COMMUNITY DISRUPTION AND HIV/AIDS IN THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA American University

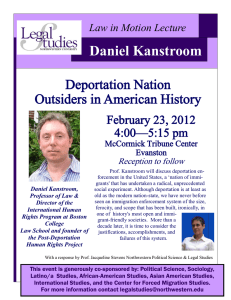

advertisement

COMMUNITY DISRUPTION AND HIV/AIDS IN THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA September 13-14, 2012 American University DEPORTATION Presentations Julia Dickson-­‐Gomez, PhD: Professor, Center for AIDS Intervention Research, Medical College of Wisconsin “Left Behind: The Effects of Immigration on Salvadoran Children, Families and Communities” • Dickson-­‐Gomez's presentation examined global population movement and the implications of immigration and deportation on Salvadoran communities and vulnerability to HIV. Her qualitative research found that deportation and being left behind when family members emigrate causes social disruption that creates cycles of frustration and hopelessness that increase HIV risk, including drug use, lack of family support and parental involvement, gang activity and crime. Victoria D. Ojeda, MPH, PhD: Assistant Professor, Division of Global Public Health, Department of Medicine, University of California at San Diego “Deportation Experiences of Mexican Drug Users: Implications for U.S.-­‐Based HIV and Drug Use Research” • Ojeda explored the implications of deportation for Mexican immigrants and presented findings from research conducted amongst a cohort of injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico. Deportation was found to contribute to feelings of social isolation, particularly women separated from their families, and increased drug use and likelihood of being HIV positive. Luis H. Zayas, PhD: Dean of the School of Social Work and Centennial Professor in Leadership at The University of Texas at Austin “From Case to Cause: Protecting Citizen-­‐ Children through Practice, Research, and Advocacy” • Zayas' presentation addressed the psychosocial impacts of deportation on children, particularly for mixed status families in which children are U.S. citizens but one or both parents are not. He explored implications for mental health outcomes, policy and the immigration system and courts. Key themes: • Deportation disrupts families, which contributes to mental health problems for children and can lead to unhealthy behaviors, like drug use and gang activities, and increase risk factors for HIV. U.S. citizen children whose parents are 1 Community Disruption and HIV/AIDS In the District Of Columbia, Sept 13-14, 2012 American University • • • • • deported face emotional, health and cognitive hardships, which could negatively impact their physical and mental health. Both actual deportation and the threat and fear of deportation have short and long term impacts on health and communities, particularly because of psychological and emotional trauma, stress and anxiety, and economic hardships. Deportation has potentially adverse health impacts on U.S. citizen children, which is relevant for policymakers and public health policy, and places pressure and strain on the foster care and juvenile justice system. Research on the health impacts of deportation and "deportability" can be useful for understanding the health impacts of policies and potential structural interventions to address them. Disruptions associated with both migration and deportation can provoke HIV related risk behaviors in both the U.S. and sending countries, particularly drug use and sex work. Deportees may develop or increase drug use as they lack social support and drug rehabilitation and HIV/AIDS treatment resources in their home country. Immigrants may develop drug addictions in the U.S., which leads to deportation and further behaviors related to risk for HIV/AIDS. Deportation is becoming increasingly important given the criminalization of immigrants, increased rates of deportation due to automatic removal and lack of judicial review and policies such as Secure Communities and state and local anti-­‐ immigrant ordinances. Deportation Working Group Research gaps: • Little understanding of the impact of deportation on communities and families left behind in the U.S. or in sending countries where people return. There is research on criminalization and immigration but not explicitly on deportation. • Limited data and social science research constrains the development of effective policy and other structural interventions to address health. • Lack information on the impact of deportation on U.S. citizen children, including overall quality of life, stress, access and willingness to seek out social services, i.e. HIV testing or drug treatment. Research is just beginning on the impact of being in foster care or adopted after parents are deported. • Lack evidence about supposed self-­‐deportation and health impacts of anti-­‐ immigrant ordinances in states like Arizona and Alabama. Research questions: • What are the health outcomes of illegality or “deportability”? Are there ways to differentiate the adverse effects of deportability from deportation? Also, need to 2 Community Disruption and HIV/AIDS In the District Of Columbia, Sept 13-14, 2012 American University consider that people with documentation can still be deported and not assume a binary between documented and undocumented people. • How does deportability contribute to stress and overall quality of life? What are the implications for accessing social services, particularly HIV testing and accessing treatment and other services for HIV and drug use? • How are U.S. citizen children impacted by deportation? • What are the impacts on sending communities? How are both families and communities impacted in both the U.S. and Latin America? What are the implications for health and community disruption of moving back and forth between U.S. and sending countries? • What are the impacts of deportation on the foster care system, courts, health disparities measured through multiple variables including stress, HIV and mental health, educational outcomes, and costs to social services? Are deported people at risk of homelessness, drug use or alcoholism, and other HIV/AIDS-­‐related risks? • What are the gendered dimensions and implications of deportation? • Need to understand process of deportation and who is being deported and for what reasons. • Are there differences between different Latino immigrant groups and non-­‐Latino immigrant communities? • How are current immigrant laws contributing to self-­‐deportation and what are the impacts on communities and health, particularly risky behavior, sexual partnerships and access to services? • What are the implications of people moving back and forth across the border? Is mobility different for people who have been deported? Potential research projects: • Transnational studies could incorporate systematic, comparative analysis across state borders in the U.S. and national borders in Latin America, particularly Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. In the U.S. focus on several major receiving cities and connections between particularly communities in Latin America and the U.S. • Multi-­‐city and multi-­‐population study that compares different Latina communities and different countries of origin. • Longitudinal study could track people as they move back and forth between the U.S. and their country of origin. Examine issues of mobility between U.S. and Latin America, and notions of self-­‐deportation. People who’ve been deported and are back in sending communities might be more open to participating in research – no longer fear of deportation. • Examine impacts on broader U.S. society as well as individuals and immigrant communities. • Include expertise and perspective from social and behavioral sciences, law, social work, advocacy and policy organizations. 3 Community Disruption and HIV/AIDS In the District Of Columbia, Sept 13-14, 2012 American University Sources of data and methodologies: • Need to determine primary units of analysis, dependent variable and outcome(s). Whose story are we attempting to reflect in our research? What is our dependent variable? • Possibly focus on U.S. citizen children and broad health impacts. • Multiple different populations: self deportation, migrant families living in the U.S., families who left behind when a member is deported, young single men who are deportable but do not have family in the U.S., families in sending communities, people who have been deported and integrated or not integrated back into their communities • Unit of analysis: individuals or households? • Large-­‐N vs. small-­‐N surveys: want data that allow for extrapolation to national level. • Sampling strategies – community-­‐based, get contacts through Latin American consulates to conduct survey. • Ethnographic, interview and other qualitative research that captures stories and processes and could help inform questions on a larger survey. • Participatory and community-­‐based research that actively engages communities, particularly necessary for a vulnerable and silenced population. • Disaggregate relevant populations across and within sending/receiving locations. • Social network analysis. • Include expertise and perspective from studies of the law, as well as the obvious social and behavioral sciences. Other potential activities: • Sharing info and contacts about related work underway, perhaps adding components or expanding on currently funded NIH projects -­‐ e.g. Luis Zayas (Dean of the School of Social Work and Centennial Professor in Leadership at The University of Texas at Austin) and Julia Dickson-­‐Gomez (Center for AIDS Intervention Research, Medical College of Wisconsin). • Possible conference on deportation and health focused in part but not exclusively on HIV/AIDS hosted by CAIR. • Link research to community based partners and complete understanding of immigration and deportation laws and interventions to reduce disruptions and negative health outcomes. 4 Community Disruption and HIV/AIDS In the District Of Columbia, Sept 13-14, 2012 American University