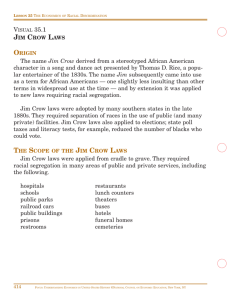

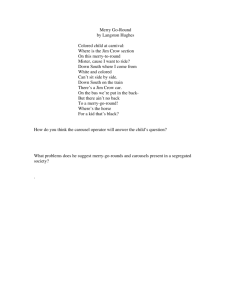

Chapter 5: The New Jim Crow

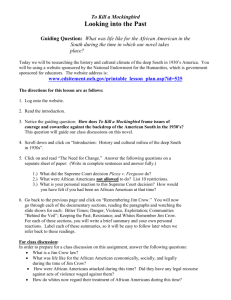

advertisement