submitted by The Centre for Education and Industry University of Warwick

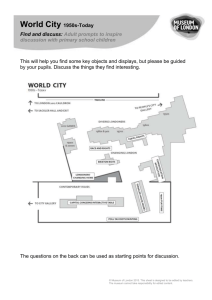

advertisement