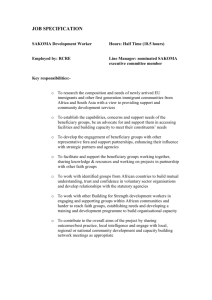

THE INSURANCE TRUST TEXAS LIFE

advertisement

THE LIFE INSURANCE TRUST IN TEXAS

DELI NDA EBElI NG

THE · LIFE INSURANCE TRUST IN TEXAS

The use of the life insurance trust in Texas as a means of estate

planning is somewhat unusual in that from looking at the cases, a life

insurance trust as such is seldom used.

In Texas as well as in other

jurisdictions, the distinction to be found is that life insurance has been

used as the source of a trust rather than having been created by the insured

himself as an express written trust.

Most of the cases which have arisen

concerning insurance and trust doctrines have done so on the basis of an

implied trust -- the insured takes out a life insurance policy and names a

beneficiary either with or without an understanding with that beneficiary

that the proceeds will be used to benefit a certain person or group.

So

while the insured intends to create a trust, he does not do so expressly,

and consequently, these matters, usually within the family, wind up in the

courts to determine exactly who is entitled to enjoy the proceeds of the

insurance.

The cases in Texas in particular have generally followed this line of

facts, and as a

res~lt,

the courts have not dealt with all of the potential

questions that can arise in such a situation unless their failure to deal

with them indicates a rejection of those problems.

For example, the court$

never seem to speak of a trust as being inter vivos or testamentary, yet the

tones and holdings in the cases appear to indicate that the trusts found

are inter vivos and not testamentary -- it is simply an issue to which the

courts have not directly spoken.

For this reason and others, it is necessary

to more fully explore the area by looking at some of the decisions in other

jurisdictions involving similar cases.

Some of the courts do take different

approaches to reach comparable solutions, and some of these ideas might well

extend into Texas law.

There is no longer a problem as life insurance has been established as

property by the Texas legislature, thus making it clear that it is something

which can be used by an insured in either planning for his family or business.

Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann. Art. 23(1) (1969). But this will not solve all the

dilemmas in determining exactly what the nature of life insurance is.

Under

the same statutory definition,an insurance policy is said to be a chose in

action which matures at the death of the insured.

696 (1963).

Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann.

~rt.

Brown v. Lee, 371 S.W.2d 694,

23(1) (1969).

Clearly, a life

insurance policy holds nothing for the beneficiary until the insured dies,

but this does not make it any less certain as a -potential trust res.

The fact that the trust dealt with a contingent interest of the insured

in the certificate of insurance is of no moment. That interest

became vested at the death of the insured, and, the beneficiary having

collected the insurance money, the trust, under the agreement creating

and acknowledging it, attached to the fund. A trust of this character

is not to be distinguished from assignments of contingent interests,

which courts of equity recognize as valid. Hirsh v. Auer, 146 N.Y. 13,

40 N.E. 397,398 (Ct. App. N.Y., 1895); and Rape v. Gardner, 54 S.W.2d: 594,

596 (Te-x. Civ. App.-..Eastland, 1932), reh. den.

Other courts have regarded life insurance as a mere contingent interest

but have said that the :- beneficiary is not without power to deal with the

interest or· that he cannot enforce it in equity when it does become vested.

Kerr v: Crane, 98 N.E. 783,784 (5. Jud. Ct. Mass.1912).

been hel d that

e\'en ~

Further, it has

though the proceeds are not payabl e unti 1 the death of

the insured, the trust will not be testamentary; even better, insurance trusts

will be upheld though not executed with the

Ballard v. Lance, _6 N.C. App. 24, 169

S.E~

formalitie~of - a

will.

2d 199, 202 (C.A.N.C. 1969).

The

rationale for such holdings is so obvious that most courts never bother to

state it; life insurance by its very nature can be personal property of the

insured only upon his death, and any claim that proceeds are testamentary

simply does not comport with logic.

-2-

The Texas statute s~ems to avoid the problem of whether an inter vivos

trust is testamentary.

None of the Texas cases dealing with life insurance

trusts have invalidated them on the basis of being testamentary as a few

jurisdictions have done.

But the Texas trusts have generally not been dependent

upon wills, and the courts have simply found that the dispositions were made

during life, and while intended to be effective upon death, they had not

become testamentary, primarily because of the nature of insurance itself

there

is no interest in a beneficiary until the insured dies, thereby leaving no

interest which can be presently enjoyed.

However, for a conflicting view

holding that rights,to proceeds to a beneficiary does not arise from the

death of the insured but rather from the contract when taken out, see

Union Trust Co. of Pittsburg v. McCaughn, 24 F. 2d 459 (E.D.Pa. 1927),

apparently contrary to the general view that the beneficiary has no rights

under a life insurance contract when the insured has power to change the

beneficiary.

Probably the best view stating that such a trust is not testamentary was

expressed by a Florida .court:

By the nature of life insurance contracts, the major benefits to be

derived therefrom do not accrue until the death of the insured.

Merely because this was the nature of the trust res, the trust should

not be considered testamentary. As we have pointed out above, the

interest which passed to the trustee under the trust instrument was

substantial and imposed a clear-cut duty on the trustee. Furthermore,

the trust had a substantial existence during the life of the settler and

should not be considered testamentary. In ReEstate of Herron, 237 So.

2d 563,568 (Fla. D.C. App. 1970), reh. den; ' Res. 2d Trusts, § 57.

A common purpose for applying the trust doctrine to insurance proceeds

aris~in

situations where a person desires to protect a minor child or

relative, and many of the Texas cases have come before the courts under

these facts.

One of the earliest cases, Clausen v. Jones, 18 Tex. Civ. App. 376,

-3-

45 S.W. 183 (Tex. Civ. App.

1898), applied the trust theory very strictly.

There the husband had made the second wife and children of a prior marriage

beneficiaries in a life insurance policy issued by a fraternal organization

and had later changed the designation to the wife as the sole beneficiary.

When the husband died, the children claimed that their father had changed

the beneficiary of the policy only for convenience in collection of the

pol icy and that the second wife was only to coll ect t\'.ro-thi rds of the proceeds

in trust for the children.

The wife denied that this had been her husband's

wishes but agreed to carry it out if the court found a trust existed.

The

lower court did not, and it further rejected allegations by the children to

the effect that the wife was a "mean stepmother".

In its holding, the

appellate court held the wife to a very limited trusteeship in that she was

only a trustee to collect the proceeds, and it agreed that the lower court

was correct in omitting the evidence regarding the mother's treatment of

the children.

However, the court made it quite plain that a further duty

would be found had the wife's trusteeship been extended further to hold and

use the proceeds for--the children.

Absent such a duty, there was basically

no revi ewab1 e conduct for the court to examfne.

184.

C1 ausen v. Jones, supra ,at

The case was reversed to the extent that a requested charge should have

been given to the effect that the deceased could make a provision for the

children to share in life insurance proceeds, and it therefore appears to be

an issue of fact to determine what portion and what funds may be used to

satisfy the insured ' intent.

Clausen v. Jones, · supra ,at 185.

In discussing a life insurance trust, it is essential to examine first

the requirements in creating such a trust.

In the first instance,

most of the

life insurance trusts which have reached the courts have been the result of

statements made by an insured to another person regarding his intent, and

-4-

the issue then becomes whether or not a trust can be created in life

insurance or in the proceeds by parol ev idence since no written documents

generally evidence the parties' intent.

The courts have been positive in declaring that a trust can be created

in any kind of personal property and may be proved by parol evidence.

Allen v. Withrow, 110 U.S.119, 130, 3 S. Ct. 517, L.Ed. 90 (1884); Eaton

v. Husted, 172 S.W.2d, 493,497 (Tex. 1943) reh. den; Brault v. Bigham,

493 S.W.2d 576,578-79, (Tex.Civ.App. -- Waco, 1973), reh. den.; Ballard v.

Ballard, 296 S.W.2d, 811,816 (Tex.Civ.App.

Galveston, 1956); Rape v. Gardner,

supra, at 595; Haberland v. Haberland, 303 F.2d, 345,347 (3rd Cir. 1962),

reh. den.; Fahrney v. Wilson, 180 Cal. App.2d, 694, 4 Cal. Rptr. 670-673,

(D.C. App. 1960), reh. den.; Rosen v. Rosen, 167 So.2d,70,72 (Oist. Ct.

App. Fla., 1964); Crews v. Crews' Admin. 113 Ky. 152, 67 S.W. 276 (Ky. Ct.

App. 1902); Cooney v. Montana, 196 N.E.2d, 202,206 (5 Jud. Ct. Mass. 1964);

-

and Hirsh v. Auer, 146 N.Y. 13, 40 N.E. 397 (Ct. App. N.Y. 1895).

The standard necessary to uphold a parol trust has not been seriously

disputed.

The

Fahr~ey

court, supra, at 673, said that the evidence to

establish a parol trust must be clear and convincing, especially where the

declarant is dead, and this is a matter for the trial court's determination,

not to be upset if the evidence is sufficient.

The court went on to say

that the proof could be indirect, i.e. through acts, conduct, or circumstances,

and that words such as "trust" and "trustee" were not necessary if the intent

were otherwise clear.

.By requiring a "clear and convincing" standard, the

danger is averted that the court will be enforcing a bare promise to

give or will by completing an otherwise incomplete gift.

116 F.2d, 1017, 1018 (2nd Cir. 1941).

-s-

Cullen v. Chappell,

Probably the most definitive statement

I

was made by the United States Supreme Court in Allen v. Withrow, supra, at

129-30,

where it was said:

So far as the personal property conveyed to Withrow is concerned, it

must be admitted that a trust may be established by parol evidence;

but such evidence must be clear and convincing, not doubtful, uncertain,

and contradictory, as ill this case. The evidence must consist of

something more than loose conversations with third parties. The

declarations of the grantor relied upon must be made at the time of his

conveyance or while he- retains an interest in the property, and be so

connected with the conveyance as to justify the conclusion that it was

-made or is held in execution of the purposes declared. Declarations of a

purpose to create a trust not carried out are of no value, nor are

direct promises to that effect unaccompanied with considerations turning

-them into contracts.

Most of the cases -which have found a. trust have been based on more than

idle conversations where the insured took out the policy, at the same time

expressing to the beneficiary that he was taking the policy for the purpose

of protection of some third person or by expressing to an employer or a

friend that he was taking certain action for a certain purpose.

In this

regard, the parol evidence is a matter for the trier of fact to judge since

that person or persons is best able to pass upon the credibility of the

witnesses, a task which the appellate court is by nature unable to perform.

E-ven -though a trust can be created if!

thi~

still be found in order to validate a parol

and Trust Co., 195 N.E. 2d 862

manner, certain elements must

trust.

Payy v. Peoples Bank

(Ind. App. Ct. 1964), reh. den.

be an expressed purpose of the trust.

There must

The Supreme Court of the United States

in Allen v. Withrow, supra,at 130, briefly discussed this problem, though the

thrust of the case was directed toward a trust in real property rather than

personalty.

There the court made a statement that "(d)eclarations of a

purpose to create a trust not carried out are of no value, nor are 9irect

promises to that effect unaccompanied with considerations turning them into

contracts."

Allen v. Withrow, supra,at 130

-6-

The court seems to be saying

that the mere expression of a trust purpose will not be sufficient in itself

to create a trust in personalty without some form of consideration.

However,

in the usual situation, it is hard to determine exactly who is giving

consideration.

On the one hand, the settlor creates the trust and receives

in return a promise from the beneficiary to carry out his intent at his

death.

Kerr v. Crane, supra, at 784, but this has problems inherent in it

from the outset since courts are divided as to whether the beneficiary must

know that he is to be the trustee, the majority holding that he does not

have to have such knowledge.

On the other hand, in creating the trust the settlor is giving

consideration to the beneficiary by making him the recipient of the

insurance proceeds at the settlor's death.

The Clausen case, supra, is a good example of this principle.

The

Texas court seemed to be grasping to find that a trust had been created,

and no trust purpose was expressed at all -- the husband had merely changed

the beneficiary from the second wife and children to the second wife.

court, though

holdiD~

The

the wife to a limited trusteeship, nevertheless found

that the "purpose" of the trust was the collection of two-thirds of the

proceeds for the children.

Possibly the court was exercising its equitable

powers in thinking that the children were the natural objects of the father's

bounty; however, the opinion does not show any evidence upon which the court

might have reached its result.

Another question is how expressly the purpose must be stated.

The

general trend has shown the expression of purpose not to be written in the

policy but orally

in statements from the insured to another person .

One of

the most notable Texas cases is Eaton v. Husted, 172 S.W.2a: 493 (Tex. 1943),

reh. den.

~7-

The facts of the E~ton case make it one of the most interesting on

the subject, and because of their relevance, they are worth recounting.

The plaintiff was an illegitimate child who lived with her grandmother in

New London, Texas, until she was five when she was taken from that part of

the state due to her grandmother's illness and inability to care for her

anymore.

At that time, a family conference was held to determine what was

to be done with the grandmother, and a son agreed to take her into his home,

but he refused to take the little girl because of the influence he thought

she would have on his children as an

waif that no one ·wanted.

ill~gitimate

child -- the picture of the

Finally, the half-sister of the plaintiff's mother

agreed to take her, and plaintiff did not see her grandmother again nor the

members of her mother's family for many years.

She subsequently married and

moved to California and lost track of any family.

Plaintiff's contacts with

her family were rekindled in 1937 when she heard a news report of the New

London schoolhouse explosion.

Concerned that members of her family might

have been among the injured or killed, she wrote to the sheriff to see what

she could learn, and." as a result, ·she eventually brought suit in 1941.

Plaintiff had learned that her grandmother had settled with all the members of

her family except plaintiff's mother who had died after her birth, and the

grandmother refused to leave to live with her son until he would agree orally

to manage her estate for her benefit during the remainder of her life and

then for the plaintiff's benefit until she was twenty-one, at which time she

was to receive the property.

Plaintiff alleged that under this oral trust

agreement, the grandmother deeded two tracts of land, a bill of sale to her

personal property of furniture and ten promissory notes, and a life insurance

policy to be administered under the trust, but she alleged that she had not

brought an action for enforcement earlier because she had no knowledge of

the facts.

She further ·c1aimed that the son accepted the terms of the trust

as trustee and never repudiated it.

She sought to recover one-fifth of

all the properties under the trust because the trustee had so commingled

the property as to not be able to distinguish what should have been hers.

Other heirs of the grandparents did not deny that a trust existed but

cross-claimed that it existed for the benefit of all heirs.

Without going into all of the complicated determinations as to the real

estate, the lower court decided that the trust did extend to all other heirs

living at the grandmother's death and found that the trust existed on the

real and personal property until plaintiff was twenty-one.

Plaintiff was

given a one-eighth interest in two tracts and an undivided one-eighth interest

in oil royalties.

The Court of Civil Appeals at Texarkana affirmed the

judgment except for the judgment against a non-resident defendant, and

the defendant appealed, but the Texas Supreme Court affirmed.

The primary issue on appeal was whether the court was justified in

finding a parol trust instead of a simple agreement to manage the property.

The court found that-·-t.here definitely was an expressed purpose of the trust,

sUbstantlated by the testimony of several witnesses who testified that the

grandmother remained concerned until she died that plaintiff would get her

share of her property as she wished and testified that the son agreed to

carry out this purpose.

The court also found the element that the United

States Supreme Court looked for in Allen v. Withrow • . supra. that is,

consideration; the bill of sale for the grandmother's p.e rsonal property

included the life insurance policy. and it was recited that the transfer was

made "for value received."

Eaton v. Husted, supra, at 496.

The defendant

claimed that the life insurance policy was not under the trust because it was

issued by an organization which no longer existed and the records of which

had been lost so that the grandmother made the son the beneficiary to collect

the proceeds.

However, the trustee's brother testified that the insurance

had been expressly listed by the grandmother as a part of the trust, and the

court also found that it was very significant that the son was made the

trustee of the policy at the same time the other property was deeded to him,

regarding these facts as evidence that the policy was part of the trust and

was accepted by the trustee as such.

interesting twist concerned the land.

Eaton v. Husted, supra, at 497.

Another

There was testimony to the effect

that the trustee told a friend that he had $900 of the insurance money buried

in a fruit jar in the garden, and the evidence also showed that one of the

tracts of land that the trustee brought was paid for with $900 cash.

Of

course, the court did not say that the story was true or not true, but it

merely said that the jury believed the story, impressing part of the land with

the trust as a result of a type of tracing theory.

Another element besides the

e~pression

of a trust purpose is the

expression of the subject matter of the property to be impressed with a

trust.

GenerallY,~his

has not been the element which causes the problems

since in the cases concerned with life insurance proceeds, the insured, if he

said anything whatsoever about a trust, said that he was buying the policy

as the res of the trust.

A third element is that the objects or beneficiaries must be determinable.

In the Eaton case, the plaintiff-granddaughter was clearly intended to be the

beneficiary of the grandmother's trust since the grandmother was so worried

that the plaintiff should have her mother's share in the property.

have been other cases where this element was the one in question.

But there

The

courts apparently will look at the beneficiary or object of the trust to

determine if that person is indeed the one who should be benefited.

An often cited Pennsylvania case is illustrative of this problem.

Donithen

v. Independent Order of Foresters, 209 Pa. 170, 58 A. 142 (Pa. 1904).

In that case the husband had a policy from a fraternal order for $1,000

with his brother listed as the beneficiary.

The wife, at her husband's

death, claimed that the brother was trustee for her, but the brother claimed

the proceeds for himself.

The wife claimed that the payment to the brother

was in contravention of the policy to protect the widows and orphans of its

insureds first.

The court agreed with the wife that a parol trust existed

on the proceeds because of testimony indicating that the husband had

expressed his wishes that the proceeds would take care of his wife and pay

the outstailding debts if anything should happen to him.

The court, in

reaching its decision, looked at the circumstances of the parties,

Donithen v. Independent Order of Foresters, supra, at 143, and its statement

is indicative of the trend where the issue of a proper object of the benefit

is in question:

Was it probable that the thoughts of this young husband,

engaged in a hazardous employment, would turn to making a

money provision for this brother--~ould prompt him to take

upon himself the annual burden of payment of dues on a

$1000 certificate the remainder of "his life for the sole

benefit of this brother, who was not necessitous, to the

exclusion of his young wife, Who he knew in case of his

death would be?

It was concluded by the court that the husband had put the policy in

his brother's name because he was more established and experienced in

business than his wife who was still very young, and the evidence indicated

that he did not trust his wife's mother with the money and that the brother

would be in a better position to pay the debts of the parties so that the

wife would not lose their home and other property.

Basically, the court

looked at the facts of the case to determine that it was not reasonable that

-11-

the husband should prefer to provide for another person when the logical

object of his affection and bounty would be in need.

A Texas

Ballard v. Ballard, supra, is an important case

case~

representing the same principle.

The father and mother had been divorced

a short time earlier, and the father changed his group insurance policy

into an ordinary life insurance policy when he left his :employment.

When he made the change, he made his brother

beneficiary~

stating to

several individuals that he knew the brother would see that his little

girl was cared for.

The brother never told the wife of the money he

received, and she brought the suit for her daughter when she learned of the

policy several years later.

The brother's attorney said that the policy

had been left to the brother "with instructions", and the word "trust"

was never used to describe the relationship.

The brother disclaimed any

knowledge of a trust or that there had been any condition to his being

mmed beneficiary.

fact

exist~

property

The court, however, in determining that a trust did in

looked at the family situation, the brother's salary, his

holdings· ;<.,. ~nd

in particular at the fact that the insured owed no

debts to his brother that the policy could be deemed to be repaying, and

essentially, the court placed the burden on the brother to justify his

being beneficiary of the policy.

In holding that this burden had not been

met, the court stated:

Mr. Ballard (brother) developed no relationship between himself

and his deceased brother -- or any other fact -- which would

tend to explain why his deceased brother would have undertaken

the payment of premiums on the $13,000 policy for the purpose of

providing a fund for Mr. Ballard's benefit to the exclusion of

his own infant daughter. Ballard v. Ballard, supra, at 815.

The court even went so far as to determine that it was "unnatural" for

a father to provide for his brother and not his daughter and found that

-12-

the father had in mind a living, active trust for his daughter's welfare,

and if not an active trust, then a dry passive trust to collect the

proceeds for the daughter's benefit.

819-20 .

Ballard v. Ballard,supra, at

Hence, it- appears that before a court will allow a beneficiary

of a policy to collect and use the proceeds for himself, it will first

look to see if that beneficiary is a natural object of the insured's

bounty or whether someone else, such as one contesting the beneficiary',s

right to the proceeds, is a more appropriate person to be benefited by

the funds.

A slightly different problem can arise when the named beneficiaries

are natural objects of the insured's bounty, but suit is brought to expand

the class.

This was the situation in Ballard v. Lance, 6 N.C. App. 24,

169 S.E. 2d 199 (C.A:N.C. 1969), in which the deceased purchased flight

insurance before leaving on a plane trip.

space in which to list two beneficiaries,

On the form there was only

~nd

the record showed that it

had been her practice to name different grandchildren each time.

laughi~gly

She

selected. two names and put them ' in the spaces, at the same

time telling her daughter that should'anything happen to her, she wanted

the two named beneficiaries to share in one-half of the proceeds and the

other grandchildren to share in the other half.

The plane did crash, and

the grandmother and one of her grandchildren were killed.

The lower court

determined that a trust in law had arisen and declared that the two named

beneficiaries held half the proceeds in trust for the other grandchildren

and held that the plaintiff as guardian

of the two beneficiaries held that

half of the proceeds as trustee for them as minors.

In affirming, the

appellate court held simply that a trust was created under the oral

statement of the grandmother to her daughter and that a trust could be

created without any mention of it in the policy

at 202

Ballard v. Lance, supra.

Neither did it affect the outcome that the trustees were minors.

The court does not answer the question of how minors are to carry out the

functions of trustees, but presumably their functions would be controlled

by a guardian or a co-trustee.

Thus, the case indicates that the class

of persons intended to be benefited could be extended beyond named

beneficiaries when a parol trust could be established by the evidence.

The fourth element that is necessary to establish a parol trust

is expression of the manner in which the trust is to be performed . .{Pavy.~ supra,

aL·.366.)

The case of Burgess v. Murray, 194 F. 2d 131 (5th Cir. 1952L

reh. den4 is a good example of this principle.

The husband set up a life

insurance policy, designating his father and sister as beneficiary and

contingent beneficiary respectively.

He then wrote a letter to his father,

explaining that the father was to take care of his children if he should

die and

u~e

the proceeds in case of sickness or other emergency; if there

were no emergency needs, the proceeds were to be saved to be used for the

children's educafi·on.

The father died, and the sister became the

beneficiary, claiming the proceeds for herself upon the husband's death.

His wife sued to have the sister declared a trustee, but the sister denied

that the letter in question created a trust or that it was intended to

apply to her.

In short, the court held that it did establish a trust and

that the proceeds should be given to a guardian who could qualify, i.e. the

wife.

Clearly, the trust had a purpose .in providing for emergencies and

subsequent education of minor children; the beneficiaries were certain, but

the court had to use its equitable powers to compel the trust's enforcement;

the court found that it was definitely the proceeds of the policy which were

to be impressed with the trust; and finally, the method of carrying out the

_-14-

terms of the trust was definitely set out by the insured that disbursements

should only be made upon certain contingencies.

An interesting question was brought up by a defendant in a

Massachusetts case' Cooney v. Montana, supra, where -the sister was named

as beneficiary of a life insurance policy by her brother who told her that

the proceeds were to be spent primarily for education.

The lower court

ruled that the money belonged to the sister to do with as she chose, flee

of trust, and that she was bound by no legal obligation, though perhaps by

a moral one.

Cooney v. Montana, supra,at 204-5.

Because the brother had

died accidently, the policy paid double indemnity, and the sister had

kept the $10,000 amount he had requested in a safety deposit box in the

bank in cash but had used the remainder for her own purposes and had kept

no records.

Her supposed obligation was to provide especially for two

younger children, one of which was in a hospital school,and a third who

was in need

of the

funds for educational purposes.

Finally, the sister

disclaimed any responsibility for the children and chose to have nothing

more to do with them.

In line with most jurisdictions, the appellate

court reversed the lower court, holding that there had been a trust

established, yet the moral obligation theory is certainly one that a

defendant would want to argue in trying to retain proceeds for himself.

However, in view of the majority of the decisions, this would not be

profitable for the beneficiary.

Further, the beneficiary might encounter

the result that the beneficiary/trustee did in Cooney,who was removed

from her position.

The court determined that because the husband had

given his instructions expressly to the sister and explained how he wanted

the money used, it was therefore his intent that the sister use none of

the proceeds for herself, assuming that it would be the minimum recovery

-15-

of $10,000. Cooneyv. Montana, supra, at 208· Under these circumstances,

the sister accepted the trust and did not repudiate it and was therefore

under an obligation to use reasonable skill, prudence, and judgment,

including a duty to keep accurate records.

at 208:

"Cooney v. Montana, supra,

Because the sister was not performing the duties the father

had entrusted in her and because she was allowing the money to sit in

the bank earning no income, she was removed, and the cause was remanded

to the lower court to appoint a new trustee.

It seems inevitable that at some time a court will find that

a trust has not been created for one reason or another.

Any trust which

does not meet the requirements set out will fail automatically because

there must be a degree of definiteness and certainty in the formation of

a trust, whether oral or written. Pavy v. Peoples Bank and Trust Co.,

supra, at 866.

\·Jhile the result of the case was to invalidate the

attempted trust, the courtls reasoning is a little less clear.

The

court set out the requirements of a parol trust already discussed and

went on to say -that the trust here failed because it did

~ot

meet those

elements -- changing the beneficiary was of itself i"nsufficient to

create a trust.

Pavy v. Peoples Bank and Trust Co.,- supra, at 867.

The bank had not known it was to be the trustee; thus there were no

trust terms stated either in the policy or in the instrument changing

the beneficiary.

The court concluded that the trust could not be valid

apparently on the basis of the will

tha~

the insured subsequently

executed as it made no mention of any life insurance policy or to the

instrument changing the beneficiary, and therefore, the so-called inter

vivos trust and testamentary trust could not be related.

But the court

still had to do something with the proceeds, and it stated the

-16-

"elementary" rule that where a person attempts to create an express

trust and fails, a resulting trust arises in favor of the settlor or

his estate, and the property concerned, here the policy proceeds,

reverted to the estate so that the creditor was allowed to take his share

from the estate . . Accord, Union Ttust Co. 6f Pittsburgh v. McCaughn,

24 F. 2d 459 (O.C.E.O . Pa. 1927).

The Pavy case, though not binding on Texas courts, is still

somewhat puzzling .

When compared with other cases which seemingly had

no difficulty in finding that a parol trust existed with no more facts

than this case.

It is a bit difficult to reconcile the decision of

this court that the inter vivos trust had to relate to the testamentary

trust found in the will.

The court, in its opinion, does not indicate

that there was any intent by the deceased that the insurance trust be the

same as the testamentary trust in the first place.

Even if one looks at

the four elements the Pavy court sets out, there seems to be no reason

why all four cannot be found in the facts; the purpose of the trust

was implied in ·h·is concern for his wife's ability at that time to manage

the proceeds; the subject matter obviously was the proceeds since he

executed the change of beneficiary instrument; he clearly set out the

bank as the beneficiary and the instruments set out the manner in which

the trust was to be performed, i.e. for the benefit of the wife.

was clearly not intended to be a testamentary disposition.

This

He had

established the policy much earlier and changed the beneficiary upon the

wife's illness, not in anticipation of his immediate death, which mayor

may not have been contemplated at the time.

The fact remained that he

had set up an inter vivos trust by the execution of the instrument

changing the beneficiary, and it was not necessary to do so with the

-17-

formalities of execution of a will.

It would seem that the court was not

justified in determining that because the proceeds were large and the

remaining estate was small that the deceased could not have been

intending to create a trust from the smaller portion of the estate, or

at the least, that the insured was trying to incorporate the trust

under the will by reappointing the bank as its trustee .

Undoubtedly,

both sides of the arguments have flaws in them, but in general, it would

not appear that the Indiana court is in line with many of the

jurisdictions, including Texas . . .

A Florida court took a contrary view, stating that not having

trust terms · set out will not justify a court's modification of the

contract.

Rosen v. Rosen, supra, at 72 .

While the Pavy instrument

omitted any terms of the trust other than that the bank was to be

trustee for wife, the Rosen policy omitted any mention of a trust in

any document.

The insured had set up two policies with his minor sons

as beneficiaries, later changing the beneficiary to his father.

At

his death

th~

proceeds~

arid the court, finding a trust, declared that the proceeds

father and the guardian of the children both claimed the

were not to be paid to the beneficiary but to the guardian.

Rosen, supra , at 72.

Rosen v.

The appellate court agreed that there was a trust

but said that proceeds of a policy can only be paid to the named

beneficiary.

to step in

~nd

To authorize the payments to the guardian was for the court

change a contractual arrangement between the parties,

something that could not be done.

Rosen v. Rosen, supra, at 72.

Here

there was even less evidence that the insured intended to establish a

trust, but the court still found that from the circumstances this was

his intent, yet the Pavy court so modified that contractual agreement as

-18-

to invalidate

it~ '

obviously two opposites in interpretation of the

instrument . . Contrast the court1s holding that the proceeds had to be paid

to the named beneficiary with the holding in Burgess v. Murray, supra.

There the court ordered the .proceeds to be paid to the mother rather than

to the insured's sister who had been named as beneficiary.

The court's

reasoning was that the husband's intent could best be carried through by

the wife as the guardian and mother of the children in seeing that the

education of the children was accomplished with the funds.

Murray, supra, at 132-33.

Burgess v.

What the court did was a tacit removal of the

sister as trustee as a part of its equitable powers.

Several different types of problems have arisen under conflicts

resulting from change of beneficiary under the life insurance policy,

generally resulting in a claim by the new beneficiary that no trust was

ever expressed or implied.

In Re 'Koziell's Trust, 412 Pa. 348,194 A.2d 230

(Pa~

1963),was a

situation in which the husband changed the beneficiary of his life

insurance policy from his wife to his sister.

The wife at the husband's

death petitioned the court to require that the sister should establish

either a guardian or a trustee for the children of insufed and wife, and

her request was based on her statement that her husband had named his

sister beneficiary of the policy in consideration of her promise to use

the proceeds for the childrens' benefit

Kozie11's Trust, supra, at 231.

There would never have been a problem at the outset because the sister

said at the time of the husband's death that the proceeds belonged to

the wife and children, so in reliance the wife called the insurance

company and reported the conversation, and they prepared waivers for

the sister to sign.

However, by that time, her avarice had apparently

-19-

taken over, and she refused to sign the papers, claiming the proceeds

instead for herself.

The husband's superior testified at the trial that

he had not known how the situation was to work, but he knew that the

husband had said that he wanted his sister to have the money for his

children.

But at trial

the sister denied having ever disclaimed her

right to the proceeds.

The lower court dismissed the wife's action, finding no agreement

between the insured and his sister that she would be trustee, basing

its decision on a case which said that the trustee's declaration could

not be sufficient to establish a trust.

Koziell 's Trust, supra, at 232.

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania rejected the decision of the lower

court

for the reason that it found that there was much more evidence

than the so-called statement of the trustee upon which to

rely~

and it

distinguished the case relied upon as one that referred to a parol trust

in reality.

Consequently~

"the court remanded the case as it could make

no judgment on the credibility of the

witnesses~

the determining factor

in the case. "AJready it is" indicated that change of beneficiary problems

as shown by the Koziel; case and the Texas cases, infra~ crop up when the

beneficiary is changed" from a wife or husband or another person very

close to the one intended to be benefited to another person, usually a

collateral relative who does not feel the obligation of carrying out the

insured's wishes.

When this type of thing

happens~

one should look

behind the monies of the beneficiary for evidences of fraud,

deceit~

or

willful misconduct.

Some of the Texas cases present some unusual problems, but

later cases appear to reconcile any difficulties by finding no conflicts

in the authorities at the outset.

One of these cases is Olivares v.

-20-

Olivares, 170 S.W.2d . 575 (Tex.Civ.App. San Antonio, 1943), reh.den.

There the husband named his father ·as beneficiary of a fraternal life

insurance policy, but the father died, and on the husband's death, his

brother told the wife that he wotild collect the proceeds for her and would

then give her a part of the proceeds.

Then the brother claimed the entire

proceeds under a parol trust, claiming that the husband had told him that

if the brother would pay the premiums, he would receive the benefits.

In holding that no parol trust had been established, the court stated the

rule as earlier stated in Garabrant v. Burns, 111 S.W. 2d 1100 (Comm.

App. Sec. A, 1938), that a beneficiary cannot be changed without

written consent . . Regardless of the intent of the parties, where the

beneficiary has not been changed according to the rules of the policy,

the named beneficiary will get the proceeds.

Here, of course, there was

no named beneficiary since the husband had died, but the wife was the

beneficiary by operation of law.

Olivares v. Olivares, supra, at 576.

The court makes statements which are worth recounting in order to

distinguish them with the later cases:

The beneficiary could not be deprived of the proceeds of the

policy by a so-called trust agreement that she had not

consented to, and of which she never heard until after her

husband's death. There are authorities holding that a trust

such as it contended for her by appellee can be created with the

consent of the beneficiary, but we have found no authority

holding that such a trust can be created without the consent

of the beneficiary.

It would be against public policy to have the law otherwise.

The very salutary rule laid down in Garabrant v. Burns, supra,

would be set at naught. It would be just as difficult for a

beneficiary after the death of the insured to combat a contention

that a trust had been created as to show there had been an oral

change of beneficiary, or a change in some other manner not

authorized by the policy or the constitution and bylaws of the

society.

It would perhaps be best to examine the reasoning of this case

in terms of the explanation given by the Court in Ballard v. Ballard,

supra.

The court looked at the provisions of the Texas Trust Act,

Article 7425b-7, stating that trusts of real property must be in

writing, and the Court implied from the exclusion of the language that

trusts in personal property did not have to be in writing.

Further, the

court noted that the Restatement of Trusts, sec. 17 says that a trust in

the proceeds of life insurance may be created by a parol direction of

insured to the beneficiary to hold them in trust where the policy

provides for reserved power in the insured to change the beneficiary.

Ballard v. Ballard, supra, at

8l6-17~

Section 57 says that such a

disposition of insurance proceeds is not testamentary since a present

trust is created, the beneficiary taking his rights as such in trust,

and this independently of an express designation in the policy of the

beneficiary as trustee

Trusts, S 57.

Ballard v. Ballard, supra, at 817; Res. 2d.

The Court goes on to say that these principles have

been restated by the courts in Eaton v. Husted, supra, and Dunn v.

Second Nat'l Bank of Houston, 113 S.W. 2d 165 -(Comm. App. Sec. B.,1938),

but the court

f~lt

that these authorities were all distinguishable from

Garabrant and Olivares in that the former dealt with equitable principles

while the latter two cases dealt with strictly legal principles.

(Ballard v. Ballard, supra, at 817.).

The Ballard court, in

re~evaluating

the Olivares decision,

determined that the court had merely found an invalid executory contract

and did not think that it was faced with a trust situation at all.

However, the sticky problem in Olivares is the court's

relating to the beneficiary.

The court said as quoted

d~scussion

that the

beneficiary had to consent to any trust arrangement with the insured or

-22-

else the trust creation would be invalid.

If this were the rule of

law to be applied in every case, many of the persons intended to be

benefited by the parol trusts already mentioned would probably have lost.

This rule would require that the insured and the beneficiary have a

written understanding and probably to be safe that the trust arrangement

be clearly set out in the life insurance policy itself.

Otherwise, most

of the "trustees" previously discussed would have gotten all the proceeds

for themselves as most of them were collateral relatives of the insured

wh.o preferred to try to recover the proceeds for themsel ves without using

any of it for the insured's wife or children intended to receive the

money.

This ought to serve as one reason among several that an insured

should select a trustee who will not be overtaken by selfish motives such

as a wife or husband.

If the nearest relative of this type is not

available, it would probably be the wisest choice to select a corporate

trustee or at least the insurance company in order to avoid the family

squabbles that inevitably seem to arise.

of situations

.'

ar~

Where the trusts in these types

being proven by parol for the most part, a person who

.

wants to claim as beneficiary would only have to deny any agreement with

the settltir, and a court would be powerless to make any other disposition

since the beneficiary would have had to consent.

The more obvious rule is the one that the courts have adopted.

The Ballard court discusses this, saying that the rule stated in

Olivares was merely dicta since the court found no real trust issue and

that it is contrary to the law as stated by the Texas Supreme Court in

Dunn v. Second Nat'l Bank of Houston, supra.

Ballard v. Ballard, supra,

at 817.

There is one problem that the courts dealing with life insurance

-23-

trusts have never referred to, probably because of the state of the law

at that time, and this is the problem involving fraud on the wife's rights.

Prior to the enactment of the Family Code giving the wife an equal power

of management over the community estate, the husband was considered the

sole manager of the community property of the parties.

While the wife was

considered to be a one-half owner, disposition and management was left

solely to the husband.

Apparently since the law was as it was, the court

in Olivares did not find that there was any fraud,even though the policy

was initially bought with community funds and the wife never knew of the

policy or consented to giving the proceeds to a third party.

It is quite

possible that if the same case were to come before the court today. the

court would be able to find that the husband had defrauded the wife.

Notwithstanding , the fact that the husband's brother paid part of the

premiums, the fact that the wife did not know of the arrangement and the

fact that the policy was intended to be payable to another would be a

certain basis for fraud upon the rights of the wife, and in addition.

---.

the court would also be likely to find that a trust was created

si~ce

the

Olivares holding seems contrary to the bulk of Texas law on the subject.

Another pre-Family Code case presented a situation which also

might be different if decided now .. Volunteer State Life Ins. Co. v.

Hardin. 197 S.W. 2d 105

(Tex. 1946).

There the son was claiming that

he was entitled to share in the proceeds of a life insurance policy

taken out by his father and made payable to a party not his wife.

Plaintiff's father had taken out two policies. one in favor of his estate

and another payable to his parents. and both policies were taken out

during his marriage to plaintiff's mother.

-24-

The father retained the

rights to change the beneficiaries and exercise all the rights under the

policy without the consent of any beneficiary.

Then the father changed

the beneficiary to his wife with the plaintiff as the secondary

beneficiary, and the wife died intestate thereafter with the .plaintiff as

her only heir.

After this occurred, the father changed the beneficiary

again to his two sisters, and at his death, plaintiff claimed a right in

one-half the proceeds to the extent of one-half the surrender value as of

the date of the mother's death.

supra, at 106.

Volunteer State Life Ins. Co. v.

Hardi~;

The trial court determined he had no such rights in the

policy, but the Court of Civil Appeals reversed and gave him the desired

one-half.

On appeal to the Supreme Court, the case was again reversed,

holding that the plaintiff had no rights in the proceeds.

The rationale

of the court was that there had been no intent

to defraud the wife of her rights, and thus, the proceeds of the policy

coul d vest in the named benefi ci ary even though purchased duri ng marri age

presumably with community funds.

supra, at 106.

Th~

Volunteer State Life Ins. Co. v. Hardin,

court further goes on to say:

.. . the proceeds of the policy belong to the person named as

payee, and it becomes property upon the contingency of the death

of the insured in the lifetime of the payee. .Therefore, as it

could not become the property of the husband or the wife during

the lifetime of both of them, it cannot be held to be community

property, and is therefore the separate property of the one to

whom it is made payable. Volunteer State Life Ins. Co. v. Hardin,

supra, at 107.

The contingency of life insurance proceeds has been well accepted,

and the court explains its reasoning by saying that where the insured has

retained the right to change the beneficiary, the named beneficiary

obtains no enforceable · rights in the policy's proceeds until the death of

the insured.

Because the insured has such a right, the named beneficiary

~5-

may properly be divested of this contingent right which cannot vest until

the death of the insured.

probably correct.

Therefore, this part of the Hardin case is

As the above quote illustrates, the policy in the case

remained contingent until the husband as insured died, and he had the

right to change the beneficiary as often as he wished until that time so

that by the wife's predeceasing him, she had not obtained any rights in

the proceeds.

However, this should be strictly qualified in light of the

law as it exists today under the Family Code.

The Supreme Court in

Hardin flatly rejected a case plaintiff argued where the defendant had

claimed that the husband couldn't use community property without the

wife's consent, rejecting it on the basis that Article 4619 gave the

husband the right of sole management of all community property.

State Life Ins. Co. v. Hardin, supra, at 106.

Volunteer

The court further decided that

not only could the son not receive half the proceeds but that the

community estate was not entitled to be reimbursed because husband was

entitled to make this contract of insurance through his rights as

community manager.'-<-,It seems quite probable that in a similar situation,

the Supreme Court woul d probably overrul e thi s theory .

In. order to defeat

the wife's possible one-half interest, it would be necessary to prove that

the wife had joined in making a third party the beneficiary of the policy

and overcome the presumption that the husband had given the policy to

another in fraud of the wife's rights.

Re~ardless

of the outcome on this

score, it also seems certain that there would be a right of reimbursement

to the wife's one-half of the community estate.

Thus far, the cases described have for the most part deal·t with

the life insurance trust with the children or spouse intended to benefit

from the trust, but there is no reason why someone other than an immediate

R26-

family member, or what is called the object of the insured's bounty,

cannot be the intended recipient of the proceeds.

distinctions can be drawn from

t~cases

Several interesting

in which creditors were expressly

intended to benefit from a life insurance policy, and an examination of

some of the cases in this area will better serve to illustrate the

distinctions . ..

In a short and straightforward opinion, the Kentucky appellate

court in Crews v. Crews' Administrator, supra, looked at the facts where

the deceased had bought $1,000 ·in life insurance in order to satisfy

the obligation he owed to one particular creditor, and any residue from

the proceeds was to be paid to the wife.

The administrator of his estate

contested the trust on the basis that the funds should be used to satisfy

other creditors because the estate itself was insufficient to pay all

the debts, but the court rejected the administrator's argument, holding

that the intent of the deceased was clear and had been established by

several witnesses that the wife was to receive any balance.

determined that

·th~

The court

disposition was reasonable since the insured had a

wife and several minor children, apparently believing that the insured's

intent was toput his family in as good a financial position as possible

in the event of his death.

Since the court followed the general rule

that a trust in personalty could be created by parol, the trust was

upheld as to the one creditor and the insured's family.

In a California case, Fahr.ney v. Wilson, supra, the deceased had

taken out a life insurance policy and told his wife and creditors on

numerous occasions that it was his intent to protect the business, a

logging-related business, where he had large debts and a small cash

reserve by the nature of his business.

It was the arrangement that if he

died, the wife would pay his creditors and keep any balance.

The wife,

at the husband's death, tried to keep the proceeds without making the

promised payments, and in a suit .brought by a creditor, the lower court

held that the creditor was entitled to his portion of the proceeds .

In

affirming the decisions, the appellate court framed the issue as whether

the statements and conduct of the deceased showed with reasonable

certainty an intent to create a trust and whether the subject, purpose,

and beneficiary of the trust was sufficiently established as well as

whether the wife accepted a position as trustee.

The court reviewed

the general rules of oral trusts and determined that a trust can be

created regardless of whether the beneficiary is named as trustee in the

policy or whether the insured and beneficiary have an agreement to that

effect outside the policy.

A significant fact the court looked .at .was that

the insured already had a large policy, and it inferred from this that the

policy taken out later was primarily for the benefit of creditors, and

therefore found no problem in awarding those proceeds to the creditors

through the

wife , ~s

trustee.

Fahrney v. Wilson, supra, at 673.

There have been two Texas cases involving creditors as

beneficiaries of insurance proceeds.

In Rape v·. Gardner, supra, a

physician treated the deceased for a terminal illness.

Upon

presentation of a bill for $100, the deceased agreed with the doctor to

pay him the proceeds of a life insurance policy in consideration for

continued medical treatment.

The wife as beneficiary agree.d to the

arrangement but reneged when her husband died.

The court determined that

the wife had breached the trust and said that the creditor was entitled to

receive the proceeds.

Citing the proposition that in :a trust the proceeds

could be established by parol, the court went on to quote from a New York

;-28-

case with approval to the effect that even

tbo~~h~

life insurance policy

is a contingent interest, it becomes vested at the death of the insured,

and the trustee having collected .i t is obligated to carry out the trust

which attaches to those funds.

Hirsh v. Auer, supra, at 398; Rape v.

Gardiner, supra, at 595-97.

Finally, the Supreme Court of Texas in an important case,

Dunn v. Second Nat'l Bank of Houston, supra, faced a more specific issue:

Can the trust in favor of a creditor be shown by parol evidence when the

terms do not specify the particular part of the obligation to be paid,

especially when the entire obligation exceeds the amount of the proceeds?

The court answered that parol evidence had to be resorted to in order to

determine if there was indeed a debt and how much it was, the rationale

being that in order to carry out the insured's intent, it was essential

to look outside the policy itself.

supra, at 170.

Dunn v. Second Nat'l Bank of Houston,

The court says at the outset that in Texas a creditor can

be the beneficiary of a policy but that such creditor is only entitled to

keep the amount' du€ it and will hold the excess as trustee for the estate

of the insured. Dunn v. Second Nat'l Bank of .Houston, supra, at 169.

But

once the court has looked this far outside the written terms of the

instrument, can the court look to see if the insured's aim was to protect

the creditor against particular losses?

In determining that this was

permissible, the court answered that the whole point of designating the

creditor as beneficiary in the first place is to insure against possible

loss, and the insured's intent is only made more certain by the fact that

he has been so specific in designating the purpose of the trust.

The

court, however, qualifies the creditor's right to unrestricted use of the

proceeds by saying that the most likely way that a creditor in this

situation could ever lose the benefit of the trust is through estoppel

or by an innocent purchaser taking the trust res without notice of the

creditor's interest.

However, this did not arise in the case, and the

court did not elaborate on its comments.

Certainly the cases naming creditors as beneficiaries of the

policies do not differ greatly in their facts from those naming family

members as beneficiaries, but there are differences in the way the courts

seem to regard them.

In the first instance, life insurance policies that

have been given to creditors have been given for consideration for debts

or obligations owed to the creditor.

In this respect, it would seem

apparent t~at there is no issue of a gift having been made since a

conveyance made in return for an adequate consideration is more akin to a

bargain rather than an outlay of personal property for which nothing is

expected in return.

There is further no problem involved if the proceeds

exceed the amount owed

t~

the creditor "since, as the Dunn case has

indicated, the creditor is entitled to retain only the amount which will

satisfy the

obli~ation

the insured owed.

This is in sharp contrast to the

majority of cases on life insurance trusts where the person to be

benefited is often a "minor child or wife so that there is at most a moral

obligation or an obligation for support which does not require legal

consideration to be enforceable.

Therefore, it may be easier for a court

to determine the validity of a trust in favor of creditors since the

facts of

con~ideration

make it much closer to being a question of law

not requiring a balance of equities as in the trusts involving family

members.

Another distinction to be drawn from trusts declaring a creditor

as beneficiary is that there is less apt to be a question of fraud upon

the rights of a spouse.

While the cases primarily deal with husbands

who have made life insurance policies payable to a wife, there is no doubt

that in Texas the same rights would apply to either spouse, especially

under the provisions of the Texas Family Code and the recently enacted

equal rights amendment.

Clearly, as already discussed at length, there is

a problem of fraud on the rights of a spouse when the other makes a third

party the beneficiary of a life insurance policy which has been purchased

during marriage with community funds.

A greater number of factors have

to be examined in that situation, resulting in questions of fact that

must be determined by the trier of facts.

The contrary result may be an

almost certainty when a creditor is made the beneficiary of a life

insurance policy.

In any state, the debts owed by the deceased will have

to be satisfied out of his gross estate, and .i n a common law state this

may in some cases severely reduce the estate left to be enjoyed by the

spouse, if any, and other descedants entitled to a part of the estate.

Though it would not work to the same disadvantage in a community property

state such as Texa.s, the decedant IS half of the communi ty debts woul d be

taken from his half of the community estate, and the half of the other

would be left intact for the surviving spouse, though the community half

subject to the debts would likewise be reduced to the detriment of the

takers under intestacy or will.

In either state, by creation of an

intervivos trust, the deceased, during his life has taken assets to

provide a

m~ans

of satisfaction of certain debts by use of proceeds payable

at his death, thereby avoiding the need to take the debts out of property

remaining at death.

A further advantage is that the spouse has provided

a means for relieving a surviving spouse or other family member from

having to pay the debts of the decedent at a time when the financial

resources may be more limited and instead arranging to provide for those

debts at a time when the deceased is able to evaluate his

debt~

and

provide for them before the emergencies arise.

But there is another matter that has come up in several cases

concerning the admissibility of statements made by the deceased to prove

the existence of a parol .trust.

The

n~tural

question that arises is

whether admissibility of such statements is in contravention of the dead

man's statutes in the various states or whether statements are admissible

under the hearsay rules.

Courts which have ruled on this question have

held that the statements are admissible.

An example of this was found·

in the Fahrney case where the defendant was arguing that the statements

made by the decedent were hearsay, but the court held that the statements,

while hearsay, were admissible to show circumstantial evidence of intent

or state of mind at the time the decedent applied for the insurance policy.

A Texas case, Hughes v. Jackson 81

S.W.2rl~

656 (Comm. App. Sec. A,

1935); was primarily concerned with the issue of statements made by the

deceased.

There a policy had been issued to the deceased, payable to the

defendant as trustee with provislon for an alternate trustee to use the

proceeds for the benefit of the children.

The insured retained the right

to change the beneficiary and to assign the policy.

The policy had been

procured at the outset at the defendant's suggestion, and they had

discussed how the proceeds if needed were to be used for education.

The deceased stated to the defendant that the defendant and the alternate

trustee were being listed as trustees on the policy because the insured

knew that her wishes would be carried out.

Before the insured's death,

both trustees paid the premiums, and after the death of the insured, the

-32-

defendant paid the premiums.

company testified

The district manager of the insurance

that insured had made defendant the trustee in return

for a promise to pay the premiums.

By the time of the trial the defendant

had spent a substantial sum for the support and education of one child,

and the other child died, so the survivor and the guardian of a third

child brought suit for one-half the proceeds each.

The trial court gave

a directed verdict to the defendant, but the Court of Civil Appeals

reversed,holding that the evidence as a matter of law showed the creation

of an active trust in the insurance proceeds and that the defendant was

·the trustee with practically unlimited discretion.

The appellate court

also found that when the mother died, each child had become vested with

a one-third beneficial interest in the proceeds, and when one child died,

his two sisters as his heirs took his share free of trust.

The

Commission in a partial reversal determined that the Court of Civil

Appeals' findings as to the trust and trustee could only be true if the

testimony of the defendant and the manager were taken as true as a matter

of fact by

the '~ury,

but the .court refused to do so.

It determined as a

matter of law that because the defendant was an interested party testifying

to conversations with a person then dead that the jury should have weighed

his testimony and passed on his credibility.

658; and Koziell's Trust, supra, at 232.

Hughes v. Jackson, supra, at

As to the manager, the court

determined that because there had been eight years since the original

conversation with the insured had taken place and because the manager

could have been regarded as a party friendly to the defendant that the

jury should also have passed on his credibility.

Therefore, the court

was saying that the statements of these two were admissible, but because

of the nature of their possible interests in the outcome, the court was

-33-

unwilling to accept their testimony without first giving the jury an

opportunity to pass upon credibility and attempting to view the evidence

in a' light favorable to the plaintiff. ' The court went on to give guidance

to the jury and the court on remand, say.ing that if the defendant was

believed by the jury, then this would establish an active trust with

discretion in the trustee to use the funds as he saw fit and said further

that he was entitled to spend the money on the children as a family and

was not required to expend the same amount on each child, the only limit

on his power being that he was only to expend the funds for the children

. to avoid a breach of trust duty.

In Ballard v. Lance, supra, the daughter of the deceased/insured

was allowed to testify to the statements made to her by the insured

which established a trust in all the grandchildren with the two named

grandchildren as beneficiaries/trustees.

The court held that these

statements were admissible because the daughter was not testifying in her

own interest. Even

court looked

at ~~he

though she was directly related to the deceased, the

legal relationship under the alleged trust and found

that the daughter, related also to the beneficiaries, was not a person

who had an interest in the trust res and was therefore entitled to testify

to her knowledge of the insured's intent.

In the Texas case, Ballard v. Ballard, supra, involving the parol

trust between a father and his minor daughter, the issue was raised as

to whether the defendant/brother's statements to his attorney and others

to the effect that he knew he had been made

. to care for the daughter were admissible.

benefici~ry

with instructions

The court looked at textual

authorities which have stated that most courts will admit statements of

this sort on a theory of privity of title between the insured and the

-34-

beneficiary, though it is argued that they should not be admissible

because the beneficiary is not taking from or under the insured, but

the court in Ballard simply dismissed the argument as stretching the

technicalities of privity to a point of unfairness.

The court went on to

review the Clausen decision and stated that a single declaration of an

insured is competent alone to engraft a trust on the proceeds of a life

insurance policy.

· Ballard v. Ballard, supra, at 820.

The court's

reasoning wa:s that equity wil] prevent someone in this trustee's position

from getting a windfall and unjust enrichment because the trustee cannot

question his role and escape his fiduciary duty by invalidating the trust

on the basis of an inadmissible declaration by the insured.

Thus, there appears to be no evidentiary obstacles to the

admission of a statement made by the insured to another person regarding

his intent as to the proceeds of a policy.

On the one hand, if it is

hearsay, it is admissible to show state of mind, and in the wills and

trusts area the courts are always primarily concerned about enforcing the

intent of the -,-testator or trustor.

On the other harid,if it is not

hearsay, there is no admission problem anywai, and the court may be

entitled to examine the legal relationship between the parties in order

to determine if one is testifying in his own interest or is making a

declaration against his own interest.

Therefore, while it is an issue to

be considered, it is not one that has caused severe problems in resolving

the question of whether a trust exists at all.

In any consideration of trust problems, it is essential to look

at the role of the trustee and the applicable standard as well as other

problems such as notice; removal, and enforcement of appropriate remedies.

Without doubt, the general rule is that a trustee is held to a

-35-

high standard of honesty and accountability, and a trustee must be

careful to exercise his duty strictly within the limitations of the trust

terms~

However, depending upon the individual circumstances, courts have

specified the rules more exactly in order to conform with the many

situations in which questions and conflicts can naturally arise.

This

is the importance of court supervision over a trustee at the outset.

First, must a beneficiary always be told that he is being made

beneficiary only to act as trustee for another?

The clear majority of the

jurisdictions have stated that notice to the beneficiary is not necessary

to impose a trust.

In dicta as already mentioned, the Olivares court in

Texas said that it would be impossible to create a trust without knowledge

by the beneficiary that he was not given both legal and equitable title,

but this proposition was overruled later by the Dunn court.

There the court

held that the bank, which did not know 6f the insured's intent to use

the proceeds in a certain way was not required to know or

creation of a para1 trust.

at 171.

Other~ ~ourts

cQn~~nt

to the

Dunn v. Second Nat'l Bank of Houston, supra,

have stated the same principle, and the Massachusetts

court in Cooney went one step further to distinguish the situation where

the settlor makes himself trustee for another, thereby keeping legal

title in himself.

In such a case, the court said it would be necessary

to give notice to the beneficiary of .the trust but that it is unnecessary

in cases where the settlor divests himself of legal title by making '

antoher the trustee.

Cooney v. Montana, supra, at 207.

The

Pennsylvania Supreme Court has also held that notice to the trustee is

not essential, stating that if the trustee does not wish to accept the

obligations placed on him, he has the option at the time he learns of the

trust to refuse to serve before having anything to do with the trust

-36-

res.

Donithen v. Ind. Order of Foresters, supra, at 143-44; and Koziell's

Trust, supra, at 232.

As with the notice issue, the courts in determining what standard

will govern the trustee's actions have had little difficulty.

The

Ballard court in Texas has said that a trustee cannot question his role

as a fiduciary in collecting the insurance proceeds for the intended

recipient, and the court set out the standard that the court must look

at all the evidence in the light most favorable to the plaintiff and

that such evidence must be clear, satisfactory, and convincing before

it is submitted to a jury who is entitled to rest ·upon a mere preponderance

of the evidence.

Ballard v. Ballard, supra, at 820.

Also, in the Cooney

case, supra, the court . determined that the sister had a duty, once the

trust had been established, to show that she had executed the trusteeship

thus far with reasonable skill, prudence, and judgment, including a duty

to keep accurate records.

It will be recalled that this was the case

where the policy produced twice the amount expected because of the double

indemnity provi si.~Jn and the sis ter had only set as i de the amount her

brother had anticipated.

The court said that its duty was to look at

all the circumstances, the existing relations, and feelings between the

parties and that in Massachusetts the standard was that a trustee is held

to accountability not only for the capital but for the income as well.

Cooney v. Montana, supra, at 208-09.

In one of the few cases not finding a trust, the Second Circuit

in Cullen v. Chappell, supra, determined that the defendant had not done

enough to constitute herself as a trustee and said that she had acted