THE ETHICAL CONFLICT OF CLIENT CONFIDENTIALITY AND CANDOR Independent Research

THE ETHICAL CONFLICT

OF

CLIENT CONFIDENTIALITY AND CANDOR

Independent Research

Presented To

Professor Cummins by Thomas A. Beall

Spring 1981

26

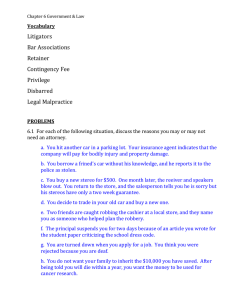

Dean L. Ray Patterson has noted that the three principles of conduct for attorneys are "loyalty to the client, candor to the tribunal, and fairness to the opponent."^" This paper will examine the first principle, loyalty to the client, and its inherent conflict with the second principle of candor to the tribunal. Specifically, the paper will concentrate on the element of client confidentiality (and the preservation of these confidences) in an ethical context as opposed to a duty to disclose these same confidences in order to carry out a duty of candor to the tribunal. The ethical conflict ultimately is "based upon resolution of the question: Who does the attorney serve "before any competing or conflicting interest? If the lawyer's primary duty is to the client, then the lawyer should not disclose information to the court which is damaging to the client; conversely if the primary duty of the lawyer is to discover the truth so as to achieve justice, perhaps disclosures which are damaging to the client should "be made. As might "be expected, there is no clear delineation of duty for the legal profession.

One of the first government scandals from the past decade, which received nationwide attention, involved the desire for confidentiality from a "client" and society's demand for the truth: Watergate. Although the Watergate scandal was not viewed as a legal ethics problem; John Dean, as counsel to the

President was aware of confidences and secrets which would be

27

E e a l l -

40

-

41 detrimental to his client. The preservation of those secrets led to a "cover-up" of the truth. Disclosure of these improprieties on the other hand would have served the intent of justice and saved the nation much anxiety. It is acknowledged that during the "cover-up", Mr. Dean was not "before any specific court, but the perception by the public was one of deception. In light of the above scandal, attorneys need precise and clearly delineated ethical standards to govern their course of action.

The dilemma of the two competing duties has frustrated the courts. In 1976 the Supreme Court of Oregon considered a case where an attorney was disciplined for allegedly misleading a court. The client in that divorce case was asked by opposing counsel where his mother was at that time. The client replied

"Salem", but failed to add she was buried in the cemetery as opposed to still being alive? his attorney felt the court did not understand this fact and wanted the client to volunteer the information. The client refused, fearing questions on his mother's death would lead to an adverse property division by the court.

On appeal of the disciplinary hearing (concerning the lawyer's failure to disclose the truth), the court noted there was

"...substantial disagreement in the Bar over which rule takes precedence in this kind of situation—the duty to disclose or the duty to protect the client's confidences and secrets..."

Feeling it would be unfair to discipline that particular attorney, the court dismissed the complaint; but, they noted that thereafter attorneys in similar circumstances would be obliged to disclose or withdraw.

28

Beall -

2

0-

Earlier it was stated that this paper will analyze the concept of client confidentiality in an ethical context. This review will trace the development of client confidentiality from the American Bar Association (hereinafter "ABA") Canons of

Professional Ethics (hereinafter "Canons") through the current

Code of Professional Responsibility (hereinafter "CPR"){ this brief review will also consider ABA opinions, cases, and commentary which are concerned with the topic of client confidentiality. The analysis will then shift to the ABA Kutak Committee's proposed Model Rules of Professional Conduct^ (hereinafter

"MRPC") and its treatment of confidentiality. Responses and reactions to the MRPC will be considered, as well as alternative proposals of other organizations. Two alternate proposals which will be considered are the Roscoe Pound-American Trial Lawyers

Foundation discussion draft entitled "The American Lawyer's

Code of Conduct"

6

(hereinafter "ATLA") and the National Organization of Bar Counsel's Report on the MRPC,

7

(hereinafter "NOBC").

In December 1980, just over eleven months after the release of

Q the MRPC, the Kutak Committee mailed a clarification letter to those who had expressed interest in the MRPC. The clarification letter will also be discussed.

Formal ethical guidelines were first adopted in 1908 as the Canons of Professional Ethics. Canon 37 (see Appendix A) deals with confidence of a client. It provides in the first sentence that the duty of a lawyer is "...to preserve his client's confidences."^ Although the Canon does not define the extent

Beall -4-3of this general duty, it does provide the lawyer and his employees should not accept employment which "may involve the disclosure or use of these confidences..."

10

(emphasis added.). As exceptions,

Canon 37 permits the lawyer to disclose the truth in order to defend himself from an accusation, or to make disclosures with the knowledge and consent of the client; in any other case, rather than breach the duty of confidentiality the attorney should

11 discontinue employment so as to avoid possible conflicts.

It should be pointed out that Canon 37 does not impose an affirmative duty to disclose any confidence of a client. Further-

12 more, Canon which is concerned with fraud or deception imposed on the court or other parties is phrased in terms of what the lawyer should do instead of an affirmative duty such as would be apparent from use of the word "shall." Thus the permissive disclosure of Canon 37 and the advisory language of

Canon bl fail to overcome the unqualified duty to preserve confidences expressed in the first sentence of Canon 37.

Shortly after the adoption of the Canons one writer stated that being a lawyer imposed a "positive duty" to maintain confidences of the client, that there was "no right to disclose confidential communications" without the clients consent, and that maintaining this confidence was a matter of "professional honor. The author went on to note that "...it is the lawyer's of the client. These excerpts, plus the discussion of Canon 37 give support for the proposition that originally the balance

30

Beall -4-3between confidentiality and the disclosure of client's secrets accorded more weight to confidentiality. An attorney could make disclosures under certain circumstances, but these disclosures were viewed as exceptions to the general rule prohibiting the disclosure of secrets confided in the attorney by a client.

The policy supporting client confidentiality is most often described as a guarantee for the client so he can give his attorney all the facts the attorney needs. In order for an attorney to fully develop his case, the client must feel free to tell him all relevant facts; even those which are embarrassing or admit guilt or liability. A client fearing his attorney might disclose facts to the court which would be damaging to the client would presumedlynot give the attorney those facts rather than risk an adverse judgment. It is simply human nature not to voluntarily put oneself in peril; accordingly client confidentiality serves as an assurance to the client that prejudicial information given to the attorney will not be disclosed. In one of its formal opinions,^ the ABA noted that client confidentiality was "... essential to the administration of justice..." in order to promote "...perfect freedom of consultation by client with attorney without any apprehension of a compelled disclosure by the attorney to the detriment of the client."^"

6

(emphasis added)

The concept of client confidentiality (an attorney will not disclose damaging information when given to him by the client) appears strong on its face, but it makes some assump-

31

Beall -4-3tions which are not always going to be valid. The primary assumption is that a client who knows his attorney will not disclose his confidences will therefore tell his attorney everything about the dispute. Admittedly many clients will truthfully disclose everything they know to their attorney, but there also will be those who will lie or not disclose vital information to their lawyer despite the lawyer's assertions of confidentiality.

That being the case, should "client confidentiality" be modified?

One of the earliest ethics opinions interpreted the meaning of client confidentiality. ABA Commision on Professional Ethics,

Opinion No. 23 • The Committee determined in Formal Opinion 23 that it was "...in the public interest that even the worst criminal should have counsel, and counsel cannot properly perform their duties without knowing the truth." They concluded an attorney should not disclose the hiding place of his client who had jumped bail. The two sentence decision also noted that required disclosure by an attorney would "...prevent such frank disclosure as might be necessary to a proper protection of the client's interest." Just six years later another ethics committee reached the opposite result on similar facts.

In 193^, the ABA Commission on Professional Ethics issued

17 two opinions which limited the duty of client confidentiality.

The facts in Formal Opinion 155 dealt with a defendant who had jumped bail and left the state. The attorney knew the location of the defendant, and was required to disclose the address. The

32

Beall -4-3-

Ethics Committee acknowledged the duty to preserve client confidences, "but they stated that when the confidential communication was in regards to "the future commission of an unlawful act

1 R or to a continuing wrong, the communication was not privileged."

The rationale for this result was "reasons founded on public

19 policy."

7

Those reasons were not given. The second opinion, issued the same day, provided that knowledge of a parole violation was a continuing wrongdoing, which the attorney must dis-

"that the relation of attorney and client... be used to conceal

21 wrongdoing on the part of the client." The Committee concluded that the attorney was an officer of the court, and "must obey

22 his own conscience and not that of his client."

Then in 1953 the Committee issued Formal Opinion 287.

This time the committee returns to the views of confidentiality expressed earlier in Formal Opinion 23. The facts in Opinion

287 concerned a client who—without his lawyer's knowledge— perjured himself at his divorce hearing. Later the client's exwife attempts to blackmail him regarding the perjury. The client returned to his lawyer, admitted his perjury, and sought legal advise. The ethical question concerned whether the attorney should reveal the perjury to the court. The Committee determined he should not disclose those facts. The significance of this

Opinion is evidenced by the Committee's statement that they did not "consider • the duty of candor and fairness to the court... sufficient to override the purpose, policy and express obli-

33

Beall -4-3gation under Canon 37."

The Committee urged the lawyer to advise his client of the need for disclosure; if the client refused to disclose the information then the attorney should "...have nothing further to do with him; but despite Canons 29 and /""dealing with the disclosure by the attorney of perjury and of fraud or deception occurring in court _J7 should not disclose the facts to the court or to the authorities."

2

^

The Committee restated its commitment to confidentiality in a second fact setting in Opinion 287. In the second case the clerk of the court stated the defendant had no prior record; the attorney knew this to be untrue, but was reluctant to volunteer this information which was undeniably damaging to his client. The Committee recognized the attorney's obligation of loyalty as an officer of the court, but concluded that if the lawyer was not furthering the misunderstanding through his own

26 statements, then he need not speak out.

Although the Formal Opinions and Canons were not always consistent, there is support for the claim that generally the duty to maintain preservation of the confidences and secrets of clients were to be accorded more weight than the duty to disclose the

27 inadmissible as a breach of confidential communications.

The court noted that a privileged communication, unless waived, no

"...remains privileged forever..." It should be pointed out that the disclosure involved was not of fraud or deception im-

34

Beall -4-3posed upon the court, but of facts detrimental to the clients interest. Nonetheless, confidentiality prevailed over the truth.

The House of Delegates to the American Bar Association adopted a Code of Professional Responsibility in

1969 J

it became effective January 1, 1970. The CPR was designed to replace the Canons and provide new guides to attorneys in the area of ethical conduct. It is comprised of Canons which are "statements of axiomatic norms" that embody the concepts, delineated in

29

Disciplinary Rules and Ethical Considerations.

7

The Disciplinary Rules are mandatory in character; whereas the Ethical toward which lawyers should strive.

Canon Four of the CPR (see Appendix B) governs client confidentiality. It is a retreat from the position taken in

Formal Opinion 287; although client confidentiality is still recognized as a very important aspect of the practice of law, it is no longer "the most equal" of competing ethical requirements.

As already noted, Canon 37 of the previous standards provided an unqualified duty to preserve the confidences of a client; Canon k of the CPR states the lawyer "should preserve the confidences and secrets of a client."^

1

(emphasis added) The distinction is subtle, and in large part results from a desire to make

Canon 37 more precise. The CPR in DR b-101 defines "confidence" and " s e c r e t " , p r o v i d e s what a lawyer "may" r e v e a l , w h a t the lawyer "shall not" disclose,^ and directs the lawyer to prevent

35

others having access to such material from making disclosures.

J

It was suggested earlier that the CPR retreated from the duty of confidentiality expressed in Canon 37. That should not suggest the ABA had reversed its position. Disciplinary Rule

4-101 still provides a "lawyer shall not knowingly...reveal a confidence or secret of his client."-^ The subtle retreat is evidenced by beginning the r u l e ^ with the word "except"as compared to the unqualified expression in Canon 37. Secondly, the prohibition of disclosure has lost its prominence as the first sentence in the general rule; following a section on definitions. It is interesting to note that the ABA chose to place the definitions of "confidence" and "secret", in DR ^-101 as opposed to being in the definition section following Canon 9.

The logical conclusion is that the two terms are too important to be placed in a "definitions" section; yet, the meaning of sections permitting or prohibiting disclosure has not changed.

Regardless of the AEA's intent, the first impression impact of an affirmative duty to preserve client confidentiality does not exist in Canon ^ of the CPR; the duty is qualified by exceptions in the second section of the rule. The change in location and form create the appearance of a change in priorities.

During the 1970's, the unresolved conflict of duties to preserve client confidence and secrets, and duties to promote the integrity of the legal profession through prevention of judicial deception continued in spite of the CPR. One writer considers a hypothetical posed by another.-^ The innocent de-

36

JJean - J. J.fendarit in a murder case is convicted and sentenced to be executed; the lawyer knows that one of his clients actually committed the crime, not the now convicted defendant. What course of action should be pursued? The author suggests an attorney could find support for a "decision to remain silent or a decision to dis-

39 close but regardless of the choice made would not be subjected to disciplinary action because of the absence of a clear choice kn of conduct in the CPR.

Perhaps as a result of the weakness of a code of ethics which generally supports client confidentiality while permitting disclosure (under certain circumstances) at the same time, lawyers have polarized.

Judge Marvin Frankel feels strongly "...that our adversary system rates truth too low among the values that institutions of ki justice are meant to serve." Whether in anger or in frustration, Judge Frankel argues lawyers are rarely engaged in a search for the truth in resolution of their disputes; moreover, he contends the rules of adversary litigation are designed to ko defeat the truth. He is not accusing the legal profession of consciously working to deceive the courts, but in placing primary emphasis on winning for the client. Frankel would argue that lawyers present evidence favorable to their own position, and let the truth contend for itself. Responding to the claim that "...the clash of adversaries is a powerful means for hammering out the truth" Frankel says the legal profession is practicing self deception.^

37

Beall -4-3-

In order to resolve this problem, Judge Frankel proposes that the legal profession should:

(1) Modify (not abandon) the adversary ideal,

(2) Make truth a paramount objective, and

(3) Impose on the contestants a duty to pursue that objective.

These changes would be implemented by a revision of DR 7-102.

Judge Frankel's draft of DR 7-102 would (unless prevented by an applicable privilege) require lawyers to disclose the existence of relevant evidence or witnesses the lawyer did not intend to use, report any perjury or the omission of material facts to the court and to opposing counsel, and to question witnesses with a purpose and design to elicit the truth.

J

In addition to these required disclosures (the language states "a lawyer shall..")

Frankel imposes a presumption of knowledge in the lawyer of the facts or evidence covered by the disclosure rules. Although the author's treatment of client confidentiality is not discussed, it is clear that under his proposal the ends of justice are served by discovery of the truth; confidentiality would have to be subordinate to that end in the event of conflict.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is Dean Monroe Freedman; his position is one of absolute confidentiality. Responding to

Judge Frankel's proposals in a search for the truth, Freedman submits that they are "radically wrong." Freedman concedes the trial is in part a search for the truth, but maintains our adversary process "is one of the most efficient and fair methods designed for determining..." the truth. The adversary system works to discover the truth by presenting

38

Beall -4-3to an impartial judge or jury a confrontation between the proponents of conflicting views, assigning to each the task of marshalling and presenting the evidence in as thorough and persuasive a way as possible. k9

Freedman's adversary system assumes attorneys will diligently investigate the case, discover all relevant information and evidence—favorable or otherwise--and present it to the court.

Unfavorable evidence not presented by one side will be produced by the opponents so that in the final analysis the truth is discovered by the trier of fact.

The shortcoming of Dean Freedman's adversary system is that even the most diligent and eminently qualified attorney could fail to discover material evidence despite a thorough investigation. Such a fate would be compounded by the reluctance of opposing counsel to admit weaknesses in their own case.

Judge Frankel's proposals would avoid this problem through disclosures; but the weakness of such a system is that the less than diligent attorney could potentially be delivered significant information without any investigation on his own. Granted, the truth would be known; but there is an inherent inequity of requiring an attorney to not only develop his own case, but to also produce information for the other side.

Freedman recognizes the intent of a client to commit a crime as an exception to "absolute" confidentiality,^

0

but he notes

" even in that exceptional circumstance, disclosure of the confidence is only permissive, not mandatory."^

1

(emphasis added)

Freedman finds support for his views as confidentiality in the constitutional right to counsel. If the client could not freely

39

Beall discuss the facts of the case with an attorney, out of fear of disclosure, then he would effectively "be denied his right to counsel. Secondly, Freedman feels that the adversary system preserves the dignity of an individual "even though that may occasionally require significant frustration of the search for truth.

nJ

If the "best interests of the client are served, Freedman has no objection to frustration of the truth; pointing out the fact that lawyer in criminal cases advise their clients not to make statements to the police, Freedman states the lawyer may have a professional obligation "to advise the client to withhold the truth..."

53

In an earlier article, Freedman discussed the conflict of client confidentiality and candor to the tribunal in the context of what he felt to be the three most difficult ethical questions:

1) Should an attorney try to discredit an adverse witness when the attorney knows that testimony to be the truth?, 2) Should the attorney put a witness on the stand knowing he will commit perjury?, and 3) Should the attorney give his client advice that would tempt the client to commit perjury? Freedman answers all three questions in the affirmative, relying on policies of maintaining an adversary system, a defendant's presumption of innocence , putting the prosecution to task to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, the right to counsel, and client confidentiality in general.

Of the three, the most controversial (at least for this writer) is Freedman's treatment of the client desiring to commit perjury. Freedman advises the attorney must try to disuade the

Beall -4-3client, and advise him of the opposing counsel or the court discovering the perjury, but if the client chooses to commit perjury the lawyer must put him on the stand. Moreover, the attorney should guide the witness through the perjury with direct examination questions, and then argue the perjured testimony to the j u r y . F a i l u r e to do so would be a tip-off to the jury, and therefore be detrimental to the client. Freedman not only argues there is no alternative to this course of action, he feels the Canon 37 exception to the duty of confidentiality

(announced intention of a client to commit a crime) does not apply in these circumstances.-^

Some lawyers felt Freedman's remarks went beyond controversy, they filed complaints with the grievance committee of the

District of Columbia urging Freedman's disbarment or suspension.

The matter was eventually dropped without disciplinary action being taken.

The views expressed by Dean Freedman are at the very least a return to the duty of confidentiality stated in Canon 37? at most they are a leap beyond Canon 37 to an even stricter duty of confidentiality. His arguments have a nostalgic appeal; rather than having an attorney to represent the client in court,

Freedman's adversary system suggests the attorney is a soldier fighting on the field of justice, yielding nothing to the enemy, and giving his all for the best interest of the client. The flaw in Freedman's adversary system, that almost disregards candor to the tribunal, is its dependence on a criminal trial setting. This narrow scope makes for an inflexible code of

41

B e a l l - 4 - 3 conduct, in that there are no provisions for guidance of the lawyer in roles other than criminal defense. Dean Freedman might have intended strict confidentiality to apply to all legal settings, "but if that was his intent he did not pursue it.

Another response to the proposals of Judge Frankel refused to accept his full scheme of disclosure in the search for truth, but it by no means approached the degree of confidentiality required by Dean F r e e d m a n . P r o f e s s o r Uviller felt that history and cultural traditions link attorneys to some degree of confidentiality. These traditions are so strong that the legal profession cannot "tolerate an affirmative duty of been trayal..."^ Uviller's alternative would make presentation

(or toleration) of deceptive testimony unprofessional conduct; under Frankel's scheme there would be no problem. On the other hand, Uviller would also make it unprofessional conduct for the lawyer to reveal his personal doubts in the veracity of testimony or evidence; this time the alternative is compatible with

Freedman's view.^

0

Professor Uviller doesn't state how the lawyer should correct deceptive testimony without revealing his doubts in its veracity.

A different twist is provided by a reaction to Dean

Freedman's approach.^

1

Contending that the attorney client privilege applies only in a judicial context, the author suggest disclosure to the injured party. The author proposes an amendment to DR 7-102(B) to require the lawyer who discovers his client has perpetrated a fraud on another during legal repre-

42

Beall -4-3sentation to disclosure,that fraud to the injured party. Additionally such disclosure to the injured party shall not be subject to the duties in DR 4-101.

The characterization of exceptions to the rule of confidentiality is DR 4-101 could be those which protect the lawyer.

In Meyerhofer v. Empire Fire and Marine Insurance Co.^-'an attorney joined as a defendant in a lawsuit acted properly and within

DR 4-101 (c)(4) when he delivered to opposing counsel an affadavit which exonerated him from any liability. The affadavit was thirty pages long, and had sixteen exhibits.

66

The court concluded by stating that although the attorney could make the disclosure, he could not represent any other plaintiff in similar actions.

In a situation similar to that discussed in ABA Formal Opinion

*. MUftWAM ) «C _•» J by an attorney that he had given the client notice of an order to appear for trial was not protected, as it was not of a confiden-

69 tial nature.

7

Even if the testimony here was not confidential it was a "secret" for purposes of DR 101(A). It was not clear from the facts whether this testimony was compelled (see DR 4-101

(C)(2) )or made voluntarily; presumedly it was the former as the latter would violate DR 4-101(B).

The courts are fairly consistent in their requirements on the disclosure of material evidence in a case. One of the most prowi, inent cases, In rjs Ryder,

70

involved an attorney who actively concealed a shotgun and money from a robbery a client had committed.

43

1

Beall -4-3the court stated the attorney "should not be a depository for

72 criminal evidence..."' In Olwell, the attorney was in possession of a knife requested by the coronor in an investigation. The court acknowledged the claim of attorney-client privilege, but required the lawyer "as an officer of the court" to turn the knife over to the prosecution.*^ The court further provided that the attorney need not be disclosed as the source of the knife, so nL the client's privilege would be protected as much as possible.

The attorney's ethical dilemma of having a client who intended to perjure his testimony arose in Thornton v United

States.^ In that case the defendant (accused of murder) changed his defense to alibi when he learned of the prosecutions convincing evidence (this knowledge was gained through discovery).

The defendant's attorney moved to withdraw from the case for

"ethical reasons.""^ This motion was ultimately denied, and the defendant insisted upon testifying. The attorney called his client to the stand, announced to the court that the defendant was testifying against the advice of counsel, and then proceeded

77 to let the accused "tell his story. ' Contrary to the views of

Dean Freedman (discussed above), the attorney complied with

Defense Standard k-7.7

« On appeal of his conviction, the defendant argued this course of action amounted to ineffective assistance of counsel; the court was not impressed. The court's holding stated that a lawyer's obligation to his client must be considered in conjunction with "'moral and ethical obligations to the court, embodied in the Canons of Ethics of the Pro-

44

Beall -4-3fession. * T h e court praised the actions of the lawyer.

Without doubt, the most controversial dispute involving a failure to disclose facts and information by defense counsel occurred in 1974 at Lake Pleasant, New York. Two attorneys were appointed to represent the defendant in a murder trial; during their interviews with the defendant, the latter admitted guilt to two other murders unrelated to their case. The defendant described where the bodies could be found. The attorneys located the two bodies but did not reveal their location (or knowledge of the location) to anyone—police, prosecutors, or even one of the decedent's parents. During the trial of the case for which they were originally appointed, the defendant admitted guilt in the murder of the other two women; believing that the defendant had at that point waived his right of confidentiality the attorneys disclosed their knowledge of the loca-

79 tion of the bodies. Needless to say, the public was outraged by the "callousness on the part of the lawyers, whose conduct with the public interest and with simple decency." Dean

Freedman commented "not only did the two lawyers behave properly, but they would have committed a serious breach of professional responsibility if they had divulged the information contrary to their client's interest."

One of the two attorneys from the Lake Pleasant incident was criminally prosecuted for violation of public health laws requiring a prompt and decent burial of the dead, and a second

45

Beall -20statute requiring the prompt reporting of the death of a person.

82

The indictment was dismissed by the County Court without much consideration. The court felt the conflict of "the Fifth Amendment right, derived from the constitution on the one hand, as 00 against the trivia of a psuedo-criminal statute on the other.." must be resolved in favor of the attorney client privilege. On

84 appeal, the Supreme Court of New York affirmed. The appellate memorandum opinion starts out strong ("We believe that the attorney-client privilege...effectively shielded the defendant attorney from his actions which would have otherwise have violated the Public Health Law"); but it finished with a slight retreat:

"we note that the privilege is not all encompassing..." and the statement that lawyers "must observe basic human standards of decency, having due regard to the need that the legal system accord justice to the interest of society and its individual members."®

5

In light of their holding, the court's opinion would have had much more credibility if they had left out the part about observing basic human standards of decency.

It was in 1977 that the ABA Board of Governors created the

Commission on Evaluation of Professional Standards (hereinafter referred to as the "Kutak Committee")to reconsider "not only the of issues in ethical lawyering." On January 30. 1980 the

Kutak Committee released its discussion draft of the Model

Rules of Professional Conduct.®? Mr. Kutak announced the MRPC as "blackletter statements of the practice of ethical lawyering.."

Beall -4-3but at the same time he acknowledges "no rules...can dictate in

89 every case what the proper choice must be."

7

The main change in the MRPC from the CPR is a recognition of lawyers in different legal capacities: advisor, advocate, negotiator, evaluator, and an intermediary between clients. Each role has its respective rules of conduct, and the group is governed by basic rules in the lav/yer-client relationship.

Each role involves the attorney -client relationship, but the conflict of confidentiality and candor is most apparent in the lawyer's role as an advocate. The Preamble to the MRPC identifies the advocated responsibility to "diligently assert the client's position while being honest with the tribunal and showing proper respect for the interest of opposing parties and other concerned persons."^

0

Considered above the Preamble does not indicate a priority between candor and confidentiality; both recieve general support. However, when considered along with other code provisions and comments, it becomes apparent that the MRPC considers candor the more desirable choice. The chairman of the

Commission, Mr. Kutak, releasing the MRPC discusses a proposal to include in the MRPC a rea_uirement that the attorney in civil proceedings "must disclose facts, even if adverse, that would probably have a substantial effect on the determination of a

91 material issue."

7

Judge Frankel, a member of the Kutak Committee and presumedly the proponent of the required disclosure, lost on that issue, as the proposal was not accepted.

The principal section governing confidential information,

Rule 1.7 (see Appendix C), goes a step beyond its predecessor

47

B e a l l - 4 - 3 -

DR 4-101 in that Rule 1.7(h) has a mandatory disclosure required when it appears that the client will commit an act resulting in

92

"death or serious bodily harm to another person..."

7

Except for a change in form and a change in terminology, Rule 1.7(a) is roughtly the equivalent of DR 4-101(B), providing that the lawyer shall not "disclose information"—Rule 1.7(a), and the lawyer shall not "reveal a confidence or secret"—DR 4-101(B)—which is detrimental to the client. Both provisions have qualifying exceptions within their respective rule. Each rule also provides the lawyer may disclose/reveal certain confidences although the order of appearance is different.

The comments following Rule 1.7 seek to explain its purpose. Concerning disclosures adverse to the client, the Kutak

Committee examines a clients intent to harm another innocent party, the need to warn that innocent party, and the duty of confidentiality. They interpret Rule 1.7(b) to mean if "homicide or serious bodily injury is threatened by the client, the lawyer must make disclosure to the extent necessary to prevent the w r o n g . e m p h a s i s added) The Committee recognizes such a rule might prevent future clients from revealing their intentions, but prevention of harm to the immediate victim outweighs such a risk. The comment has guidelines for the lawyer to help him exercise his discretion under the "may" statute, but is (like the Ethical Considerations of the CPR) broad: "the lawyer's exercise of discretion requires consideration of the magnitude and

94 proximity of the contemplated wrong..."

7

48

.tsea±± j -

This writer's immediate response to Rule 1.7(b) is what constitutes "serious bodily harm"? If the MRPC were adopted in its present form, an attorney would presumedly be disciplined for violations of its provisions; as Rule 1.7(b) imposes a requirement for disclosure of serious bodily harm the definition of that phrase should be clear from the outset. It appears however, that a determination would be made after the fact (i.e. because the victim was hospitalized it is serious bodily harm), Secondly

"serious bodily harm" is relative: a broken nose is much more serious for a model than for a truck driver. Third, the rule would require a lawyer to become an analyst in divorce cases to determine whether the client is serious when he/she states they are going to get even with their spouse—or the attorney must disclose every threat made on the assumption that it might be serious. Last, in light of the public outrage of the attorneys actions in the Lake Pleasant incident, could the attorneys be disciplined under Rule 1.7(b)? The decedents bodies were not

"buried; they were hidden in the woods, but animals discovered one of the bodies. Is that serious bodily harm?

Rule 3.1 of the MRPC governs candor toward the tribunal.

J

The rule affirmatively requires disclosure of the presentation of false evidence, legal authority not known to the court, erroneous representations, and facts required to be disclosed

96 under the MRPC or by law. Dean Patterson, a consultant to the

Kutak Committee, felt Rule 3-1 would be one of the most widely di

97 subverted the importance of honesty in resolving disputes..." y

Beall - 4 - 3 -

Response to the MRPC discussion draft was quick and to the point. One commentator stated that DR 4-101 needed to "be strengthened, but the Kutak Committee, instead of strengthening it

"to make clear that the ethical rule controls over other laws requiring disclosure...go entirely in the other direction and make unethical the failure to disclose confidential information

98 where required by law."

7

The author, felt such a rule would be an "open invitation to legislatures or administrative agencies

99 to create statutes or regulations requiring disclosure."

7

The National Legal Aid Defender Association's (NLADA) position on the MRPC is in the same vein.

1 0 0

The NLADA contends

Rule 1.? does not "adequately preserve or safeguard the attorneyinroads on this basic right." Concerning the required disclosure of Rule 1.7(b) the NLADA does "not believe that information regarding anticipated acts of misconduct not involving serious physical harm should bp cause of the revelation of such a

1 02 confidence." Concluding, the NLADA urges the Kutak Committee to delete Rule 1.7(b) and (c) from the revision of the discussion draft.

103

Professor Andrew Kaufman questions whether the Kutak Committee could have gone further in Rule 1.7(b).

10Zj/

He acknowledges the caution of the Kutak Committee in hesitating to make an absolute judgment on disclosure of categorical issues, but nonetheless felt there were some areas in which there could be no doubt—such as a client's intention to bribe a judge.

105

50

Beall -4-3-

Kaufman's concluding remarks stress the discre-tion of the lawyer to make disclosure; he feels there is too much discretion, and therefore the rules could be "more precise about the nature of the adversary system.

10

^

The approach of the Kutak Committee is defended by Professor

Subin on the grounds that the ability of client confidentiality to encourage clients to discuss "damaging information" with their attorney in reliance of the privilege cannot be proved. Subin maintains that confidentiality is "not important enough to

107 offset the societal need to prevent harmful acts." He also notes with approval the fact that the MRPC creates a "broader public responsibility for the lawyer" at the expense of confidentiality.

108

Dean Monroe Freedman's reaction to the MRPC is predictable, but the depth of his feelings are surprising. He recognizes "an increased emphasis on putting the interest of society over the interest of the individual", and concedes the MRPC incorporates these views, but (not giving up) he responds "it's a very significant move toward totalitarianism. It makes the lawyer an agent of the state."

109

Responses to the MRPC have not come solely from individuals; organizations have reacted by proposing their own codes, or modifications of entire codes, as opposed to commenting on particular sections. One such group is the National Organization of Bar Counsel (hereinafter NOBC), comprised of counsel to state

110 bar associations. The NOBC produced a Report of recommendations

51

Beall -4-3following study of the MRPC. Their conclusion on the draft as a whole was to object to the change in format and structure of the CPR. The NOBC notes the development of case law under the

CPR, familiarity with its rules, current method of indexing of topics, economic cost of a change from one system of indexing to another, and the absence of ready identification of topic areas in the MRPC collectively make the MRPC in its current form objectionble.

111

The NOBC Report is the official position of the NOEC on the issue of ethics; their preference is to continue with the present format of the CPR, and make revisions where necessary.

The NOBC Report contains the suggested revisions of the CPR with amendments or revisions from the MRPC.

The NOBC Report recommends adoption of MRPC Rule 1.7Xb)

(rule requiring disclosure of clients intent to cause death or serious bodily harm to another), but it rejects Rules 1.7(a) and 1.7(c) as "they cover the same area as the present DR 4-101.

Additionally, DR 4-101 contains its own definition of 'confidence'

112 and 'secret', which is desirable."

The NOBC Report also proposes two "new" rules for Canon 4 of the CPR. Proposed rule DR 4-102 is actually Rule 6.2 from the

MRPC; it requires disclosure of information gathered by an attorney for the benefit of a third party evaluation) where the client has discharged the attorney. The

"evaluator" is a role of lawyers arising where the lawyer examines a clients legal affairs; if this evaluation is to be relied upon by third parties then it is an independent evaluation.

52

Beall -4-3-

The purpose of the rule is to prevent clients from misrepresenting their state of affairs to third parties.

11

^ Proposed Rule DR ^-103 governs vicarious disqualification of law firms in- order to preserve confidences of clients. This proposal is virtually identical to MRPC Rule 7^1• There are two changes made by the NOBC; one would require disqualification of the attorney leaving a firm, the firm he left, and any attorney with whom he subsequently becomes associated regardless of the degree of participation. The second change requires a waiver of disqualification to be in writing; the MRPC has no requirement of form.

J

Of the two proposed additions to Canon one (vicarious disqualification) is designed to protect client confidences, but the other, independent evaluation^ is equally committed to the concept of disclosure. The NOBC adopts MRPC 1.7(b), but in all other respects it keeps DR k-101 in the same posture. Due to the nature of the review by the NOBC (adoption or rejection of MRPC provisions) it is difficult to get an overview of the group's views on confidentiality and disclosure. The acceptance of MRPC Rule

1.7(b) would indicate a move toward disclosure— or at least a reluctance to strengthen the concept of confidentiality.

The Roscoe Pound-American Trial Lawyers Foundation pro-

11 6 posed a code to be a "viable alternative" to the MRPC. The

ATLA Public Discussion Draft is "principally the handiwork of

117 our able Reporter, Monroe H. Freedman..." Freedman's views are evidenced in the Preamble, which describes the adversary system as "the best method we have been able to devise to

53

Beall -4-3deterraine truth in cases in which the facts are in dispute."

11

®

The ATLA draft has as its first subject the "client's trust and confidences"; they propose two alternatives to govern confidentiality (alternative A is reprinted in Appendix D, alternative

B is reprinted in Appendix E).

1 1

^ The comments following the first subject heading define confidentiality in the broadest context possible: "any information obtained by the lawyer in

120 the course of the lawyer-client relationship." Both alternatives permit disclosure of confidences (phrased as "may reveal", not "disclose*), but neither require any form of disclosure.

Rule 1.1 (same in either alternative) requires the lawyer to of client confidences from the initial interview.

Alternative A's prohibition of breaching the confidences of a client is in Rule 1.2; it provides exceptions for disclosure when required by law (Rule 1-3)» when "necessary to prevent imminent danger to human life" (Rule 1.4), when the lawyer knows himself in an action (Rule 1.6). Alternative B places confidentiality in even higher regard than Alternative A (which is more protective of confidentiality than the CPR). Rule 1.2 provides that without consultation and consent from the client, a lawyer shall not reveal a client's confidence; exceptions are permitted for court order (Rule 1.3) and in order to defend against charges brought against the lawyer (rule 1.4).

12

3

Alternative B does not permit the lawyer to reveal imminent

54

Beall -4-3danger to the life of another, of the existence of bribery.

Neither alternative permits disclosure of the intent of a client to commit a crime, nor may the lawyer reveal a confidence to collect a fee: the lawyer's financial interest is not sufficient to justify impairing confidentiality.

12

^

Alternative A has been described as the traditionalist view of confidentiality; confidentiality is important but subject to exceptions. ^ Alternative B was described as the extremist view as it "admits of no circumstances in which a con-

1 fidence can be broken without the client's permission." The primary advantage of the ATLA draft over either the CPR or the

MRPC is its unqualified dedication to confidentiality; there would be few instances of indecision under this code. Its drawback is its narrow appeal; although designed with all fields of legal endeavor in mind, it is best suited for trial and courtroom applications.

The Kutak Committee acknowledged these adverse views, and on December 5» 1980 issued a clarification letter to explain

127 revisions of the MRPC draft which they would make. ' The indicated a revised draft of the MRPC would be released in May 1981, and

1 ? ft presented to the ABA House of Delegates in 1982. The letter dealt with four specific concerns of lawyers resulting from the MRPC.

The first concern was that the rules would jeopardize the adversary system. The Kutak Committee disclaimed any intent to change or impair the adversary system, and noted that broad

129 statements implying otherwise v/ould be eliminated.

7

The second

55

Beall -4-3concern related to client confidentiality; the Kutak Committee states (despite the confusion and indications to the contrary) that their intention was to strengthen the principles of confidentiality.

130

They note there is no rule to the effect that confidentiality is absolute, and go on the state there will be standards governing confidentiality which will require disclosure

(they will be specifically identified). Mandatory disclosures will be required for perjury, fraud in the course of negotiation, and crimes threatening life or serious bodily harm. There would also be permissive disclosure of crimes presenting a substantial threat of injury to the interest of another person. Mr Kutak closes the letter by admitting these were not the only areas of concern, they are mentioned because they received the greatest response on these issues.*

31

The question now becomes where does the legal profession turn now for a code of ethics. For uniformity, one code is much more desirable than competing standards: ethical conduct should not vary merely because an attorney moves from one jurisdiction to another. One problem which must be resolved is to whom does the attorney owe his allegiance; what is the attorney's paramount duty? Should the attorney serve the interest of society first, or should the client be protected even if the truth is not revealed.

Different proposed codes have different answers. Does the MRPC reflect the views of American lawyers in general — at least a majority of them -- and thereby provide an indication of the direction of ethical conduct, or is it merely the product of the

56

Beall -

4-

3-

Kutak Committee. Judge Frankel is a member of the Kutak Committee, his search for truth is well known. On the other hand,

Dean Freedman was the reporter for the ATLA draft; his contribution

<as admitted. While both men undoubtedly made significant contributions to their respective codes, it should not be suggested that their views were "railroaded" into the discussion

Irafts without consideratio

1

by the other members of the respective committees. The point to be made though, is that each code (including the CPR and the NOBC Report) is a reflection of the jerspectives of its authors. There is a desire to express the poper standard of conduct, but personal biases manage to influence that decision. For this writer, the "proper standard" for confidentiality would be that expressed in the HOBC Report; inclusion of MRPC Rule 1.7(b), and retention of the permissive disclosures in DR 4-101(0.

57

B

eall -2

0

-

APFSNDIX A

Canons of Professional Ethics

Canon 37.

It is the duty of a lawyer to preserve his client's confidences. This duty outlasts the lawyer's employment, and extends as well to his employees; and neither of them should accept employment which involves or may involve the disclosure or use of these confidences, either for the private advantage of the lawyer or his employees or to the disadvantage of the client, without his knowledge and consent, and even though there are other available sources of such information.

If a lawyer is accused by his client, he is not precluded from disclosing the truth in respect to the accusation. The announced intention of a client to commit a crime is not included within the confidences which he is bound to respect.

He may properly make such disclosures as may be necessary to prevent the act or protect those against whom it is threatened.

Beall

-3

7

-

APPENDIX E

Code of Professional Responsibility

DR 4-101

(A) "Confidence" refers to information protected by the attorney-client privilege under applicable law, and

"secret" refers to other information gained in the professional relationship that the client has requested be held inviolate or the disclosure of which would be embarrassing or would be likely to be detrimental to the client.

(B) Except when permitted under DR 4-101(C), a lawyer shall not knowlingly:

(1) Reveal a confidence or secret of his client.

(2) Use a confidence or secret of his client to the disadvantage of the client.

(3) Use a confidence or secret of his client for the advantage of himself or of a third person, unless the client consents after full disclosure.

(C) A lawyer may reveals

(1) Confidences or secrets with the consent of the client or clients affected, but only after a full disclosure to them.

(2) Confidences or secrets when permitted under

Disciplinary Rules or required by law or court order.

(3) The intention of his client to commit a crime and the information necessary to prevent the crime.

(4) Confidences or secrets necessary to establish or collect his fee or to defend himself or his employees or associates against an accusation of wrongful conduct.

(D) A lawyer shall exercise reasonable care to prevent his employees, associates, and others whose services are utilized by him from disclosing or using confidences or secrets of a client, except that a lawyer may reveal the information allowed by DR 4-101(C; through an employee.

59

Beall -37-

APPENDIX E

Model Rules of Professional Conduct

Rule 1.7

(A) In giving testimony or providing evidence concerning a client's affairs, a lawyer shall not disclose information concerning the client except as authorized by the applicable law of evidentiary privilege. In other circumstances, a lawyer shall not disclose information about a client which relates to the clientlawyer relationship, which would embarrass the client, which is likely to be detrimental to the client, or which the client has requested not be disclosed, except as stated in paragraphs (B) and (C).

(B) A lawyer shall disclose information about a client to the extent it appears necessary to prevent the client from committing an act that would result in death or serious bodily harm to another person, and to the extent required by law or the Rules of Professional

Conduct.

(C) A lawyer may disclose information about a client only

J

(1) For the purpose of serving the client's interest, unless it is information the client has specifically requested not be disclosed;

(2) To the extent it appears necessary to prevent or rectify the consequences of a deliberately wrongful act by the client, except when the lawyer has been employed after the commission of such an act to represent the client concerning the act or its consequences;

(3) To establish a claim or defense on behalf of the lawyer in a controversy between the lawyer and client, or to establish a defense to a civil or criminal claim or charge against the lawyer based upon conduct in which the client was involved; or

(4) As otherwise permitted by law or the rules of professional conduct.

60

Beall -37-

APPENDIX E

American Trial Lawyers Association

Client's Trust and Confidences Alternative A

1.1 Beginning with the initial interview with a prospective client, a lawyer shall strive to establish and maintain a relationship of trust and confidence with the client. The lawyer shall impress upon the client that the lawyer cannot adequately serve the client without knowing everything that might "be relevant to the client's problem, and that the client should not withhold information that the client might think is embarrassing or harmful to the client's interests.

The lawyer shall explain to the client the lawyer's obligation of confidentiality.

1.2 Without the client's knowing and voluntary consent, a lawyer shall not directly or indirectly reveal a client's confidence, or use it in any way detrimental to the interests of the client, except as provided in

Rules 1.3 to 1.6, and Rule

6 . 5 .

(Rules 1.3 to 1.6 permit divulgence under compulsion of law; to prevent imminent danger to life; to avoid proceeding before a corrupted judge or juror; and to defend the lawyer or the lawyer's associates from formally instituted charges of misconduct. Rule

6.5

permits withdrawal in non-criminal cases when the client has induced the lawyer to act through material misrepresentation, even though withdrawal might indirectly divulge a confidence.)

1.3 A lawyer may reveal a client's confidence to the extent required to do so by law, rule of court, or court order, but only after good faith efforts to test the validity of the law, rule, or order have been exhausted.

1.4 A lawyer may reveal a client's confidence when the lawyer reasonably believes that divulgence is necessary to prevent imminent danger to human life. In such a case, the lawyer shall use all reasonable means to protect the client's interests, consistent with preventing loss of life.

1.5 A lawyer may reveal a client's confidence when the lawyer knows that a judge or juror in a pending proceeding in which the lawyer is involved has been bribed or subjected to extortion. In such a case, the lawyer shall use all reasonable means to protect the client, consistent with preventing the case from going forward with a corrupted judge or juror.

61

Beall -36-

APPENDIX D (cont.)

1.6 A lawyer may reveal a client's confidence to the extent necessary to defend against formally instituted charges of criminal conduct, malpractice, or disciplinary violation brought against the lawyer or the lawyer's associates or employees.

Beall -37-

APPENDIX E

American Trial Lawyers Association

Client's Trust and Confidences Alternative B

1.1 Beginning with the initial interview with a prospective client, a lawyer shall strive to establish and maintain a relationship of trust and confidence with a client. The lawyer shall impress upon the client that the lawyer cannot adequately serve the client without knowing everything that might "be relevant to the client's problem and that the client should not withhold information that the client might think is embarrassing or harmful to the client's interests.

The lawyer shall explain to the client the lawyer's obligation of confidentiality.

1.2 Without the client's knov/ing and voluntary consent, a lawyer shall not directly or indirectly reveal a client's confidence, or use it in any way detrimental to the interests of the client, as the client perceives them, or as the lawyer reasonably understands the client to perceive them if there is inadequate opportunity for consultation.

1.3 A lawyer may reveal a client's confidence to the extent required to do so by law, rule of court or court order, but only after good faith efforts to test the validity of the law, rule, or order have been exhausted.

1.4 A lawyer may reveal a client's confidence to the extent necessary to defend against formally instituted charges of criminal conduct, malpractice, or disciplinary violation brought against the lawyer or the lawyer's associates or employees, but only when the charge, claim, or complaint is at the initiation or insistence of the client.

63

-ceaa.1

- j o -

FOOTNOTES

1

Patterson, A Preliminary Rationalization of the Law of

Legal Ethics, 5? N.C.L. Rev. 519. 528 ("197977

2 see ABA Code of Professional Responsibility DR 4-101(A).

(Hereinafter cited as~"UPR"J.

3

I n r e A, 276 Or. 225, 554 P.2d 479 (1976).

^ Id. at 554 P.2d 487.

5

ABA Commission on Evaluation of Professional Standards,

Model Rules of Professional Conduct (1980). (Hereinafter cTTed as "KRPU"") . —

^ Roscoe Pound—American Trial Lawyers Foundation, The

American Lawyer's Code of Conduct (1980). (Hereinafter cited as '" atla"

) . "reprinted at 16 Trial 44

(I98O).

? National Organizatior^f Bar Counsel, Re-port and Recommendations on Study of the Model Rules of Professional Conduct

(19«0). (-Kereinafter~cTEed as "NOBC Report). g

Letter from Robert J. Kutak, as Chairman of the Commision on Evaluation of Professional Standards, to Colleagues of the

American Bar Association (December 5» 1980). This letter was written to clarify the purposes and direction of the Kutak

Committee in their revision of the MRPC. As such, it will hereinafter be referred to as the "clarification letter."

9

ABA Canon 37-

1 0

Id.

1 1

M .

1 2

ABA Canon 41

G. Archer, Ethical Obligations of the Lawyer (Little,

Erown, and Company, BostonT lyio), aT~36.

14

1

Id., at 103.

ABA Comm. On Professional Ethics, Opinions, No. 91.

64

B

eall -

4-

3-

1 6

Id.

17

ABA Comm. Or! Professional Ethics, Opinions, No.s 155,

156 (19507.™" =========== — • =

18

Id., Formal Opinion 155-

1 9

M .

20 supra note 17. Formal Opinion 156.

21

H .

2 2

id.

23

4 1 4

c o m m o n

Professional Ethics, Opinions, No. 287 (1953i.

Id.

2 5

Id.

2 6

Id.

2 7

Kileski v. Locker , l4Misc. 2d 252,

I78N

.Y.S. 2d

911 (1958).

2 8

Id., at 178 N.Y.S. 2d 915.

20

' CPR, Preliminary Statement

3 0

Id.

31

CPR, Canon

32 supra, note 2.

CPR, DR 4-101 ( C ) .

^ CPR, DR 4-101(B).

3 5

CPR, DR 4-202 (D) . supra, note 34.

3 7

M .

O Q

"Attorney-Client Confidentiality; A New Approach,"

4 Hofstra L. Rev. 5^5" (1976) .

3 9

Id., at 687 sur>ra note

38,

at

688.

65

Eeall -40-

41

Frankel, The Search for Truth: An Umpireal View,

123 Univ. Penn. L. Rev. 1031,

1032

(197577

42

Id., at

1036.

4 3

M .

44

Id., at 1052.

Id., at 1057-58.

^

id.

47

Freedman, Judge Frankel's Search For Truth, 123 Univ.

Penn. L. Rev. 1060, (1975) •

= = = = =

48

M. Freedman, Lawyers Ethics in an Adversary System

(the Eobbs-Merrill Co., Inc., Indianapolis and New York, 1975) sit 3 •

4 9

Id., at 4.

5 0

see CPR, Dr 4-101(c)(3). supra, note 47 at 1064.

54

Freedman, Professional Reoonsibility of the Criminal

Defense Lawyer: The Three Hardest Questions, ~1>4 teich.L. Rev.

1469 (1966). = = =

55

Id., at 1482.

56 supra note 54, at 1477-78.

Id..

58

Uviller, The Advocate, The Truth, and Judicial Hackles:

A Reaction to Judge Frankel's Idea, 123 Univ. Penn. L. Rev.

I0F7 [19751.

= = = = = = = = =

5 9

Id., at 1074.

6 0

supra note 58, at 1080-81.

61

Client Fraud and the Lawyer—An Ethical Analysis 62

Kinn. _L. Rev. U9 0-977).

66

B e a l l - 4 - 3 -

6 2

Id., at 111-12.

6? supra note 6l, at 115.

64 see Levxne, Self-interest or Self Defense: lawyer

Disregard of the Attorney-Client Privilege for Profit and

Protection. 5 Hofstra L. Rev. 783 ("197777

6 5

497 P. 2d 1190 (2nd Cir 1974) cert, den. 419 U5

998 (1975).

6 6

Id., at 1195. supra note

65,

at

1196.

68 . , „ supra note

1 7 .

6q

United States v. Freeman, 519 F. 2d

67

(9th Cir. 1975).

7 0

263

F. Supp.

360,

Aff'd per curiam 381 F. 2d 713

(4th Cir.

1967).

71

71

64 Wash. 2d 828, 394 P. 2d 681 (1964).

72

Id., at 394 P.2d 684.

7 3

supra note 71 at 394 P.2d 684-85.

74 supra note 71 at 394 P. 2d

685.

7 5

357 A.2d 429, cert, den 429 US 1024 (1976).

7 6

Id. at 4-32.

77 see AEA Standard's Relating to the Administration of

Criminal Justice, The Defense Function, Section

7.7

7 8

supra note 75, at 437.

79 see Legal Bthics; Confidentiality and the Case of Rc

Garrow's Lawyers, 25 Buffalo L. Rev. 211, 220~Tl975T.

8 0

supra note 48, at 1.

81

Id., at 2.

8 2

People v. Beige

83

Misc. 2d 186, 372 N.Y.S. 2d 798 (1975).

8 3

Id., at 372 N.Y.S. 2d

803.

84

People v. Beige 90 A.D. 2d 1088, 376 N.Y.S. 2d 771

(1975).

67

Beall - 4 - 3 -

8 5

Id., at 376 N.Y.3. 2d 771-72.

86

Kutak, Coming; The New Model Rules of Professional

Conduct 66 ABAJ (193077"

Or; supra note 5-

88 suora note 86, at 48.

8 9

Id.

90

MRPC, Preamble: A Lawyer's Responsibilities, at 1.

^ suora note 86, at 49.

9 2

MRPC, Rule 1.7(b).

93

9 3

MRPC, Rule 1.?, Comment.

9if

Id.

9 5

MRPC, Rule 3.1•

96

VId.

Q7

71

Patterson, An Analysis of the Proposed Model Rules of

Professional Conduct,

31

Mercer L. Rev~ 645,

663 (198O).

98

7

Dooley, The ABA Model Rules: Why Legal Services Staff a n d

Clients Should Become Involved, 37 NLADA Briefcase 44,

W (1980).

9 9

Id.

100

Eisenberg, NLADA on the ABA Model Rules 37 NLADA.

Briefcase 49 (198077

1 01

Id. at 51-52.

102 supra note 100, at 52.

103 supra note 100, at 53•

104

Kaufman, A Critical First Look At the Model Rules of

Professional Conduct^ ABAJ loWT~1077 Cl930).

105

1 0

% d .

106 supra note 104 at 1073.

107

Subin, War Over Client Confidentiality: In Defense of the Kutak Approach, Nat'l L. J.', Jan. 19. 1981, at 22,23. col. 1.

68

1 0 8

Id. at 22.

1 0 9

110 supra note 7.

111

3.

112 supra note 7, at 76, comment to

113 supra note 7, at 34-35.

114 supra note 7, at 36.

^ i d .

116 . supra note 6, Introduction.

" ' i d .

118 supra note 6, Preamble.

119 supra note 6.

1 2 0

Id., Comment to Article I.

121 supra note 6, Rule 1.1.

122 supra note 6.

12

3ld.

124 supra note 6. Comment to Article

12

^supra note 107.

1 2 6 id.

127 supra note 8.

1 2 8

Id.

12<

>Id.

"Old.

" H d .

69

Beall -4-3-