History The Treaty of Union Resources

advertisement

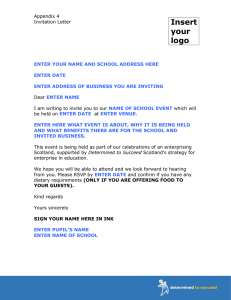

NATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS CURRICULUM SUPPORT History The Treaty of Union Resources [HIGHER] PRIMARY SOURCES The Scottish Qualifications Authority regularly reviews the arrangements for National Qualifications. Users of all NQ support materials, whether published by Learning and Teaching Scotland or others, are reminded that it is their responsibility to check that the support materials correspond to the requirements of the current arrangements. Acknowledgement Learning and Teaching Scotland gratefully acknowledges this contribution to the National Qualifications support programme for History. © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 This resource may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational purposes by educational establishments in Scotland provided that no profit accrues at any stage. 2 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 PRIMARY SOURCES Contents Secondary sources 4 Curriculum for Excellence ideas 26 Assessment is for Learning ideas 29 Website links 31 Teaching plan 34 Extended essay 36 SECONDARY SOURCES Secondary sources Issue 1: Worsening relations with England J D Mackie, on the immediate cause of the Revolution of 1688 –9 following James VII and II’s policy of appointing Roman Catholics to high office, from A History of Scotland, pp242–3: The birth of a Prince of Wales in June convinced England that James’s policy would survive his death, and the arrest of the ‘Seven Bishops’ stirred into activity resentment already awakened by the promotion of Roman Catholics to power and office. Before long William of Ora nge received an invitation from English magnates, both Whig and Tory, to which, after some negotiation, he replied that he would come to ensure that all pressing questions of Church and State should be settled by a free Parliament. A I Macinnes, on the Claim of Right, from Union and Empire: The Making of the United Kingdom in 1707, p87: Of greater constitutional significance was the unshackling of Court control over the Scottish Estates at the Revolution, which was also marked by a secular addition to the country’s burgeoning written constitutions. Without recourse to the religious imperatives of covenanting, the Claim of Right, issued by the Convention in April 1689, stressed the fundamental, contractual nature of the Scottish state by deposing James VII rather than following the English fiction of abdication. Michael Lynch, on the Glencoe Massacre and its place in the context of government attempts to control the Highlands, from Scotland: A New History, p307: The product of a moderate Highland policy wh ich went badly wrong, the Glencoe massacre was an accurate mirror of the divisions and different lines of communications which existed within William’s government and had indeed permeated every Stewart government throughout the century... The effects of the massacre were complicated but to contemporaries seemed more clear-cut than they really were: the government had lost control of the Highlands; the always fragile balance between an understanding with the 4 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 SECONDARY SOURCES chiefs implying their acceptance of the regime a nd a government presence to enforce it was never more brittle than in the two decades after 1692. Christopher A Whatley, on the key issues affecting Scotland in the years after the Revolution of 1688–9 and their link to eventual union, from The Scots and the Union, p139: Four factors in the 1690s tipped Scotland over the edge of an economic abyss that was to have profound political consequences for the nation’s history. They were, first, a series of harvest failures – King William’s ‘Ill Years’; second, the deleterious effects of the Nine Years War, particularly the loss of the French market; third, the erection of protective tariffs by countries overseas which blocked the export of certain Scottish goods; and, finally, what would become the disaster of Darien, Scotland’s extraordinarily ambitious scheme to establish a trading colony in south America that would form a commercial bridge between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. As it happened, the outcome – eventually – was incorporating union, but the decade of crisis might equally have produced a very different result. J D Mackie, on the difficulties between William and the Scottish Parliament in addition to disagreement over the Committee of the Articles, from A History of Scotland, p254: Confronted by a Parliament becoming more independent and more representative, William relied upon the expedient of offering posts and gratifications to nobles and burgesses, but his relations with Scotland remained uneasy. Apart from the causes of friction already mention ed, there was a permanent underlying cause of difference in the matter of foreign policy. William from 1689 to 1697 was at war with France, and France was Scotland’s old ally. Scottish money was spent, and Scottish lives were lost – the Cameronians, for example, suffered dreadfully at Steenkirk (1692) – in a quarrel which was repugnant to Scottish sentiment and which injured an old established Scottish trade. The ill-will between the two governments came to a head with the failure of the ‘Darien Scheme’. Paul Henderson Scott, on King William’s role in English efforts to deny foreign investment in the Company of Scotland, from The Union of 1707: Why and How, pp16–7: William gave assent to the Act as King of Scots, but as King of England he did all he could to frustrate it. English trading interests and the English Parliament saw the proposals for a Company of Scotland as a potential rival to the English East India Company. On 17th December 1695 the Lords and Commons presented an address to the King protestin g against ‘the great prejudice, inconvenience and mischief’ that would result to English trade SECONDARY SOURCES from the Scottish Act. William replied: ‘I have been ill -served in Scotland, but hope some remedies may be found to prevent the inconveniences which may arise from this Act’. Under the Act establishing the Company 50 per cent of the share holding was reserved to Scottish residents, and 50 per cent was available to English investors. The English share was oversubscribed within a few days, but was all withdrawn when royal displeasure was made known. English diplomatic influence in Europe discouraged continental investment. The English Company and English Ambassador to Spain virtually encouraged a Spanish attack on the Scottish settlement. Christopher A Whatley, on William’s reluctance to win the hearts and minds of Scotland despite there existing a willingness in Scotland to support him, from The Scots and the Union, p140: Attempts by Scottish ministers throughout William’s reign to persuade him to visit Scotland, however, fell on deaf ears. Jacobite conspiracies south of the border were endemic prior to 1696, when a plot to assassinate the king was uncovered. This, followed in 1697 by the signing of the Treaty of Ryswick in which Louis XIV agreed to withdraw succour from William’s enemies, and the arrival of what was received as a blessed peace, did much to revive support from the king. Douglas Watt, on the Scots who invested in the Company of Scotland , from The Price of Scotland: Darien, Union and the Wealth of Na tions, p47: At the heart of the history of the Company of Scotland was a group of individuals who never travelled to Darien, who never felt the heat of the Central American jungle or smelled the stench of death in the huts of Caledonia, and as a result have not featured highly in the accounts of historians. These were the men and women who, in very large numbers for the period, became shareholders in the Company and provided the money to fund the venture. They spent the years from 1696 to 1707 on an emotio nal rollercoaster between ecstasy and despair, waiting expectantly for each crumb of news. An examination of who they were, and why they were willing in such numbers to invest in a joint-stock company in 1696, is of central importance not just to the history of the Company but also to explaining the passage of the Treaty of Union through the Scottish parliament in 1707. A I Macinnes, on problems facing William in Scotland in 1700, from Union and Empire: The Making of the United Kingdom in 1707 , p89: By this juncture, William was facing more formidable opposition from within Scotland. A Country interest had emerged as a confederated opposition, intent on using Darien as a means not of attacking the king directly but of removing the dominance of the Court and English ministries over Scottish affairs. 6 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 SECONDARY SOURCES William, 4th Duke of Hamilton, a sympathiser with the exiled Stuarts, was suspected of involvement, but not directly implicated, in the failed plot to assassinate William of Orange at the outset of 1696. He led this incipient political party, having returned to public life during the Darien crisis. Although Hamilton was ambitious for office he was financially vulnerable. Paul Henderson Scott, on English influence over Scottish affairs even before Union, from The Union of 1707: Why and How, p22: The domination of England was not confined to foreign policy, but extended also to a large measure of intervention in the internal affairs of Scotland. The appointment of officers of state, that is the ministers of the S cottish Government, and all other senior appointments, were made nominally by the monarch, but again on the advice of the English Government. Money raised by taxation in Scotland was transferred to London and controlled by the English Treasury. The ministers of the Scottish Government were not only appointed, but were paid by London, and were instructed nominally by the monarch, but again in practice by English ministers. The Scottish Parliament could debate as it please and pass Acts as it wished, but agai n they required royal assent from London. It is therefore not surprising that English Governments had become accustomed to treating Scotland as a dependency under their control. Michael Fry, on the ‘Seven Ill Years’, from The Union: England, Scotland and the Treaty of 1707, p17: It was through acts not just of man but also of God that Scotland suffered affliction. Lying at the climactic limits of primitive agriculture, she had often gone hungry. But the famine of the 1690s went beyond anything known or remembered. The whole nation seemed to fall back to a lower stage of development. The economy ground to a halt as merchants exported coin to buy grain from abroad. The people reverted to barter. The state struggled to function without the taxes it could not collect. Highland bands debouched in quest of sustenance on the Lowlands. The Jacobites spoke of ‘King William’s seven ill years’. That term drew an analogy between him and the wicked Pharaoh of the Bible to suggest a divine judgement on the Scots for the sin of dethroning James VII and II. Douglas Watt, on immediate reaction within the East India Company to the founding of the Company of Scotland in 1695 , from The Price of Scotland: Darien, Union and the Wealth of Nations, pp38–9: On 4 December the directors resolved that one or more ships should be fitted out for the East Indies and sail for Scotland as soon as possible. Plans were also to be put in place for a Scottish capital raising. On the same day the East SECONDARY SOURCES India Company appointed a committee to dr aw up for the House of Lords a list of reasons why the Scottish act of parliament was detrimental to the trade of England. Panic spread through the English company as rumours circulated that several of their own directors and shareholders had subscribed to the ‘Scotch Act’. It was declared that those who invested would be excluded from the court and directors were forced to swear an oath that they had not done so. Paul Henderson Scott, on how the place of the Darien disaster in events leading to Union, from The Union of 1707: Why and How, p20: It has been said that the Darien episode made a Union with England more likely or even that it led directly to it. One effect was certainly to weaken the bargaining strength of Scotland and reduce her capacity to res ist. On the other hand, it made any form of amicable arrangement less likely by increasing the Scottish distrust of England. Michael Fry, on the appointment by Queen Anne and responsibilities of Godolphin, from The Union: England, Scotland and the Treaty of 1707, p34: Anne had so far played next to no part in politics and remained almost unknown outside a circle of ministers. But she set off resolutely enough and dismissed the Whig Ministers she inherited. She replaced them with Tories or men sympathetic to Tories, notably Sidney Godolphin, among the greatest fiscal experts of the day. The range of qualities in Godolphin made him in essence the queen’s most senior civil servant, brilliant if testy, with the experience and capacity to run the government’s f inances, patronage, domestic policy and relations with Scotland (the rest of his time was his own; he liked nothing so much as a flutter on the horses). He had as little knowledge as most Englishmen of the Scots, though he knew what he wanted: a stable Scotland. But stability was not something Scotland offered. Douglas Watt, on the effect of the Darien disaster on Scottish politicians’ feelings towards England, from The Price of Scotland: Darien, Union and the Wealth of Nations, p175: Anti-English sentiment was intensified by debates in the English Houses of Parliament in January and February [1700] on the issue of Darien, and a Union proposal by William. The English Tories killed off the attempt to reconstitute the relationship between the two kingdoms wi th bitter attacks on the Scots. Sir Edward Seymour, an old Tory member of the Commons, famously stated that Scotland ‘was a beggar, and whoever married a beggar could only expect a louse for a portion’. The English parliament complained about another pamphlet, An Enquiry into the Causes of the Miscarriage of the Scots Colony at Darien, which was condemned as a ‘false, scandalous, and 8 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 SECONDARY SOURCES traitorous libel’ and ordered to be burnt. George Horne thought the nations might be ‘dasht against one another like two pi tchers’. There was a fear in government circles of a coup and Marchmont was keeping a careful eye on the loyalty of army officers’. A I Macinnes, on the significance of Scottish legislation in 1703, from Union and Empire: The Making of the United Kingdom in 1707, p259: There were two key Acts restricting the prerogative powers of the monarchy. The first was the Act anent Peace and War which laid claim not so much to an independent foreign policy as to a binding commitment on Queen Anne’s successor, if the common monarchy continued, to gain consent from the Scottish Estates before any war could be declared... In the case of the Act of Security, however, the presumption was made that the common monarchy would not continue unless, prior to the death of Queen Anne, ‘there be conditions of government settled and enacted’ which recognised: the honour and sovereignty of the separate crown and kingdom; the freedom, frequency and power of parliaments; and that the religion, liberty and trade of the nation should not be subject to English or any foreign interference. Paul Henderson Scott, on Andrew Fletcher’s ‘Twelve Limitations’ proposed during the debate leading to the Act of Security in 1703, from The Union of 1707: Why and How, p27: Fletcher proposed a series of ‘Limitations’ on royal powers which would have transferred them entirely to Parliament. The monarch would be obliged to sanction all laws passed by parliament and would not have power to make peace or war or conclude treaties. ‘All places and offices, bot h civil and military and all pensions shall ever after be given by parliament’. To provide Scotland with a force to defend itself, ‘all fencible men of the nation, betwixt sixty and sixteen’ would be armed. Any king who broke any of these conditions would be declared to have forfeited the Crown. A I Macinnes, on the political tactics of the Jacobites in the years leading to 1707, from Union and Empire: The Making of the United Kingdom in 1707 , pp249–50: By the accession of Queen Anne, Jacobite plotting ha d an increasingly Scottish focus, partly on account of the claimed facility of Scottish Jacobites to raise the Highland clans and partly as a reflection on the increasing unpopularity of William of Orange in Scotland. Plots consistently featured Hamilton, and other politicians, deemed not amenable to the direction of the English ministry, who came to be associated with the Duke in the Country party in 1698. In turn, their purported clandestine association with the French during the War of the Spanish Succession served as justification for the SECONDARY SOURCES English ministry to countenance armed intervention in Scotland from 1703, as the latter struggled to come to terms with the legislative war instigated by the Scottish Estates’ refusal to accept the Hanoverian Successi on. However, the Scottish Jacobites and their associates within the Country party preferred to exhaust parliamentary means to oppose union rather than commit to an armed rising, a position sustained until the Union came into operation in May 1707. Paul Henderson Scott, on those who faced the greatest threat from the Aliens Act of 1705, from The Union of 1707: Why and How, p37: The threats in the English Aliens act were aimed particularly at the lords. Many of them had a financial interest through their ho ldings of land and exporters of the agricultural products now threatened with embargo. Also, since the Union of the Crowns several lords had acquired estates in England through marriage which were at risk from the threat to ban the inheritance of property. Issue 2: Arguments for and against union with England Christopher A Whatley, on the importance of trade to the argument for Union, from The Scots and the Union, p96: In the second half of the seventeenth century a new consideration began to come to the fore: trade. The prospect of untrammelled Scottish involvement in the Atlantic trade appealed to Scottish merchants whose activities from 1660 were restricted – but not blocked – by the English navigation acts which had reduced Scots to the status of foreigners. This, allied to the growing dependence of the Scots on English markets, aroused enthusiasm for a ‘union of trade’, particularly among the mercantile communities on the west coast; in Glasgow there were hopes that William’s appointment as King migh t be accompanied by such an arrangement. The appeal of free trade however was by no means confined to those on the Atlantic seaboard, although there are historians who suspect that politicians simply used this to cloak their real reasons for supporting union – that is, to strengthen the monarchy. Karen Bowie, on the political, religious and economic benefits which supporters of Union hoped for, from T M Devine, Scotland and the Union: 1707–2007, p41: New research has made it clear that parliamentary votes for the Treaty of Union rested on a core commitment to the Revolution of 1688 –9 and a desire to secure Scotland from a return of the Catholic Stuarts ousted in the Revolution. Many also wished to retain the Presbyterian Church, which had been re-established in the Revolution settlement with the removal of the 10 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 SECONDARY SOURCES Stuarts and the Episcopalian Church. Lastly, some hope that the Union treaty’s economic concessions, including free trade with England and its colonies, would allow the Scottish economy to recover f rom a deep recession dating from the 1690s. The evidence of the public debates on union suggests that this parliamentary support for the treaty reflected opinions held by a wider, though still limited, constituency. Christopher A Whatley, on arguments against union based on English ulterior motives, from The Scots and the Union, p175: There were those who wanted to resist any moves towards union, interpreting English interest in this as a means of diverting the attention of Scots from Darien and their rights there, and a device ‘to make us greater slaves than the Irish’; ‘all true patriots’ were urged to shun Sir James Ogilvy, Viscount Seafield, who had been appointed as an emissary by the court and sent north in January 1700, apparently with £12,000 to distribute and ‘buy us all over like a pack of beggarly dishonourable Rogues and Villains’. At this stage, even though attacks on those men who had obtained high office were often informed as much by jealousy as any genuine doubts their detractors could have about their patriotism, such reservations did have some substance. J D Mackie, on the steps taken to discuss union immediately after the accession of Queen Anne, from A History of Scotland, pp257–8: In May 1702 she gave her assent to the Act of the Engl ish Parliament empowering her to appoint Commissioners and in June recommended Union to the Scottish Parliament which reassembled on the ninth of that month. In that parliament the opponents of union with England suffered a reverse of their own making. Hamilton, complaining that parliament had not met, according to an Act of 1696, within twenty days after the king’s death, protested that its sitting was illegal and then dramatically walked out with fifty-seven of his supporters. His action was popular in th e streets, but in the House it left control to the Court interest which passed a series of Acts confirming the Revolution Settlement to win Presbyterian support and asked the Queen to appoint Commissioners to negotiate with those of England. In November Commissioners from both sides met at Whitehall but, though they agreed on general principles, they differed on economic details and, in February 1703, adjourned without reaching a conclusion. Christopher A Whatley, on the growing case for Incorporating Unio n even in Scotland, from The Scots and the Union, p217: Even before the final vote on the Act of Security it had become evident that in court circles in England, the preference was for an incorporating union. Incorporation was not a novel idea in Scotland though, and there had been SECONDARY SOURCES fairly strong support for a negotiated union of this kind up to the end of 1702. Nor was the union option without its supporters in 1704. Lockhart was irritated that there were so many. Douglas Watt, on the points of discussion between Scots and English commissioners in 1702 and 1703, from The Price of Scotland: Darien, Union and the Wealth of Nations, p224: The negotiations of 1702/3 reached agreement on a number of points: free trade between the two kingdoms and the English plantations, a commitment to the same level of taxes on imports and exports and the abolition of the Navigation Acts. An area of difficulty remained the debts England had accumulated since the Revolution and whether Scotland should have to pay a proportion of them after Union. By 28 January 1703 there was agreement that neither kingdom should be burdened with debts contracted before the Union, that no duties or taxes levied in Scotland should be applied to paying English debts, and that there should be time allowed for the Scots to reap the benefit of free trade before equal taxation was introduced. Negotiations continued but reached deadlock over the issue of the Company of Scotland. Michael Lynch, on the new composition of the Scottish Parliament after 1703 and the effect of this on the arguments for and against Union, from Scotland: A New History, p311: In 1703 an event of great significance took place – or so it seemed at the time. An election produced a new map of Scottish politics, in which both the Court and Country party were the losers; the Jacobites (who now masqueraded under the name of Cavaliers) made significant gains, and a ‘New party’, under the leadership of Tweeddale, broke up the old cohesion of the Countrymen. Union, the failed product of the two old parliaments, now seemed further away than ever for in England the Whigs had been driven from office. This was the Scottish parliament which in the course of 1703 wrested control of the House from the court, passed the Act of Security – a specific riposte to the act of Settlement – by a clear majority of fifty-nine votes in August, and in the Act anent Peace and War took decisive steps to prevent Scotland again being dragged into a foreign war by Anne’s successor. Paul Henderson Scott, on the Scots Commissioners conceding to the English Commissioners over the notion of Incorporating Union, from Andrew Fletcher and the Treaty of Union, p153: The immediate collapse of the Scottish position was to be expected from a group of negotiators hand-picked as supporters of the Court, with the single exception of Lockhart. As the passage from Clerk’s Memoirs shows, the Scottish Commissioners had decided in advance that the so -called ‘federal’ 12 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 SECONDARY SOURCES approach was ‘ridiculous and impracticable’ and that the only U nion which could survive was one that was ‘incorporating and perpetual’. Incorporation would be perpetual because the Scots would have surrendered any means of establishing and asserting an independent point of view. The Scottish Commissioners had made a gesture by opening with a proposal which would have preserved the Scottish Parliament because they knew that it ‘was most favoured by the people of Scotland’; but it was no more than a gesture and an excuse with which they could later use to justify their s urrender. They wanted to be able to argue that they had at least tried. J D Mackie, on the popular shows objections to union made in 1706, from A History of Scotland, p262: When the draft Treaty was presented to the Scottish Parliament in October 1706, and its terms became public, it was met with a howl of execration throughout the land which was, no doubt, fomented by the Jacobites, but which also represented a feeling that Scotland had been sold to the English. In Edinburgh, Glasgow and Dumfries, there was mob violence and, as debates in parliament continued, petitions came in from about a third of the shires, a quarter of the royal burghs, and from some presbyteries and parishes who feared that the Kirk was in danger. Michael Fry, on the unsuccessful union negotiations which took place in 1702, from The Union: England, Scotland and the Treaty of 1707 , p41: After the opening speeches the two sides sank into a morass of argument about trade. At least they at once identified a central issue. Right through the coming negotiations – in both this first, abortive round and in the later, successful one – the English evinced not the slightest interest in any of the Scots’ alternatives to an incorporating Union (or Union of Parliaments): limitations on the Crown, a federal system and so on. None could from England’s point of view answer the purpose of the exercise, which was to dismantle any rival political authority in Scotland or indeed any possibility of it. So all attempts at compromise over the absolute supre macy of the Parliament at Westminster were to the English wholly immaterial, mere quibbling irritants. Michael Lynch, on the proportion of Scottish MPs to be created in the new proposed British Parliament, from Scotland: A New History, p312: The allocation of forty-five seats in the Commons on a basis of thirty to the shires and fifteen to the burghs caused numerous protests, but protest turned into outrage when the ministry revealed that the first members in the new SECONDARY SOURCES parliament would be returned not by means of a fresh election but by nomination – in effect as clients of the ministry itself. Christopher A Whatley, on the arguments put forward in various addresses from burghs to Parliament that union would dishonour Scotland’s traditional independence, from The Scots and the Union, p282: The defence of Scotland’s honour and independent sovereignty, as embodied in its Parliament and the ‘fundamental laws and constitution of this Kingdom’, was paramount and based on a near -universal belief that this had been ‘valiantly maintained by our worthy ancestors, for more than the space of Two Thousand years’ – and which should be ‘transmitted to succeeding generations’. It was partly because the crown was the symbolic artefact by which this continuity was maintained that its retention in Scotland was so important an issue. Some talked of the sacrifice of blood and of former patriots – ‘greater people than we’, ‘their memory extinct’; the parishioners of Larbert, Dunipace and Denny condemned incorporation as a ‘dread ful act of ingratitude to God’ and ‘a most unaccountable act of injustice to ourselves and posterity’, a sentiment that was shared if anything with greater fervour in Cambusnethan. The inhabitants of the parishes of Bothwell and Kilbride went even further, echoing the Declaration of Arbroath in their undertaking to ‘venture with all our lives and all that is dear to us’, to defend Scottish liberties and the Reformation for which their forefathers had ‘wrestled’. Issue 3: Passing of the Act of Union Douglas Watt, on the eventual financial aid given to Company of Scotland investors by the English government, from The Price of Scotland: Darien, Union and the Wealth of Nations, p220: As part of negotiations over an Incorporating Union between Scottish and English commissioners in 1706, a very large lump sum of money emerged called the Equivalent, which was to be paid to certain Scots on achievement of Union. Most of it was earmarked for the shareholders of the Company of Scotland and was an unusual departure in corporate history; a shareholder bail-out with cash provided by a foreign government. Not only were the investors to receive all the cash they had paid to the Company but also, amazingly, interest payments of 5 per cent per annum, as if their money had been invested in some bank deposit or gilt -edged government bond, rather than a company that had lost every penny of its capital. This was an extraordinarily handsome return for the shareholders – a bail-out of 142 pence in the pound – and was a truly incredible result for the directors, who had squandered the capital of the company and now, as major shareholders, were to be generously rewarded for their mismanagement. 14 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 SECONDARY SOURCES A I Macinnes, on the early days of the Squadrone Volante, from Union and Empire: The Making of the United Kingdom in 1707, p264: This grouping, never more than thirty from all three estates, which was to form the New Party, later the Squadrone Volante, under the nominal leadership of the Marquis of Tweeddale, were not simply disgruntled Dari en investors opportunely seeking office to recoup their losses, and held together by political expediency. They were a tight -knit band drawn mainly from Lothian and the Borders, with ties of kinship reinforcing local association. With limited support from the lesser burghs, they represented landed enterprise rather than overseas trade in their commercial commitments. Michael Fry, on the ‘Mother Caledonia’ speech made by Belhaven on the opening day of the Treaty of Union debate, from The Union: England, Scotland and the Treaty of 1707, p261: Belhaven answered with a speech which has been held up as a masterpiece, though more to the taste of his own age than of ours. It built up its effect by striking tableaux of a future Scotland: ‘I think I see a free and independent kingdom delivering up that which all the world hath been fighting for since the days of Nimrod…’. Proceeding to religion, Belhaven went on: ‘I think I see a national Church, founded upon a rock, secured by a Claim of Right…’. Turning to address his peers, he said, ‘I think I see the noble and honourable peerage of Scotland now divested of their followers and vassalages and put upon such an equal foot with their vassals that I think I see a petty English exciseman receive more homage and respect than what was paid formerly…’. He depicted in turn a degradation of barons and burghs, judges and gentry, soldiers and sailors, tradesmen and farmers, before rising to a plangent climax: ‘But above all, my lord, I think I see our ancient mother Caledonia, like Caesar sitting in the midst of our senate, ruefully looking round her, covering herself with the royal garment, attending the final blow and breathing out her last with et tu quoque mi fili.’… Belhaven then burst out ‘Good God! Is this an entire surrender?’. He asked for time to shed a silent tear. After a pause, while the house chatted through his stagey gesture, he resumed in a less emotional tone, arguing that it was folly to agree to the Union before discussing all the articles and moving that the house should begin with the fourth, on free trade. Christopher A Whatley, on how the Act of Security for the Church helped the case for union, from The Scots and the Union, p306–7: By passing the separate act to secure the Church of Scotland as by law established after the union, the court hoped to take at least some of the steam out of the extra-parliamentary opposition. Government politicians both north and south of the border reckoned that such a step was crucial if the union was SECONDARY SOURCES to succeed in Scotland. Although Stair was convinced that ‘from this day forwards [12 November] the ferment will abate’, it was not enough for Belhaven – now leading a protest in Parliament against the English sacramental test – nor for those Presbyterians who were unwilling to reach any accommodation with England. But the act served its purpose. Paul Henderson Scott, on the Squadrone Volante’s hold on the balance of power during the period before and during the debate, from The Union of 1707: Why and How, p59: Seafield was particularly pleased by the recruitment of the Squadrone Volante, the group including Roxburgh, Tweeddale, Rothes, Baillie of Jerviswoode and others who had previously supported Hamilton and Fletcher. There is a hint in one of Mar’s letters that they had b een won over by a promise that they would be involved in the distribution of the Equivalent, a promise that was not kept. For months the group in their letters agonised over the situation, but as early as 15th December 1705 Roxburgh wrote to Baillie: ‘If Union fails, war will never be avoided; and for my part the more I think of the Union, the more I like it, seeing no security anywhere else’. He had made the same point about the danger of war on 26th December 1704: ‘I am thoroughly convinced that if we do not go into the Succession, or a Union, very soon, Conquest will certainly be, upon the first Peace’. By this he evidently meant as soon as the English armies were free from war in Europe. Douglas Watt, on the importance of the Equivalent to the passing o f the Act of Union, from The Price of Scotland: Darien, Union and the Wealth of Nations, p231: The identity of those who were to benefit from the Equivalent was vital and influenced support for the treaty in the Scottish parliament. The order of payment was a matter of some debate and was not finalised until 25 March 1707 by the ‘Act concerning the Publick Debts’. This provided a detailed breakdown of the beneficiaries: firstly those who lost out from the recoinage; secondly, and most significantly, £232,884 5s 2/3d for the shareholders and creditors of the Company; thirdly a subsidy of £2,000 per annum for seven years to the wool industry; fourthly an unspecified amount to the commissioners who had negotiated Union; and finally the military and civil lists (the public debts of Scotland). What was important, however, for securing the passage of the treaty, was expectation rather than payment. 16 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 SECONDARY SOURCES Christopher A Whatley, on the importance of the Squadrone Volante to the government’s victory in the debate on the Act of Union, from The Scots and the Union, p298: For an absolute majority in a Parliament in which 227 men sat, the court required at least 115 votes to be comfortable. Ministers however could only muster around one hundred, the confederated opposition a dozen or so fewer. This comprised the Hamilton-led Country party, the hard-core of which was provided by Fletcher’s fifteen or perhaps constitutional reformers – persistent and tenacious critics of the court – some nineteen Jacobites, and a group of resolutely anti-union nobles at the head of which was the earl of Errol. With around twenty-five squadrone MPs, however, the government could carry the union, and it did. Squadrone votes proved critical in securing approval for several of the articles which, had they been defeated, would have brought the union process to a shuddering halt. Paul Henderson Scott, on the role of the Duke of Hamilton during the debate period, from The Union of 1707: Why and How, p41: It seems almost incredible that anyone would be capable for two sessions of Parliament to appear both as the passionate advocate of the cause of independence and also as the man who undermined it on four decisive occasions. Perhaps he was torn between his convictions and self -interest. Apart from the implied threat to his English estates, he had other personal interests. If Scotland decided on a separate succession he had a claim to the throne because of his Stewart ancestry. If not, his interest lay in preserving good relations with Queen Anne. In this he seems to have succeeded. After the Union, he was given a British peerage as Duke of Brandon in September 1710, and in 1712 Queen Anne appointed him as Ambassador to France and gave him the Order of the Garter. He was killed in a duel in London in the same year. Michael Fry, on the end of the Treaty of Union debate, from The Union: England, Scotland and the Treaty of 1707, p290: The battle had been lost and won. On January 16, the Treaty of Union and Act of Security for the Kirk were ratified in tandem as the Scottish Act of Union by 110 votes to 67. Since the first major division in November, the government’s tally had held steady, while the opposition’s hand had shrunk. It was probably Hamilton that commented: ‘And so the darkest day in Scotland’s history has finally arrived. The point of no return has been reached, and nothing is left to us of Scotland’s sovereignty, nor her honour or dignity or name.’ Lockhart could not bring himself even to be there. Queensberry touched the Act with the sceptre straight after the vote. SECONDARY SOURCES Michael Lynch, on whether the passing of the Act of Union was part of a historical process, from Scotland: A New History, p316: The only hint of a broader British identity of interests in 1689 had come from the Scottish parliament which suggested a ‘union of parliaments and trade’. The point to realise is that the Scots had offered some such union in 1606 and 1641; 1689 would be the last time they did so. The constitutional safeguards demanded of William in 1689–90 were framed as the Scottish solution to what was perceived as a distinctly Scottish problem and, as a result, the two countries were set on different political courses throughout the 1690s, which mean that they were probably further apart in 1700 than at any point since 1660. The Union of 1707 completed the regal union of 1603 only in a very limited sense. The most determined unionists in both 1603 and 1707, it is true, were the monarchs themselves, but the amalgamation of the two imperial crowns in 1707 was a reflection of how much monarchy itself had changed over the course of the century. The Union of 1603 had been grounded on the royal prerogative; the Treaty of 1706 –7 made no mention of the prerogative. Constitutionally, very little was amalgamated in 1707, for the Treaty had scarcely anything to say about the governing of Scotland. That amalgamation would take place; but as part of the creeping frontier unionism set in train after 1707; by May 1708 the hidden agenda had already claimed the scalp of the Scottish privy council. J D Mackie, on what Scotland obtained from the Act of Union, from A History of Scotland, p263: The Act of Union was a remarkable achievement. It made two countries one and yet, by deliberately preserving the Church, the Law, the Judicial System, and some of the characteristics of the smaller kingdom, it ensured that Scotland should preserve the definite nationality which she had won for herself and had preserved for so long. It realised some of the desires of both countries. To England it gave security, in the face of French hostility, for the Hanoverian succession and for the constitutional settlement of the Revolution; to Scotland it gave a guarantee of her Revolution Settlement in Church and State, and an opportunity for economic development which was sorely needed. A I Macinnes, on the major factors contributing to the success of English efforts to secure Union in 1707, from Union and Empire: The Making of the United Kingdom in 1707, p264: The making of the United Kingdom in 1707 was the product of power, control and negotiation. England had the military power to coerce and the fiscal power to persuade. The English ministry was intent on controlling through political incorporation what had become a rogue state in terms of commercial 18 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 SECONDARY SOURCES exchange. Likewise Queen Anne was intent on terminating what she conceived to be the rogue behaviour of the Scottish Estates in seeking to limit the prerogative powers of the crown. In return for union, Scottish manpower, enterprise and ultimately Scottish intellectual endeavour were harnessed in the service of Empire. The Union gave Scotland free access to the largest commercial market then on offer. The unrestricted movement of capital and skilled labour within that market stimulated and fructified native entrepreneurship both domestically and imperially. Paul Henderson Scott, on why the Act of Union was passed, from The Union of 1707: Why and How, p84: The English Government behaved like skilful but ruthless confidence tricksters and many Scottish Members of Parli ament give the impression that they were too naïve to see through the deception. On the other hand, the Addresses from the public at large show that there was a widespread understanding of the situation. Probably Clerk was right. Supporters of the Union in the Scottish parliament were probably more understanding and sophisticated than they appeared. What was on offer was preferable to an invasion and its consequences. So why not opt for the lesser evil? Issue 4: Effects of Union to 1740 Michael Fry, on the immediate reaction of merchants to the Act of Union, from The Union: England, Scotland and the Treaty of 1707 , p305: Not only the noblemen and lairds of Scotland felt unhappy at the consequences of the Union. So, for example, did the merchants who had hoped to do well out of it. And they did do well right at the outset, or rather during the gap between the parliamentary passage of the Union early in 1707 and its entry into force on May1. During those few months they made a quick killing from a rush of imports – wine, tobacco and other luxuries on which Scottish tariffs were low, all to be re-exported to England once her higher tariffs had been erected right round the new United Kingdom. Politicians at Westminster felt furious but had no remedy. They soon got their own back. Paul Henderson Scott, on how Queensberry was greeted in Scotland and England after the Act of Union had been passed, from The Union of 1707: Why and How, p66: There was the same contrast between the two countries in their reactions when the Treaty came into force. Queensberry had been stoned by the crowd in Edinburgh; but, when his work as Commissioner was complete, he made a triumphal progress through England to London in April 1707. Clerk, who SECONDARY SOURCES accompanied him, says that in all the English cities he passed through, he was received ‘with great pomp and solemnity; and the joyful acclamations of all the people’. Christopher A Whatley, on calls for repeal of the Act of Union, from The Scots and the Union, p325: We can begin to understand why, in the first two or three post-union decades, a substantial body of opinion in Scotland was of the view that the union should be repealed; for the first seven or eight years after 1707 this pressure was intense, both in the country and – less so – among Scotland’s Westminster representatives, the forty-five MPs and the sixteen representative peers. But in Scotland the demand that the union be broken was given a sharper edge by the Jacobites, whom it reinvigorated after the collapse in morale that had caused them to drift away from Edinburgh at the beginning of 1707. The disappearance of the Scottish Parliament and with it the links protestors outside had had with the Country party within, had left a vacant space within the body politic in Scotland, which the Jacobites had begun to fill even prior to 1 May 1707, when they had called for Louis XIV to seize the moment and land French forces in Scotland. The opportunity to position themselves at the head of the popular opposition there was to the union they grasped eagerly, supported by a welter of publications that now celebrated the once-defiled house of Stuart, and emphasised its legitimacy. Douglas Watt, on the historical significance of the Equivalent in the context of Scotland’s relationship with England since the Union, from The Price of Scotland: Darien, Union and the Wealth of Nations , pxvii: On 5 August 1707 a dozen wagons carrying a large quantity of money arrived in Edinburgh guarded by 120 Scots dragoons. A mob was waiting to hurl abuse as they trundled up to the castle to deposit their load and, on the way back to down, to pelt them with stones. This was how the infamous ‘Equivalent’ was welcomed to Scotland; the huge lump sum paid to the Scots by the English government as part of the Treaty of Union of 1707; a bribe, bonanza or bail-out depending on your point of view. The stoning of those who delivered the Equivalent reflected the acrimonious divisions within the Scottish body politic, and is perhaps symbolic of the way in which Scots have viewed the Union ever since; repelled by their surrender of their national sovereignty, but at the same time willing to take the cash and opportunities it offers. 20 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 SECONDARY SOURCES Michael Lynch, on the much-debated economic effects of Union, from Scotland: A New History, p323: The first years of Union brought new taxes but no new concessions, and it exposed vulnerable industries such as paper -making and woollen cloth manufacture to the chill wind of English competition. In 1711 new duties were imposed on exported linen and salt, in 1713 came the first extension of duties on malt, and in 1715 printed linens were also subjected to duty. The real effects of these measures could be and have been debated at length – the linen industry was forced into a shake -out of its practices and quality control which by the 1740s was beginning to yield worthwhile results; the decline in export of salt and an increasing reliance on domestic demand were both patterns which had begun before 1707. J D Mackie, on the possibility of disunion and the attempted repeal of the Act of Union after the constitutional and ecclesiastical grievances during the period 1707–13, from A History of Scotland, p268: The outcome of these accumulated grievances was the introduction of a motion in the House of Lords (1713) to rescind the Act of Union; this was supported by all the Scottish members, Whigs and Tories alike, and it was defeated in the Lords only narrowly and by the votes of proxies. It has been doubted if the Scots meant to force the issue; anyhow the necessity disappeared. On the death of Anne (1 August 1714), the Whigs, amongst whom Argyll was conspicuous, acted with resolution. To the surprise of the Jacobites, George I ascended the throne ‘amid acclamation’ and with the establishment of a mainly Whig ministry the danger to the ‘Revolution Settlement’ seemed to fade away. But it did not disappear altogether. Discontent in Scotland was both wide and deep and, in both England and Scotland alike, there was still the instinctive feeling that as long as th e ‘legitimate’ monarch was extant there was no hope of permanent peace. For three decades it seemed possible that the exiled dynasty might return. Christopher A Whatley, on opposition to the malt tax, from The Scots and the Union, p345: The pinnacle of post-union disorder was the rioting that greeted yet another proposal, in 1725, to raise the malt tax in Scotland. Walpole, effectively prime minister, had been under pressure from English MPs hostile to the Scots to raise more revenue from Scotland – £20,000 is what the treasury wanted. Linked was a proposal to remove the bounty on grain exports. There was an explosive, two-stage reaction. The first was a flurry of letters, petitions and pamphleteering, directed against the removal of the bounty as an intolerable infringement of the union principle of equity between the two nations, and reiterating the Scots’ inability to pay the malt tax... The second SECONDARY SOURCES phase of protest, a wave of riots, [commenced] in Hamilton on 23 June, the day collection of the new tax was to commence; these then spread to Glasgow, scene of the infamous Shawfield Riot, during which the house of the city’s MP, Daniel Campbell, was broken into and ravaged by a mob. Alexander Murdoch, on the problems facing the Walpole administration in Scotland, from T M Devine, Scotland and the Union: 1707–2007, p83: Nor did the Union experience serious problems only from Jacobite rebellion and subsequent British military intervention. During the long period of peace from post-1716 to 1739 presided over by Sir Robert Walpole as first minister to both George I and George II at Westminster, governing Scotland became increasingly more, rather than less, problematic. It has been suggested that this was due at least in part to Walpole’s inclination to trust to the Duke of Argyll to preserve order in Scotland through the enormous extent of his property, power and consequent influence there. He embarked on this policy after major Scottish resistance to tax collection reached something like open rebellion in 1725 with the so-called Shawfield riots in Glasgow and related disturbances in Edinburgh. T C Smout, on the relationship between the clan Campbell and the ultimate failures of Jacobite risings after 1707, from A History of the Scottish People, 1560–1830, p206: From the point of view of London, the main problem after the Union was the Jacobites, whose strongholds in the hills beyond the Tay might yet have proved the Achilles heel of the whole British Protestant establishment. The civil war of 1689, the two major Highland risings in 1715 and 1745, and two other abortive attempts in 1708 and 1719, seemed to show their fears were justified. On the other hand, neither the English ministry nor the Pretenders ever understood the extent to which the rebellions were pr ovoked not by loyalty to the Stewart cause but by hatred of the great clan Campbell, whose steady aggrandisement at the expense of smaller, weaker and less politically minded clans was a cardinal objective of Government policy: after all, the political managers of Scotland from 1725 to 1761 were successive Dukes of Argyll, and the idea of using this clan to hold down and civilise its neighbours had been part of royal policy since the days of James VI. This was the reason why the rebellions in 1715 and 1745 produced so brilliant an explosion in the north and so little effect in the south: Lowlanders had no special reason to hate the Campbells or to love the Stewarts, and they were certainly not inclined to rise spontaneously against the Westminster government at the beck of a Catholic prince. 22 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 SECONDARY SOURCES J D Mackie, on the attempted rising of 1708, from A History of Scotland, pp269–70: Anxious to avenge Marlborough’s victories and aware that Scotland was ill defended, Louis XIV launched in March 1708 a powerful fleet c onveying 6,000 men, and graced by the presence of [the Old Pretender]. This was destined for the Firth of Forth, but bad weather, faulty navigation, a marked lack of enthusiasm amongst the French soldiers and sailors, and the arrival of English ships prevented the invaders from making any landing. Yet in England and Scotland alike, it was felt that a very real danger had been averted by fortune alone. T C Smout, on the rise of improvers in the 18th century and the inclination of landowners to recruit English farm managers, from A History of the Scottish People, 1560–1830, p274: Some [landowners] were more generous than Cockburn, and financed the division of the runrig, the running up of enclosure walls and hedges and the building of new steadings from their own pocket: others financed them indirectly by reductions of rent for a period of five or ten years after enclosure. Nor did landowners leave the tenants once the layout of the farms had been changed: a trickle of skilled Englishmen arrived throughout th e century at the invitation of the nobility and gentry to manage their own farms and to teach the sons of local farmers better ways; the landowner himself continued to pour out upon his dependents a stream of gratuitous advice. J G Pittendrigh, on the reality behind the ‘payment’ of the Equivalent, from Paul Henderson Scott, The Union of 1707: Why and How, p76: As a footnote to history the Equivalent Debentures were eventually redeemed in 1850. From an English point of view they had effectively received a 143 years interest-free loan from the Scots of £248,000. At the end of the day England had purchased control over Scotland, its people, mineral rights, fishing and other natural assets for cash payments of only £150,000, equal to 3 shillings for every man, woman and child in Scotland at the time. At the same time they had also eliminated potential competition from the Scottish African and Indian Company. With this modest sum they had pulled off a tremendous coup for which it would be hard to find a histori cal parallel. In exchange the Scots received the equivalent of an 8% share in the ‘British’ decision-making process, the legal right to trade with the American colonies (which they had been doing in any event ‘illegally’) and the right of access to English markets (as, of course, the English also had to the Scots). And the Scots took on the obligation of contributing manpower and money to the many wars entered into by the Anglo-British state, including against France, The Netherlands and other countries that Scotland formerly never had any SECONDARY SOURCES quarrel with. They also took on a share of England’s debts whilst the English were absolved from any further obligation towards settling Scottish debts. Michael Lynch, on the work of General Wade as part of the governme nt’s attempts to control the Highlands between 1715 and 1745, from Scotland: A New History, p332: It was on this basis that General George Wade, an Anglo -Irish soldier with a nose for ferreting out Jacobite sympathisers, was appointed commander in Scotland in 1725. Between 1726 and 1737 Wade organised the building of over 250 miles of military roads deep into the western and central Highlands. In 1725 there were only four isolated government garrisons – at Inverlochy, Ruthven near Kingussie, Berbera in Glenelg and at Killiechiumen, later to become Fort Augustus. Wade’s road system was designed to create a cordon sanitaire along the line of the Great Glen, reinforced by a naval galley on Loch Ness. It was the Cromwellian system of the 1650s writ large, with arteries linking it to the south, including a road from Perth via Dunkeld to Inverness. T C Smout, on disorder in Edinburgh, the role of ‘caddies’ during mob incidents, and those involved in the Porteous Riots, from A History of the Scottish People, 1560–1830, p345: Riots were another matter. The town guard certainly had no stomach to face a mob, while the Edinburgh ‘caddies’ (a brotherhood of unofficial guides who knew every address in town, and who were occasionally entrusted by the local authority with executing a council order) were likely to be first among the crowd if they thought popular justice was to be meted out. The composition of the town mob varied from time to time according to its objectives, but it often contained artisans and mechanics of a more middleclass than working-class character, while in 1736 there were well -grounded suspicions that quite prominent citizens as well as apprentices and journeymen took part in the capture and lynching of Captain Porteous. Christopher A Whatley, on the gradual benefits of union, from The Scots and the Union, p358: Even so, for all that the union created difficulties for the Scots, it also made its mark in more favourable ways too, which sometimes only appear with forensic interrogation of the numbers. Thus, while Trinity House of Leith data show a rise in voyages overseas from 1704, after the union more of these involved passages to and from Spain and Portugal – England’s ally; at Aberdeen and Dundee coastal shipping increased sharply after 1707 and, i n the last-named, within five years of the union England had replaced Norway as the burgh’s main trading partner, with timber imports dropping to zero as a 24 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 SECONDARY SOURCES result of restrictions imposed by British commercial policy. Perhaps more slowly, the same thing happened at Aberdeen, where by 1735 London had replaced Veere as the main supplier of manufactured goods. T C Smout, on the surprising similarities which emerged after Union between the Church of Scotland and the Church of England, from A History of the Scottish People, 1560–1830, p213: It was only to be expected that in politics and government England and Scotland would grow more alike after 1707. The same phenomenon in their churches is much more surprising. The settlement of 1690, by abolishing episcopal rule, and the Union of 1707, by confirming Presbyterianism as the established polity for Scotland even in a United Kingdom, seemed to open and to fix in perpetuity the gulf between the Church of Scotland and the Church of England. Indeed, in matters of c hurch government, order and theology the churches remained ossified at opposite poles of thought. The drawing together came in the subtler (but nonetheless real and vital) spheres of social outlook and position, in which the Scottish church came to occupy a very similar standpoint to that of the English church. By 1790 neither Presbyterian nor Anglican leaders had any time for puritanism, both believed that the social order was already organised in a way highly satisfactorily to God and both assumed the Lord to be moderate in His religious views as they were themselves. Christopher A Whatley, on the historical perspective of the Union of 1707, from The Scots and the Union, p370: For others – most – [the Union] offered entry to and the shelter of an empire the expansion and defence of which the Scots themselves were to contribute to and with their labour and lives. Left alone and with England’s ascendancy within the union unchallenged, it is likely that it would have imploded within a few years of its making. Where Scotland would have been in such circumstances is hard to say, and takes us into the realms of speculative history. By insisting that the union should work to the advantage of Scotland, in ways that were only vaguely envisaged by those who had soug ht periodically to achieve it from the time of the Revolution of 1688 –9, union provided Scots with opportunities for personal and national achievement that had been thwarted during the later stages of the union of the crowns, and by the stifling effects on commercial ambition of muscular mercantilism. It was a framework that, with countless adjustments, has lasted for three centuries. Those Scots who signed the addresses delivered to William of Orange at Whitehall late in 1688 that called for ‘ane intire an d perpetuall union betwixt the two kingdomes’, would have been amazed and, no doubt, greatly gratified. CURRICULUM FOR EXCELLENCE IDEAS Curriculum for Excellence ideas Blockbusters This is a game which can help revision and aid in the preparation for factual tests. Classes will hopefully enjoy the competitive element of the quiz -based lesson, and the answers to the questions may be easier to recall after playing the game. Method: Have the 25-hexagon blockbusters grid on the board before class come into room. Use any of the references in the biographical dictionary or glossary of terms or timeline to formulate answers. Have the answers on question sheet, in alphabetical order so they are easy to find when participants select a question. Letters represent the answers. One capital letter represents a one-word answer. Two capital letters represent a two-word answer. A capital letter and a small letter which follows it represent the first two letters in a one-word answer. A capital letter followed by a hyphen and a small letter represe nt the first and last letters of a one-word answer. Names of two teams should be written in separate colours on the board (eg Country party and Court party, or commissioners and MPs) ready to have scores written below them as they accumulate. Split class into two teams. Explain the rules. Read out questions, choosing an answer hexagon in the centre of the grid to start with. Each team that gets an answer right gets the number of points equal to the number of words in the answer. They also get the answer hex agon circled in their colour. The member of the team who got the answer correct can choose the next answer hexagon. If a team manages to get across the grid, from side to side or top to bottom, in a route of only their own colour, they get an extra five po ints. 26 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 CURRICULUM FOR EXCELLENCE IDEAS This means that tactically, teams will try to ask for questions that will create a line. The last question asked is always worth ten points. The teacher has the discretion to award bonus points for more difficult answers in order to try and maintain parity between the teams to keep the quiz going down to the last question! Participants should be warned – no triumphalism when their team gets an answer correct – marks will be deducted at the teacher’s discretion for this! Sample set of answers: AAPAW – Act anent Peace and War AFOS – Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun CG – Captain Green DOA – Duke of Argyll DS – Darien scheme EE – Ebenezer Erskine EOG – Earl of Glasgow Ep – Episcopalian Eq – Equivalent GC – Greenshields case GLOC – George Lockhart of Carnwath IY – Ill Years JTSAF – James VI and I LB – Lord Belhaven LTF – Louis XIV MOS – Master of Stair MOT – Marquis of Tweeddale M – Malt NA – Navigation Acts PR – Porteous riots QA – Queen Anne RS – Revolution settlement SRW – Sir Robert Walpole S – Stuart SV – Squadrone Volante (tiebreaker – WP – William Paterson) CURRICULUM FOR EXCELLENCE IDEAS Board games challenge This is an enterprise activity which could take three or four lessons to follow through, and could be tied in with other historical issues covered in the year, ie Paper 1 topics. Materials should be available, such as coloured pens and pencils, paper, cardboard, scissors, sellotape, string, etc. Students should work in groups of three or four. In the first lesson each group should be given a topic based on which they have to devise a board game. The Treaty of Union should be one, with Paper 1 topics also being used. If the Treaty of Union is the only topic being used, it could be split into the four issues. Each group should think of a popular board game, eg Monopoly, snake s and ladders, trump cards, etc. They should then adapt the game to include a requirement for knowledge of the historical topic in order to make progress and win the game. Students could start work on their games before the end of the first lesson if time allows. If any extra materials are required by groups, they should tell the teacher during the first lesson and the teacher should try and get these for the second lesson. In the next two or three lessons the students should complete their board games and then play each others’ games. 28 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 ASSESSMENT IS FOR LEARNING IDEAS Assessment is for Learning ideas Cooperative learning activities Students can benefit from cooperative learning techniques by conducting research on a particular part of the course and then teaching the rest of the class about what they have learned. This kind of activity can take a couple of lessons to complete. An example of this could be separating the class into small groups of about three or four and giving each group a target of teaching the rest of the class three or four historical facts about, say, a particular person involved in Treaty of Union negotiations, or a prominent figure during the Act of Union debate. Or they could research facts about a particular event or development, eg the Greenshields Case or the execution of Captain Green. Each group would have to research using notes, books or the internet (book a computer room) and then devise a way of teaching the results of their research to the rest of the class in the next lesson, using Powerpoint, or flashcards, or the board. The teacher should check in the first lesson that the three facts each group have found out are correct. The teacher should offer assistance in preparing material, for example having photocopies made if required. This kind of experience gives the students something to focus on, which helps to train them for times of revision or further research. In the second lesson the whole class should learn a number of new facts in an interesting way, which should be memorable as it is set asi de from ‘normal’ classroom practice. ASSESSMENT IS FOR LEARNING IDEAS Peer assessment Once students are familiar with the criteria for awarding marks to answers to source questions, they are in a position to carry out peer -assessment. A source question should be presented to the class . The teacher should go over the source and discuss methods of answering, with students making notes if they want. Then each student should write an answer to the question. They should exchange answers with each other and the teacher should go over the co rrect way of answering, and students should decide what mark to award the answer in front of them. The exercise should be repeated with a totally unseen source question. Students could either mark a classmate’s answer in the lesson or it could be taken home to mark, with part of the homework to be making an appropriate constructive comment under the answer. 30 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 WEBSITE LINKS Website links www.activehistory.co.uk This site comes recommended by the Times Educational Suppl ement and has innovative suggestions for interactive and classroom activities to aid the learning of history. www.alba.org.uk This is the website of the Scottish Politics Research Unit and Alba Publishing. The site has recently included a useful set of detailed timelines covering many periods of Scottish political history. www.bbc.co.uk/scotland/history The BBC contains a very useful timeline on British history as well as links to specialised sites, and will soon have interactive maps. www.britannica.com The website of Encyclopedia Britannica, this contains many useful articles on the Act of Union and related topics. www.channel4.com/history/microsites/H/history/browse/1700-1800.html This section of the Channel 4 history website contains a section ‘The Scots Detective’ which covers the whole of Scottish history and has factual information, activities for schools and links to other websites. www.history.ac.uk The Institute of Historical Research exists to provide resources for those wishing to teach or study history. Its site contains links to other history websites and reviews of books and journal articles on the Act of Union period. www.historytoday.com This website of the History Today magazine contains an archive of articles published on all topics including Scottish history, as well as links to sites of other institutions which deal in Scottish history. www.ltscotland.org.uk Learning and Teaching Scotland provides many other useful resources on the period and on study skills in general or specific to Higher History. WEBSITE LINKS www.nas.gov.uk The National Archives of Scotland recently carried out a lot of work on the Treaty of Union period. The site contains digitised images o f historical documents, as well as information on the records of the Scottish Parliament. www.nls.uk/scotlandspages/timeline.html This is on the site of the National Library of Scotland. The intera ctive timeline allows pop-ups of extracts from the writings of Scots involved in significant national events, including extracts from the memoirs of George Lockhart of Carnwath on the Treaty of Union. www.nationalgalleries.org This is the site of the National Gallery of Scotland and the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, among others. There are excellent images of portraits of notable people involved in the period surrounding the Act of Union, as well as accurate biographical details. www.parliament.uk The Parliament website contains good references to the Act of Union and its position in British history. www.schoolhistory.co.uk Although limited in content about the Act of Union, this site does have some useful references as well as lots of ideas about activities to do in history classes which would tie in with A Curriculum for Excellence and Assessment is for Learning www.scottishcatholicarchives.org.uk The Scottish Catholic Archives website contains information about useful education material that can be obtained from its premises in Edinburgh. www.rps.ac.uk The Records of the Parliament of Scotland have been collated at the University of St Andrews; they cover the period 1235 to 1707. This is an excellent resource for analysing primary material. www.scottishscreen.com Scottish Screen holds archives of film of all types, and information about new and imminent film or television productions that may be relevant to History. It also contains advice about how to utilise Moving Image in Education (MIE) techniques in schools, including history classes. 32 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 WEBSITE LINKS www.sqa.org.uk The Scottish Qualifications Authority website contains information for teachers and students, and includes all the Higher History descriptors as well as past papers, mark schemes and advice for best practice. www.wikipedia.org Wikipedia contains many articles that have been checked by experts and it is a useful tool for beginning a search for more detailed information on events and people from the period. TEACHING PLAN Teaching plan Ideally Paper 2 Treaty of Union should be taught in a 40 –hour period. With timetable restrictions, variations between schools on lesson lengths and opportunities for double-periods, it is unrealistic to present a prescriptive plan. However, below is a suggestion as to the allocation of time to different parts of the course, with an average of 45 minutes teaching time being considered appropriate for ‘1 lesson’. Explanation of Paper 2 issues 1 lesson Background 1 lesson Worsening relations with England Revolution of 1688–9 King William Darien Scheme English and Scottish legislation Other issues 2 1 2 1 1 Source practice 2 lessons Arguments for and against union with England Arguments for union Arguments against union 2 lessons 2 lessons Source practice 2 lessons The passing of the Act of Union Position of England Arguments for federal union Arguments for incorporating union Debate on the Act of Union Reasons for passing the Act of Union 1 1 1 3 2 Source practice 2 lessons 34 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 lessons lesson lessons lesson lesson lesson lesson lesson lessons lessons TEACHING PLAN Effects of union to 1740 Political Economic Social Religious Jacobites 1 1 1 1 1 Source practice 2 lessons Perspective 1 lesson Source practice 5 lessons lesson lesson lesson lesson lesson EXTENDED ESSSAY Extended essay Candidates are permitted to write their extended essay on the Paper 2 option. Below is a guide to suggested essay titles and possible plans for writing the essay. Essay titles Evaluation/assessment style questions: How far did the Treaty of Union bring about economic benefits for Scotland? To what extent can it be argued that the arguments against union with England were mainly religious in nature? Isolated factor style questions: How important was the Darien Scheme in worsening relations between Scotland and England between 1688 and 1706? To what extent did financial issues contribute to the passing of the Act of Union in Scotland? 36 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 EXTENDED ESSAY Sample plans – evaluation/assessment How far were the effects of the Treaty of Union in Scotland mainly economic? Introduction: Context – background information on Treaty of Union, economic arguments for and against union, outline of period 1707 –1740. Factors – economic, political, social, religious, role of Jacobites. Line of argument – economic effects felt, other effects also felt. Main body of essay: Economic effects – issues concerning the Equivalent, loss of textile markets to English competitors, unpopularity of Malt Tax, improvements in agricultural production, investment in Scotland, Royal Bank, Board for Fisheries and Manufactures. Political effects – office of Scottish Secretary, abolition of Scottish Privy Council, issue of Scots peers in House of Lords, Highland clans’ loyalty to either Hanoverian Succession or Jacobism, 1713 motion to repeal Act of Union, dominance of Whigs. Social effects – unpopularity of Union after 1707, issue of Scots law in House of Lords, confiscation of Jacobite land, social plight of the Highlands, new Scottish publications in the press, social disturbances across Scotland in 1720s and 30s, road-building and forts in Highlands. Religious effects – preservation of Presbyterian Church, challenge to Church of Scotland privileges by High Church Tories, Episcopalianism as an issue, Greenshields Case, Toleration Act, Patronage Act, Marrow Affair, formation of Associate Presbytery. Jacobites – continued Jacobite support, attempted French -led invasion of 1708, Rising of 1715, role of Earl of Mar, attempted Spanish -aided rising of 1719, reduced Jacobite resistance before failed Rising of 1745. Conclusion: Summary – definite economic impact of Union. Arguments – initial economic effect not felt by many, benefits gradually realised by 1730s, political effect more immediate resulting in moti on to repeal, social effects greatest in response to Jacobite issues and Malt Tax, religious effects seen in controversy after Greenshields case and later secession of some from Church of Scotland, Jacobites reacting to union with series of attempted risings. Judgement – economic impact part of wider set of linked effects of Union. EXTENDED ESSSAY Sample plans – isolated factor To what extent can it be argued that the arguments against union with England were mainly religious in nature? Introduction: Context – background information on Treaty of Union, relations between Scotland and England, arguments against union. Factors – religious, economic, political, social, succession. Line of argument – religious arguments existed, several others also existed. Main body of essay: Religious arguments – fear of English domination of religious affairs, fear of Anglicanism, fear of Episcopalianism, fear that Presbyterian Church would disappear. Economic arguments – increased tax burden, English trade would be favoured over Scots, Darien example cited, fears for rights of royal burghs, possible ruin of Scottish manufactures, loss of European trade to England. Political arguments – reduction in status of Scottish nobility, undermining of Claim of Right, dishonour of surrendering Scot tish independence, suppression of Scotland by English minority, fear of ‘Scotlandshire’. Social arguments – fears over Scots law, public opinion against union. Arguments relating to the succession – Hanoverian Succession would apply to Scotland, end of Stuart line, threats to Scottish identity. Conclusion: Summary – definite religious arguments against union. Arguments – some Presbyterians feared imposition of Anglicanism on Scotland, fear of economic collapse in Scotland due to English competition in trade, political suppression by England, social opinion against union, end of hopes for Stuart succession. Judgement – religious opposition part of wider set of linked arguments against union. 38 THE TREATY OF UNION (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009