Political Structures NQ Support Material Politics Intermediate 2

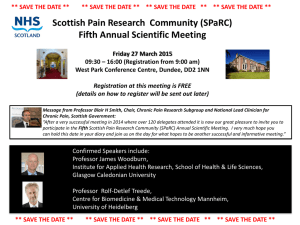

advertisement