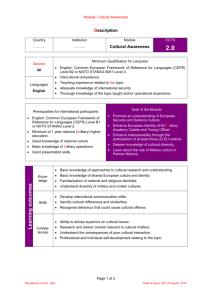

Intercultural Competences Conceptual and Operational Framework

advertisement