n. EMPLOYEE BENEFITS FOR GENERAL PRACTITIONERS: TEN RULES THAT EVERY

advertisement

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS FOR GENERAL

PRACTITIONERS: TEN RULES THAT EVERY

ATTORNEY SHOULD KNOW ABOUT ERISA

by Jayne Elizabeth Zanglein°

I.

n.

m.

IV.

V.

VI.

VII.

VIII.

IX.

X.

XI.

INTRODUCTION................................

RULE #1: ERISA TRUMPS EVERYTHING-ALMOST ANY

STATE LAW CAUSE OF ACTION You CAN THINK OF WILL

BE PREEMPTED BY ERISA

RULE #2: WITH RESPECT TO REMEDIES, PARTICIPANTS ARE

WORSE OFF Now THAN THEY WERE BEFORE ERISA

WAS ENACTED

RULE #3: THERE IS AN EXCEPTION FOR EVERY RULESOME CLAIMS ARE NOT PREEMPTED BY ERISA

RULE #4: SOMETIMES THE FIFTH CIRCUIT WILL ApPLY

FEDERAL COMMON LAW TO A VOID THE EFFECTS OF

PREEMP110N . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..

RULE #5: "As CONGRESS GIVETH, CONGRESS

TAKETH AWAY"-SELF-FuNDED WELFARE PLANS GET

AWAY WITH ALMOST ANYTHING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..

RULE #6: DISCRIMINATION UNDER ERISA REQUIRES

SPECIFIC INTENT BY THE EMPLOYER TO INTERFERE WITH

ERISA BENEFITS

RULE #7: ONLY PARTICIPANTS, BENEFICIARIES, AND

FIDUCIARIES, BUT NOT INTENDED BENEFICIARIES, HAVE

STANDING TO SUE UNDER ERISA

RULE #8: UNDER MOST PLANS, THE PLAN ADMINISTRATOR

WILL HAvE DISCRETIONARY AUTHORITY TO CONSTRUE THE

TERMS OF THE PLAN, AND THEREFORE, THE STANDARD OF

REVIEW WILL BE ABUSE OF DISCRETION

RULE #9: FACTUAL DETERMINATIONS BY A PLAN

ADMINISTRATOR ARE REVIEWED FOR ABUSE OF

DISCRETION REGARDLESS OF PLAN LANGUAGE

RULE #10: ADVISORS WHO Do NOT HAVE AUTHORITY

AND CONTROL OVER PLAN ASSETS AND WHO Do NOT

RENDER REGULAR INVESTMENT ADVICE TO THE PLAN ARE

NOT FIDUCIARIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..

580

580

582

585

587

590

593

596

599

603

605

• Associate Dean and Professor of Law. Texas Tech Univenity School of Law. B.M.E.• Berldee

College of Music. 1975; J.D., State Univenity of New York at Buffalo. 1980.

579

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 579 1995

580

XII.

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26:579

CONCLUSION AND FINAL RULE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. 607

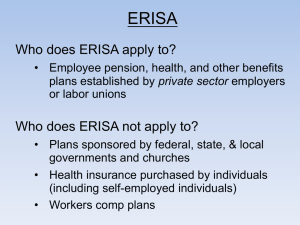

I. INTRODUCTION

This article, written on the eve of the twentieth anniversary of the

Employee Retirement Income Security Act (' 'ERISA' '), is a primer for nonERISA attorneys. Because ERISA is a complex statute that constantly

changes, it may seem fonnidable to some practitioners. After all, at least

according to legend, ERISA is an acronym for Every Ridiculous Idea Since

Adam. 1 But with a little guidance, ERISA issues that frequently arise in

general practice can be handled with confidence. Fortunately, the Fifth

Circuit's 1993-1994 tenn offers a good outline of issues for attorneys who

do not frequently work in this area.

II. RULE #1: ERISA TRUMPS EVERYTHING-ALMOST ANy STATE LAW

CAUSE OF ACTION You CAN THINK OF WILL BE PREEMPTED BY ERISA

ERISA preempts all state laws that relate to an employee benefit plan.2

The United States Supreme Court has broadly construed the preemption

clause, noting that it is "conspicuous for its breadth.,,3 As the Seventh

Circuit Court of Appeals stated: "Congress has blotted out (almost) all state

law on the subject of pensions, so [that] a complaint about pensions [or welfare

plans] rests on federal law no matter what label its author attaches.,,4 The

Fifth Circuit has noted that "[t]his sweeping preemption of state law is

consistent with Congress's decision to create a comprehensive, unifonn

federal scheme for the regulation of employee benefit plans.' ,s

1. One ridiculous idea that pops to mind is section 89. an amendment to the Internal Revenue

Code that sparked more controversy than any other ERISA legislation. Act of Oct. 22, 1986, 100 Stat.

2494 (repealed 1989); see Reform Bills Make Similar Mistakes as Section 89. Former Tax Aide Says, 19

BNA PENSION & BENBFITS REP. 448, 448 (Mar. 16, 1992). It was eventually abandoned after

implementation proved impossible. See id. at 448.

2. Employee Retirement Income Sewrity Act ("ERISA") § 514(a). 29 U.S.C. § 1144(a) (1988);

see District of Columbia v. Greater Washington Bd. of Trade, _ U.S. _' - ' 113 S. CL 580,583, 121

L. Ed. 2d 513, 520 (1992); Ingersoll-Rand Co. v. McClendon, 498 U.S. 133, 139 (1990); Pilot Life Ins.

Co. v. Dedeaux, 481 U.S. 41, 45-47 (1987); Shaw v. Delta Air Lines Inc., 463 U.S. 85,96-97 (1983).

ERISA's definition of an "employee benefit plan" includes pension and welfare plans. 29 U.S.C. §

1002(3) (1988).

3. FMC Corp. v. Holliday, 498 U.S. 52, 56-58 (1990); see also Shaw, 463 U.S. at 96

(recognizing breadth of ERISA's preemption) ; Alessi v. Raybestos-Manhattan, Inc., 451 U.S. 504, 52425 (1981) (finding New Iersey statute to be within the bounds of ERISA); Christopher v. Mobil Oil

Corp., 950 F.2d 1209, 1218 (5th Cir.) (recognizing broad interpretation of ERISA's preemption

provisions), cert. denied, _ U.S. --' 113 S. CL 68, 121 L Ed. 2d 35 (1992).

4. Bartholet v. Reishauer A.G. (Zurich), 953 F.2d 1073, 1075 (7th Cir. 1992).

5. Corcoran v. United HealthCare, Inc., 965 F.2d 1321, 1329 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, _ U.S.

--' 113 S. Ct. 812, 121 LEd. 2d 684 (1992); see McClendon, 498 U.S. at 142; Dedeaux, 481 U.S. at

45-46.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 580 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

581

Although there is absolutely no doubt that ERISA preempts all state law

claims that relate to an employee benefit plan (with some exceptions for

insurance, banking, securities,6 and general criminal laws?), courts decide

hundreds of ERISA preemption cases each year. The number of preemption

cases is startling, given that the law is well settled in this area. s For

example, this term, the Fifth Circuit decided six preemption cases. 9 In

Anderson v. Electronic Data Systems Corp.,1° the Fifth Circuit noted,

"[We] are hardly writing on a clean slate, as the subject of federal

preemption under ERISA has generated a wealth of jurisprudence. "11 Yet,

the issue keeps reappearing, as if plaintiffs believe that by sheer force of

repetition, the law will change. More likely, plaintiffs' attorneys believe that

if given just the right sympathetic facts, judges might ignore preemption and

rule with the heart instead of the mind. 12

This is unlikely to happen. The Fifth Circuit has heard numerous

ERISA cases about hapless participants who have been wronged by

unscrupulous employers or insurers. In fact, the Fifth Circuit has dubbed

these hapless participants as "betrayed without a remedy. "13 The Fifth

Circuit has been reluctant to expand federal common law under ERISA to

provide remedies for these remediless participants. For example, in

Corcoran v. United HealthCare, inc.,14 the Fifth Circuit preempted a

lawsuit brought by a grieving couple for the wrongful death of their unborn

child. 15 The couple alleged that the fetus's death was caused by a negligent medical decision made by a utilization review company.16 The Fifth

Circuit held that ERISA preempted the wrongful death claim and said that

"[t]he acknowledged absence of a remedy under ERISA's civil enforcement

6. 29 U.S.C. § 1144(b)(2)(A) (1988).

7. Id. § 1144(b)(4).

8. Of course, there are always cases of first impression. However, most of the cases discussed

in this article relate to routine preemption issues which courts have previously addressed.

9. Anderson v. Electronic Data Sys. Corp., 11 F.3d 1311 (5th Cir. Jan.), cert. denied, _

U.S.

_, 115 S. Ct. 55, 130 L. Ed. 2d 14 (1994); Bulks v. Amerada Hess Corp., 8 F.3d 301 (5th Cir. Dec.

1993); Perdue V. Burger King Corp., 7 F.3d 1251 (5thCir. Dec. 1993); Epps v. NCNB Texas, 7 F.3d44 (5th

Cir. Oct. 1993); NGS Am., Inc., v. Barnes, 998 F.2d 296 (5th Cir. Aug. 1993); Tingle v. Pacific Mut.Ins.

Co., 996 F.2d 105 (5th Cir. July 1993).

10. 11 F.3d 1311 (5th Cir. Jan. 1994).

11. Id.atI313.

12. In Smith v. Hartford Insurance Group, 6 F.3d 131 (3d Cir. 1993), Judge Hutchinson, in a

dissenting opinion, commented: "Logic may be the law's tool but its heart is justice, and the public's

demand for concrete justice will not be contained by the straitjacket of inflexible rules." Id. at 146

(Hutchinson, J., dissenting).

13. Degan v. Ford Motor Co., 869 F.2d 889, 895 (5th Cir. 1989).

14. 965 F.2d 1321, 1333 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, _

U.S. _,113 S. Ct. 812, 121 L. Ed. 2d

684 (1992).

15. Id. at 1331.

16. Id. at 1326.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 581 1995

582

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26:579

scheme ... does not alter our conclusion.';17 The court held that "[w]hile

we are not unmindful of the fact that our interpretation of the preemption

clause leaves a gap in remedies within a statute intended to protect

participants in employee benefit plans, the lack of an ERISA remedy does

not affect a preemption analysis.',18 Likewise, in Hansen v. Continental

Insurance CO.,19 the Fifth Circuit held that "ERISA's preemption provision

bars state law causes of action even though such preemption may leave a

victim ... without a remedy,',20

III. RULE #2: WITH RESPECT TO REMEDIES, PARTICIPANTS ARE WORSE

OFF Now THAN THEY WERE BEFORE ERISA WAS ENACTED

Although it seems unfair that participants are worse off with respect to

remedies than they were twenty years ago before the passage of ERISA, this

is the current state of the law. 21 Before ERISA, plaintiffs had a full range

of remedies to choose from under state and federal law. After ERISA, as

interpreted by the Supreme Court, plaintiffs have fewer remedies. 22 ERISA

does not provide for extra-contraetual23 or punitive damages,24 so there

is little to deter an unscrupulous employer or insurer. Basically, ERISA

allows a participant to sue to recover an unpaid benefit,25 but does not

allow any other monetary damages.2Ci In some cases, the participant cannot

directly receive any recovery. For example, where a participant alleges a

breach of fiduciary duty, any recovery goes to the plan, not the individual.27

This lack of remedies is exacerbated by the preemption of state law claims.

In suits for negligence,28 violation of the Deceptive Trade Practices Aet,29

intentional infliction of emotional distress,30 misrepresentation,31 tortious

17.

18.

Jd. at 1333.

Jd. (citations omitted).

19. 940 F.2d 971 (5th Cir. 1991).

20. Jd. at 979.

21. See Labor Department Reviews Cases in Effort to Help Determine Law. 21 BNA PENSION

& BBNEfITS REp. 1689. 1689 (Sept. 12. 1994).

22. See Jayne Zanglein. Closing the Gap: Safeguarding Participants' Rights by Expanding the

Federal Common Law of ERlSA. 72 WASH. U. LQ. 671 (1994). for a more detailed analysis of this

problem.

23. Massachusetts Mut. llie Ins. Co. v. Russell. 473 U.S. 134. 148 (1985).

24. Jd.

25. 29 U.S.C. § 1102(a)(1)(B) (1988).

26. Mertens v. Hewitt Assoc., _ U.S. -..J -..J 113 S. Ct. 2063. 2066-68. 124 L Ed. 2d 161.

167-69 (1993).

27. Russell. 473 U.S. at 144.

28. E.g., Ramirez v. Intercontinental Hotels, 890 F.2d 7(1.). 762-63 (5th Cir. 1989).

29. E.g .• id.

.

30. E.g .• Burks. 8 F.3d at 305; Brown v. Southwestern Bell Tel. Co., 901 F.2d 1250. 1254 (5th

Cir. 1990).

31. E.g .• Degan, 869 F.2d at 893.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 582 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

583

interference,32 unfair claims practices,33 breach of contract,34 wrongful

death,3s and wrongful discharge,36 ERISA preempts state law without

providing an adequate remedy.

For example, this term in Anderson v. Electronic Data Systems, Corp.,

the Fifth Circuit held that Anderson's claim that he was demoted and

discharged for refusing to violate ERISA and for whistleblowing was

preempted by ERISA. 3? The Fifth Circuit relied on Ingersoll-Rand Co. v.

McClendon,38 in which the Supreme Court held that a law "relates to" an

ERISA plan, and is therefore preempted, "if it has a connection with or

reference to such a plan...39 The Fifth Circuit held that Anderson's

wrongful discharge claim was preempted because it was "based on his

refusals to carry out violations of ERISA."4O Because Anderson's claim

depended on the existence of a pension plan, it "relate[d] to" an ERISA

plan and was preempted.41 The court also noted that a state cause of

action for wrongful discharge would conflict with the antidiscrimination rule

found in ERISA section 510.42 The court said that "such a finding of

preemption does not hinge on whether ERISA provides the remedy the

plaintiff seeks or any remedy at all for the alleged wrong.' ,43

At first blush, the preemption of Anderson's wrongful discharge case

might appear logical because he mentioned ERISA in his original complaint.

However. Anderson was not an ERISA case. It was a wrongful discharge

case for which Anderson might have recovered substantial damages, if

successful. Under ERISA, however, extra-contractual or punitive damages

are unavailable, so the only remedy would have been for Anderson to return

32.

E.g., Kuhl v. Lincoln Nat'l Health Plan, Inc., 999 F.2d 298,302·03 (8th Cir. 1993), cerr.

U.S.

, Il4 S. Ct. 694, 126 L Ed. 2d 661 (1994).

3~E.g., ~e v. Connecticut Gen. Life Ins. Co., 867 F.2d 489, 493-94 (9th Cir. 1988), cert.

denied, 492 U.S. 906 (1989).

34. E.g., Kuhl, 999 F.2d at 302-03; Cromwell v. Equicor-Equitable HCA Corp., 944 F.2d 1272,

1275 (6th Cir. 1991); Powell v. Chesapeake & Potomac Tel Co., 780 F.2d 419, 421-22 (4th Cir. 1985),

cert. denied, 476 U.S. Il70 (1986); Shaw v. InCI Ass'n of Machinists & Aerospace Workers Pension

Plan, 563 F. Supp. 653, 658-59 (C.D. Cal. 1983), affd, 750 F.2d 1458 (9th Cir.), cert. denied, 471 U.S.

Il37 (1985).

35. E.g., Corcoran, 965 F.2d at 1333.

36. E.g., Anderson, II F.3d at 1314.

37. Id. Anderson alleged that he was discharged for refusing to sign pension checks without the

approval of the trustees and for refusing to write minutes for meetings that he did not attend. Id. at 1312.

Anderson alleged that such actions would have violated ERISA. Id. Later, Anderson amended his

complaint and deleted all references to ERISA. Id. at 1313.

38. 498 U.S. 133 (1990).

39. Id. at 139 (quoting Shaw, 463 U.S. at 96-97).

40. Anderson, II F.3d at 1314.

41. Id.

42. 29 U.S.C. § 1140 (1988).

43. Anderson, II F.3d at 1314.

denied,

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 583 1995

584

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26:579

to work for an employer who he believed was dishonest and who fired him

for blowing the whistle.

In Burks v. Amerada Hess COrp.,44 the Fifth Circuit held that an

employee's claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress arising from

a wrongful termination was preempted by ERISA. 45 Originally, Burks

filed a complaint alleging that he had been wrongfully fired in retaliation for

filing a worker's compensation claim.46 In his original complaint, Burks

alleged that as a result of his discharge, he lost pension and medical benefits

that he otherwise would have accrued,47 Later, he amended the complaint

to delete any references to the loss of pension and medical benefits. but still

alleged that his employer improperly denied his long-term disability

benefits.48

The Fifth Circuit preempted Burk's claim for intentional infliction of

emotional distress, stating that the claim was preempted because it was

based on the employer's alleged denial of long-term disability benefits.49

The court noted: "This is not a case in which the loss of benefits is merely

an element in damages related to a claim for wrongful discharge.' ,so The

court expressed its displeasure that Burks engaged in "forum manipulation.' ,51 The court found that Burks engaged in an obvious and somewhat

frantic maneuver to avoid federal jurisdiction.52 The court stymied Burks'

attempt at forum manipulation by denying his motion to remand. 53

In Epps v. NCNB Texas,S4 the Fifth Circuit noted that "[w]hen a court

must refer to an ERISA plan to determine the plaintiff's retirement benefits

and compute the damages claimed, the claim relates to an ERISA plan.' ,55

The court held that even though Epps did not mention ERISA or specifically

refer to an employee benefit plan in his complaint, his claim for breach of

obligation to pay severance benefits was preempted.56 The court determined that preemption was appropriate because Epps sued to recover' 'loss

of pension and retirement benefits which would have accrued and vested"

44.

8 F.3d 301 (5th Cir. Dec. 1993).

45.

46.

47.

48.

[d. at 304-OS.

[d. at 303.

[d.

[d.

49. [d. at 305. The court held that "[a] state [law] cause of action for emotional distress arising

from the denial of employee benefits determines when an employer can and cannot terminate an

employee's benefits," [d.

50. [d. The court explained that "[a] claim that unlawful termination resulted in loss of benefits

is not preempted by ERISA," [d. at 306.

51. [d.

52. [d.

53. [d.

54. 7 F.3d 44 (5th Cir. Oct. 1993).

55. [d. at 45 (citing Christopher, 950 F.2d at 1218-20).

56. [d.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 584 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

585

if the employer had not breached the employment contract. S7 The court

held that because it would have been required to refer to the pension plan

to calculate the damages claimed, the claim was preempted.58 Likewise,

in Perdue v. Burger King COrp.,59 the court held that a common law fraud

claim was preempted "because the only damages recoverable under the

claim 'relate[d] to' the value of severance benefits" under an employee

benefit plan.60

IV. RULE #3: THERE IS AN EXCEPTION FOR EVERY RULE-SOME

CLAIMS ARE NOT PREEMPTED BY ERISA

Caution, however. For every rule, there is an exception! Not all state

causes of action will be preempted. Occasionally, the Fifth Circuit will hold

that a state law claim is not preempted because it does not "relate to" a

plan. This term, in Perdue, the court held that ERISA did not preempt a

claim for breach of an agreement to confer a franchise because it did not

relate to a plan.61

Similarly, in Weaver v. Employers Underwriters, Inc.,62 the Fifth

Circuit held that ERISA did not preempt the claims of an independent

contractor who was neither a participant nor a beneficiary and thus not a

person traditionally protected under ERISA. Jimmy Weaver was hired by

Malcolm Rodrigues as a saw hand to fell lumber for an unincorporated

logging business. 63 Rodrigues identified Weaver as a subcontractor for

purposes of federal income tax and social security taxes. 64 Rodrigues

became a member of a multi-employer medical plan that provided benefits

to Rodrigues and his employees.65 The plan covered all employees who

worked an average of one or more hours a week. 66

Weaver was injured by a falling tree. 67 He applied for and began

receiving benefits under the plan. 68 Later, Rodrigues informed the insurer

that Weaver was not an employee and payments ceased.69 The insurer

57. Id.

58. Id.

59. 7 F.3d 1251 (5th Cir. Dec. 1993).

60. Id. at 1255-56.

61. Id. at 1256.

62. 13 F.3d 172, 176 (5th Cir. Feb.), cerr. denied, _

866 (1994).

63. Id. at 173.

64. Id. at 174.

65. Id.

66. Id.

67. Id.

68. Id.

69. Id.

U.S. - ' 114 S. Ct. 2137. 128 L. Ed. 2d

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 585 1995

586

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26:579

negotiated a lump sum settlement with Weaver?O Weaver was dissatisfied

with the settlement and sued Rodrigues, the insurer, and an insurance

adjuster. Weaver alleged, among other things, violation of the Texas

Deceptive Trade Practices Act due to false, misleading, and deceptive

practices in the settlement of his claim, violation of the Texas Insurance

Code due to the alleged grossly inadequate settlement, duress, bad faith,

conspiracy to deceive, and negligence in failing to provide a safe workplace

and safe equipment.71 The district court preempted all of Weaver's claims

except those relating to unsafe working conditions and inadequate equipment

and held that Weaver had no standing to bring an ERISA claim.72

Weaver appealed, arguing that as an independent contractor, he was

covered by the plan, but that the portion of the plan that covered nonemployees was not an ERISA plan; therefore, his claims were not preempted.73 The Fifth Circuit acknowledged that a Rhode Island district court

"ha[d] held that a plan can be divided into ERISA and non-ERISA portions. ,,74 The court held that ERISA did not preempt Weaver's claims, but

declined to rule, however, on the issue of whether a plan may be split into

ERISA and non-ERISA parts.7S

The court held that ERISA preempts state law claims if two factors are

present: "(1) the state law claims address areas of exclusive federal

concern, such as the right to receive benefits under the terms of an ERISA

plan; and (2) the claims directly affect the relationship between the

traditional ERISA entities - the employer, the plan and its fiduciaries, and

the participants and beneficiaries.' ,76

Both factors must be present. The court held that the second factor was

not present here: the claims of an independent contractor do not "directly

affect the relationship between the traditional ERISA entities.',n Weaver

was not a participant in the plan because he was not an employee.78

ERISA defines a participant as:

[A]ny employee or former employee of an employer, or any member or

former member of an employee organization, who is or may become

eligible to receive a benefit of any type from an employee benefit plan

which covers employees of such employer or members of such organiza-

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

1993».

[d.

[d.

[d.

[d. at 174-75.

•

[d. at 175 (citing Kelly v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield, 814 F. Supp. 220, 227-29 (D. R.I.

75. Weaver. 13 F.3d at 175.

76.

Cir. 1990)

77.

78.

[d. at 176 (citing Memorial Hasp. Sys. v. Northbrook Life Ins. Co.• 904 F.2d 236, 245 (5th

(footnotes omitted».

[d.

[d.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 586 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

587

lion, or whose beneficiaries may be eligible to receive any such benefit79

This definition clearly focuses on the employer-employee relationship.

Weaver was an independent contractor, not an employee; therefore, he could

not be a participant.80

The court also ruled that Weaver was not a beneficiary.81 ERISA

defines a beneficiary as "a person designated by a participant, or by the

tenns of an employee benefit plan, who is or may become entitled to a

benefit thereunder... 82 Weaver did not fall within this definition of

beneficiary.83

The court noted that the claims of a nonparticipant and nonbeneficiary

such as Weaver "do not affect the relationship between the traditional

ERISA entities" and are not preempted. 84 As previously noted, individuals

are better off, in some respects, if they are not covered by ERISA.

V. RULE #4: SOMETIMES THE FIFrH CIRCUIT WILL ApPLY FEDERAL

COMMON LAW TO AVOID THE EFFECTS OF PREEMPTION

In Brandon v. Travelers Insurance CO.,8S a case of first impression

with surprising results, the Fifth Circuit applied federal common law to

detennine that an ex-spouse was not entitled to receive benefits under a life

insurance plan even though she was designated as a beneficiary under the

tenns of the plan.

The court's opinion took some strange turns and twists. First (and

predictably), the court held that ERISA preempts state laws relating to the

transfer of property on divorce. 86 The court held that ERISA preempts a

Texas Family Code provision87 that requires a life insurance plan participant to redesignate an ex-spouse after divorce in order to maintain that exspouse as the designated beneficiary.88

Richard Brandon designated his wife, Wanda, as a beneficiary of a life

insurance policy offered through his employer.89 At the time of the

designation, the Brandons were separated.90 Richard told Wanda that she

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

29 U.S.C. § 1002(1) (1988).

Weaver. 13 F.3d at 176.

Id. at 177.

29 U.S.C. § 1002(8) (1988).

Weaver, 13 F.3d at 177.

84.

Id.

18 F.3d 1321 (5th Cir. Apr. 1994).

Id. at 1326.

TEX. FAM. CODE ANN. § 3.632 (Vernon 1993).

Brandon, 18 F.3d at 1326.

Id. at 1323.

Id.

85.

86.

87.

88.

89.

90.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 587 1995

588

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26:579

would remain the designated beneficiary even if they divorced. 9l The

Brandons divorced. 92 According to the divorce decree, each spouse would

separately retain his or her own employment benefits.93 The divorce decree

specifically divested Wanda of all rights in any "benefit program existing by

reason of [Richard's] past, present or future employment. "94 The Brandons

were on friendly terms and continued to socialize.9s Richard aid not change

his designation of Wanda as his beneficiary.96 When Richard died, his

employer notified Wanda that she was the designated beneficiary.97 Wanda

applied for the life insurance benefit. 98 Later, Wanda discovered that the

benefit had been paid to Richard's brother, Gary, who was listed as a

contingent beneficiary.99 Richard's employer paid Gary because Richard

had not redesignated Wanda as his beneficiary after the divorce, as required

by Texas Family Code section 3.632. 100 Wanda sued. 101 The district

court held that Wanda was not entitled to the life insurance because the

divorce decree, which determined her rights, divested her of those benefits. 102

The plan required the employer to "pay the insurance proceeds to the

designated beneficiary unless for specified reasons the administrator

determine[d] that the contingent beneficiary should be paid. ,,103 Therefore, under the terms of the plan, Wanda, as the designated beneficiary,

should have been entitled to the benefit

The Fifth Circuit rejected the employer's contention that the Texas

Family Code requires a redesignation of an ex-spouse after divorce to

maintain the ex-spouse as the designated beneficiary of a life insurance

policy.l04 The court held that ERISA preempts the Texas Family Code

provision because that provision "relates to" an employee benefit plan. lOS

So far, so good. But here's where the case took some swprising turns.

Next, the court considered whether ERISA controlled exclusively or whether

federal common law applied. lOO The court noted that the circuit courts

Id.

92. Id.

93. Id.

94. Id.

95. Id.

96. Id.

97. Id.

98. Id.

99. Id.

100. Id.

101. Id.

102. Id.

103. Id. at 1324.

104.· Id. at 1324-25.

105. Id. at 1325; see supra text accompanying notes 2-20 for a mon: exh8l1stive diSalSSion of

preemption.

106. Brandon, 18 F.3d at 1325.

91.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 588 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

589

have taken two different approaches. 107 Some, like the Sixth Circuit,

apply strict statutory construction. IDS Other courts, like the Seventh and

Eighth Circuits, look to federal common law to achieve a more equitable

result. I09

The court· first examined the strict statutory construction approach

adopted by the Sixth Circuit in McMillan v. Parrot. IlO ERISA section

404(a)(l)(D) requires a plan administrator to administer the plan "in

accordance with the documents and instruments governing the plan. ,,111

The Sixth Circuit held that ERISA section 404(a)(l)(D) requires plan

administrators to follow plan documents, and when a conflict arises between

plan documents and a divorce decree, the plan documents govem. 112 The

Sixth Circuit reasoned that the "clear statutory command, together with the

plan provisions, answer the question; the documents control, and those name

[the ex-wife]. ,,113

Next. the Fifth Circuit examined the more liberal approach taken by the

Seventh Circuit in Fox Valley & Vicinity Construction Workers Pension

Fund v. Brown 1l4 and the Eighth Circuit in Lyman Lumber Co. v. Hill. ll5

Those courts examined whether" a valid, specific waiver of benefits in the

divorce decree" had occurred and whether the court could give effect to this

waiver under federal common law. 116 In Fox Valley, the Seventh Circuit

looked to Illinois family law which provided that a divorce decree will not

affect pension rights unless the decree specifically tenninated those

rights. 117 The court held that "the ability of a spouse to waive rights to

a benefit through a specific waiver in a divorce settlement has been recognized by many [state] courts and we adopt that rule for purposes of

ERISA. "liS

The Fifth Circuit adopted the reasoning of Fox Valley and applied the

Texas Family Code's "presumption of waiver absent redesignation

following divorce. ,,119 However, the court cautioned that "any waiver of

107. [d.

108. [d. at 1325-26 (citing McMillan v. Parrott. 913 F.2d 310 (6th Cir. 1990».

109. [d. at 1326 (citing Fox Valley & Vicinity Constr. Workers Pension Fund v. Brown, 897 F.2d

275 (7th Cir.) (en bane). cert. denied. 498 U.S. 820 (1990); Lyman Lumber Co. v. Hill, 877 F.2d 692

(8th Cir. 1989».

110. 913 F.2d 310 (6th Cir, 1990).

11 I. 29 U.S.c. § 1100(a)(I)(O) (1988 & Supp. V 1993).

112. Brandon. 18 F.3d at 1325.

113. [d. at 1326 (quoting McMillan, 913 F.2d at 311).

114. 897 F.2d 275. 280 (7th Cir.) (en bane). cert. denied. 498 U.S. 820 (1990).

115. 877 F.2d 692 (8th Cir. 1989).

116. Brandon. 18 F.3d at 1326.

117. [d. (citing Fox Valley. 897 F.2d at 281-82).

118. [d. (citing Fox Valley. 897 F.2d at 281).

119. Jd.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 589 1995

590

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26:579

ERISA benefits [must] be explicit, voluntary, and made in good faith. "120

The court found that Wanda Brandon had explicitly and voluntarily waived,

in good faith, her right to the insurance proceeds, even though she did not

attend the divorce proceedings: "The divorce decree was a bona fide

waiver of her rights to the insurance policy proceeds and we are bound to

cany out the provisions of the agreement signed by the parties.' ,121

Therefore, Wanda was not entitled to the proceeds of the life insurance.

As a strong advocate of the application of federal common law to fill

in the gaps in ERISA,122 I applaud the use of federal common law to

achieve more equitable results in ERISA cases. However, it seems strange

that Brandon applied federal common law since ERISA clearly provides that

the plan documents control and since the attorneys involved in the case

should have known the effect of ERISA on divorce decrees and qualified

domestic relations orders. 123 What was unusual in Brandon was that the

court used federal common law to clearly act against the wishes of the

participant and the beneficiary to reach an unintended and contrived result.

Brandon presents a case where the beneficiary wins under a preemption

analysis and then loses when the court applies federal common law.

Meanwhile, plaintiffs like Anderson who are discharged for whistleblowing

are "betrayed without a remedy," lost in the black hole left by federal

preemption and inadequate remedies. The moral: It is difficult for a participant or a beneficiary to win in the Fifth Circuit.

VI. RULE #5: "As CONGRESS GIVETH, CONGRESS TAKETH

AWAy"I24_S ELF-F'UNDED WELFARE PLANS GET AWAY WITH ALMOST

ANYTHING

Self-funded employee benefit welfare plans (Le., medical plans) exist

in the best of all possible worlds. They are not required to comply with

state-mandated benefit laws, and they are exempt from state laws relating

to taxes and fees.

ERISA's preemption clause contains an "insurance savings clause"125

that provides that nothing in ERISA "shall be construed to exempt or

relieve any person from any law of any state which regulates insurance,

120. ld. at 1327.

121. ld.

122. See Jayne Zanglein. Closing the Gap: Safeguarding Participants' Rights by Expanding the

Federal C011l1TlOn lAw of ERISA. 72 WASH. U. L.Q. 671 (1994) for a more detailed analysis of this

problem.

123. In fact, it is possible that an astlne lawyer might have advised Richard Brandon not to worry

about the redesignation of Wanda as his designated beneficiary because ERISA preempts the Texas

Family Code provision.

124. NGS Am., Inc. v. Bames. 998 F.2d 296 (5th Cir. Aug. 1993).

125. 29 U.S.C. § 1144(b)(2)(A) (1988).

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 590 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

591

banking, or securities."126 In Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. v. Massachusetts,127 the Supreme Court held that a state law that required insurance

companies to provide mandated mental health benefits fell within the

insurance savings clause and was not preempted by ERISA. 128 However,

the Court noted that insured plans and self-funded plans are subject to

different regulation because of ERISA's deemer clause. 129 The deemer

clause provides that ERISA plans should not be deemed to be insurance

companies. 130 The effect of the deemer clause is that insured plans are

subject to state insurance regulation, but self-funded plans are not.

In NGS American, Inc. v. Barnes,l3l the Fifth Circuit held that ERISA

preempts article 21.07-6 of the Texas Insurance Code as applied to

administrators of self-funded ERISA plans. 132 Article 21.07-6 imposes

regulations, fees, and taxes on self-funded ERISA plans and their administrators. 133 The Fifth Circuit described a two-pronged test that determines

whether a state insurance law is saved from preemption by ERISA's savings

clause. l34 First, the court must determine if the statute meets a common

sense defmition of insurance regulation. 13S Second, the court must

consider three factors: "(1) whether the state statute spreads the policyholder's risk; (2) whether the state statute is an integral part of the policy

relationship between the insurer and the insured; and (3) whether the

practice is limited to entities within the insurance industry. ,,136 If the

statute meets the first prong and all three parts of the second prong, the

statute falls within ERISA's savings clause and is not preempted. 137

The court applied the test to article 21.07_6. 138 Because the Commissioner of Insurance had conceded that plan administrators of self-insured

plans subject to regulation under article 21.07-6 perform no risk-bearing

function, the court concluded that the first part of the second prong of the

126.

Id.

127.

471 U.S. 724 (1985).

128. Id. at 744.

129. Id. at 747. Employers may fund medical benefits in two ways: self-insure or purchase

insurance. NGS Am., 998 F.2d at 298. In Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., the Supreme Court held that

insured plans are subject to regulation by state insurance laws, but self-funded plans are noL

Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 471 U.S. at 739-47.

130. 29 U.S.c. § I I44(b)(2)(B) (1988).

131. 998 F.2d 296 (5th Cir. Aug. 1993).

132. Id. at 300; see also Self-Insurance Institute of Am. Inc. v. Korioth, 993 F.2d 479 (5th Cir.

June 1993) (involving a challenge to article 21.07-6).

133. TEX. INS. CODB ANN. art. 21.07-6 (Vemon 1986 & Supp. 1994).

134. NGS Am., 998 F.2d at 299.

135. Id.

136. Id.

137. Id.

138. Id.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 591 1995

592

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26:579

test could not be met: the law did not spread risk among policyholders. 139

Therefore, the plan could not fall within ERISA's savings clause. 140

Next, the court rejected the Commissioner's argument that article

21.07-6 does not "relate to" an employee benefit plan because it applies to

both insured and self-funded plans. 141 Article 21.07-6 provides that the

Commissioner may review the fmancial records of the administrator and

may examine all written agreements between the plan and its insurers. 142

The statute also allows the Commissioner to audit the administrator's books

and records. 143 The court held that it was just these types of "burdens of

complying with conflicting state regulations that Congress sought to

eliminate by enacting ERISA. ,,144 The court held that the statute "related

to" an employee benefit plan and, therefore. was preempted by ERISA. 145

Tingle v. Pacific Mutual Insurance CO.,146 another preemption case

involving the insurance savings clause, might be subtitled "The Case of the

$71,300 Girdle." Mrs. Tingle injured her back while attempting to put on

her girdle. 147 She was operated on for a herniated disk and incurred

$71,300 in medical expenses. 148

Her husband submitted her claims to Pacific Mutual Insurance

Company ("Pacific") for payment. 149 Pacific investigated Mrs. Tingle's

139. The court did not evaluate whether any other parts of the test had been met. Id.

140. Id.

141. Id.

142. Id. at 299-300.

143. Id. at 300.

144. Id. (citing Shaw. 463 U.S. at 105).

145. NGS Am., 998 F.2d at 300. The court noted that the Commissioner could still enforce

article 21.07-6 against third party administrators of non-ERISA governed insurance plans, or against third

party administrators of both ERISA and non-ERISA govemed plans in their capacity as administrators

of non-ERISA governed plans. Id.

Another case this tenn dealt with Texas Insurance Code article 21.07-6. In Self-lnsuranL:e Institute

of America. Inc. v. Korioth. the Fifth Circuit held that a California not-for-profit trade association

organized to advance the self-insurance industry had standing to challenge article 21.07-6. 993 F.2d 479,

484-85 (5th Cir. June 1993). The court relied on Hunt v. Washington Apple Advertising Commission,

432 U.S. 333 (I9n), in which the Supreme Court held that a trade group has associational standing to

sue when: (a) its members would otherwise have standing to sue in their own right; (b) the interests it

seeks to protect are gennane to the organization's purpose; and (c) neither the claim asserted nor the

relief requested requires the participation of individual members in the lawsuit. Korioth, 993 F.2d at 484

(citing Hunt, 432 U.S. at 343). The court also relied on Data Processing Service Organization v. Camp,

in which the Supreme Court held that "a plaintiff that seeks standing to maintain an action alleging

violations of a federal statute must: (i) suffer injury in fact; and (ii) fall within the zone of interest

protected by the statute." Id. (relying on Camp, 397 U.S. 150 (1970». The Fifth Circuit held that the

association's members had been affected by article 21.07-6 and were within ERISA's zone of interests.

Id. The court noted that because the association's members were considered fiduciaries under Texas law,

they constituted an enumerated party under section 502. Id. The court held that the trade association

had associational standing to bring the case. Id. at 484-85.

146. 996 F.2d 105 (5th Cir. July 1993).

147. Id. at 106.

148. Id.

149. Id.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 592 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

593

medical history and discovered some discrepancies between her medical

history and her insurance enrollment fonns. ISO Pacific denied her claims

and retroactively cancelled the policy, alleging that misrepresentations were

made on the enrollment fonn. lsl Tingle sued. ls2

The Fifth Circuit held that ERISA preempts a Louisiana state law that

allows an insurer to refuse payment because of a false statement in an

application fonn if the statement was made with actual intent to deceive or

to materially affect acceptance of risk or hazard assumed by the insurer. ls3

The court held that the statute did not fall within ERISA's insurance savings

clause, and, therefore, was preempted. lS4

The court looked at the two-pronged test set forth in Metropolitan

1SS

Life.

The court held that because the statute did not have the effect of

spreading policyholders' risks, it did not meet the first prong of the test. IS6

The court noted that "[a]lthough the statute does shift the burden of

innocent misrepresentations (the legal risks) onto the insurer, it does not

spread the risk of insurance (health) coverage for which the parties

contracted. "157 Therefore, the statute was preempted. 1S8

VII. RULE #6: DISCRIMINATION UNDER ERISA REQUIRES SPECIFIC

INTENT BY THE EMPLOYER TO INTERFERE WITH ERISA BENEFITS

Section 510 of ERISA prohibits an employer from discharging,

expelling, or discriminating "against a participant ... for the purpose of

interfering with the attainment of any right to which such participant may

become entitled under the plan .... ' '159 The Fifth Circuit has frequently

held that although an employer's conduct might appear to be discriminatory,

it is not discriminatory per se simply because it adversely affects a class of

participants or because it is motivated by the employer's desire to cut costs

under the plan. 160 For example. in McGann v. H & H Music CO.,161 the

Fifth Circuit held that an employer did not violate section 510 when it

150. Jd.

151. Jd.

152. Jd.

153. Jd. at 108; see LA. REv. STAT. ANN. § 22:619 (West 1978 & Supp. 1994).

154. Tingle, 996 F.2d at 108.

155. Jd. at 107-09.

156. Id. at 108.

157. Id.

158. Id.

159. 29 U.S.C. § 1140 (1988).

160. But see Stephen Allen Lynn, P.e. Employee Profit Sharing Plan & Trost v. Stephen Allen

Lynn, P.C., 25 F.3d 280, 284 (5th Cir. 1994) (holding that across-the-board plan amendments that

prevented a sole proprietor's estranged wife from becoming a beneficiary violated section 510).

161. 946 F.2d 401 (5th Cir.), cerro denied, _

U.S. _ ' 113 S. CL 482, 121 L. Ed. 2d 387

(1992).

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 593 1995

594

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26:579

reduced medical benefits for participants with AIDS.162 The court noted

that in enacting ERISA, Congress did not require the vesting of medical

benefits so as to encourage employers to create medical plans. 163 Furthermore, the court held that section 510 requires proof of specific intent to

discriminate against the plaintiff, rather than general allegations that the

employer's action adversely affected a particular class of participants!64

Later, in Unida v. Levi Strauss & CO.!6S the Fifth Circuit held that an

employer's decision to close a plant to avoid increased employee benefits

costs was not sufficient to prove that the employer violated section 510 of

ERISA. 166

This term, in Perdue v. Burger King Corp., the Fifth Circuit reiterated

that specific intent is required to prove discrimination under ERISA. I67

In April 1989, Burger King Corporation ("BKC") eliminated several

management tiers including all Franchise Area Manager positions.168 At

the same time, BKC created the Burger King Job Elimination Program, a

severance plan that offered severance benefits to "any full-time employee

who loses his job as a result of a job elimination plan or reduction in a

workforce."169 Perdue, a Franchise Area Manager, was given the option of

either staying on with BKC as a Franchise Operations Manager or receiving

a severance benefit under the program.170 He decided to remain with

BKC and become the Franchise Operations Manager. l71

At the time Perdue switched positions, he owed BKC $1,000 for

unused travel advances. 172 He contacted the BKC accounting department

and advised them that Bushey, the regional operations vice president, had

authorized an extension until September for the repayment of travel

funds. 173 When the accounting department contacted Bushey for verification, he said that he had not authorized an extension. 174 Bushey and

Perdue met to discuss the advance on July 31, 1989. 175 Perdue denied

telling the accounting office that an extension had been authorized. 176 He

told Bushey that he had called the accounting office to tell them that he was

162. /d. at 408.

163. /d. at 407 (citing Moore v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 856 F.2d 488. 492 (2d Cir. 1988)).

164. /d. at 408.

165. 986 F.2d 970 (5th Cir. 1993).

166. /d. at 980.

167. 7 F.3d 1251. 1255 (5th Cir. Dec. 1993).

168. /d. at 1252.

169. /d.

170. /d.

171. /d. at 1252-53.

172. /d. at 1253.

173. /d.

174. /d.

175.

/d.

176. /d.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 594 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

595

unable to obtain an extension. 177 Bushey, no longer believing that Perdue

was trustworthy, terminated Perdue. 178

Perdue requested severance benefits. 179 BKC denied benefits because

the termination was not the result of a reduction in force or a job elimination program. 180 Perdue sued, alleging, among other things, that BKC

violated section 510 of ERISA by inducing him to accept the Franchise

Operations Manager position and then terminating him under the pretext of

just cause. 181 More specifically, Perdue alleged "that the misunderstanding

surrounding the travel advance provided the pretext for terminating Perdue's

employment ,,182 The district court refused "to consider [the] 'suspect'

circumstances surrounding his termination," and Perdue appealed. 183

The Fifth Circuit rejected Perdue's claim. l84 The court noted that

section 510 of ERISA "is concerned with acts taken against employees to

prevent rights from ripening. The prohibitions under the statute do not

extend per se to an employer who retains an employee so as to avoid

payment of severance benefits under an ERISA plan.' ,185

The court held that under ERISA section 510, a plaintiff is "required

to demonstrate that the employer discharged the claimant 'with the specific

intent of interfering with ... ERISA benefits." ,186 The court held that

BKC did not violate ERISA section 510 for two reasons. First, Perdue

offered no evidence that Bushey either induced Perdue to accept the other

position or terminated his employment "with the specific intent of

interfering with Perdue's attainment of rights under the Program.,,187

Second, at the time that Perdue was terminated, he no longer had any rights

under the Severance Program because he had accepted another position with

BKC. 188

177. [d.

178. [d.

179. [d.

180. [d.

181. [d.

182. [d.

183. [d.

184. [d.

185. [d.

186. [d.

at 1255.

at 1255 n.lI.

at 1255.

(citations omitted).

(citing Simmons v. Willcox. 911 F.2d 1077. 1081-82 (5th Cir. 1990); Clark v.

Resistoflex Co.• 854 F.2d 762. 770 (5th Cir. 1988)).

187. Perdue. 7 F.3d at 1255.

188.

[d.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 595 1995

596

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26:579

VIII. RULE #7: ONLY PARTICIPANTS, BENEFICIARIES, AND FIDUCIARIES,

BUT NOT INTENDED BENEFICIARIES, HAVE STANDING TO SUE UNDER

ERISA

Section 502 of ERISA grants participants, beneficiaries, fiduciaries, and

the Department of Labor standing to sue to redress a violation of ERISA.189

Participants,190 beneficiaries,191 and fiduciaries l92 are carefully defined

in ERISA and are identified as possible plaintiffs. The Fifth Circuit has

been reluctant to expand section 502 beyond this list of enumerated

plaintiffs.

In Coleman v. Champion International Corp.,193 the Fifth Circuit held

that a self-professed "intended beneficiary" (Coleman) did not have

standing to sue his father's (Charlie Coleman) pension fund to change the

type of retirement benefit his father was scheduled to receive at retirement. 194 Charlie Coleman reached age 55, early retirement age under the

plan, in July of 1986. 195 Charlie Coleman died the following March. 196

At the time of his death, Charlie Coleman was divorced. 197 He had not

remarried. 198 He was no longer employed by Champion International and

was entitled at any time to elect to start receiving his pension.199 Under

the plan, he could elect various optional forms of payments such as a tenyear certain, which would guarantee that he would receive benefits for his

lifetime.2oo However, if he died before ten years had elapsed, the payment

for the remaining years would be paid to a designated beneficiary.201

189. 29 U.S.C. § 1132(a)(I)-(5) (1988 & Supp. V 1993).

190. ERISA section 3(7) defines a participant as an "employee or former employee of an

employer, or any member or former member of an employee organization, who is or may become

eligible to receive a benefit of any type from an employee benefit plan which covers employees of such

employer or members of such organization, or whose beneficiaries may be eligible to receive any such

benefiL" 29 U.S.C. § 1002(7) (1988).

191. ERISA section 3(8) defines a beneficiary as "a person designated by a participant. or by

the terms of an employee benefit plan, who is or may become entitled to a benefit thereunder." 29

U.S.C. § 1002(8) (1988).

192. Under ERISA section 3(21), "a person is a fiduciary with respect to a plan to the extent (i)

he exercises any discretionary authority or discretionary control respecting management of such plan or

exercises any authority or control respecting management or disposition of its assets, (ii) he renders

investment advice for a fee or ... other property of such plan, or has any authority or responsibility to

do so, or (iii) he has any discretionary authority or discretionary responsibility in the achninistration of

such plan." 29 U.S.C. § lOO2(21)(A) (1988).

193. 992 F.2d 530 (5th Cir. June 1993).

194. ld. at 534.

195. ld. at 532.

196. ld.

197. ld..

198. ld.

199. ld.

200. ld.

201. ld.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 596 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

597

Charlie Coleman did not elect any optional form of payment, such as a tenyear certain, and he did not designate a beneficiary to receive benefits under

an optional form of payment. 202 Instead, he would receive a lifetime

annuity by default, with payments to begin once he retired. 203

The pension plan provided that if an unmarried terminated vested

participant, such as Charlie Coleman, died before he started receiving

benefits, the plan would pay no pension benefits.204 When Charlie

Coleman died, no benefits were paid, and his son sued to recover his

father's benefits?05

The court noted that the son clearly was not a participant or fiduciary

as defined by ERISA. 206 Coleman's only chance to establish standing

would be if he could prove he was a beneficiary under ERISA. 207 ERISA

section 3(8) defines "beneficiary" as "a person designated by a participant,

or by the terms of any employee benefit plan, who is or may become

entitled to a benefit thereunder.' ,208 Coleman did not satisfy this defInition because his father had not designated him as a beneficiary and the plan

did not name him as a beneficiary.209 Coleman argued that if the plan had

advised his father that his pension benefits would be forfeited unless he

selected an optional form of benefit, Charlie Coleman would have designated his son as his beneficiary.210 The court described this argument as

"speculative at best. "211 The court said: "[W]e do not agree that the

mere possibility that one could potentially have been named beneficiary is

sufficient to confer status under" section 502. 212

The plan defmed "beneficiary" as "anyone or more of the persons

comprising the group consisting of the participant's spouse, the participant's

descendants, the participant's parents or the participant's heirs at law ... of

. . . the estate of such deceased participant. . . .' ,213 The court rejected

Coleman's argument that because he was "Charlie Coleman's descendant,

heir at law, and the representative of Charlie Coleman's estate," he was a

beneficiary' under section 502. 214 The court explained that under the plan,

a Retirement Committee could designate a beneficiary from the group of

possible beneficiaries only if at the time of the participant's death, death

202.

203.

204.

205.

206.

2CY7.

208.

209.

210.

211.

212.

213.

214.

Jd.

Jd.

Jd.

Jd.

Jd. at 533.

Jd.

29 U.S.C. § 1002(8) (1988).

Coleman, 992 F.2d at 533.

Jd. at 533 n.6.

Jd.

Jd.

Jd. at 533.

Jd.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 597 1995

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

598

[Vol. 26:579

benefits were payable and the participant had failed to elect an alternate

payment option and had failed to name a beneficiary.2lS However,

because no benefits were payable at the time of Charlie Coleman's death,

the Retirement Committee was not authorized to name a beneficiary from

the liSt.216 Therefore, Coleman was not a beneficiary as defined by

ERISA and had no standing to sue,217

The court refused to expand the section 502 list of enumerated

plaintiffs, citing its previous holding that •• [w]here Congress has defined the

parties who may bring a civil action founded on ERISA, we are loathe to

ignore the legislature's specificity. Moreover, our previous decisions have

hewed to a literal construction of [section 502(a)]. ,,218 The court held that

"[a]bsent clear Congressional expression that non-enumerated parties such

as the appellant have standing to sue under ERISA, we decline to confer

such standing.' ,219

The court distinguished Christopher v. Mobil Oil COrp.,220 where the

court "restored ERISA standing to individuals who once had standing but

were divested of that standing because of the ERISA violations of their

employer, ,,221 In Christopher, a group of employees alleged that their

employer had wrongfully induced them to retire and that but for this

inducement they would have remirined participants and would have retained

standing to sue?22 The court noted in Coleman that "Coleman never had

standing to sue under ERISA since he was neither a plan participant nor a

beneficiary. ,,223 Thus, Christopher was not controlling. 224

215.

216.

217.

218.

Id.

Id. at 534.

Id.

Id. (citing Jamail. Inc. v. Ca!penters Dist. Council of Houston Pension & Welfare Trosts,

954 F.2d 299,302 (5th Cir. 1992); Hennann Hosp. v. MEBA Medical & Benefits Plan. 845 F.2d 1286,

1289 (5th Cir. 1988». In Yancy v. American PetrojifID, Inc., the court refused to grant standing to a

plaintiff who did not meet the statutory definition of "participant.' , 768 F.2d 7m, 708 (5th Cir. 1985);

see also Joseph v. New Orleans Elec. Pension & Retirement Plan, 754 F.2d 628,630 (5th Cir.) (holding

that plaintiffs lacked standing because they were not "participants" within the meaning of ERISA), cert.

denied, 474 U.S. 1006 (1985).

219. Coleman, 992 F.2d at 534.

220. 950 F.2d 1209 (5th Cir.), cerl. denied, _ U.S. --J 113 S. Ct. 68, 121 1.. Ed. 2d 35 (1992).

221. Coleman, 992 F.2d at 535.

222. Id. In Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. v. Bruch, the Supreme Court held that the tenn

"participant" in section 502 referred to "fonner employees who 'have ... a reasonable expectation of

retuming to covered employment' or who have a 'colorable claim' to vested benefits." 489 U.S. 101,

118 (1989). In Christopher, the Fifth Circuit stated that "it would seem ... logical to say that but for

the employer's amduct alleged to be in violatioo of ERISA, the employee would be a current employee

with a reasonable expectation of receiving benefits, and the employer should not be able through its own

malfeasance to defeat the employee's standing." 950 F.2d at 1221.

223. Coleman, 992 F.2d at 535.

224. Id.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 598 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

599

IX. RULE #8: UNDER MOST PLANS, THE PLAN ADMINISTRATOR WILL

HAVB DISCRETIONARY AUTHORITY TO CONSTRUE THE TERMS OF THE

PLAN, AND THEREFORE, THE STANDARD OF REVIEW WILL BE ABUSE OF

DISCRETION

.

In Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. v. Bruch,22S the Supreme Court

articulated the standard of review for a denial of employee benefits:

[A] denial of benefits challenged under § [502](a)(1)(B) is to be reviewed

under a de novo standard unless the benefit plan gives the administrator

or fiduciary discretionary authority to detennine eligibility for benefits or

to construe the tenns of the plan. . . . Of course, if a benefit plan gives

discretion to an administrator or fiduciary who is operating under a

conflict of interest, that conflict must be weighed as a "facto[r] in

detennining whether there is an abuse of discretion." 226

To avoid the uncertainty and expenses involved in de novo review, most

plans give the plan administrator discretionary authority to construe the

plan's terms.

The Fifth Circuit consistently applies a two-part test to determine if a

plan administrator has abused his or her discretion.227 First, the court

determines whether the administrator's decision was "legally correct...228

To determine if the decision was legally correct, the court considers three

factors: (1) whether the plan administrator has uniformly construed the

plan; (2) whether the administrator's interpretation of the plan is consistent

with a fair reading of the plan; and (3) whether the administrator's

interpretation results in any unanticipated costs.229

If the court determines that the administrator's interpretation of the plan

is legally incorrect, the court must then decide whether the administrator

abused its discretion. no Under the second step of the two-part test, the

court considers the following factors in determining if the administrator

abused its discretion: "(1) whether the [administrator's] interpretation is

internally consistent with the remainder of the plan; (2) whether the

[administrator's] interpretation comports with any relevant regulations

formulated by appropriate administrative agencies; (3) whether the factual

225.

489 U.s. 101 (1989).

226. Id. at 115.

227. The Fifth Cirroit has held that this two-part test is not required in every case. See Duhon

v. Texaco. Inc.• 15 F.3d 1302. 1306 (5th Cir. Feb. 1994). For example, in Duhon, the administrator

clearly did not abuse his discretion; thus, the two-part analysis was unnecessary. Id. at 1307 n.7.

228. Jones v. Sonat Inc. Master Employee Benefits Plan Admin. Comm.• 997 F.2d 113 (5th Cir.

Aug. 1993).

229. Id. at 115; see Wildbur v. ARCO Oem. Co., 974 F.2d 631, 637-38 (5th Cir. 1992); Jordan

v. Cameron Iron Works, Inc., 900 F.2d 53, 56 (5th Cir.). cert. denied. 498 U.S. 939 (1990).

230. SOMt Inc.• 997 F.2d at 116.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 599 1995

600

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26:579

background supports the [administrator's] detennination; and (4) any

inferences of lack of good faith on the [administrator's] part .. 231

Where a potential conflict of interest exists between the plan and the

participant, the court will scrutinize the decision more carefully: a review

will be "more penetrating the greater ... the suspicion of partiality, [and]

less penetrating the smaller that suspicion.' ,232

Duhon v. Texaco, Inc. 233 presented the Fifth Circuit with "a rather

typical question pertaining to ERISA benefits:" a claim that benefits were

improperly denied. 234 Clifford Duhon was employed by Texaco Trading

and Transportation, Inc. until he became disabled. 235 He began receiving

benefits under Texaco's disability plan.236 Under the tenns of the plan,

Duhon would receive benefits for the first twenty-four months following his

separation from work if he was unable to perfonn the nonnal duties of his

regular job or a comparable one.237 After twenty-four months, disability

payments would cease if Duhon was .. able to perfonn any job for which he

[was, or had become,] qualified by training, education, or experience.,,238

After twenty-four months, Duhon was evaluated by three doctors to

detelIDine whether his disability benefits should continue. 239 Duhon's

family doctor concluded that Duhon was pelIDanently disabled from working

as a truck driver. 240 Texaco's doctor of choice agreed that Duhon was

pennanently disabled and that Duhon should not drive trucks or lift heavy

objects.241 The third doctor, an orthopedist selected by Texaco, concluded

that Duhon had degenerative lumbar disc disease and that Duhon could not

"squat, stoop, bend, or lift more than twenty-five pounds... 242 The

orthopedist agreed that Duhon could not wort as a truck driver but said that

Duhon could do "sedentary to light wort... 243

Texaco's plan administrator and chief medical officer reviewed

Duhon's medical records and decided that Duhon was no longer eligible for

disability benefits. 244 Duhon's appeal, challenging the denial of benefits,

231.

232.

denied. 493

233.

234.

235.

236.

237.

238.

239.

240.

241.

242.

243.

244.

Jd.; see Wildbur. 974 F.2d at 638.

Lowry v. Bankers Life & Casualty Retirement Plan. 871 F.2d 522. 525 n.6 (5th Cir.). cerro

U.S. 852 (1989).

15 F.3d 1302 (5th Cir. Feb. 1994).

Jd. at 1304.

Jd.

Jd.

Jd.

Jd.

Jd.

Jd.

Jd.

Jd.

Jd.

Jd.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 600 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

601

was denied. 245 Duhon then sued Texaco and the plan administrator. 246

The trial court ordered Texaco to continue paying the disability benefits.247

Texaco appealed. 24s

Because the plan granted discretionary authority to the Texaco plan

administrator,249 the Fifth Circuit held that the administrator's decision was

subject to review under the abuse of discretion standard.250 The court

declined to follow the elaborate two-prong test adopted in Wildbur v. ARCO

Chemical CO.,251 stating that the test was not required in a case such as

Duhon's where the administrator clearly did not abuse his discretion. 252

The court rejected Duhon's argument that the administrator abused his

discretion by interpreting the plan language "any job for which he ... is or

may become qualified" to include any job that required only "sedentary to

light work" for which Duhon was otherwise qualified. 253 Duhon argued

that no evidence had been presented that "he [could] actually perfonn any

identifiable job.,,254 The court stated that:

It was not an abuse of discretion for the pIan administrator to conclude

that a sixty-five year old man with a high school diploma and plenty of

experience in the work-a-day world, although unable to squat, stoop, bend,

or lift more than twenty-five pounds, would be able to perform the

functions of some identifiable job. Indeed, to fmd otherwise would be

blindly and deliberately to ignore a common-and uncontested-truth:

people in their sixties and seventies who have similar physical and job

limitations ... are employed and employable throughout the workplace

today.2.5S

Next, the court considered whether the plan administrator abused his

discretion by denying benefits without obtaining the expert testimony of a

vocational rehabilitation expert to detennine if Duhon was capable of

perfonning other work. 256 The court refused to burden plan administrators

with a rule that would require them to consider vocational rehabilitation

245. Id.

246. Id.

247. The Fifth Circuit held that the trial court's award of disability benefits was emmeous. Id.

at 1309 n.7. The trial court should have remanded "the case to the plan administrator with instructions

to take additional evidence." Id.

248. Id.

249. The plan stated that "[t]he decisions of the Plan Administrator shall be final and conclusive

with respect to every question which may arise relating to either the interpretation or administration of

this Plan." Id. at 1305.

250.

Id.

251.

974 F.2d 631 (5th Cir. 1992).

Duhon, 15 F.3d at 1307.

252.

253. Id.

254. Id.

255. Id. at 1308.

256. Id.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 601 1995

602

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26:579

evidence to avoid an abuse of discretion charge.2S7 Instead, the court

determined that a case-by-case examination should be conducted to

determine whether a plan administrator abused its discretion by failing to

obtain the opinion of a vocational rehabilitation expert.2S8

The court concluded that in Duhon's case the plan administrator did not

abuse its discretion by failing to obtain the opinion of a vocational rehabilitation expert. 2S9 The court noted that "[g]iven ... [the] undemanding [plan]

language and the medical evidence in this case, the plan administrator could

competently determine disability without vocational testimony.' '260

Judge Johnson dissented. 261 He criticized the majority for avoiding

the real issue: Whether the plan administrator was required to ·specifically

determine if Duhon was qualified or could become qualified to perform a

job.262 Judge Johnson also criticized the majority for not analyzing the case

under the Wildbur two-step test. 263 He noted that the "application of the

two-step process in plan-interpretation cases is mandatory.' ,264 Judge

Johnson argued that Texaco had failed to meet its burden of proving that

Duhon "[was, or had become,] qualified [to perform a job] by training,

education. or experience.' ,265 Applying the first part of the two-step test,

Judge Johnson concluded that Texaco's deletion of this qualification

requirement was" anything but a •fair reading' of the plan. ,,266 Specifically,

Judge Johnson explained that Texaco's interpretation of the plan was

"anything but reasonable," as it ignored the plan's requirement that the

participant must either be capable of performing a job or have the ability to

become qualified to perform a job.267 Judge Johnson noted:

[W]hile it is true that Mr. Duhon is a high school graduate, the fact of the

matter is that many moons have passed since his graduation in 1947.

Nothing in the record reveals that Mr. Duhon ever used or honed any of

the skills he gained in school - whether reading, writing, or otherwise. 268

Therefore, Judge Johnson disagreed with the majority's conclusion that the

administrator did not abuse his discretion. 269

257.

258.

259.

260.

[d. at 1309.

[d.

[d.

[d.

261. [d. at 1310 (Johnson., J., dissenting).

262. [d.

263. [d. at 1310-11.

264.

265.

266.

267.

268.

[d. at 1310.

[d. at 1311.

[d.

See id. at 1312.

[d. at 1313.

269. [d.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 602 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

603

Under Firestone, if the plan does not give the administrator discretionary

authority, the court must review the administrator's decision de novo. 270

In Ramsey v. Colonial Life Insurance Co. of America,271 the court reviewed

the administrator's denial of benefits de novo because the plan did not give

the administrator discretion. 272

William Ramsey, Jr. was paralyzed from the neck down. 273 He was a

dependent under his wife's medical plan. 274 After receiving coverage under

this plan for two and a half years, the insurer discontinued coverage.275

Ramsey sued.276

The court interpreted the policy to require the insurer to continue

Ramsey's medical coverage.277 The court noted that the plan language

was clear, but even if it was ambiguous, any ambiguity would be construed

in favor of the insured under the doctrine of contra proferentem.278 The

court reiterated that:

Any burden of uncertainty created by careless or inaccurate drafting of the

summary must be placed on those who do the drafting, and who are most

able to bear that burden, and not on the individual employee, who is

powerless to affect the drafting of the summary or the policy and ill

equipped to bear the fmandal hardship that might result from a misleading

or confusing document. 279

The court construed any ambiguities against the insurer and held that

Ramsey was entitled to continued medical coverage.280

X. RULE #9: FACTUAL DETERMINATIONS BY A PLAN ADMINISTRATOR

ARE REVIEWED FOR ABUSE OF DISCRETION REGARDLESS OF PLAN

LANGUAGE

In Southern Farm Bureau Life Insurance Co. v. Moore,281 the Fifth

Circuit noted that in Firestone, the Supreme Court did not address the

applicable standard for review of a factual determination made by a plan

270.

271.

272

Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. v. Broch, 489 U.S. 101. 115 (1989).

12 F.3d 472 (5th Cir. Jan. 1994).

[d. at 478.

[d. at 473.

273.

274. [d.

275. [d.

276. [d.

277.

[d. at 479.

278. [d.; see Hansen v. Continental Ins. Co.• 940 F.2d 971, 982 (5th Cir. 1991); cf. Wise v. El

Paso Natural Gas Co., 986 F.2d 929, 938 (5th Cir. 1993) (stating that rules of constNctiOll announced

in Hansen "mandate that we adopt the most pro-beneficiary interpretation' .), cert. denied, _ U.S._,

114 S. Ct. 196, 126 L. Ed. 2d 154 (1993).

279. Ramsey, 12 F.3d at 479 (quoting Hansen, 940 F.2d at 982).

280. [d.

281.

993 F.2d 98 (5th Cir. June 1993).

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 603 1995

604

TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26:579

administrator. 282 In Pierre v. Connecticut General Life Insurance CO.,283

the Fifth Circuit held that an administrator's factual detennination should be

reviewed for abuse of discretion. 284 Under ERISA, a plan administrator

is a fiduciary.28S As a fiduciary, the administrator "possesses inherent

discretion through a statutory grant of authority to control and manage the

operation of the plan.' ,286 This result avoids the potential problem of

courts "supplant[ing] plan administrators, through de novo review, as

resolvers of mundane and routine fact disputes.' ,287

Applying Pierre, the Fifth Circuit ruled in Moore that the district court

erred in reviewing de novo the plan administrator's factual detenninations. 288 Not only may the court consider "the evidence that was available to the plan administrator" in evaluating the administrator's factual

detenninations, but the court also may consider additional evidence that was

not available to the administrator in reviewing the plan administrator's

interpretation of the plan. 289

The court looked to Texas law to detennine whether the plan administrator's refusal to pay accidental death benefits to Mrs. Moore was

proper.290 The plan excluded coverage for death that resulted from or was

contributed to by a disease or infinnity of the body.291 Southern Farm

Bureau denied benefits to Mrs. Moore, claiming that her husband's death in

an automobile wreck was caused by loss of consciousness triggered by a

brain tumor. 292

The court held that the administrator did not abuse his discretion when

he detennined, on the basis of three medical reports, the autopsy report, a

newspaper article, and the death certification, that the brain tumor, a bodily

disease, caused or contributed to Mr. Moore's death. 293 The court held

282. /d. at 100.

283. 932 F.2d 1552 (5th Cir.). cert. denied, _ U.S. _ ' 112 S. a. 453. 116 L. Ed. 2d 470

(1991).

284. /d. at 1562.

285. 29 C.F.R. § 2509.75-8(0-3) (1993).

286. Moore, 993 F.2d at 101.

287. /d.

288. /d. The trial court applied a de novo standard of review because the administrator did not

notify the claimant that the claim had been denied. /d. The Fifth Circuit noted that Department of Labor

regulations provide that if a claim is not denied, it will be deemed denied. /d. (referring to 29 C.F.R. §

2560.503-1(h)(l),(4». The Fifth Circuit held that the standard is the same regardless of whether the

claim is actually denied or deemed denied. /d. The Fifth Circuit reviewed the administrator's factual

detennination under an arbitrary and capricious standard. /d.

289. /d. at 102. The court also noted that under Firestone, since the plan administrator apparently

did not have discretionary authority to interpret the plan, the plan administrator's interpretation of the

plan should be reviewed de novo. /d. at 101.

290. /d.

291. /d.

292 /d. at 100.

293. /d. at 103.

HeinOnline -- 26 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 604 1995

1995]

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS

605

that this evidence was sufficient to support the plan administrator's

detennination that the accident was a result of Mr. Moore's brain tumor.294

XI. RULE #10: ADVISORS WHO Do NOT HAVE AUTHORITY AND

CONTROL OVER PLAN ASSETS AND WHO Do NOT RENDER REGULAR

INVESTMENT ADVICE TO THE PLAN ARE NOT FIDUCIARIES

In Sch/oege/ v. Boswe//,295 the Fifth Circuit held that an insurance

agent who purchased life insurance on behalf of a pension plan was not a

fiduciary.296 In 1977, Boswell, an insurance agent, purchased two ordinary

life insurance policies insuring the life of a plan participant. 297 The plan

paid insurance commissions for ten years until the plan realized that the

insurance policies violated the Internal Revenue Code,298 which requires

death benefits to be •• incidental" to the primary purpose of providing

retirement benefits.299 The plan cashed in the insurance policies and sued

Boswell for breach of fiduciary duties under ERISA. 300

ERISA section 3(21)(A) provides that a person is a fiduciary with

respect to the plan:

to the extent (i) he exercises any discretionary authority or discretionary

control respecting management of such plan or exercises any authority or

control respecting management or disposition of its assets, (ii) he renders

investment advice for a fee or other compensation, direct or indirect, with

respect to any moneys or other property of such plan, or has any authority

or responsibility to do so, or (iii) he has any discretionary authority or

discretionary responsibility in the administration of such plan?01

The plan argued that Boswell had effective control over the plan's

investments because the trustee relied on Boswell's expertise and long-term

relationship with the plan in deciding to purchase the life insurance.302

294.

295.

(1993).

[d.

994 F.2d 266 (5th Cir. July), cert. denied, _