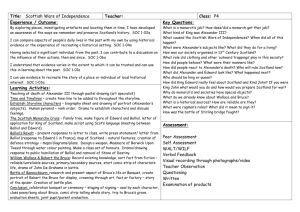

Key figures

advertisement

KEY FIGURES Key figures Alexander III (reigned 1249–1286) King from the young age of seven, Alexander nevertheless is seen as a highly effective king, and his reign is often referred to as the Golden Age of medieval Scotland. Alexander had been on good terms with En gland, firstly with Henry III, who allowed his eldest daughter to marry the Scottish king, and then with his brother-in-law Edward I. Alexander had sworn fealty to Edward for his English lands, but had steadfastly refused to accept Edward as overlord for his kingdom of Scotland. Alexander III reigned over Scotland during a time of peace and prosperity. More land was turned over to agriculture, and monasteries and abbeys continued to grow and flourish. Trade with the continent brought much needed supplies and bolstered the economy. Alexander even managed to push the boundaries of Scotland further west, when he defeated the Norwegian king at the Battle of Largs (1263) and added all of the Western Isles to his domain. Alexander III, however, failed to secure his succession. With both his first wife and last remaining son dead, Alexander agreed to marry again. It was during a trip to visit his new wife, Yolande, that he was killed falling off his horse. This left only the three-year-old Margaret, Maid of Norway as the heir to the Scottish throne. Margaret Maid of Norway Margaret was the daughter of King Eric II of Norway and Margaret, daughter of Alexander III. She was born in 1283 and her mother died in childbirth. Margaret had been accepted as heir apparent by the Scottish nobility, while Alexander III still lived. However, it was assumed at the time that the king would father another son. After his death, however, Margaret’s father, the King of Norway, was anxious that his daughter would receive her birthri ght and become queen of Scots. She died on her way to Orkney in 1290; her remains were taken back to Bergen and buried alongside her mother. Edward I, King of England (reigned 1272–1307) Edward was a powerful and successful king, who had taken part in t he ninth crusade, conquered Wales and incorporated it into the kingdom of England in 1284. Edward was a keen lawyer, and took a great deal of interest in the workings of the government. An able tactician and brave warrior, Edward was admired by his barons, but not always liked. His heavy-handed approach and WARS OF INDEPENDENCE (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 1 KEY FIGURES constant interference in their business was quite often resented. However, there were no serious revolts to royal authority during his reign. There is a lot of historical debate concerning Edward’s motives after the death of Alexander III. Did he, as some historians believe, see a chance to profit through Scotland’s misfortunes by exerting his claim of overlordship? Or, as other historians argue, was he simply looking to maintain a secure northern border during this period of troubles with France? The Scottish clergy The Scottish church was determined throughout this period to maintain its independence from the authority of the Archbishop of York. Scotland had no archbishop, but had secured the status of ‘special daughter, no one between’ from the Pope in 1174. This was further enforced by a papal bull in 1192 emphasising the freedom of the Scottish church from interference from York. Any threat to the independence of Scotland would have been a threat to the independence of the Scottish church. In part this explains the almost fanatical support of the Scottish church throughout the war. Bishop William Fraser As Bishop of St Andrews, Fraser held an important position within the kingdom. He was a staunch supporter of the Community of the Realm, having served as guardian for the Maid of Norway. Fraser and Bishop Wishart of Glasgow were instrumental in getting the Parliament of Scone to accept Margaret as heir and queen. Fraser was keen to avoid civil war in Scotland, and when Margaret’s death was discovered he feared a coup d’état by Robert Bruce, Lord of Annandale. His decision to ask Edward for help has often been criticised by some historians. However, this is with the benefit of hindsight. He worked tirelessly in his defence of the independence of the church. Robert Bruce, Lord of Annandale Also known as ‘Robert the competitor’, the Lord of Annandale was the grandfather of the future King Robert I. An elderly man full of ambition, he must have realised that his claim was inferior to that of John Balliol. Some historians believe that his posturing and aggressive threats to make war before and after the death of Margaret show he suspected that his legal position was weak. 2 WARS OF INDEPENDENCE (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 KEY FIGURES John Balliol John was a significant landholder in Scotland, England and France. His grandmother, Margaret, was the eldest daughter of David, Earl of Huntingdon, thus giving him a strong claim to the vacant throne. Some historians have put forward the idea that John was a weak man, and this was the reason that he was chosen by Edward to become King of Scots. It is widely accepted, however, that his claim was legally the strongest, something Edward, an expert in the law, would have understood. John of Hastings An English knight who had fought several times for Edward I in the Welsh wars, John was the grandson of Ada, the youngest daughter of David, Earl of Huntingdon. John had argued that Scotland should be split up into three, and each of the surviving descendants of Earl David given an equal share. There were precedents for this happening in English law, and it had applied to baronies before. However, Edward I agreed that Scotland was a kingdom in its own right and that this case should not apply. WARS OF INDEPENDENCE (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 3