12:00 Buddhism 14

advertisement

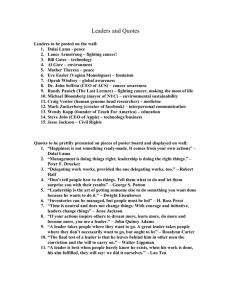

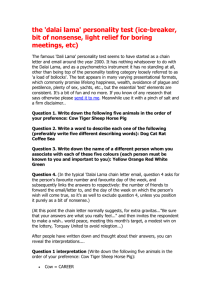

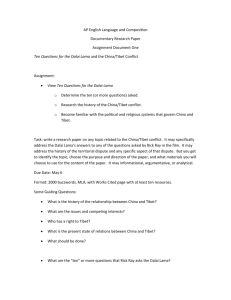

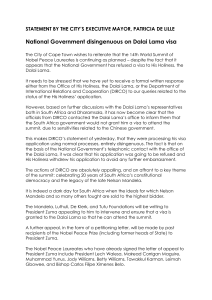

Buddhism 14th Dalai Lama (1935 - ) 12:00 th 14 Dalai Lama Background information The geography of Tibet The Tibetan plateau or Tibetan province is rightly called the roof of the world. The average elevation of the plateau is 4,900 metres (over three times the height of Ben Nevis). Chomolungma (Mount Everest) and many of the world’s highest mountains lie within Tibet. The area is also known as the ‘water tower of Asia’ or the ‘third pole’ as many of the continent’s rivers, including the Ganges, Yangtze, Indus and Brahmaputra, originate from Tibet. The area of the Tibet is 1.2 million kilometres squared (Scotland 78,772 km squared). Despite such size, according to the 2000 Chinese census, the population is 2.62 million (less than half the population of Scotland). Tibetan history Tibet has had a turbulent history. At times the empire of Tibet encroached into what we now call China, and at others it has been subject to the powerful empires of Mongolia and China. Tibet has been at the frontiers of various empires throughout history including Chinese, British, Russian and Sikh. The predominant cultural and religious influence on Tibet is Buddhism, which arrived in the 7th century CE. Tibetan Buddhism regards the aim of life to be the attainment of enlightenment (becoming a ‘Buddha’) for the sake of all beings. Tibetan Buddhists believe that certain spiritually advanced people can help others to achieve this. These ‘saints’ are called bodhisattvas and the dalai lamas have been regarded as examples of such sainthood. These are people who have chosen to be reborn in order to help other beings. In Tibetan Buddhism great emphasis is placed on the importance of the spiritual teacher and his lineage. These lines of teaching have given rise to various monastic traditions in Tibet. The Dalai Lama is head of Gelug branch of Tibetan Buddhism. Another notable head of a particular lineage is the Karmappa (pictured with the Dalai Lama below) who is head of the Kagye tradition. As with other religions in other countries, when Buddhism arrived in Tibet it adapted to the local cultural and geographic conditions. The pre-existing Bon religions, which placed great emphasis on shamanism and imagery still exists within Tibet, but also influenced Tibetan Buddhism. This perhaps explains aspects of Tibetan Buddhism which place great emphasis on visualisation, imagery and ornamentation. A further important aspect of Tibetan Buddhism is an emphasis on scepticism, good reasoning and criticality. Debate is encouraged as a means by which to improve understanding and question tradition. The history of Tibet is contested and varies depending on your perspective. Tibet has been isolated from much of the rest of the world. This isolation has been partly due to its geographical inaccessibility but also has been self-imposed. As the Dalia Lama puts it… “We Tibetans had chosen – mistakenly, in my view, to remain quite isolated behind the high mountain ranges which separate our country from the rest of the world”. (source: The Dalai Lama (1999) Ethics for the New Millenium, Riverhead Books) At various times Tibetan leaders have effectively closed the borders to outside influence. The effects of this have been to create, in many western minds, a sense of mystery around Tibet. This can be seen in the myth of Shrangi-La, the idea of a Himalayan paradise or utopia. To the western mind, the mountains of Tibet represent a challenge to be conquered. In 1924 a British climber, Edward Mallory, when asked why he wanted to conquer Everest, allegedly responded “because it’s there”. Mallory and his climbing partner Sandy Irvine perished on their last pitch towards the summit. Whether they died on the way up or during the descent remains one of climbing’s great mysteries and adds to the mystique of the Himalayas and Tibet. Throughout history Tibet has been the battleground for various empires. For example, in the early 20th century Britain invaded as a response to Russian ambitions in the region. The most recent episode in this history is the claim to rule Tibet by the Chinese government. In 1950 China placed thousands of troops in Tibet to reinforce its claim on the region. In 1959, after an uprising by Tibetans failed, the Dalai Lama fled to India and was allowed by the Indian government to establish a Tibetan government in exile in northern India in Dharamsala. During the 1960’s and 1970’s the atheistic, communist, Chinese regime destroyed most of Tibet’s monasteries and reports suggest that thousands of Tibetans were killed during this time as the Chinese imposed military rule. The Dalai Lama claims 1.2 million Tibetans died. The Chinese government disputes such a claim. To this day it is hard to get accurate information about what is happening in Tibet as the Chinese place strict restrictions on reporting and access to the area. In China itself the authorities censor many web sites. Google web searches are heavily filtered and social networking sites such as Facebook are banned. Some refer to this censorship as the ‘Great firewall of China’. Many human rights groups claim that Chinese authorities have brutally cracked down on peaceful protests and continue to detain and torture innocent Tibetans. However, the Chinese government claims that Chinese intervention in Tibet has been positive and led to the development of improved sanitation, healthcare, education and industry within the area. The Chinese government claim that Tibet was a feudal society governed by unelected religious leaders and that the majority of people were serfs (effectively slaves). China has also encouraged a policy of settlement by nonTibetans in the area. For some this represents a further attempt to dilute or destroy Tibetan identity. Tibet therefore remains in the spotlight as a focus point for discussion of human rights. Indeed the Dalai Lama is often used as a symbol of this and western leaders often arrange meetings with the Dalai Lama as a means to table concerns about human rights abuses in China. At the present time, where China is emerging as an economic superpower; there can be tensions between governments and organisations who want to trade with China, and individuals who wish to change the human rights situation in China. This can be seen in incidents where authorities have declined to meet the Dalai Lama for fear of endangering relations with China or where certain institutions in the west have played down their meeting, or refused to meet, with the Dalai Lama in order to get Chinese business. The importance of Tibet may also take on greater significance given its importance to water supplies in the most populous part of our planet. If climate change predictions are correct this will be a more acute reason for focus on this disputed part of Asia in the years to come. Scottish Buddhism? In Scotland today there is evidence of the growing appeal of Buddhism. Professor Steve Bruce from the University of Aberdeen describes Scotland as a country which is ‘Buddhist by default’. He thinks many people have turned away from the traditional religion of Scotland (Christianity). Perhaps people are attracted to what they see as a religion which has no God, and which embodies the idea of happiness for all that can be found within ourselves rather than in possessions or external authorities. Indeed, many Scots prefer to see Buddhism as a philosophy rather than a religion. The Dalai Lama has embodied much of these qualities. When he comes to Scotland, his talks and events are sold out, and his books sell thousands of copies. In Scottish schools the majority of pupils studying RMPS at Higher will study Buddhism (though in most cases this will be chosen for them by their teacher). Scotland is also home to the largest Tibetan monastery in Europe. Kagye Samye Ling was founded in the 1960’s and can be found northwest of Lockerbie in Dumfriesshire. Every year thousands of visitors (many of them pupils from Scottish schools) travel to Samye Ling in order to learn about Buddhism. The popularity of Buddhism can also be seen more obviously in Scotland today. In a number of interior design or fashion shops, or garden centres one doesn’t have to look hard to find a Buddha. Perhaps people are attracted to the meditative qualities of such images. This may also be the result of the fact that research into meditation or mindfulness is showing that these activities can have major benefits. For example mindfulness meditation is now recognised by the NHS as a form of treatment for depression. Research has also shown benefits in schools, where mindfulness has been used for children with attention deficit disorders or poor self-control. Questions for reflection: 1. This short history has also shown that there are different views of Tibetan history. Have a look at the following websites. One is the Amnesty International site which is campaigning for improved human rights in China and Tibet. The other is the Chinese government’s account of how it has improved the situation in Tibet. Note any differences between them. Which do you think, if any, has the right view? Amnesty International news item on Tibet Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Switzerland: Tibet – From Isolation to Openness 2. Why do you think Buddhism has an appeal for many in the West and in Scotland? 3. Can you think of shops and places where you have seen Buddhist images? A short biography of the 14th Dalai Lama In Tibetan Buddhism it is believed that the Dalai Lama is a reincarnation of a saint called Avalokiteśvara who, they believe is the saint of compassion. Since the 14 th century there have been fourteen such reincarnations. At certain times in Tibetan history the Dalai Lamas have been involved in the political governance of Tibet as well as in spiritual leadership. In 1578, the Mongolian ruler, Altan Khan gave the title Dalai Lama to Sonam Gyatso. The Mongolian title means "the wonderful Vajradhara, good splendid meritorious ocean". Usually however, the term Dalai Lama is taken to mean ‘ocean of wisdom’. Another title also used for the Dalai Lama is ‘Kundun’ which means ‘presence of the Buddha’. The current Dalai Lama is the fourteenth in an unbroken line. Upon the death of the 13th Dalai Lama in 1933 Tibetan religious leaders sought guidance about where his successor would be re-incarnated. They used signs and visions in order to establish the location, eventually believing that the 14 th Dalai Lama would be re-incarnated. They had a number of possible contenders in mind from different regions in Tibet. Delegations of monks were sent out to identify possible candidates. A group of monks were sent to the village of Takster where they found a 2 year old child named Lhamo Thondrup. After a series of tests involving possessions of the deceased Dalai Lama, the child was deemed to have passed, scoring higher than the other children tested. He was declared the 14th Dalai Lama. In the following account of how the Dalai Lama was found a group of high ranking monks (lamas) have travelled to the small village. On entering the house of Lhamo Thondrup they are struck by how friendly and familiar the two year old was with one of the lamas, seeming to know their names: “The lama was disguised in a cloak lined with lambskin, but around his neck he was wearing a rosary (prayer beads) which had belonged to the 13th Dalai Lama. The little boy seemed to recognise the rosary, and he asked to be given it. The lama promised to give it to him if he could guess who he was, and the boy replied that he was Sera-aga, which meant in the local dialect, ‘a lama of Sera’. The lama asked who the ‘master’ was and the boy gave the name of Lobsang. He also knew the name of the real servant, which was Amdo Kelsang”. (source: Dalai Lama (1962) My Land and My People: Memoirs of the Dalai Lama of Tibet, Lhasa: Potala, cited in Craig, M. () Kundun, London: Harper Collins, p15) Other tests for the child involved presenting him with pairs of possessions. One of each pair was a genuine possession of the 13th Dalai Lama: Next day, they offered him the late Dalai Lama’s walking stick and Kesang Rinpoche’s. He looked carefully at these and started to take the fake one. The search team thought he was going to make a mistake, but the boy changed his mind, put the wrong one back and took the correct one. Later, when they thought about this near miss, they realised that the duplicate walking stick had in fact also belonged to the Dalai Lama, who had given it to a lama, who had in turn given it to Kesang Rinpoche. So the Takster boy had had made no mistake in the three tests. The last test involved the small damaru drum the 13 th Dalai Lama had used to summon his servants. It was very plain, while the duplicate one was particularly beautiful, with ivory, gold and turquoise and a long, multicoloured brocade tassel. Kheme later said he (the boy) was very nervous about this test. However, the child again chose correctly, taking it immediately in his right hand and beginning to play it”. (source: Goldstein, M. C. (1989) A History of Modern Tibet, the Demise of the Lamaist State, Los Angeles: University of California Press, p319) The boy’s mum recalled that later that night the boy insisted on taking the drum to bed with him. During the process of identifying the Dalai Lama the Tibetans were also wary of Chinese interference and the possibility that the Chinese would appoint their own Dalai Lama as a puppet ruler of Tibet. A telegraph sent by British officials bears this concern out: “FOR FEAR OF CHINESE INTERFERENCE, GREATEST SECRECY IS BEING MAINTAINED AND IT IS POSSIBLE THAT AS A PRECAUTION THE TIBETAN GOVERNMENT MAY ANNOUNCE THE DISCOVERY OF SEVERAL POSSIBLE CANDIDATES”.(source: Oriental and India Office Collections, Political Files and Collections, L/P&S/12/4178 File 15) After passing these tests the boy was taken from his village (his family were allowed to join him) and travelled to Lhasa, the Tibetan capital and site of the Potala Palace, the residence of the Dalai Lama. Shortly after this he was initiated as a Buddhist monk. He would wear the saffron and yellow robes and was given a new name Tenzing Gyatso. At the age of six the boy began an intensive education into all aspects of Tibetan culture, as well as philosophy, Sanskrit and Buddhism. When he was eleven the Dalai Lama met an Austrian Mountaineer Heinrich Harrar. This was perhaps an influential meeting as the young Dalai Lama learned much from Harrar about the world outside Tibet. Indeed, he wrote later: “As a boy, there was a time when I was rather more interested in learning about the mechanics of an old film projector… than in my religious or scholastic studies.” (Mehrotra 2005, p9) Such moments were also written about Harrar and later represented in the movie ‘Seven Years in Tibet’ (starring Brad Pitt) which documented the young Dalai Lama’s friendship with Harrar and interest in western culture and science. In 1950, the Dalai Lama, now aged 15 formally became the political leader of Tibet. Initially the Dalai Lama was attracted to many of the ideas of equality that communism seems to embody and he travelled to China to enter talks with the Chinese leader Chairman Mao. However, Mao’s attitude to religion (he famously declared that religion is ‘poison’), his ambitions for Tibet, and growing unrest were to force the Dalai Lama to escape from his own country in 1959. The Dalai Lama has been living in Dharamsala, northern India, to this day. In Dharamsala, the Dalai Lama sought to create a government in exile, as well as offer a sanctuary for Tibetan refugees and a community dedicated to preserving Tibetan cultural identity. In the years since 1959 he has campaigned for Tibetan autonomy and cultural identity. He has persistently sought to peacefully bring about recognition of Tibetan identity and the creation of a democratic constitution for his country. Latterly he has put forward the idea of devolution for Tibet and, on one of his visits to Scotland, he was much interested in the way Scotland has a devolved parliament, yet remains within the United Kingdom. The Dalai Lama’s latest proposals to the Chinese government are that Tibet remains a devolved province of China, but enjoys a degree of cultural independence. In 1989 the Dalai Lama was presented with the Nobel Peace Prize. Since his exile from Tibet he has travelled to more than 62 countries. He has met with presidents, prime ministers and crowned rulers of major nations. He has also held dialogues with the heads of different religions and many well-known scientists. Apart from his role in administrating affairs in Dharmasala and taking his teachings around the world the Dalai Lama has authored over 70 books about a range of topics including introductions to Buddhism and meditation, religion and science and inter-faith dialogue. In 2008 he announced that he was stepping aside from his role as leader of the Tibetan government in exile. However, he continues to travel and to write, and is visiting Scotland in 2012. Alarmingly for some of his followers he has also declared that there may not be a 15th Dalai Lama upon his death. “I have not much worry about it. If the Tibetan people feel it necessary to choose another Dalai Lama, all right, then they will choose a Dalai Lama. If people feel it not necessary, not much better to do so, then no Dalai Lama will exist”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p80) Questions for reflection 1. According to Tibetan Buddhists the Dalai Lama was identified as the fourteenth man to hold the title in an unbroken line of rebirths. The boy Lhamo Thondrup passed a series of tests whereby he recognised the belongings of the 13th Dalai Lama. Do you think this is possible? 2. The current Dalai Lama has hinted that he may be the last in the line. According to him the Karma he generates in his lifetime may not lead to the rebirth of a 15th Dalai Lama. How do you think Tibetans may feel about this possibility? Key Buddhist beliefs of the 14th Dalai Lama Although the Dalai Lama is a Buddhist and arguably the most famous Buddhist among the 400 million people (approximately) who describe themselves as Buddhist, he does not see it as his role to spread Buddhism. That is, he has always remained respectful to the views (religious of otherwise) of people throughout the world without seeking to be some kind of Buddhist missionary. However, he does acknowledge that there is an appetite for Buddhism, particularly in the West: “I sometimes feel a little hesitant about giving Buddhist teachings in the West, because I think that it is better and safer for people to stay within their own religious tradition. But out of the millions of people who live in the West, naturally there will be some who find the Buddhist approach more effective or suitable”. (source: Dalai Lama (2002) Illuminating the Path to Enlightenment, Thubten Dhargye Ling) At the heart of Buddhism is an analysis of the human condition which is called the four Noble Truths. These are, simply put, 1. 2. 3. 4. Life contains suffering Suffering occurs because humans fail to accept the impermanence of all things If we accept that all things are impermanence we can lessen suffering The way Buddhism suggests this can be done is by following the Eightfold Path (which, simply put, is eight recommendations about how we can develop a view of life as it really is through meditation; leading to a recognition of the plight of ourselves and others (compassion), which in turn leads to moral action.) Throughout his life the Dalai Lama has placed this Buddhist diagnosis and ‘prescription’ at the heart of his books and teachings. For him the aim of life (not just human life) is happiness or the cessation of suffering: “We hope that through this or that action we can bring about happiness. Everything we do, not only as individuals but also at the level of society, can be seen in terms of this fundamental aspiration.” (source: Dalai Lama (2002) Illuminating the Path to Enlightenment, Thubten Dhargye Ling) The Dalai Lama has famously stated that his religion is happiness, that he is more interested in what can make all sentient beings happy than in temples, churches and intellectual philosophy. He has written that the ending of suffering is more important than religious traditions and dogma, and that in the modern world, where certain belief systems (religious and atheistic) are often locked in unhelpful conflict, there is a pressing need for a universal morality that goes ‘beyond religion’; a secular (nonreligious) approach to life that is universally agreed. It may seem strange for the world’s most famous Buddhist to be saying that religion may be part of the problem and, to a certain extent, should be abandoned. However, the Dalai Lama is perhaps being remarkably consistent to the Buddhist principle of avoiding attachment to ‘non-enduring’ things, even when the ‘things’ happens to be religions themselves. Perhaps this apparent contradiction only arises if we see religion as a set of fixed, absolute answers to the ultimate questions (something the Dalai Lama and many Buddhists do not believe). The Dalai Lama thinks however, that although all beings wish to be happy, that they often seek happiness in the wrong place or in the wrong things. Happiness, for him, cannot be found in material possessions or in anything outside of ourselves. He has noted that levels of anxiety and depression seem to be higher in more wealthy and technologically developed countries than in other parts of the world. This is borne out by World Health Organisation evidence that show that not only is depression becoming more common in Europe, but that it is happening earlier in people’s lives. For the Dalai Lama the failure to understand the changing nature of reality leads to grasping, and grasping leads to many forms of suffering: “According to Buddhist psychology, most of our troubles are due to our passionate desire for and attachment to things that we misapprehend as enduring entities. The pursuit of the objects of our desire and attachment involves the use of aggression and competitiveness as supposedly efficacious instruments. These mental processes easily translate into actions, breeding belligerence as an obvious effect. Such processes have been going on in the human mind since time immemorial, but their execution has become more effective under modern conditions. What can we do to control and regulate these “poisons” – delusion, greed and aggression? For it is these poisons that are behind almost every trouble in the world". (Source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p14) All of the Dalai Lama’s views can be traced back to the Buddhist principle of impermanence and the failure of humans to grasp this. Another view on the nature of impermanence is the idea that everything is connected; that nothing is free from the influence of other phenomena. This perhaps explains the Dalai Lama’s interest in science which, after all, is a subject which examines and seeks to explain the nature of impermanence and interdependence. For him the study of science has enriched and supported his Buddhism: “The insights of science have enriched many aspects of my own Buddhist world view. Einstein’s theory of relativity, with its vivid thought experiments, has given an empirically tested texture to my grasp of Nagajuna’s theory of the relativity of time. The extraordinarily detailed picture of the behaviour of subatomic particles at the minutest levels imaginable brings home the Buddha’s teaching on the dynamically transient nature of all things. The discovery of the human genome all of us share throws into sharp relief the Buddhist view of the fundamental equality of all human beings”. (source: Dalai Lama (2005) The Universe in a Single Atom, London: Little Brown, pp217-8) As for himself, like the Buddha, the Dalai Lama is keen that other people do not worship him or promote him as some infallible source of wisdom: “Unfortunately, many have unrealistic expectations, believing that I have healing powers or that I can give some sort of blessing. But I am only an ordinary human being. The best I can do is try to help them by sharing in their suffering.” (source: Dalai Lama (1999) Ethics for the New Millennium, Riverhead Books, cited in Mehrota, R. (ed.) (2006) The Essential Dalai Lama, London: Hodder Mobius, p5) “I always believe that we human beings are all essentially the same – mentally, emotionally and physically. I want to make clear, however – perhaps even warn you – that you should not expect too much. There are no miracles. I am very sceptical of such things. It is very dangerous if people come to my talks believing that the Dalai Lama has some kind of healing power to heal. Some time ago, at a large gathering in England, I said the same thing. At that time I told the audience that if there is a real healer out there, I want to show that person my skin problems!” (source: Dalai Lama (1999) Illuminating the Path to Enlightenment, Thubten Dhargye, cited in Mehrota, R. (ed.) (2006) The Essential Dalai Lama, London: Hodder Mobius, p5) He also humbly invites people to read and learn from his teachings in so far as they are useful, concluding one of his books with these words: “Now if these words are helpful for you, then put them into practice. But if they aren’t helpful, then there’s no need for them”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p86) Questions for reflection 1. What do you think of the Buddhist ‘diagnosis’ of what it is to be human? 2. Buddhism has been said to be more a philosophy than a religion as it has no belief in God and is more concerned with stopping suffering than finding out the ultimate answers of existence. 3. Do you think this may be why Buddhism seems to appeal to so many people in the ‘West’? 4. Do you agree with the Dalai Lama that we tend to give “too much attention to the external, material aspects of life while neglecting moral ethics and inner values”? 5. Can you give examples of where this might be the case? 6. What do you think of the Dalai’s belief that morality does not need to depend on religion and that humanity needs to go ‘beyond religion’ in order to live in peace? 7. The Dalai Lama believes we suffer because we compete aggressively for things which do not last. 8. Can you think of how this may manifest itself? 9. What do you think he means when he says “Such processes have been going on in the human mind since time immemorial, but their execution has become more effective under modern conditions”? 10. Why do you think depression is happening at an earlier age and more commonly in developed countries? The 14th Dalai Lama and specific moral and political issues This section includes reference to his views, some of them changing on issues such as war, materialism, crime and punishment, and the question of Tibet. The Dalai Lama’s response to controversial issues is that people must be able to make up their own minds. The Dalai Lama on war and peace and the Tibet question Since his escape from Tibet in 1959 the Dalai Lama has been campaigning for Tibetan independence and cultural preservation. He has sent plans for Tibet to China and offered to meet with Chinese leaders in order to discuss the issue. These plans and requests have consistently been ignored. Despite this the Dalai Lama says he feels no anger or need for revenge against the China. He thinks that these things will only make the problem worse. He has said he includes the Chinese in his meditations on compassion and that though they have taken his country, he refuses to let them take his peace of mind. Throughout this time he has been a passionate advocate for non-violent means to achieve freedom for his people. In doing so he is following his Buddhist principles which centre on the alleviation of suffering and recognise that much suffering is caused and continued by greed for possessions, resources and territory. His Buddhism suggests that to use violence in an attempt to end violence is always counter-productive and leads to more suffering. He described these views in his 1989 Nobel Prize for Peace acceptance speech: “I am very happy to be with you here today to receive the Nobel Prize for Peace. I feel honoured, humbled, and deeply moved that you should give this important prize to a simple monk from Tibet. I am no one special. But I believe the prize is recognition of the true value of altruism, love, compassion, and nonviolence which I try to practice, in accordance with the teachings of the Buddha and the sages of India and Tibet… …I accept it as a tribute to the man who founded the modern tradition of nonviolent action for change – Mahatma Gandhi – whose life taught and inspired me. And, of course, I accept it on behalf of the six million Tibetan people, my brave countrymen and women inside Tibet, who have suffered and continue to suffer so much. They confront a calculated and systematic strategy aimed at the destruction of their national and cultural identities… …The suffering of our people during the past forty years of occupation is well documented. Ours has been a long struggle. We know our cause is just. Because violence can only breed more violence and suffering, our struggle must remain non-violent and free of hatred. We are trying to end the suffering of our people, not to inflict suffering upon others”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, ppviii-ix) Other views of the Dalai Lama on war, violence and Tibet: “It is the enemy who can truly teach us to practice the virtues of compassion and tolerance” (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p6) “In olden times when there was a war, it was a human to human confrontation. The victor in battle would directly see the blood and suffering of the defeated enemy. Nowadays, it is much more terrifying because a man in an office can press a button and kill millions of people and never see the human tragedy he has created. The mechanisation of war, the mechanisation of human conflict, poses an increasing threat to peace”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p6) “By far the greatest danger facing humankind – in fact, all living things on this planet – is he threat of nuclear destruction… I would like to appeal to all the leaders of the nuclear powers who literally hold the future of the world in their hands, to the scientists and technicians who continue to create these awesome weapons of destruction, and to all the people at large who are in a position to influence their leaders: I appeal to them to exercise their sanity and begin to work at dismantling and destroying all nuclear weapons”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p7) “Anger, hatred, jealousy – it is not possible to find peace with them. Through compassion, through love, we can solve many problems, we can have genuine happiness, real disarmament. One of the most important things is compassion. We cannot but it in one of New York City’s big shops. We cannot produce it by machine. But by inner development, yes. Without inner peace, it is impossible to have world peace”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p15) “In order to live together on this planet we need kindness, we need a kind atmosphere rather than an angry atmosphere”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p27) “if we use violence in order to reduce disagreements and conflict, then we must experience violence every day and I think the result of this is terrible. Furthermore, it is actually impossible to eliminate disagreements through violence. Violence only brings even more resentment and dissatisfaction. Nonviolence, on the other hand, means dialogue, it means using language to communicate. And dialogue means compromise, listening to others’ views and respecting each others’ rights in a spirit of reconciliation. Nobody will be 100% winner, and nobody will be 100% loser. That is the practical way. In fact, that is the only way. The reality of the world today means that we need to learn to think in this way. This is the basis of my own approach – the ‘middle way’ approach. Tibetans will not be able to gain 100% victory for, whether we like it or not, the future of Tibet very much depends on China…The principle of non-violence should be practised everywhere. This cannot be achieved simply by sitting here and praying. It means work and effort, and yet more effort”. (source: Dalai Lama (1999 The Heart of the Buddha’s Path, cited in Mehrota, R. (ed.) (2006) The Essential Dalai Lama, London: Hodder Mobius,pp24-25). Questions for reflection 1. Do you agree that violence cannot resolve disputes? 2. Are there situations where ‘dialogue’ is impossible and violent action is necessary? 3. Do you think the Dalai Lama’s strategy is working with regards to achieving freedom for Tibet? The Dalai Lama on the environment Buddhism is a world view that is predisposed to a deep respect for the natural world. This is the case for two reasons. 1. The idea of the interdependence of all things is right at the heart of the Buddhist world view. Therefore everything is connected and related to everything else. The natural world therefore sustains all beings and should be respected and protected, and 2. Buddhism suggests that all beings (not just humans) are trying to end suffering or be happy. On this view humans are not given special importance (as perhaps they are in the three major Middle Eastern religions). Buddhism seeks, therefore to end suffering for all beings, not just humans. These Buddhist principles are reflected in the views of the Dalai Lama “No one knows what will happen in a few decades or a few centuries, what adverse effect, for example, deforestation may have on the weather, the soil, the rain. We are having problems because people are concentrating on their selfish interests, on making money, and are not thinking about their community as a whole. They are not thinking of the earth and the long-term effects on man as a whole. If we of the present generation do not think about them now, the future generation might not be able to cope with them”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p9) Questions for reflection 1. Do you agree with the Buddhist view that human life is not any more valuable than other forms of life? 2. Despite what we know about the impact of humanity on the environment and the extent to which all life is interconnected, do you think we are learning and acting to change things? Is this happening fast enough? The Dalai Lama on materialism and economics As you would expect from the above summary of Buddhism, Buddhists do not think happiness can be based on material success. The Dalai Lama has repeatedly suggested that all humanity must begin to look to build a way of life on inner values and mutual respect rather than the relentless collection of material goods. The Dalai Lama has noticed that it is often the case that less technologically advanced, less materially developed societies, tend to suffer from less anxiety and depression. He has stated that one of the reasons for this may be due to technological success, which makes people less dependant on each other. That is, in rural, undeveloped societies, there is a stronger social bond or sense of community than you may find in societies where people live very much as individuals, often connected only by digital technology. The Dalai Lama has also noted with interest recent research which suggests that happiness in societies has nothing to do with the wealth of the society, but rather with the levels of equality within the society. In a country like Scotland, which is among the wealthier nations, there is a massive gulf between the richest and poorest. The evidence suggests that countries which have not so much wealth, but where it is more equally distributed, are happier. Here are some quotes from the Dalai Lama on these issues: “In the sphere of international relations… a sense of greater or shared responsibility is particularly needed. Today, when the world is becoming increasingly interdependent, the dangers of irresponsible behaviour have dramatically increased. In ancient times, problems were mostly family-sized and were solved at the family level. Unless we realise that now we are part of one big human family, we cannot hope to bring about peace and happiness. One nation’s problems can no longer be solved by itself because so much depends on the co-operation of other states. Therefore, it is not only morally wrong, but pragmatically unwise, for either individuals or nations to pursue their own happiness oblivious to the aspirations of those who surround them. The wise course should clearly be based on seeking a compromise out of mutual self-interest”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p60) “Material facilities, material encounters are very necessary for human society, a country, a nation…. At the same time, material progress and prosperity in themselves cannot produce inner peace: inner peace should come from within.” “The most difficult problems in the world, which, in large part, emanate from the most developed societies, stem from an overemphasis on the rewards of material progress… I have heard many great complaints about material progress from Westerners, yet, paradoxically, this progress has been the pride of the Western world… Although material knowledge has contributed enormously to human welfare, it is not capable of creating lasting happiness. In the United States, where technological development is perhaps more advance than in any other Western country, there is still a great deal of mental suffering”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, pp37-8) “A variety of political systems and ideologies is desirable to enrich the human community, so long as all people are free to evolve their own political and socioeconomic system, based on self-determination. If people in poor countries are the denied the happiness they desire and deserve, they will naturally be dissatisfied and pose problems for the rich. If unwanted social, political and cultural forms continue to be imposed by one nation on another, the attainment of world peace is doubtful”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p37) “If you become very rich, even become a millionaire or a billionaire, on the day of your death, no matter how much money you have in the bank, there isn’t any little piece of it that you can take with you. The death of a rich person and the death of a wild animal, each is just the same”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p57) “In today’s materialistic world in which inner values are often neglected, it is very easy to fall into the habit if constantly seeking sensory stimulation. Often I notice that if people are not listening to music, watching television, talking on the phone and so on, they feel bored or restless and don’t know what to do. This suggests that their sense of well-being is heavily dependent on the sensory level of satisfaction”. (Source: Dalai Lama (2011) Beyond Religion: Ethics for a Whole World, London: Rider, p38) “Some time ago, a very wealthy Indian couple from Mumbai came to see me. They asked for my blessings. I told them, as I tell so many others, that the only real blessings will come from themselves. To find blessings in their lives, I suggested that they should use their wealth to benefit the poor. After all, Mumbai has many slums where even basic necessities such as clean water are hard to come by. So, I told them, having made you money as capitalists, you should spend it as socialists!” (Source: Dalai Lama (2011) Beyond Religion: Ethics for a Whole World, London: Rider, p92) Questions for reflection 1. Do you agree with the Dalai’s view that sensory, material satisfaction is not enough? 2. Do you think that, as a society, we are addicted to ‘sensory’ pleasures (give evidence for your answer)? 3. Where can we see, in the political situation in the world today, resource inequality? What are the consequence of such inequality? The Dalai Lama and science This section looks at the Dalai Lama’s interest in science and his public support for dialogue with science. This includes studies he has supported and his writings relating to the nature of consciousness, genetics, cosmology, quantum physics and the alleged benefits of meditation. Buddhism, unlike certain other forms of religion, co-exists better with science. This can be seen in two areas of science in particular: 1. The Origins of the Universe, and 2. The Theory of Evolution Like most Buddhists, the Dalai Lama does not believe in a creator God. Buddhism is a world view concerned with the alleviation of suffering rather than establishing if such a God exists. In this, the Dalai Lama is consistent with the Buddha, who stated that worrying about unanswerable questions such as the existence of God or life after death is a bit like being a man who has been shot in the eye with an arrow asking what wood the arrow is made of rather than healing himself. In other words, for Buddhists it is better to deal with the obvious suffering in life before even beginning to think about the ultimate meaning of it all. Because of these views, Buddhism has no problem with any scientific theories of origin (the current being the Big Bang). As far as the theory of evolution goes Buddhism (and the Dalai Lama) again have no problem with this. In fact evolution, which suggests a process by which all life is connected, sits neatly alongside Buddhist ideas such as the interdependence of life and Buddhist respect for all animals. The Buddhist idea of Karma can also be seen as the idea of cause and effect, which is, after all, the process that the scientific enterprise seeks to uncover. Throughout his life the Dalai Lama has been interested in science and has written on the interface between science and Buddhism. He regards both science and Buddhism as objective attempts to understand reality. He has written on genetics and is particularly interested in current scientific theories about the nature of what consciousness is. He is also interested in what the theory of evolution suggests about the origins and importance of feelings such as compassion and love. He thinks that evolutionary theory is beginning to justify his claims that happiness can only be achieved by compassion for ourselves and others. Similarly he thinks genetic science has demonstrated that we share a common, interconnected humanity. He is also concerned about how some people think science is some infallible process that can answer all questions. He has spoke about the dangers of fundamentalism of all kinds, religious and scientific. The following quotes capture some of his views on science: “We are going into deep outer space based on developments of modern technology. However, there are many things left to be examined and thought about with respect to the nature of the mind, what the substantial core of the mind is.” (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p23) “My concern is rather that that we are apt to overlook the limitations of science. In replacing religion as the final source of knowledge in popular estimation, science begins to look a bit like another religion itself… while both science and the law can help us forecast the likely consequence of our actions, neither can tell us how we ought to act in a moral sense. Moreover, we need to recognise the limits of scientific inquiry itself. For example, though we have been aware of human consciousness throughout history, despite scientists’ best efforts they still do not understand what it actually is, or why it exists, how it functions, or what is its essential nature”. (source: Dalai Lama (1999) Ethics for a New Millennium, cited in Mehrota, R. (ed.) (2006) The Essential Dalai Lama, London: Hodder Mobius, p9) “Just as scientific disciplines place tremendous emphasis on the need for objectivity on the part of the scientist, Buddhism also emphasises the importance of examining the nature of reality from an objective stance. You cannot maintain a point of view simply because you like it or because it accords with your preset metaphysical or emotional prejudices”. ”. (source: Dalai Lama (2002) Illuminating the Path to Enlightenment, cited in Mehrota, R. (ed.) (2006) The Essential Dalai Lama, London: Hodder Mobius,p43). “By inner values I mean the qualities that we all appreciate in others, and toward which we have a natural instinct, bequeathed by our biological nature as animals that survive and thrive only in an environment of concern, affection, and warm heartedness – or, in a single word, compassion.” (Source: Dalai Lama (2011) Beyond Religion: Ethics for a Whole World, London: Rider, ppxi) “When it comes to obtaining certain, direct results, it is clear that prayer cannot match, for instance, modern science. When I was ill some years ago, it was certainly comforting to know that people were praying for me, but it was, I must admit, still more comforting to know that the hospital where I was had the latest equipment to deal with my condition!” (Source: Dalai Lama (2011) Beyond Religion: Ethics for a Whole World, London: Rider, p4) “Many aspects of human existence, including values, creativity and spirituality, as well as deeper metaphysical questions, lie outside the scope of scientific inquiry… The view that all aspects of reality can be reduced to matter and its various particles is, to my mind, as much a metaphysical position as the view that there an organising intelligence created and controls reality”. (source: Dalai Lama (2005) The Universe in a Single Atom, London: Little Brown, p12) Questions for Reflection 1. How does the Dalai Lama’s view of the relationship between religion and science differ from those of other religions (if at all)? 2. Do you agree that origins of compassion and love can be explained by the theory of evolution? (How?) 3. 4. What do you think of the Dalai Lama’s view of prayer? How can Buddhism be said to be similar to science? The 14th Dalai Lama and other Religions This section will look at his views of other religions and his pluralistic vision of religion. He embodies empathy and tolerance for the views of others and his writings and activities support this. However, he is currently advocating the need for a secular global ethic ‘beyond religion’ and he contends that religious precepts and traditions are increasingly inadequate and parochial in the global village. The Dalai Lama has written that there is a universal humanity which has ideas of justice and compassion in common. For him different religious and philosophical views offer different cultural flavours in how this is expressed. He thinks these differences enrich global society, but if taken too seriously can lead to conflict and sectarianism. This perhaps contrasts with the views of certain religious figures, like Pope Benedict, who thinks that such variety leads to relativism, a situation where no-one can decide what is true or good anymore as there are too many different views to choose from. In contrast to this the Dalai Lama suggest we actually have a core shared humanity that is more important than any ‘local’ tradition, and that this is what humanity needs to recognise and put at the heart of our politics and religion in order to survive. Here are some quotes from the Dalai Lama on these issues: “So my true religion is kindness. If you practice kindness as you live, no matter if you are learned or not learned, whether you believe in the next life or not, whether you believe in God or Buddha or some other religion, in day to day life you have to be a kind person”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p41) “Every religion of the world has similar ideals of love, the same goal of benefiting humanity through spiritual practice, and the same effect of making their followers into better human beings. The common goal of all moral precepts laid down by the great teachers of humanity is unselfishness. All religions agree upon the necessity to control the undisciplined mind that harbors selfishness and other roots of trouble…. It is for these reasons that I have always believed all religions have essentially the same message. Therefore there is a great need to promote interfaith understanding, leading to respect for one another’s faith.” (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p64) “The Christians and Buddhists have basically the same teaching, the same aim. The world now becomes smaller and smaller, due to good communication… With that development different faiths and different cultures also come closer and closer. This is, I think, very good. If we understand each other’s way of living, thinking, different philosophies, and different faiths, it can contribute to mutual understanding. By understanding each other, naturally we will develop respect for one another… I always feel that this special inner development is something very important for mankind”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p9) “I maintain that every major religion of the world – Buddhism, Christianity, Confucianism, Hinduism, Islam, Jainism, Sikhism, Taoism, Zoroastrianism – has similar ideals of love, the same goal of benefiting humanity through spiritual practice, and the same effect of making their followers into better human beings. All religions teach moral precepts for perfecting the functions of mind, body and speech. All teach us not to lie or steal or take others’ lives and so on. The common goal of all moral precepts laid down by the great teachers is unselfishness”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p23) “We need to clearly recognise that the basic aim of all the religions is the same… It’s not at all good, and extremely unfortunate, to use the doctrines and practices that are for the sake of taming the mind as reasons for becoming biased. Therefore it is extremely important for us to be non-sectarian. As Buddhists, we need to respect the Christians, the Jews, the Hindus and so on. Also, among Buddhists we shouldn’t make distinctions and say that some are Theravadin and some are of the Great Vehicle and so forth”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p28) “Buddhists can’t make the whole world population become Buddhist. That’s impossible. Christians cannot convert all mankind to Christianity. And Hindus cannot govern all mankind. Over the past few centuries, if you look unbiasedly, each faith, each great teaching, has served mankind very much. So it’s much better to make friends and understand each other and make an effort to serve humankind rather than criticise or argue.” (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p69) “I think it’s helpful to have many different religions, since our human minds always likes different approaches for different dispositions. Just like food. There are some people who prefer bread and some who prefer rice and some who prefer flour. Each has different tastes… but there is no quarrel. Nobody says “Oh, you are eating rice”. In the same way, there is mental variety. So for certain people the Christian religion is more useful, more applicable… Some people say, “There’s a God, there’s a creator, and everything depends on His acts, so you should be impressed because of the creator”. If that sort of thing gives you more security, ore belief then you will prefer that approach… Also, certain people say that our Buddhist belief that there is no creator and everything depends on you, you should be impressed – that that is preferable… So from that point of view, it is better to have variety, to have many religions”. (source: Dalai Lama (1989) Ocean of Wisdom, Guidelines for Living, New York: Emery Printing, p85) “It is possible to manage without religion, and in some cases it may make life simpler! As long as we are human beings, and members of human society, we need human compassion. Without that you cannot be happy.” (source: Dalai Lama (1999) The Heart of the Buddha’s Path, cited in Mehrota, R. (ed.) (2006) The Essential Dalai Lama, London: Hodder Mobius,p24). Questions for reflection 1. Do you agree that all religions have the same aims? 2. Do you think religion is an ‘obstacle to human development? If so, why? 3. Is it possible to lose you ‘attachment’ to your own tradition or point of view when considering the views of others? Concluding quotations The following quotes capture some of the Dalai Lama’s wishes for the world and his understanding of his place in attempting to achieve them. “Because we all share this small planet Earth, we have to learn to live in harmony and peace with each other and nature. This is not a dream, but a necessity. We are dependent on each other in so many ways that we can no longer live in isolated communities and ignore what is happening outside these communities. We need to help each other when we have difficulties, and we must share the good fortune that we enjoy. I speak to you as just another human being; as a simple monk… If we selfishly pursue what we believe to be in our own interest, without caring about the needs of others, we not only end up harming others but also ourselves. This fact has become very clear during the course of this century. We know that to wage a nuclear war today for example, would be a form of suicide; or that by polluting the air or the oceans, in order to achieve some short-term benefit, we are destroying the very basis of our survival. As individuals and nations are becoming increasingly interdependent, therefore, we have no other choice than to develop what I call a sense of universal responsibility”. (source: Dalai Lama (1999) Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech, cited in Mehrota, R. (ed.) (2006) The Essential Dalai Lama, London: Hodder Mobius,pp13-14). “Reason, courage, determination, and the inextinguishable desire for freedom can ultimately win. In the struggle between the forces of war, violence and oppression on the one hand, and peace, reason and freedom on the other, the latter are gaining the upper hand. This realisation fills us Tibetans with hope that some day we too will once again be free”. (source: Dalai Lama (1999) Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech, cited in Mehrota, R. (ed.) (2006) The Essential Dalai Lama, London: Hodder Mobius,p16). “If we think of ourselves as very precious and absolute, our whole mental focus becomes very narrow and limited and even minor problems can seem unbearable. The actual beneficiary of the practice of compassion and caring for others is oneself”. (source: Dalai Lama (2002) Illuminating the Path to Enlightenment, cited in Mehrota, R. (ed.) (2006) The Essential Dalai Lama, London: Hodder Mobius,p29). “I am a seventy year old Buddhist monk and in a few months I will be seventyone. The greater part of my life has not been happy… when I was fifteen I lost my freedom; at the age of twenty-four I lost my country. Now forty one years have passed since I became a refugee and news from my homeland is always very saddening. Yet, inside, my mental state seems quite peaceful… This is not because I am some kind of special person… If we pay more attention to our inner world then our lives can be happier”. (source: Dalai Lama (2002) Illuminating the Path to Enlightenment, cited in Mehrota, R. (ed.) (2006) The Essential Dalai Lama, London: Hodder Mobius,p30). Websites for further research The role of the Dalai Lama on the BBC website Official Dalai Lama website Both sites contain summaries of the Dalai Lama’s beliefs, a biography and a number of video clips.