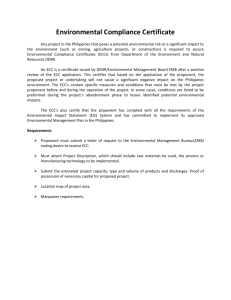

Chapter 2 2 Project Development

advertisement