FEDERAL INCmlE TAXATIO -- N L.

advertisement

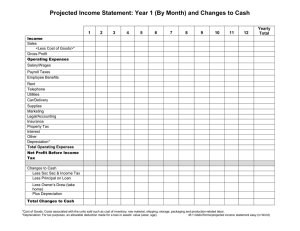

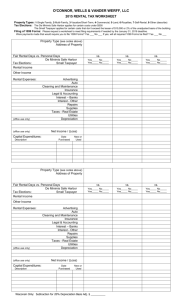

FEDERAL INCmlE TAXATION RESORT PROPERTY -- INVESTMENT OR RETREAT? WILLIAM L. THOMASON I. In 1956, petitioners, John R. and his wife Rosemary W. Carkhuff, purchased residential property on Sea Island, Georgia, an island which is operated as a pr ivately owned resort. The Sea Island Com- pany owns the only hotel on the island and has a Rental Department which is , the , exclusive rental agent for the petitioner's property and all other available rental property, comprising approximately onehalf of the houses on the island. The Sea Island Company regularly ' advertises in the various media and distributes pamphlets describing the services and facilities available. Most of the advertising mentions the availability of rental cottages, but none of the cottages, including petitioner's, are specifically mentioned except upon ' request from a prospective tennant. Petitioners have prepared a brochure describing their' cottage and such has been made available to interested • parties. Soon after purchase of the property petitioners listed their house with the Rental Department, but expressly reserved the months of . February, March, April, and October for their exclusive use. According to the findings of fact in the Tax Court Decision, 2tl TCM 377, there are two peak rental periods for the cottages at Sea Island -March through April and mid-June through August. As is readily apparent, petitioner's had their cottage reserved for two of these four and onehalf months. Following ,a Rental Department survey generated by the complaints of a tenant in the summer of the Petitioners. 1962 modest refurbishments were made by 2 During the years in question in this case, petitioner's reported substantial income from other sources, and on their income tax returns for the years 1962, 1963, and 1964 reported receipts from rental of ·their Sea Island cottage and claimed deductions for expenses and depreciation with respect thereto. The Commissioner, in his notice of deficiency disallowed petitioner's claimed "Rental Loss," with the explanation for each year that petitioners had not "established that the property was acquired or is operated with the reasonable expectation or purpose of realizing a profit, and because the property was acquired and is used primarily 1 for personal reasons." In holding for the Commissioner, the Court felt the disposition of the case depended upon whether the holding out of the property for • a trade or business rental purposes by the petitioners constituted or a holding of· property for the production of income within the pur2 view of sections 162 and 212 of the 1954 Internal Revenue Code. The Court· found no evidence of any intention ,of making a profit and inferred that the petitioner's only purpose was the recoupment of some ·of his costs in maintaining a personal residence not occupied for the entire year. Of significant relevance to the Court was the fact that the petitioners reserved the cottage for the·i r personal use for almost one-half of the peak rental season, and that they refused to air-condition the premises after being advised that this would substantially increase the desireability of their property. The Court further found that even if the petitioners had rented their property for the other one-half of the peak season, the return would not have been in an 3 amount equal to depreciation, taxes and the cost of operation, although it would have returned an amount in excess of direct operating expenses. For this reason the Court felt the property was n·o t held as an investment • . Noting that the petitioners could use the property if not rented and upon prior notice to the Rental Department, the Court concluded, based upon the lack of evidence, that the petitioners not only might have made personal use of the property during the periods it was offered for rent but that they had to some extent done so. Not holding that such property could not under any circumstances be held for investment, the Court stated: "While we recognize that homes of the type of petitioners' may be held for production of income, the evidence in this case indicates that there was no bona fide intention by petitioners to use their property primarily for income production pur~oses except for the period it was actually rented."j The Court entered decision for the Commissioner noting that not all the deductions claimed by petitioners were disallowed with respect • to their Sea Island property, but only the losses resulting from the excess of the deductions over income. On appeal, John R. Carkhuff v. Commissioner, 425 F.2d 1400, 28 TCM 375, the taxpayers concentrated their argument on the proposition that their· Sea Island property was "held for the production of income." They argued that the finding by the Tax Court that the property was listed as being available for rent, and was rented for some time, compels the conclusion that it was held for the production of income. The Court found this allegation to be inconsistent with 4 , Treas~y 4 Reg. 1.2l2.l(c). The Court went on to say that the taxpayer failed to sustain the burden of proof in view of the magnitude of the losses and the taxpayer's financial situation and taxpayer's reservation of the residence during almost one-half of the peak season, even though the taxpayer's listed the property as , available for rent and made improvements to make it more attractive for rental purposes. "The Conmissioner disallowed the deductions , because the taxpayers had not established that the property was acquired or '(was) operated with the reasonable expectation or purpose of realizing a profit, and because the property was acquired and (was) used primarily for personal reasons." 5 The Court held that the taxpayers must demonstrate that they , had a profit seeking motive in holding their Sea Island property. The Court stated that it had been recogni~ed in other opinions that the absence of a profit is not determinative, but the operation must be of such nature that in good faith the taxpayer could expect a profit. It was noted that the Commissioner concedes that the taxpayers can make a dual use of property and that an allocation of the expenses and depreciation is permissible to that part of its use which relates to earning income or making a profit. But, as the Court pointed out, the rental effort in this case ,was not sufficient, standing alone, to sustain the taxpayer's burden. "The making of repairs and improvements does not necessarily demonstrate a rental intent and assuredly does not compel the conclusion that a profit 6 motive was present." Finally, in affirming the decision of the Tax Court, the Court here pointed out that, "it is noteworthy that of four and one-half months of peak rental periods, taXpayers 5 reserved the cottage f or their personal use for two of those months,. an action not entirely consiste nt with apr. ·f i' making motive." To date this opinion has not been appealed . 7 In light of this, several things should be l)ointed out for pers <.'I<:; interested in investing in some similar resort property: (1) this was a r~sidence at a privately owned resort; (2) the rentals were exclusively handled through a common agent, the resort owner, and the resort was advertised, · but not each individual cottage; (3) the taxpayers here did prepare a brochure on their property; (4) the taxpayers made at least some im- provements on the property to enhance the rentability of the cottage; (5) a dual purpose was allowed with allocation of expenses and de- preciation [although it should be noted here that ·the taxpayers used the property one-third of the year but attempted deductions on a 5~ basis ahd were denied -- but, there .was at least some evidence that the taxpayers may have used the property more than the reserved four months]; (6) the taxpayers reserved the cottage for their own use for four months per year, two months of which were a part of the , short four and one-half "peak season;" and finally, (7) the burden of proof was put on the taxpayers. All of these things should be con- sidered, and the obvious ones avoided if a taxpayer wishes to successfully deduct these expenses and depreciation in the future • . Since the decision in the abovementioned case came as somewhat of a surprise [to this writer at least], it would be Useful to take a look at the development of the cases in this area. In a 1949 deCision, Elsie B. Gale, v. ~., 13 TC 661, it was held that i t was the legislative intent to allow deductions of ordina;ry and necessary expenses incurred in the production of income 6 subject to Federal Income Taxation, whether or not the expense was incurred in connection with the taxpayer's trade or business. In Charle s S. Guggenbe imer v. ~., 2 TCM 814, the property in que stion was originally a residence, and although petitioner paid rent to the family partnership which owned it [of which he was a partner], the property was not otherwise rented, and the evide nce showed no . effort to rent it [although taxpayer's petition alleged he was willing to rent it.] The Court felt this was not sufficient to demonstrate a holding in the course of trade or business, or for the production of income. In the Court's language, "(T)here was no overt act in- dicating that the· production of income was the reason for holding the property." (p. 816) The Court went on to say, "... the prop- erty was used by petitioner as a residence and nothing else, and the . meagre and casual efforts, if they Can be ~ecognized as such, shown by the evidence, are not sufficient to give it a business character or show that it was held for the production of income." (p. 816) A 1935 case, Morgan v. ~., of losses under section 165(c)(2). 76 F.2d 390, dealt with deduction The question before the Court was "whether a residence abandoned as such and put into the hands of an agent 'to rent in whole or in part or to sell,' is devoted exclusively to the production of taxable rentals, ... " (p. 391) The Court felt not., as the owner did not remodel or recondition the house, or do anything that specially devoted it to rental purposes. (p. 391) This sounds similar to the "overt act" requirement of Guggenheimer. It should be noted also that the house involved here was .placed with the agent to rent 2! ~. 1 In S. Wise v. ~., 4 TCM 898, the taxpayer, who built a new residence into which he moved, was not allowed to deduct amounts spent for advertising his old home, putting up "for-sale" signs, etc., as nonbusiness expenses. Being only a minor point in this opinion, very little space was devoted to this particular question. In the language of the Court, "At one point the petitioner testified that .. the expenditures here in question were in connection with advertising and the upkeep of his property for sale or for rent." (p. 901) The Court obviously felt this was not sufficient proof and was too vague to indicate the property was held for the production of income or that these were expenses for the management, conservation, or maintenance thereof. In John M. Coulter, et al. v. Comm., 9 TCM 248, depreciation or maintenance expenses on the taxpayer's fo~mer residence were not deductible where there was no evidence that the residence was listed for rent or otherwise converted to business use. The Court pointed out here that "neither a listing for rent nor partial rental was , s bown here, to mark the conversion from personal to business use. " (p.250) In this ·case the plaintiffs demonstrated an intent to sell the property, and in fact· offered it for sale, but as above, never demonstrated an intent to use the property for income production. In the 1943 case of Mary L. Robinson v. Comm., 2 TC 305, a · former residential property was again involved, but the Revenue Act of 1942 had intervened. The Court found under the new statute, "(T )he property formerly constituting the home, under such language, no longer needed to be converted into business property as a prerequisite to allowable deductions." (p. 306) "If therefore the 8 property was ~ for the production of income, both maintenance expense and depreciation are deductible." (p. 3(6) As in the Morgan Case, supra, the house was listed for rent or sale with only negligable results. The court found "affirmative action" in the abandonment of the property as a residence, the listing . with the real estate firms, and the dilligent efforts of these firms. Speaking of Regulation 103 covering section 121 of the 1942 Act [now section 212], the Court said, "(T)hat there need not actually be income in order for the ·s tatute to apply, within the regulation, appears from the examples given of deductions allowable on ••• a building devoted to rental purposes, notwithstanding that there is actually no income therefrom; also where property is held for the production of income [investment], though not currently productive and there is no liklihood that the property will be sold· at a profit or be otherwise productive of income." (p. 308) "The statute does not require that the property be actually used for product ion of income, that is , be actually rented, but only ~ for that purpose." (p, 309) Under the Internal Revenue Code of 1954 we now have the benefit of sections 167 and 212, and the Regulations thereunder, to provide for the expenses referred to in the preceeding section. Section 212 was enacted to avoid the result reached in Higgins v. Comm., 41-1 USTC Para.9233, which refused to allow a taxpayer to deduct in- vestment expenses as a trade or business expense under the predecessor of Code sec. 162. The Court felt in this case that the taxpayer was not carrying on a trade or business. 9 Under these sections a taxpayer's investment property may take almost any form, and SO long as it is held for the purpose of pro- ducing income, expenses proximately related to income production, collecting proceeds of sale of the investment property and to its maintenance and conservation are deductible. "In the case of real estate investments, the issue is more often one of determining whether the property is held for the production of income, rather than the allowance of particular items. Once the preliminary question is re- solved in favor of the taxpayer, deduction of maintenance expenses 8 and depreciation follows almost automatically." Under TD 6279, 1957-2 ~~, ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred in the management, conservation, or maintenance of a building devoted to rental purposes are de ductible notwithstanding that there is ' actually no income therefro~ in the taxable year, and regardless of the manner in which, or the purpose for which, the property was acquired. Apparently at this point it is not even necessary to offer for rent if the property is held for investment • • In the 1967 decision of Smith v. Corom., 26 TCM 149, affd. 397 F .2d 804, the petitioners had permanently abandoned their old home and moved to a new one some distance away. During the next two years they expended approximately $5500 for maintenance and repair of the old property which had a cost basis of $60,940. The Court held that during the two years between abandonment and sale the property was "held for the production of income" as that phrase is used in sections 167(a)(2) and 212(2), I.R.C. 1954, ' thus entitling the petitioners to deductions in both taxable years for depreciation and for the amounts expended for maintenance and repair. The house was 10 sold for $62,500. which ~ ~ The Court here said (p. 151), "the property for ~ was held for the production or income." The . only evidence indicated to support such a decision was that the husba~d had just retired from a busine ss of real estate loans and in- vestment, and the judge feeling the question "was one of law" (p, 152) was persuaded that the property was held as an investment: The case of George S. Jephson v. Comm., 37 ETA 1117, held that a taxpayer who purchased a house for renting, listed it for rent with a broker and showed it to prospective tennants, but failed ~ ~ ~, was engaged in a business, and was entitled to deductions for care and maintenance expenses and depreciation on the property. In another case where a summer home was abandoned as a summer residence and was rented for the whole two month season of July and August the Tax Court allowed the deductioq of all the maintenance expenses incurred for the entire year on the theory that the property., being a summer residence had to be "kept up" for the entire 12 month period: Clarence B. Jones, 22 TC 407. It should be pointed out though that the question of whether a taxpayer is engaged in a trade or business, etc., is a question that must be decided anew each taxable year so that a decision for one taxable year is not res judicata for a prior or subsequent year. Helvering v. Prentice, 139 F.2d 691. "Similarly, a decision that a taxpayer is entitled to a deduction under section 212 of the 1954 Code for one taxable year is not determinative of his right to such a deduction for another year." Stoddard v. Comm., 141 F .2d 76. In light of all these deciSions, why the decision in the Carkhuff Case? As pointed out in that opinion, the Court seems to 11 be quite leary of high income bracket taxpayers seeking merely a tax dodge rather than a bona fide investment. As noted in the discussion of the opinion above, the Carkhuff's expenses, etc., were not deductible because a profit motive in making the cottage available for rent was not proved. Furthermore, there was no evidence that the property was held as an investment. It appears quite apparent from this case that the Courts will now be on the lookout for at least two things: lack of a profit seeking motive; a personal use by the taxpayer; and and other indicia of these two things. This is certainly not the first time that a profit seeking motive has been looked for. A whole series of cases can be found in which this factor was mentioned, the problem being that the Courts do not appear to be entirely sure just what a profit seeking motive is. As illustrative bf these cases, in the 1967 ~ecision of Schley v. Comm., 375 F.2d 747, a taxpayer with high gross income continually incurred substantial losses on a farm she owned. The Court, in holding for the Commissioner, stated that "evidence of businesslike management and efforts to improve efficiency of the farm operation does not by itself establish a profit motive." (p. 750) The holding of the case was that the "totality of the circumstances" must be looked to. In .this case, these circumstances, the substantial independent income, the magnitude of the losses [never less than ten thousand dollars per year] over a long period of time, the background of the petitioner, etc., all apparently weighed in favor of the Commissioner. [It should be pOinted out that there was a quite vigorous dissent in this case. ] In Transport Manufacturing and Equipment Co. v. Comm., __ F.2d __, 70-2 USTC Para. 9627, a corporation owned properties and rented these 12 properties to familie s which had substantial stock interests in t he corporation. Deductions for repair and maintenance costs ex- ceeding rents as ordinary and necessary business expenses were denied based upon a finding that the primary motive in owning the property was not for busine ss or investment purposes but was for the personal benefit of the families which occupie d the properties. Further cases often cited on this point are Mitchell v. Comm., 47 TC 120, F~2d 161. Lamont v. Comm., 339 F.2d 377, and Briley v. Comm., 298 These cases are strongly recommended for the reader needing a more expansive view of the 'reasoning on the matter. That expenses incurred in connection with property for personal use will be denied . deduction was held in the case of Bradley v. Comm., ltl4 F.2d 860, where the Court found that "the statute allowing depreciation of property used in the taxpayer's .trade or business does not authorize a deduction for depreciation of property devoted exclusively to personal use." (p. 863) [Remember that the Carkhuff Case did allow a "dual purpose" of the property, but apparently the evidence indicated , that the property was almost exclusively used by the taxpayers.] And, in International Trading Co. v. Comm., 275 F.2d 578 (1960), the Court held that a taxpayer cannot take depreciation deduciuns on property to the extent that it is devoted to personal purposes, whether those purposes are personal benefits to the shareholders of the corporate taxpayer or personal benefits to an individual who is a taxpayer. ( Thus, it appears that these two factors -- profit motive and nonpersonal use -- were of primary importance in the decision by the Carkhuff Court, and should instill caution in future investors. 13 II. With this general background in mind, it is now possible to examine a hypothetical transaction to determine just what expenses, depreciation, etc. would be allowable as deductions from the taxpayers' personal Income Tax. Assume that Mr. and Mrs. H.1. Bracket purchase a lakes.ide townhouse condominium at Paradise Lost, an exclusive private resort, located on beautiful Unfound "Lake -- an area quite popular with vacationers the year-round. The Brackets plan to use this property themselves approximately lafo of thetirne each year; and devote i t to rental purposes for the remaining 9afo of the year. an agreement with Paradise Lost, Inc., th~ They have signed owners of the resort area, to act as their sole agents in renting the property throughout the year and have reserved no particular period for their own exclusive use. [Having known the Carkhuffs for a number of years, the Brackets realize this to be the best idea. ] After extensive negotiations and conferences with the officials of Paradise Lost, the Brackets have selected a townhouse not completely finished and have suggested certain changes to be made in the completion which they think would further their chances of successfully renting their property. Also, after conferring with the officials, the Brackets have selected a 10cation suitable not only to their own particular preferences, but, based upon the suggestions of the officials, a location that would be equally beneficial as to their rental purposes. [It 14 should be noted at this point for possible future investors that the suggestions made by the owners could be completely self -serving, based upon their own profit making desires: ] Following selection, the Brackets were confronted with the following figures: the basic cost of the townhouse was $29,tl69.00 plus extras and alterations of $560.3tl for a total cost of $30,429.38 • . 8r:J1, of the purchase price was to be paid from the proceeds of an 25 year note with Friendly Finance --- $24,343.50. i11>, The balance was to be paid in cash. The Brackets estimated their Closing Costs and Pre-paid Expenses as follows: 1% loan origination fee Appraisal fee Credit Report Legal fees Recording fees • Survey Mortgagee's Title Policy 4r:J1, of Hazard Insurance premium for 3 years Tax Deposit $243.50 50.00 15·00 45.00 15.00 50.00 15·00 243,75 25·00 Total Closing Costs • The following Table shows the Monthly .E xpenses: Friendly Finance payment (principal & int.) Maintenance Fee [exterior, lawn] Water Electric Taxes Insurance Guards, Roads, etc. $187.91 20.tll 8.00 30.00 16.00 15·00 15.00 Total Monthly Expenses $292.72 Total Annual Expenses [$292.72 x 12] $3,512.64 The following Table indicates their estimated tax deductions: Fully deductible expenses: 15 Interest [year 1] Taxes [year 1] $1,930.00 192.00 Total per year $2,122.00 Partially Deductible [90% - time offered for rent]: Depreciation [using a 200% declining balance method, with a useful life of 25 ;years] $2,434.36 Water and Sewage 96.00 Electric 360.00 Insurance ltJO.OO Maintenance 249.72 Guards, Roads, etc. H~O.OO Total $3,500.b8 Total deductible [90% of $3,500.~] $3,150.07 Total Deductible [not including furniture depreciation] $5,272~07 E8t~mated cost of furniture is $1,500 x 90% business use leaves '$1,350 to be depreciated using the straightline method over a 5 year useful life Total Annual Deductions 270.00 $5,542.07 • If these expenses are allowed, the total tax savings to the Brackets, assuming they are in a 27% tax bracket would be $1,496.36 [$5,542.07 x 27%], assuming further that there are no rentals during the first year. This savings results from a reduction in their yearly taxable income of $5,542.07. One must realize however that this sizeable savings, entiCing as it may appear, would of necessity decline depending upon the amount of rental income derived from the property. These figures are based upon a yearly 16 income of zero. As has been demonstrated in section I of this paper, a continual history of no rental income could very easily be a tip"off to the I.R.S. that there is no profit motive. This is definitely a factor that must be taken into· consideration. Whether all these expenses are deductible is the next question to be answered. Starting first with interest, under Code sec. 163, "a deduction is permitted any taxpayer (in or out of business) for all interest paid or accrued within the taxable year on indebtedness." Secondly, a taxpayer may deduct taxes from his adjusted gross income under sec. 164, ·Reg. 1.164-1. It should be here noted that upon a sale of real estate, the real estate tax deduction must be apportioned between the seller and the buyer according to the number of days in the real property tax year that each holds the property. Prbration is required whether qr not the seller and purchaser actually apportion the tax, and whether they are on the cash accrual basis. Cose sec. 164(d), Reg. 1.164-6. The electricity, insurance, maintenance, guards, roads, etc. should all qualify as reasonable expen~es under sec. 212(1) and (2), for the production or collection of income; or for the management, conservation, or maintenance of ·pr.operty held for the production of income. Likewise, the expenses for water and sewage would qualify under the same section. There is also case authority for the deduction of sewage expense in Thornbrough v. Comm., 11 TCM 227, citing the provision cited above and Reg. 1.212-1. As to the Closing costs, again, most of these expenses should come under sec. 212 [or 162, if this is to be a business] -- including the appraisal fee, the credit report, the legal fees , the recording 17 fee, and the survey fee. Case authority can be found for the de- duction of appraisal fees and legal fees, but none of the cases found would directly apply to this type situation. But, at least one case bas held that the amount paid for a title insurance policy was in the nature of a capital expenditure and was not deductible. "Since the benefits of the insurance extended for an indefinite period, there was no basis upon which amortization could be computed." v. , Comm., 35 TC 454. ture under sec. 263. B.H. Farwell This was considered to be a capital expendiIn light of this, a purchaser may want to include all these "closing costs" in 'his basis in tbe property as in many cases there has been considerable doubt as to whetber they sbould be treated as expenses or capital expenditures. At any rate, the insurance and taxes expenses can be deducted monthly as pointed out above under sections 212 and' 164. The final deduction to be looked at is that of depreciation under sec. 167. Where the property claimed to be depreciable is property used in the trade or business of the taxpayer, or property beld by the taxpayer for the production of income, depreciation allowance is permitted. Schubert v. Comm., 2e6 F2d 573 (CA 4th, 1961), and Reg. 1.167(a)-1(a) (as to property held for the production 'Of income). Where only a part of the property is used for bUsiness purposes or if the entire property is used only partially for business purposes, an apportionment will be made so that only the proportion used for business purposes will be depreciable. Goddard, TC Memo 1962-e3. Charles R. Of course the same is true where the pro- perty is used part of the time for business purposes and part for personal uses. It should be remembered that the taxpayer has the ltl burden to show · the extent of business use which is to serve as the basis for the depreciation deduction. Jay N. Darling, 4 BTA 499, and International Trading Co. v. Conun., 275 F2d 578 (CA 7th, 1960). Where property is held for the production of income, Code sec. 167 (a)( 2) does not require the use of such income -produc,l ng property to 'justify the depreciation deduction. "It would thus seem to follOW that depreciation will be allowable where actual use is not present, if, however, the property is devoted to the production of income." Edward A. Sieg, TC Memo 1961-tltl.Slmllarly, it has been held that depreciation is allowable whe're property, held for production, of income does not in fact produce any income during the taxable year. E.R .. Fenimore Johnson, 19 TC 93 (1952). But, the reader should not be too quick to rely on this last opinion in light of tbe decisions cited above as regards the necessary "pro:(;it motive." 'For the purpose of determining the depreciation deduction, an apportionment of basis must be made between the land and the improvements. Only the portion assigned to the improvements will be re- coverable out of the annual depreciation allowance. Reg. 1.167 (a)-5. , Buildings and other structures are depreciable. Reg. 1.167 As to the method of depreciation, the , purchaser will want to use the declining balance or more likely, the double-declining balance method, under which the unrecovered cost or other basis is depreciated at a uniform rate per annum, the rate not to exceed "twice the appropriate straight line rate computed without adjustment for salvage, but the asset may not be depreciated below its 9 scrap value." Reg. 1.167(b)-2. Regarding the depreciation of sec. 1250 real property, Reg. 1.167 19 (j)-l(a)(l) provides that the double-declining balance and the sum of the years digits methods may be used 'as to residential rental property [new]. As to used residential rental property, the straight- line method under sec. l67-j-4, is used usually, but under sec. l67-j-5, if the property has a useful life of 20 years or more, the 125% declining balance method may be used. To be classified as residential rental property 80% or more of the gross rental income from the building must be from rental income from the, dwelling units. Reg. 1.167(j)(3)(b). [If used residential rental property has less than a 20 year useful life at acquisition, then the straight-line method must be used.] One thing further is that the gross rental income for the 80% test includes the gross amounts received from the use of or the right to use real property. Reg. 1.167(j)-3(b)(2). While on' the subject of depreciation. it would be appropriate to give some thought to the useful life which can be used for this particular type of property. Under the Regs. 1.167(a)-1(b), the rate of depreciation, regardless of the method used to compute the depreciation allowance, depends upon the estimated useful life of the property. Estimated useful life "is not necessarily the useful life inherent in the asset but is the period over which the asset may reasonably be expected to be useful to the taxpayer in his trade or business or in the production of income." The factors to be considered are: (1) wear, tear, decay or decline from natural causes; (2) normal progress of the art, economic changes, current deve~opments in the industry and the taxpayer's trade or business; (3) effect of the climate and other local conditions peculiar to the taxpayer's trade or business; and (4) taxpayer's policy as to repairs, 20 renewals, and replacements. As to the depreciation of buildings, the Commissioner appears to be using the Revenue Procedure 62-21 guideline life [of 40 years] as a ~ 2! thumb for determining the useful lives regardless of whether the taxpayer elects the guidelines. Stevens Realty Co., 26 TCM 528, and C.M. Peters, 2tl TCM 294, where the Commissioner's determination was upheld. But the taxpayers' determinations were up- held in Atlas Storage, 306 F2d 571, and J.M. Richardson, 71-2 USTC Para. 9562. Several cases can be found supporting a useful life of 25 years, but most of them seem to .deal with the acquisition of used commercial property. "In order to eliminate controversy as to the useful life of assets and related depreciation rates, Sec. 167(dO provides that the taxpayer may, for taxable years ending after ,.December 31, 1953, enter into an agreement with the local office of the district director of internal revenue with respect to method, estimated useful life, depreciation rate, and salvage value. Pertinent elements include the • character and location of the property, the original cost or other tax basis, the date of acquisition, and the undepreciated cost as at the beginning of the first taxable year for which the agreement is to be effective. As is true of all depreciation adjustments and arrangements, the agreement is restricted to the prospective treatment of the undepreciated cost as at the beginning of the year. The bur- den of justifying the change is on the party desiring modification of 10 t he agreement should such a change be desired." The final point to be examined in this section is the authority for the proposition that the Brackets will ' be able to take deductions 21 equivalent · to 90% of their expenses and depreciation. A leading case in this area is that of Edward A.Siee, et al., v. Corom., 20 TCM 395 (1961). Here the petitioners were allowed to deduct expenditures in- curred in renting inherited real property even though the will provided that the net rentals should be paid to petitioner's aunt for life if she needed it. · of losses.] [The case dealt primarily with the deduction The property consisted of a two-story building with apartments on the first and se cond floors and in the basement. Petitioner occupied the first floor apartment. The Court stated that · "the fact that one of the apartments may not actually have been rented for the entire year would make no difference if the expenditures were incurred in the management, conservation, or maintenance of the property held for the production of income." Here the petitioners were entitled to expenditures. ded~ct Reg. 1.212-1(b). two-thirds of their Again, potential investors should not be too quick to jump upon this · decision in light of the Carkhuff Case. Remember that here two-thirds of the building was rented out • For those skeptics who st~ll • believe they will have to be en- gaged in the· business of renting 1n order to qualify for the abovemention deductions when they are already engaged in a profession, the following decision should be noted. In Fackler v. Corom., 133 F2d 509, (1943), the petitioner, a lawyer, had acquired a leasehold with the primary intention of operating the building upon it for profit. He was not holding the property merely as an investment, but solely for the purpose of collecting rents without rendering personal service to the tennants. The Court said, "The fact may not be . disputed that a per- son may engage in both a profession and a business." (p. 511) Here, 22 he was actively involved in the management of the property, etc., coming within the definition of "business," and the Court found depreciation and expenses to be deductible. [These expenses could similarly be deducted even if the petitioner had not been engaged in a "business."] In another case it was held that a taxpayer operating a business as an individual may deduct as business expenses, items including interest, state taxes, insurance and repairs paid by check on his personal bank account in making his Income Tax returns. Appeal of George Leavenworth, 1 BTA 754, (1925). 23 III. Sections I and II of this paper have dealt with the deductibility of expenses and depreciation associated with the purchase of new residential rental property in the form of a townhouse -- the amounts deductible and the authority for their deduction. The third and last section will deal with the various possible methods of ownership of this townhouse in which the individusi taxpayer would still be able to off-set the expenses and depreciation against his other income. The methods looked at will be the sole proprietorship, the tenancy in common, and the partnership. HopefUllY this will give the reader some idea as to the best method for his own particular purposes. A. SOLE PROPRIErORSHIP In general, there is no tax differentiation between an inaividusl and a sole proprietor • . For tax purposes they are treated as one in the same. ·"By engaging in a trade.or business, an individual does . become entitled to the whole gamut of bUsiness deductions for ordinary and necessary business expenses -- labor, supplies, advertising, business insurance premiums, repairs, and the like ·. deductible under Code sec. 162] [These would be· DepreCiation of property used in a trade or business and of property held for the production of income, losses in a trade or business, including net operating loss, and the special ordinary loss for bad debts also become pertinent. 11 of Code secs. 167, 165, 172, and 166 respectively]" [By reason If, then, the proprietorship is treated the same as individuals the taxpayer may question, "Why bother with the organization of this proprietorship?" This question could be answered with another question, "It' .a n individual operates the rental of his townhouse as a proprietorship, would it be possible to paY .rent himself when he used it [at a reduced rate, of course], and thus allege the property was used for rental purposes 100% of the time thereby entitling him to a deduction of 100% of his expenses and depreciation?" Although this would appear to be a fairly simple proposition, it has apparently not been frequently used, for there is a noticeable lack of authority on the subject. Particularly in light of the strong stance the Court appears to be taking on these real estate rental transactions, as is evidenced by the Carkhuff Case, this writer feels that such an attempt would be futile. As was pointed out above, the proprietor is treated esseqtially as an individual for tax purposes. Hence, in this case, he would be renting from himself, at a reduced rate, in an obvious attempt to reduce his gross rentals -- thereby increasing his amount of tax loss. If • nothing else, this would appear to indicate a lack of "profit motive." As has been pOinted out in other types of cases, notably the case of Higgins v. Smith, 308 U.S. 473, 60 S.Ct. 355 (1940), a case dealing with the sale of securities by an individual to his own controlled corporation, "the government may not be required to acquie sce in a taxpayer's election of that form 'of doing business which is most advantageous to him, but the government may look at actualities and upon determination that the form employed for doing business or carrying out a challenged tax event is unreal or a sham, may sustain or disregard the effect of the fiction as best 25 serves the purposes of the tax statute." (p. 358) The Court felt, in this case, that "to hold otherwise would permit the schemes 'of the taxpayers to supercede legislation in the dete'r mination of the time and manner of taxation." (p. 358) In other words, this would be another instance of the Courts "piercing the veil" of the entity to determine the true transaction. The investor may argue that in the case of a retail merchant, that merchant is able to buy merchandise from himself at "wholesale," and yet is still allowed to deduct all his expenses . This may be true, but again, in the light of the Court's strong position, this situation would probably not apply in the case of a real estate owner renting from himself, in effect at "wholesale." A Court could quite easily distinguish the two cases on the basis of t~ "de minimus" dootrine • • As to the merchant, his purchase would be very Small in light of his total sales volume, but in the case of the real estate renter, it is quite possible that the only rent he ~ould receive in a given year would be this "wholesale" r ent . The investor should be satisfied with his possible 90%, again in light of the Carkhuff Case where seemingly the owner was entitled to 67%, but was denied a 50% deduction! One poss~ble advantage of the proprietorship method might be that it would make the taxpayer's burden of showing "profit motive" slightly easier, if he could show that he was engaged in a bona fide business. B. TENANCY IN COMMON In looking at a tenancy in common, one can discover several distinguishing features between this arrangement and the partnership: 26 one co-tenant cannot bind the others and his liability is not unlimited; his income and loss may be reported in accordance with his own accounting method separately from the methods followed by . the other co-tenants; and he has a right to partition the property. 12 "The regulations at 1. 761-1(a)(1) state that the co-ownership of property, which is maintained, kept in repair and rented or leased (whether or not through an agent) is a cotenancy and not a partnership. ,,13 When thinking about co-tenancies, it must be kept in mind that state law de finitions are not controlling in the determination of what organizations are partnerships for Federal Tax purposes. Such was the holding of Morrissey v. Comm., 296 U.S. 344, Rev. Rul. 58-243, 1958-1 Cum. Bul. 255. It would appear that whether a relationship is a partnership or merely a joint ownership or expense 14 sharing opera.tion, seems to depend on the . kind of activity present. Determining what kind of activity is required in order for the relationship to be a partnership may be somewhat unclear, but the task may be made easier by the decision of L. L. Powell, 26 TCM 161, • where the Tax Court held that there was no partnership where the co-owners of rental real estate confined their activity to rent collection and making needed repairs and insurance payment. But, as pointed out in the Regs., where the co-owners provide services to their tenants, either directly or through an agent, there is a partnership. Reg. 1.761-l(a)(1), Rev. Rul. 54-369, 1954-2 CB 364. As one writer has pointed out, the decisions recognizing cotenancies have been limited to situations where only real estate was involved, but exploitation of this property or the carrying on of a trade or business by such co-tenants will probably establish 27 a partnership relation. The writer points out several precautions which may be taken to avoid this partnership treatment: confine the purpose of the organization within narrow limits; avoid extensive exploitation of property or operation; each party should insure his respective interest; and each party should have a voice in the 15 management. "Thus, despite the statements of the courts that a cotenancy can avoid partnership status, there is a very substantial danger that the Commissioner will treat it as such. Accordingly, its use will likely be restricted to the limited real estate situations approved by the courts. Its extension beyond these rather 16 narrow limits is perilous." Just how limited these real estate situations must be can be demonstrated by the decision in Demirjian v. Comm., 54 TC 1691 (1970), in which the petitioners .were found to be a partnership as they were providing "services" to the occupants of the apartments. Light, water, and heat was provided! The Court stated, "we are, of course, fully aware of the sentence in the Regs. to the effect that 'mere coownership of property which is main• tained, kept in repair, and rented or leased does not constitute a partnership.' But a critical element in applying this provision is the presence or absence of an 'intention' to carryon a business venture a.s a partnership, with the consequence, for example, that coowners of inherited properties who have not indicated an intention to operate such properties in partnership have generally not been recognized as partners." But, here, the petitioners were "partners." This decision may provide additional authority for a proposition to be posed later in this paper that a partnership can be a "taxpayer." 28 The Court said, "while we agree that a partnership is not a 'taxpayer' under the Code, the legislative history of sec. 703(b) in'" d1cates that the partnership is nonetheless the only entity to make elections affecting income derived from a partnership. According to the House Ways and Means COmmittee, this rule recognizes the 17 partnership as an entity for purposes of income reporting." The . Court here apparently acquiesced in this view as it held the individual petitioners were unable to make the 1033(a) replacement election other than as a partnership. In another case where the group was held to be a partnership, Rothenberg v. Corom., 48 TC 369 (1967), deductions were claimed for cleaning expenses, depreCiation, insurance, Janitor and hauling costs, legal and accounting fees, repairs, supplies, taxes and licenses, telephone, utilities, carpentry, elevator maintenance, • stationary and postage, etc. The Court stated, "the burden of proof was upon the petitioners to show that they and the other individuals did not own and operate the property as members of a partnership." , (p. 373) "The amount and types of expenses claimed by the partnership in its return indicate that the operation constituted the active conduct of a rental business, as distinguished from the mere holding of property for investment." (p. 373) Thus, it was a partnership. For those readers interested in pursueing this aspect, see Comment, "The Single Rental as a 'Trade or Business' Under the Internal Rev. Code," 23 U. Calif. L.R. 111 (1955). The point to be made by the previous discussion is that although two or more persons may wish to engage in a particular venture as ten ants in common, they may be treated as a partnership by the Couz:ts. 29 If so treated, then much of the discussion in the following section will be pertinent to them as well • . C. PARTNERSHIPS This final section will deal with some of the ramifications of purchasing and operating residential rental property in partnership form. "It is because of the schizophrenic nature of a partnership that there are complexities in partnership taxation law not found elsewhere in the revenue laws. A constant awareness that a part- nership, for tax purposes, is sometimes an entity and sometimes an association of individuals [aggregate] is required for an understanding of the operation of present subchapter K and the problems 18 ariSing from this dual treatment." One must also be prepared to encounter the ' operation of both theories \n a single statute. By way of introduction, it should be noted that the entity theory treats the partnership itself as having an existence apart from the individual partners and as such it is capable of engaging • in bUsiness transactions in its own right, apart from the partners themselves. The aggregate or the conduit concept, as it is sometimes called, views a partnership as an association of individuals. Such concept. does not recognize the business organization as having any existence apart from the individual partners. Relative to the purposes of this paper, it becomes of primary ·importance to determine which of these theories will apply should our hypothetical transaction be entered into by persons comprising a partnership. This importance will be adequately illustrated in the application of Code sec. 167(j) to the partnership, not in the case of 30 the original partners, but rather in the event of one partner selling his interest. The remaining discussion will be devoted to a determ~ ination of whether a person buying the interest of one of the original partners will be able to take depreciation deductions based upon "new" or "used" residential rental property. In other words, will this new partner be able to depreciate his acquisition on the sec. 167(j)(2) double-declining balance basis, or will he be limited to the sec. 167(j)(5) 125% declining balance method? With these questions in mind it would be appropriate to look at these two code sections in an effort to find an appropriate sollution: Section 167(j)(2) provides: (A) In General. -- Paragraph (1) of this subsection shall not apply, and subsection (b) [allowing double-declining balance] shall apply in any taxable year, to a building or structure -(i) which is residential rental property ••• , and (ii) the original use of which commences with the taxpayer. • •• Section 167(j)(5) provides: Used Residential Rental Property. -- In the case of sect~n 1250 property which is residential rental property ... , having a useful life of 20 years or more, the original use of which does not commence with the taxpayer, the allowance for depreciation under this section shall be limited to an amount computed under -(A) the straight line method, (B) the declining balance method, using a rate not exceeding 125 percent of the rate which would have been used had the annual allowance been computed under the method described in subparagraph (A), or ••• Looking at the sections cited it becomes apparent that it must be possible to classify a partnership as a "taxpayer," in order to qualify for the double-declining balance method. Basic also to the approach will be a determination as to whether the entity or aggregate 31 theory of partnerships will apply in this particular question. Given the present state of the law on the subject, such a task seems almost impossible. An attempt bas been made to separate these two problems, but there will no doubt be times when it will be difficult to disting. uish between the two. Beginning first with the task of classifying a partnership as a "taxpayer," one is immediately met with the decision in Benjamin v. Hoey, 47 F.Supp. 158 (1942). On page 159 of the opinion, the Court said, "It seems to me there can be no question that the partnership is not the taxpayer. · The law merely requires it to file a return and the amounts of net income allocated to the respective partners in that return, assuming them to be properly computed, are to be and are included in too indiVidual returns of the several partners." But, notwithstanding this decision, a par\nership bas been treated as the "taxpayer" for many purposes as will be demonstrated in the following discussion. In order for the partnership to have "capital gains and losses" • under section 702(a), it must be considered a taxpayer. Unless the partnership is a taxpayer, it could not own capital assets, since this is a tax concept which is specifically defined in section 1221 as 19 " 'capital asset' means property held by 'too taxpayer' " ••• Section 770l(a)(14) defines a "taxpayer" as being "any person subject to any internal revenue tax." As Willis points out in his treatise on Partnership Taxation, section 701 states expressly tbat a partnership "as such shall not be subject to the income tax." "However, the partnership is subject to other internal revenue taxes including, for example, the interest. equalization tax at section 4911 and 32 employment taxes at section 3201. The Regulations properly specify . that the partnership shall make the various elections, referring 20 specifically to some of them." Thus, for purposes of 770l the partnership is a "taxpayer." Also, refer back to the language of the Demirjian Court on page 28. Before jumping into the "entity-aggregate" controversy, it would first be appropriate to define just what a partnership is [or is not]. "The concept of a partnership for federal income tax purposes is more inclusive than either the common law or Uniform Partnership Act definitions. The determination of whether a joint activity is a partner- ship for income tax purposes is made under a uniform national rule, 21 undisturbed by variations in state partnership laws." This "national rUle" may be found in Code section 761(a): "(a) Partnership. -- For purposes of this subtitle, the term "partnership" includes a syndicate, group, pool, joint venture, or other unincorporated organization through or by means of which any business, financial operation, or venture is carried on, and which is not, within the meaning of this title [subtitle], a corporation or a trust or estate. ... II • [The Regulations, sections 1.761-1(a)(1) and 301.7701-3(a) can be looked to for further information] Notwithstanding this definition, there has apparently never been a clear definition of a partnership for Federal Income Tax purposes. According to one writer, "The basic tax definition to be extracted from those regulations might be that a 'partnership' is any organization [unincorporated], consisting of two or more members, used to carryon any business, financial operation, or venture for joint profit, and which does not .c onstitute a corporation, trust, or estate within the meaning 33 22 of the Code ." Working with this basic de finition, we can now attempt to determine which approach, "ent ity" or "aggregate" applies (or should apply) to our problem. According to Willis, "Subchapter K of the 1954 Code side steps the aggregat e~ent ity . adopts neither theory excl usively . confli ct. It Instead it adopts the criterion of the desirable re sult and applies whichever theory will produce 23 that result." An aggregate theory is applied as to whom the income tax will be imposed upon, and as to who will be allowed the various deductions, but generally the rules under subchapter K 24 apply the entity theory. "For most tax purposes, the partnership must be viewed as an entit y separate and distinct from its members. Income earned or loss susta i ned from the business operated by the partnership is income or loss of the entity . Although the partnership entity is not subject to income ta~ ( sec . 701), it is treate d as if it were the t axpaye r for a number of important purposes. For exampl e, the nature of an item of income i s determined from the facts and circumstances at the partnership leve l. The entity is required to file a return (sec. 6031) which computes partnership,taxable income, reflecting important elections, etc. and which allocates the partnership income or loss to the partners." 25 The partnership is treated as an entity for the purpose of computing 'the profits of the partner ship,' and all items of income and deduction are accounted for in the partnership as if it were a taxpayer, so that the individual partne rs need report only their proportionate share of this net amount rather than a share of each individual item. Section 703(a) provides the partnership taxable income shall be computed in. the same manner as for an individual, except that (1) the items described in sec. 702(a) shall be separately stated, , and (2) the partnership shall not be allowed certain deductions to which an individual would be entitled [i.e., the standard deduction under sec. ~4~, the personal exemption under sec. ~5~, etc., and other itemized deductions for individuals under sections 212 through 217.]. These items would be deductible by the ' partners on their individual returns, although possibly paid for by the partnership. "Each partner, in determining his individual income tax, shall take into account his 'distributive share' of each such partnership item. Thus, these items determined at the partnership level will ca:rry ,through to the partners." I.R.C. of 1954, sec. 702; Reg. 1.702-1, T.n. 6175, 1956 Cum Bul. 214-17. The "entity" concept can also be found in section 703(b), which provides that elections [i.e., elections concerning methods of accounting, computation of depreciation, ~tc.] affecting the com- putation of partnership taxable income a:re to be made by the partnership. "Although in many cases a particular partnership election may result in favorable tax consequences for some but not all of , the partners, the treatment applicable to the partnership is binding 26 upon all partners." Reg. 1.703-1(b)(1) (1956) For purposes of section 705, having to do with determination of the partners' basis in partnership property, the partnership is an "entity" apart from the partners. Thus far it has been seen that the partnership is at least an "income reporting" if not a "taxpaying" entity. Confusion has also arisen at to which theory should be used concerning the treatment of a transaction between a pa:rtner and the partnership. Apparently the problem was only further confused by 35 case decisions on the subject. Thus, "because of its simplicity of operation, the 1954 Code adopted the 'entity' approach, but in order to prevent manipulations between a partner and a controlled 27 partnership, for tax purposes, certain restrictions were imposed." In this situation a partner is treated as an unrelated party when he engages in transactions with the partnership, other than in his capacity as a member of such partnership. At least one writer has said that " the entity theory applies to the purchase of a partnership interest. Consequently, the buyer 1s not looked upon as purchasing an interest in the partnership's various assets. Rather, he has purchased an interest in the part- nership entity which will be assigned a tax basis equal to its cost. [see Reg. 1.742-1] But the price paid for the partnership interest and its resulting tax basis probably will ,reflect the value of the assets of the partnership -- cash, receivable, inventory, equipment, 28 intangibles, etc." Looking at the Commissioner's position, we find the case of • Alpin W. Cameron v. Comm., 20 BTA 305 (1930). In this situation there were two partners, A [6~] and B [40%]. A third partner, C, was added and no additional funds were paid in, his capital account being created by a transfer of a 25% interest in the partnership out of A's 6(fj, interest. In the language of the court, "there was no sale or transfer by the old partnership to the new partnership of the assets of the old partnership • ••• The old partners had an interest in a partnership and this interest continued without interruption when the new partnership was created -- at least this was true as B was concerned." Although C was given his interst rather than having purchased it, the Court felt it was a part of the partnership "interest" which was given. (p. 308) The petitioners argued that by bringing in a new partner, a new partnership was formed, thus creating a new taxpaying entity. [for the purpose of re-valuing assets for depreciation purposes, i.e., a new basis for future depreciation allowances] disagreed, and held for the Commissioner. (p. 309) is being used here, entity or aggregate? entity, but actually meant aggregate. The Court Which approach The petitioners alleged The Court apparently went along with the entity theory, saying that the old basis would be used! Finally, under the general rule of sec. 708(b)(l), a partnership will "terminate" for tax purposes only if (1) no part of the partnership's bUsiness, financial operation, or venture continues to be carried on by !!!r of the partners in partnership form or (2) there occurs a sale of exchange of 50% or more of the total interest in the partnership capital and profits within any 12 month period. The Regulations elaborate on the 50% rule in 1.708-1 (b)(l)(ii) (1956). There will be termination under the 50% rule only by reason of "sales or exchanges" of partnership interests (as opposed to "an interest in the partnership") [including sales to other partners]. Transfers of interest by gift, bequest, or in- heritance and changes in ownership resulting from liquidation of interests or contributions to the partnership do not constitute sales or exchanges. Termination would not occur unless 50% or more of the total interest in both capital and profits were sold within 37 the 12 month period • . For example, there would be no termination if 70% of the total interest in capital but only 40% of the total interest 29 in profits were sold." By virtue of the 50% rule and Reg . 1.7oB-l(b)(1)(iv) a " con- structive liquidation" t ake s place, wher eby the "distributee s" are deemed to have immediately contributed the properties received to a 30 ~ partnership. Without regard to problems involving the basis in the property re s ulting from thi s transaction, valuable tax benefits have been lost in that (relevant to this paper) the new partnership would not be the "first user" of property previously held by the original partnership. Therefore, the accellerated method of depre- ciation (i.e., double-declining balance) which is available only for new property would be lost, with r espect to such assets, not only to the destr1butee, but to the original partQer who did not sell as well! 31 Reg. 1.167(c)-1(a)( 6 ) (1956) Thus it appears that the I.R.S. is using an "aggregate" theory of partnership, since it speaks of the new partnership as ~ being the "first user" of this property. If, then, this is .the case, a partnership could get around this rule by having the selling partner sell his "interest in the partnership," as opposed to his "interest in the partnership assets" [i.e., the "partnership capital and profits" as provided in sec. 708(B)(1)]. In other words, sell his interest in the entity as opposed to his share of the assets. Granted this is a technical distinction, but there is authority for the proposition that there is a difference between selling a partner's interest in the assets of the partnership, and his "partnership interest." [see the Cameron Case above] Thus, if this is true, then the original partnership which was the "first user" of the property would still be the user of the property and therefore entitle d to the same double-declining balance method of depreciation. That there is support for the entity theory as applicable to at least some aspects of partnership taxation has been demonstrated in the preceeding pages. It would appear that the I.R.S. has confused its position regarding the 'entity' or 'aggregate' approach. As to sec. 708(b)(1) the I.R.S. seems to be following the aggregate approach in that the criteria for the "termination" of the partnership is that there must be a sale of a 50% or more interest in the partnership assets (Le., capital and profits). [Under the "entity" theory the cri- teria for termination would be the sale or exchange of a more partnership "interest."] 50% or Again, unde.r Reg. 1.708(B)(1)(iv), the loR.S. thinks in terms of an "aggregate" test.. Here they assume that by purchasing a percentage of the partnership assets (as opposed to an interest in the partnership), and thence by a process of • constructive contribution, the distributees become ~ partners. Therefore, according to the I.R.S., under the aggregate theory there are new partners and thus a new partnership which under sec. 167 would not qualify as the "first user" of the respective assets. But, a flaw appears in this last analysis. If, as the aggregate theory asserts, a partnership is not an entity in itself, but an aggregate of individual partners, how can the I.R.S. assert that ". the " new partnership" couldt no quali f y as the "f irs t user. Assuming there were originally two partners and one of them sold out, is not the remaining partner still the "first user1" Thus, should 39 not the partnership be allowed the use of the double-declining balance method at least as to his one half of the assets? sistently with the aggregate approach, yes. Con- If a partnership is merely an aggregate of individuals, the n why should not this one individual be entitled to the same deduction he was receiving . before his partner sold out? But, the I.R.S. says no, this is a new partnership and thus not a "first user." Thus, as demonstrated above, the I.R.S. apparently has decided that in this instance the aggregate approach to partnerships should and will apply. The confusion (or inequity) arises in that by maintaining this position they have frustrated, in part at least, the purpose of the section that purpose being the encouragement of construction of new housing. The attractiveness of entering into this field will certainly not be enhanced by the knowledge that the douQle-declining balance method of depreciation will no longer be available should the partnership for some reason be dissolved and restructured. Again, a possible "end-around" ~ be achieved by strict technical compliance with the wording of s ections 708 and l67(j)(2). The important thing .to be discerned from all this is that the I.R.S. has treated t he partnership itself as the owner of the property, the "original user" of the property since they assert that under the aggregate theory the "new" partnership would not be entitl ed to the same depreciation deduction as the "old" partnership. Thus, for this purpose the partnership is considered the "taxpayer." there is compliance with sec. l67(j)(2)(A)(ii): Hence there is property "the original use of which commences with the taxpayer." Therefore 40 if a partnership owns [or is contemplating purchasing] new residential rental property which will be subject to the double-declining halance method, after such purchase has taken place, and depr eciation has begun under this method, the partner wishing to maintain his interest in the property should, if his partner decides to sellout, make sure that his partner sells his "partnership interest" as oppose d to his "interest in the partnership assets. n Similarly, the partner wishing to sellout could sell his interest to the remaining partner and that partner could in turn sell an "interest in the partnership'" to the prospective new partner. Thus, the original user of the property is still the owner and should be able to continue depreciating at the double.-declining balance rate. As a final remark I shOUld point out that I realize the clusions I have drawn are based upon a ver~ con~ fine distinction, but I also realize that many fine distinctions have created new law before, especially where the positions are as confused as they seem to be here under present I.R.S. construction. This is not to say, of course, that .the view I have presented is infallible or that the I.R.S would in any likelihood accept this interpretation. At l east, under this method, partial equity is done in that the original partner is able to continue fulfilling what was an important consideration in his undertaking the venture -- the consideration of rapid depreciation in the early years of his investment. One final point is that this interpretation would probably work best in a three-man partnership situation in light of the 50% rule of sec. 708. 41 Citations 1. John R. Carkhuff v. Comm., 28 TCM 375,378. 2. Id. 3· .!i., p. 380. 4. Reg. 1.212-1(c): ..• "The question whether or not a transaction is carried on primarily for the production of income or for the management, conservation, or maintenance of property held for the production or collection of i ncome, ••• is not to be determined solely from the intention of the taxpayer but rather from all the circumstances of the case." 5. Carkhuff, supra ., p. 1403. 6. Id., p. 1405. 7. Id., p. 1405. 8 . Dohan, Deductibility of Non-Business Legal and other Professional Expenses; Expenses for Creation ,or Protection of Income or Property, Divorce, etc., 17 N.Y.U. Inst. on Fed. Tax. 579, 601. 9. (1967) • 10. P. Anderson and R. Wilson, Tax Planning of Real Estate J. Mauriello, Businessman's Federal Tax Guide (1971), p. 354. 11. Tax Choices in Organizing a Business, CCH Tax Analysis Series (1969), p. 36. 12. J. Pennell and J. O'Byrne, Federal Income Taxation of Partners and Parnerships (1970), p. 26. 14. Partners hi Sales and Li Effects, CCH Tax Analysis Series -- A Look at the Tax 12. 15. J. Pennell and J. O'Byrne, supra note 12, p. 27. 16. .!i" 17. Demirjian v. Comm., 54 T.C. 1691 (1970), p. 1700. at 27· 42 18. Anderson and Coffee, ~P~r~o~p~o~s~e~d~~~~~~~~~~~~ Partnershi Taxation : Analysis of the on Subchapter K, 15 Tax L.R. 2 5, 2 7 at 291. 19 . ~., 20 . A. Willis, Willis on Partnership Taxation (1971), p. 140. 21. Id., at 3. 22. Bibart, Partnership Taxation, 40 Cinn.L.R. 456 (#3. 1971). 23 . Willis , supra at 8. 24. Id. , p . 9. 25. Bibart, supra at 462 . 26. ~., p. 463 . 27. see Sec . 707(b) I.R.C. (1954), and Mertens, Law of Federal Income Taxation, §35.• 55, p . 197-8 . 28 . Partnership Sal es and Liquidations, supra note 14, at 62. 29. Bibart, supra at 501. 30. The writer realizes that technic~lly, the 50% rule of sec. 708(b )(1)(B) will cause difficulties with the theory presented. This was the reason for suggesting that the three - man partnership situation would be the eas i er situation in which this theory could work. Feeling that this particular section goes beyond the scope of this paper, a consideration of the r amifications of t hi s section was not undertaken. The obv ious sollution of the problem a~ it relates to this t heory would be for one partner to own a 51% interest while the other owned a 49% i nterest. This would have t o be worked out among the partners in accordance with their desires as to how long they wish to hold the property purchased. For further examinat ion of the subje ct, refer to . Willis, s upra at 313. 31. This paragraph was taken partially from Bibart, supra at 502.