, “write things down”, and “ask questions to make sure we get it”. V. Conclusions and Suggestions for Future Research If given the opportunity to continue our research and analyze it on a deeper level, we could interview a larger and more varied sample of CCE speakers of different genders, ethnicities, and geographic regions, and tape or video record our interviews to capture their Larsen & Karli | 19 natural speech. We could also collect writing samples to capture their “natural writing” and ability to identify syntactic differences without being led by our questions. Writing samples would also enable us to analyze students’ specific difficulties with expository and formal writing to better meet their needs in the classroom. Our student interviews bore out a majority of the predictions we had related to phonological, lexical, and syntactic differences between CCE and SAE. Students confirmed most of the lexical differences and while the Guyanese students did not display all the phonological differences that were anticipated, we believe this is a result of the fact that they have all been in the U.S. for at least 2.5 years. Finally, the students confirmed that a great number of syntactic differences exist between CCE and SAE. These differences relate to markers for tense, subject-verb agreement, plurals, and the present progressive and habitual aspects. Overall, our study shows that syntactic differences are of most concern to teachers. Not only do they have the greatest implications for students’ academic success, but students are also the least aware of them. In all classrooms, teachers should explicitly teach CCE speakers how and when to navigate between CCE and SAE. Teachers need to provide different contexts or scenarios where students decide when and how to express themselves using the different grammatical structures. They need to directly compare and contrast sentence structures, especially subject-verb agreement, verb tenses, and inflections. They also need to explicitly teach formal and expository writing styles, such as nominalization and embedded clauses (Clacher, 2006). Our findings show that Caribbean Creole-English speaking students have different social and academic issues from non-native English speaking students and should be taught in different ways. Traditional ELL classes are not beneficial for CCE students because they do not meet Larsen & Karli | 20 their specific needs, which are identifying the subtle grammatical differences between dialects and using academic discourse in writing. The placement of CCE students in ELL classes should be temporary and based on reading and writing scores. The purpose of placement in an ELL program should be for the acclimation and socialization to a new culture. Since CCE speakers and teachers are often unaware of the grammatical differences between CCE and SAE, all teachers should be trained in history and structure of the dialect, as well as effective teaching strategies (Nero, 2000). Cultural awareness programs are often the most successful programs for CCE speakers because they learn to feel proud of their native dialect, its origin, and purpose (Siegel, 2008). Other successful activities encourage students to take ownership in their educations by choosing genres, texts, and topics that are written by Caribbean authors and highlight their cultural backgrounds. Students can be class experts in their dialects and compare and contrast them with other students (Nero, 2000). This increases their motivation to learn and ability to separate the languages, find connections and differences between them, and the contexts in which each language is appropriate (Siegel, 2008). Above all, students should be taught that their native dialect is not inferior, but instead a tool that can be used in different social contexts and settings (Songtag, 1992). They should consider themselves bilingual or bidialectal, with a skill or talent that they can successfully employ to communicate in different situations, much like an ELL student whose native language is not English. Their native dialect should be seen as a bridge to their social, academic, and professional development, not an obstacle. Larsen & Karli | 21 References Adger, Carolyn Temple. “Issues and Implications of English Dialects for Teaching English as a Second Language. TESOL Professional Papers #3. 1997. Beckford Wassink, Alicia. “Historic Low Prestige and Seeds of Change: Attitudes toward Jamaican Creole.” Language in Society. Vol. 28, No. 1 (Mar., 1999): 57-92. Clachar, Arlene. “Re-examining ELL Programs in Public Schools : A Focus on Creole-English Children’s Clause-Structuring Strategies in Written Academic Discourse.” Forum on Public Policy: A Journal of the Oxford Round Table. (Fall 2006): 1-38. Gibson, Kean. “The Ordering of Auxiliary Notions in Guyanese Creole.” Linguistic Society of America. 62.3 (Sep., 1986): 571-586. Gibson, Kean. “Tense and Aspect in Guyanese Creole.” International Journal of American Linguistics. Vol 58, No. 1 (Jan., 1992): 49-95. Jennings, Zellyn. “Functional Literacy of Young Guyanese.” International Review of Education. Vol. 46, No ½ (May, 2000): 93-116. Le Page, R.B., and Andree Tabouret-Keller. Acts of Identity. Cambridge, Great Britain; Cambridge University Press, 1985. Print. Nero, Shondel J. “English is My Native Language.. or So I Believe.” TESOL Quarterly. Vol. 31, No. 3 (Autmun, 1997): 585-593. Nero, Shondel J. “The Changing Faces of English: A Caribbean Perspective.” TESOL Quarterly. Vol. 34, No. 3 (Autumn, 2000): 483-510. Siegel, Jeff. “Pidgin in the Classroom.” Educational Perspectives: Journal of the College of Education/University of Hawaii at Manoa. Vol. 41. Numbers 1 and 2. (2008). Sontag, Deborah. “Caribbean Pupils’ English Seems Barrier, Not Bridge.” New York Times. 1992. Larsen & Karli | 22 VI. Appendix Student Interview Question Bank Student Name: ________________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________________ Gender: _____________________________________ Grade in School: ______________________________ Place of Birth: ________________________________ Ethnicity: ____________________________________ First Language: _______________________________ Time in the U.S.: _____________________________ Interview Date: ________________________________ 1. Do people speak English differently depending on where they are from? Can you give any examples? 2. Do you hear different varieties of English throughout the day? Where? Spoken by whom? 3. How often do you hear CCE spoken? 4. Where do you speak your first language? Standard American English? Larsen & Karli | 23 5. Can you say things in your first language that you can’t say in SAE? If yes, can you give me some examples? 6. Can you say things in SAE that you can’t say in your first language? If yes, can you give me some examples? 7. How would you describe your first language? 8. How would you describe SAE? 9. Where is it better to speak CCE? Standard American English? Why? 10. When you first came to the U.S., was it difficult to understand spoken English here? If so, why do you think that is? Larsen & Karli | 24 11. When you first came to the U.S., was it difficult to be understood when speaking to English speakers born in America? If so, why do you think that is? 12. Which is most difficult for you in school: reading, writing, speaking, or listening? 13. How are expectations for writing different here, if at all? 14. Do you think students who are from the Caribbean and speak English should be put in ESL classes? Why? Why not? 15. Are there ways that Roosevelt teachers could better support you? 16. Do you think CCE and SAE are most different in pronunciation, vocabulary, or sentence structure? Larsen & Karli | 25 17. Now I’d like to examine some specific ways that your first language and SAE may or may not be different. First, I will ask you to provide me examples, if you can think of any. Then, I will give you examples and ask you to tell me if there are any differences. Pronunciation 1. Are there any pronunciation differences you notice? Word 1. CCE Difference Larsen & Karli | 26 2. Please pronounce each word as you would when speaking CCE. Word CCE Difference Thing That Can’t Home Something Don’t Father You Make Body Vocabulary 1. Are there words in SAE that are different in CCE and SAE? SAE CCE Larsen & Karli | 27 2. Can you tell me what these words means are CCE? SAE? SAE CCE Billboard Pig Arm Leg Another A’Next Sentence Structure 1. Are there sentences that you say in SAE that you say differently in CCE? Standard English Sentence CCE Sentence Larsen & Karli | 28 2. Sentence Analysis: Read each sentence below. Then please note if you can you say these sentences in your first language and also in Standard American English. If you can’t say them, write how you would say them. Example Sentence Okay in Your First Language? Okay in Standard American English? 11. He rich. ______Yes, it’s fine. ______Yes, it’s fine. ______No, you have to say: ______No, you have to say: ______Yes, it’s fine. ______Yes, it’s fine. ______No, you have to say: ______No, you have to say: ______Yes, it’s fine. ______Yes, it’s fine. ______No, you have to say: ______No, you have to say: 12. She tell me everything. 13. Yesterday, I wash the clothes 28 Larsen & Karli | 29 Example Sentence Okay in Your First Language? Okay in Standard American English? 14. Blake carried guns and ______Yes, it’s fine. ______Yes, it’s fine. ______No, you have to say: ______No, you have to say: ______Yes, it’s fine. ______Yes, it’s fine. ______No, you have to say: ______No, you have to say: ______Yes, it’s fine. ______Yes, it’s fine. ______No, you have to say: ______No, you have to say: threaten other people. 15. Students does go on like that. 16. He does go to church every week. 29 Larsen & Karli | 30 Example Sentence 17. At present, me a du (do) farming. Okay in Your First Language? Okay in Standard American English? ______Yes, it’s fine. ______Yes, it’s fine. ______No, you have to say: ______No, you have to say: ______Yes, it’s fine. ______Yes, it’s fine. ______No, you have to say: ______No, you have to say: ______Yes, it’s fine. ______Yes, it’s fine. ______No, you have to say: ______No, you have to say: 18. Mary a sing now. 19. At half-past five me (mi) de a work. 30 Larsen & Karli | 31 31