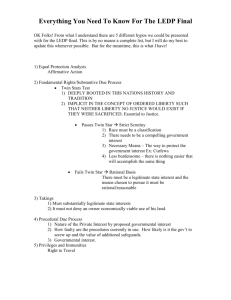

THE CURRENT STATUS OF HISTORICAL PRESERVATION LAW IN REGULATORY PRESERVATION PROGRAMS?

advertisement