Anf 1 anterior end of the main embryonic axis

advertisement

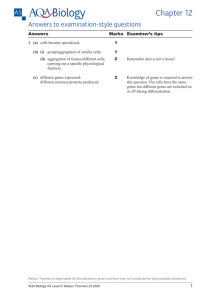

Gene 200 (1997) 25–34 Anf: a novel class of vertebrate homeobox genes expressed at the anterior end of the main embryonic axis1 Olga V. Kazanskaya a, Elena A. Severtzova a, K. Anukampa Barth b, Galina V. Ermakova a, Sergey A. Lukyanov a, Alex O. Benyumov c, Maria Pannese d, Edoardo Boncinelli d,e, Stephen W. Wilson b, Andrey G. Zaraisky a,* a Shemyakin and Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, Russian Academy of Sciences, ul. Miklukho-Maklaja 16/10, V-437 Moscow, 117871, Russia b Development Biology Research Centre, Randall Institute, King’s College, Drury Lane, London, WC2B 5RL, UK c Biological Faculty, Moscow State University, 117234 Vorobievi gori, Moscow, Russia d Istituto Scientifico HS Raffaele, Via Olgettina 60, 20132 Milan, Italy e Centro Infrastrutture Cellulari, CNR, Via Vanvitelli 32, 20129 Milano, Italy Received 26 January 1997; accepted 16 May 1997 Abstract Five novel genes homologous to the homeobox-containing genes Xanf-1 and Xanf-2 of Xenopus and Hesx-1/Rpx of mouse have been identified as a result of a PCR survey of cDNA in sturgeon, zebrafish, newt, chicken and human. Comparative analysis of the homeodomain primary structure of these genes revealed that they belong to a novel class of homeobox genes, which we name Anf. All genes of this class investigated so far have similar patterns of expression during early embryogenesis, characterized by maximal transcript levels being present at the anterior extremity of the main embryonic body axis. The data obtained also suggest that, despite considerable high structural divergence between their homeodomains, all known Anf genes may be orthologues, and thus represent one of the most quickly evolving classes of vertebrate homeobox genes. © 1997 Elsevier Science B.V. Keywords: Homeobox genes; Embryo; Forebrain patterning 1. Introduction Homeobox-containing genes play crucial roles in regional patterning and cell differentiation during development of multicellular organisms. Protein products of these genes act as specific transcription factors, binding with regulatory elements of target genes by means of a common conserved 60-aa motif, called the homeodo* Corresponding author: Tel: +7 (095) 3363622; Fax: +7 (095) 3306538; e-mail: zar@humgen.siobc.ras.ru 1 GeneBank accession numbers: U65433, U65436 and U82811. Abbreviations: aa, amino acid; Anf, class of homeobox-containing genes; Aanf, Danf, Ganf, Hanf, Panf, Xanf-1, Xanf-2, members of Anf class of genes in different species ; bp, base pair; en, engrailed; eve, even-skipped; msh, muscle segment homeobox gene; ftz, fushi tarazu; flh, floating head; Not, class of genes encoding negative transcription regulators; Otx, class of orthodenticle-related genes; PAX, class of pairedrelated genes; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; Prop.1, Prophet of Pit1 gene; Xotx2, Xenopus homologue of Otx2; zli, zona limitans intrathalamica. 0378-1119/97/$17.00 © 1997 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. PII S 03 7 8 -1 1 1 9 ( 9 7 ) 0 0 3 26 - 0 main [reviewed by Scott et al. (1989) and McGinnis and Krumlauf (1992)]. It is the primary structure of this motif that primarily determines DNA binding specificity of homeodomain-containing proteins both in vitro and in vivo [reviewed by Gehring et al. (1994)]. The homeobox gene family can be subdivided into about 30 classes of genes, each characterized by its own specific consensus sequence of the homeodomain ( Kappen et al., 1993). In the present study, we characterize a novel class of homeobox genes encoding a homeodomain consensus sharply different from those of other classes. The first member of this class, Xanf-1, was cloned in Xenopus laevis (Zaraisky et al., 1992). Xanf-1 homologues have since been identified in mouse, Hesx-1 ( Thomas et al., 1995) [this gene was also described as Rpx (Hermesz et al., 1996)], and in Xenopus, Xanf-2 (Mathers et al., 1995). Xanf-2 appears to be very similar to Xanf-1 and probably is a pseudo-allelic copy of it. Besides these genes, we now describe five novel homologues of Xanf1 in zebrafish (Danio rerio—Danf ), sturgeon (Acipenser 26 O.V. Kazanskaya et al. / Gene 200 (1997) 25–34 baeri—Aanf ), newt (Pleurodeles waltlii—Panf ), chick (Gallus gallus—Ganf ) and human (Homo sapiens— Hanf ). In all species investigated, these genes are expressed at the most anterior extremity of embryo in a very restricted time interval during gastrulation and neurulation; moreover, in the anterior neurectoderm (in Xenopus laevis, this region corresponds to the anterior neural fold ), they are expressed most intensively. Based upon the name of the first member of this class of genes (Xanf-1) and upon their expression patterns, we propose to name the family Anf genes. All data currently obtained indicate that Anfs could be involved in the early patterning of the most anterior region of the main embryonic body axis. 2. Materials and methods 2.1. Embryo manipulations Sturgeon (Acipenser baeri) and zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos were obtained by natural spawning or by artificial fertilization, and staged according to Detlaff and Ginsburg (1954) and Kimmel et al. (1995), respectively. Newt (Pleurodelis waltlii) embryos were collected by natural spawning and staged according to Gallien and Durocher (1957). Fertile white leghorn chicken (Gallus gallus) eggs were incubated at 38°C and staged according to Hamburger and Hamilton (1951). Tissue pieces were extirpated from embryos in appropriate physiological solutions using an eye-surgery microknife and a fused glass capillary. 2.2. Preparation of amplified cDNA samples Total RNA was purified using homogenization of tissue explants with guanidine isothiocyanate and phenol/chloroform extraction (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987). First cDNA strand synthesis and preparation of amplified cDNA, involving oligo dA-tailing of the first cDNA strand and subsequent PCR with T(13)-stretch containing primer (5∞CGCCAGTCGACCG( T ) ), were 13 performed exactly as described earlier (Lukyanov et al., 1995). First cDNA strand and amplified cDNA were purified from unincorporated dNTPs and the excess of primers using Wizard PCR Prep DNA Purification System (Promega). 2.3. Amplification of homeobox fragments from cDNA by PCR The following degenerated oligonucleotides were designed to amplify Anf homeobox fragments. For the RELSWYR motif: 5∞-AGAGAGARCTNAGYTGGTA; for the NS/CYPGID motif: 5∞-AAYTCA- TAYCCNGGTATWGAT; for the ESQFLI/M motif: 5∞-TATYAGRAAYTGQGAYTC; for the WFQNRR motif: 5∞-GNCGRTTYTGRAACCA; where N=A, G, C or T; Q=T or G; R=A or G; W=A or T; Y=C or T. PCR with previously amplified cDNA samples (see above) was performed using a thermostable DNA polymerase mixture of KlenTaq (AB Peptides, USA) and pfu (Stratagene) at a ratio of 150:1 U/U under the following conditions: two cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 46°C for 30 s, 72°C for 2 min, then 25–28 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min. In the case of human, the template for PCR reactions was phage DNA prepared from human undifferentiated teratocarcinoma NT2/D1 cDNA library (provided by Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine). In this case, an additional round of PCR (with one initial and one novel, ‘internal’, degenerate primer) was performed after a 1000-fold dilution of the PCR product that had been obtained in the first round. Purified PCR products were subcloned into pBluescribe KS vector (Stratagene, USA) and 20–30 colonies in each case were tested by PCR using ‘internal’ degenerate primers (that were not used in initial PCR) in combination with a primer specific for the pBluescribe KS vector. All positive clones were then sequenced using Promega ‘fmol’ sequencing kit. In some cases, positive clones were identified using hybridization of the filter replicas with a Xanf-1 derived probe in low stringency conditions. 2.4. Amplification of 5∞- and 3∞-ends of Anf cDNAs by RACE To obtain the remaining regions of Anf cDNAs, a technique based upon the theory of suppression-PCR was used (Lukyanov et al., 1995; Chenchik et al., 1996). In contrast with the previously published method, inverted terminal repeates were introduced into amplified cDNA samples (see above) not by a ligation procedure, but using 10 cycles of PCR with elongated T(13)-stretch containing primer ( ETP): 5∞-AGCACTCTCCAGCCTCTCACCGCAGTCGACCG ( T ) . 13 When this PCR was completed, the reaction mixture was diluted 1000 times (to avoid amplification with ETP in further rounds of PCR), and two rounds of PCR 25 cycles each (also interrupted by the 1000 times dilution) were performed with a pair of nested specific primers to the homeobox. These primers were successively combined in the first round of PCR with a primer representing the outer part of ETP (5∞-AGCACTCTCCAGCCTCTCACCGCA), and in the second round with ( T ) -stretch containing primer (see Section 2.2). 13 The following pairs of nested specific primers were used to amplify 3∞-ends of Anf cDNAs (for each species, the first primer is the one used at the first round of PCR); for sturgeon: 5∞-CCCAGGACGGCTTTCAGTG and 5∞-GCTCTAGAGTGGAGCCCAGATCGAGGT; O.V. Kazanskaya et al. / Gene 200 (1997) 25–34 for zebrafish: 5∞-AACAGCCTTCTCCAGTGT and 5∞-TCTAGATCAAGATATTAGAGAGTGTT; for newt: 5∞-AGCTGGTACCGAGGTCGGA and 5∞-TCTAGAGGCCGAGGACAGCCTTCAG; for chick: 5∞-AGGGGTAGAAGACCGAGAACT and 5∞-TCTAGACTGCTTTCACTAGAAACCAG. Pairs of nested specific primers used to obtain 5∞-ends of Anfs cDNAs were as follows; for sturgeon: 5∞-CATCCAGCTCCAGTTTGCAC and 5∞-AGAAGCTTAGGGTAGGGGTTCACTCT; for zebrafish: 5∞-ATAGTTCACTTGGAAAACAC and 5∞-GAAAGCTTCTAATATCTTGATCTGAAC; for newt: 5∞-CTCTCGAATGTCAATGCCG and 5∞-AGAAGCTTAATGTCAATGCCGGGATAC; for chick: 5∞-GGGATCTCTTCAGTTTTGC and 5∞-AGAAGCTTCGGTTCTGGAACCAGAT. The longest PCR bands (presumably representing the full-length 3∞ and 5∞-cDNA ends) were excized from the agarose gel and cloned into pBluescribe KS vector (Stratagene, USA) for further sequencing. In the case of Hanf, 3∞- and 5∞-cDNA ends were isolated by PCR from the phage DNA of teratocarcinoma cDNA library using primers specific to phage in combination with the following pairs of nested specific primers; for the 3∞ end: 5∞-CAAGAACTGCTTTTACTCAAAA and 5∞-GTGTTAGAAAATGTCTTTAG, for the 5∞ end: 5∞-CCTTTTCAGTTTTGCACG and 5∞-CTGGATTCTRTCTTCCTCTAG. To minimize the possibility of PCR mistakes, Anf cDNAs were finally sequenced using templates obtained by 30 cycles of PCR directly from the first cDNA stands or, in the case of human, from phage DNA, with the KlenTaq (AB Peptides, USA)/pfu (Stratagene) mixture (Barnes, 1994) and the following specific primers to the most 5∞ and 3∞-terminal regions of cDNAs (these primers were designed on the base of sequencing information obtained at previous steps); for sturgeon: 5∞-CAATATTTATTAAGCAATAAC and 5∞-AAATGCCAGGCTCGCAG; for zebrafish: 5∞-TCAGTTGGAGTTAAATTAAAGG and 5∞-ATTATTTATTTATATTTTGGCC; for newt: 5∞-GCTTCCGCCACGCGATC and 5∞-ACCATTAGAAAATGTTTTTATTC; for chick: 5∞-GGGTACCATCCATCAGCA and 5∞-GGAAAAGCTTCACTTTCTCCAC, for human: 5∞-GCTCTGTGCAGACCACGAGA and 5∞-TCTGTGTCTAGTACCCTGGT. The following conditions of PCR were used in all the experiments described above; denaturation: 94°C for 30 s; annealing at 56°C for 30 s; extension: 72°C for 2 min. Final sequences were deposited into GeneBank under accession numbers: U65433–U65436 and U82811. 2.5. Whole-mount in-situ hybridization Whole-mount in-situ hybridization on zebrafish was performed as described in Xu et al. (1994) and for other 27 species as described in (Harland, 1991), with digoxigenin-labelled probes and, in the case of Otx-2, with fluorescein-labelled probes. 3. Results and discussion 3.1. Isolation of Anf nucleotide sequences To isolate cDNAs of Xanf-1 homologues in sturgeon, zebrafish, newt and chick, we used a PCR-based strategy. To enrich initial samples of total cDNA with the required templates, they were obtained by a suppressionPCR technique, directly from individual pieces of anterior neurectoderm extirpated from embryos just after the end of gastrulation (Lukyanov et al., 1995; see also Materials and Methods). Anterior tissue at this stage was selected with the assumption that the place and the time of intensive expression of Xanf-1 homologues should be roughly the same in different species. Taking into account that in every case, the extirpated tissue piece (which presumably contained the majority of Anf expressing cells) was at least 20 times smaller than the whole embryo, one may suppose that cDNA samples obtained by this technique should be enriched with Anf templates by about 20 times in comparison with the total cDNA routinely prepared from the whole embryos. This strategy had an additional advantage because as total cDNA samples were obtained by PCR, it was not necessary to collect a large amount of embryonic polyA RNA for the first strand synthesis. In the next step, the homeobox fragments of Anf genes were obtained from the enriched cDNA samples by PCR with a set of degenerate primers corresponding to Anf specific conservative amino acid motifs (see Materials and Methods). This set allowed us to perform a PCR survey with four different pairs of primers and, in addition, easily to test the homeobox specificity of the PCR products. Interestingly, only one Anf class gene was identified for each of the species investigated, despite the fact that, in each case, several positive clones were analysed by sequencing. To obtain the remaining fragments of Anf cDNAs, we used the initial samples of total cDNA and a technique based on the principle of suppression-PCR (Siebert et al., 1995; Chenchik et al., 1996). The utility of this strategy allowed us quickly to isolate overlapping fragments representing Anf cDNA sequences of the following lengths; for Anf: 1091 bp; for Danf: 717 bp; for Panf: 929 bp. The sequences with the longest ORFs starting from the methionine codon were 174, 161 and 185 aa, respectively. For Ganf, overlapping fragments representing a sequence of 865 bp with the longest ORF of 184 aa were isolated. The obtained fragments of Ganf cDNA, however, do not contain the entire ORF. In the case of human, overlapping fragments representing a 28 O.V. Kazanskaya et al. / Gene 200 (1997) 25–34 Hanf cDNA sequence of 754 bp were isolated by the same PCR strategy, but using phage DNA of teratocarcinoma cDNA library as the template. The longest ORF of Hanf starting from methionine was 185 aa. 3.2. Primary protein structure Anf proteins vary in length from 161 (in zebrafish) to 187 amino acids (in Xenopus). The main feature of these proteins which permitted all Anf genes to be assigned to a distinct class is the much higher degree of identity revealed when their homeodomains are compared with each other (more than 75%), than with any homeodomain of other known classes ( less than 55%). Moreover, amino acid sequences of three regions that form secondary structures directly involved in protein–DNA interactions and thus determine functional specificity of the homeodomain (the N-terminal arm, the region near the start of a-helices 2 and a-helix 3/4), demonstrate the highest identity within the Anf class (Fig. 1A) and clear differences with analogous sequences of other homeodomains. The primary structure of helix 3/4 (the so-called recognition helix) plays the most important role in DNA sequence recognition (Gehring et al., 1994). Amino acid residues in the more variable positions of this helix (positions 1, 2, 5, 6 and 9) are expected to be more significant for control specificity of DNA binding than the conservative frame work amino acids (Scott et al., 1989; Gehring et al., 1994). The residue in the ninth position is the most critical among all variable amino acids for the formation of the homeodomain–DNA complex. Thus, in the bicoid protein, changing a lysine residue at the ninth position to glutamine or serine Fig. 1. (A) Comparison of amino acid sequences of known Anf homeodomains. All sequences are compared to the amino acid sequence of the Xanf-1 homeodomain (top). Dashes indicate sequence identities to Xanf-1. The residues that are absolutely conserved within each class are shown below as the consensus sequence (section 3.2.). (B) Table representing numbers of amino acid mismatches between different Anf homeodomains is shown in comparison with a similar table for Otx2 homeodomains. Note much higher mutual divergence of Anf homeodomains (section 3.3). O.V. Kazanskaya et al. / Gene 200 (1997) 25–34 allows the homeodomain to bind to DNA consensus sequences, which are normally recognized respectively by the Antennapedia or paired class homeodomains (Hanes and Brent, 1989). All known homeodomains of the Anf class have a glutamine residue at position 9 of the recognition helix (Fig. 1A). Therefore, theoretically, they should not bind DNA sequences recognized by the products of such homeobox genes as PAX, Otx and goosecoid. However, Anf proteins may recognize the same DNA motifs as Antennapedia, engrailed, msh and some other homeodomains. In contrast with members of the other homeobox families, Anf proteins demonstrate a specific set of amino acid residues in other variable positions of the recognition helix. Despite these amino acids being less critical for DNA binding, they are also suspected to be important for the affinity of the homeodomain to specific nucleotide sequences (Desplan et al., 1988; Scott et al., 1989; Gehring et al., 1994). In the case of Anf proteins, asparagine residues at the second position seem to be the most intriguing. As far as we know, this amino acid is present at this position in only two homeodomains from more than 300 described so far: in ceh-10 (Hawkins and McGhee, 1990) and Oct-4 (Scholer et al., 1990). Moreover, these two homeodomains belong to different classes ( Kappen et al., 1993), and it seems likely, therefore, that an asparagine residue at the second position represents an arbitrary variation only in these representatives of the two classes. By contrast, asparagine occupies the second position of the recognition helix in all known Anf homeodomains. Such a high conservation indicates an important role of asparagine at this position for Anf homeodomain functioning. Interestingly, a critical role for the amino acid residue at the second position in DNA binding has been demonstrated in Drosophila for the fushi tarazu (ftz) homeodomain (Furukubo-Tokunaga et al., 1992). Amino acid residues 1–7 of the N-terminal arm of the homeodomain interact with the minor groove of the DNA and also may influence the homeodomain binding specificity (Gibson et al., 1990; Lin and McGinnis, 1992). These residues form an entirely conserved sequence, GRRPRTA, in all known homeodomains of the Anf class ( Fig. 1a). This sequence is most similar to the N-terminal arm consensus sequences of the en, evenskipped (eve) and prd homeodomains, differing from en and eve by the first and the second and from the prd by the first, second and third amino acid residues. Amino acids located in the third putative DNAinteracting region (the loop between a-helices 1 and 2 and in the N-terminal part of helix 2) also form a common sequence, PGID (Fig. 1A), which appears to be specific exclusively for Anf class homeodomains. As has been shown in experiments with the ftz homeodomain, a residue at position 28 is the most important for DNA binding among all other variable residues of this 29 region ( Furukubo-Tokunaga et al., 1992). This is an isoleucine residue in Anf proteins. This amino acid in this position is quite rare and, besides the Anf class, is only present in some homeodomains of the paired class. All Anf homeodomains are flanked by specific conservative sequences: K/RRE/A,D,TL/QN/SWY from the aminoterminus and RESQFLM/IV/AK/R from the carboxyterminus. These sequences have no homologues among other known flanking sequences that have been previously described for classes of homeodomains. Along with the described homologous regions, there are two further conservative motifs: P/HH/YRPW and FT/SID/EH/SILGL near the N-terminuses of Anf proteins. The last sequence has some similarity with the octapeptide of paired-type proteins: HSIAGILG (Burri et al., 1989). Despite this similarity, Anf genes seem not to be tightly related with paired class genes. Indeed, Anf homeodomains do not demonstrate any exceptional homology with paired class homeodomains (not more than 54%). In addition none of the Anf proteins contains other important feature of many paired-type proteins— the paired domain. Outside the regions mentioned above, Anf proteins have a low homology with each other. The only exception is the products of two genes identified in Xenopus laevis, Xanf-1 and Xanf-2, demonstrating an unusually high identity of about 90% over the whole sequence. Interestingly, the same degree of identity (90%) is revealed when the translated regions of the cDNAs of these two genes are compared. This fact clearly indicates that the duplication that generated Xanf-1 and Xanf-2 was a quite recent event, which probably happened only in the evolutionary branch leading to Xenopus. Indeed, genes that diverged so long ago that now they are present in different classes of Vertebrates (for example, homeobox genes otx-1 and otx-2, en-1 and en-2) usually demonstrate a considerably higher degree of identity at the protein level than at the nucleotide level. Bearing in mind the well-known phenomenon of duplication of the Xenopus genome, one can hypothesize that these two genes represent a pair of pseudo-allelic genes present only in this, or maybe also in other species of this Amphibian genus (Richter et al., 1990). Indeed, analogues pairs of pseudo alleles have been revealed for some other Xenopus homeobox genes (Fritz et al., 1989). 3.3. Unusual evolutionary non-stability of the Anf homeodomain primary structure As the Anf homeodomains from different species show a considerable divergence from each other and fail to obviously subdivide into different sub-classes ( Fig. 1B), it is possible that the genes coding for these homeodomains are all non-orthologous homologues, and in each species, there may exist as-yet unknown Anf 30 O.V. Kazanskaya et al. / Gene 200 (1997) 25–34 O.V. Kazanskaya et al. / Gene 200 (1997) 25–34 genes, encoding homeoproteins with homeodomains less diverged from known Anf genes in other species. Although we cannot completely discount this possibility, it seems unlikely that we isolated five non-orthologous genes (Xanf-1, Danf, Panf, Ganf and Aanf ) from cDNA samples derived from similar embryonic stages and tissues. If all five genes are non-orthologous, then we would expect at least four unknown Anf genes in each of the species studied, all of them expressed at the same time and in the same tissues. If we assume that in each of the species, transcripts of all five genes are present in equal concentrations in the tissues studied, then we can make a rough calculation as to the likelihood that we isolated non-orthologous genes in each species. The probability of finding only non-orthologous genes during screening of these cDNA samples is: P=p · p · p · p · p , where p is the probability of find1 2 3 4 5 1 ing only one type of sequence in the first species; p —the probability of finding another, but also only 2 one, type of sequence in the second species, etc. If, for instance, only two independent clones were analysed for each of the species studied (in reality, we analysed more than two), then: p =5/52; p =4/52; p =3/52; 1 2 3 p =2/52; p =1/52. Thus, P=5!/510, or approximately 4 5 0.00001. Clearly, it appears to be very unlikely that we would isolate different non-orthologous Anf genes in 31 each species, and so we can conclude that at least some of these five genes are likely to be true orthologues. If only some of the genes that we isolated are orthologues, then we would expect to see a sharp difference in the number of mismatches when comparing homeodomains of the orthologous group with nonorthologous homologous. Instead, we find that all five homeodomains considered above show approximately similar degrees of divergence from each other ( Fig. 1B). Given these considerations, and the similarities in expression described below, we feel that it is probable that all five genes are indeed orthologues. However, we should caution that our analysis cannot exclude the possibility that several very homologous Anf genes may present in the same genome (for example, Xanf-1 and Xanf-2). In such cases, it is probably not feasible to assign orthology to one of the pair and not the other. Also, we cannot exclude that there may still be unknown Anf genes in the species studied, which are expressed at other times and in other tissues, or that there are other more divergent Anf genes that would not have been amplified using our primer sets. Given the possibility that all known Anf genes are orthologues, the unusually high degree of divergence between their homeodomains is noteworthy. Indeed, homeodomains of all other known homeobox-containing orthologues in Vertebrates listed in Stein et al. (1996) Fig. 2. Whole-mount in-situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labelled probes to Danf (in zebrafish), Xanf-1 and Xotx2 (in Xenopus) and Ganf (in chick) (section 3.4). (A–D). Danf expression at successive stages of zebrafish development. (A) At 70% of epiboly, Danf is expressed dorsal to the embryonic shield. The embryo is shown from the left side, animal pole up. (B) At the 80% epiboly, the expression domain in the prospective neuroectoderm has a trapezium-like shape. The embryo is shown from the animal pole, dorsal side up. (C ) At the end of epiboly, the expression of Danf is restricted to the crescent-shape domain at the anterior margin of the neural plate (black arrow) to a more weak, ‘M’-shaped, posterior domain (white arrow). (D) By the eight-somites stage, the expression of Danf is restricted to dorsal telencephalon. ( E–L) The expression of Xanf1 and Xotx2 in Xenopus. ( E ) At the early midgastrula stage (stage 11), transcripts of Xanf-1 are still faintly present in cells of the leading edge of the gastrulating mesoendoderm (cells of the presumptive prechordal plate and foregut endoderm)—black arrow. At the same time, a more pronounced expression (white arrow) is seen in adjacent cells of the deep layer of the anterior neurectoderm. (F ) At the beginning of neurulation (stage 13), the Xanf-1 expression domain in the anterior neurectoderm has a trapezium-like shape. The anterior limit of the presumptive neural plate is marked by triangles. (G) At the mid-neurula (stage 15), intensive expression of Xanf-1 is restricted to two domains at the anterior and posterior borders of the initial expression territory. The anterior, more pronounced expression domain coincides with the anterior margin of the neural plate and has a stripe of higher intensity bordering the medial anterior ridge from the anterior side (white triangle). The posterior, weaker domain appears to surround the anterior tip of the prospective floorplate (black arrow), and comes into contact with the anterior domain by lateral strips of weaker expression (black triangles). (H ) During the second half of neurulation, in parallel to neural tube closure, the expression of Xanf-1 is progressively down-regulated in its posterior domain (triangles). (I ) By the end of neurulation (stage 21), Xanf-1 expression appears to be restricted exclusively to the medial part of the anterior domain corresponding to the anterior pituitary anlage (triangle). (J ) At the early neurula stage (stage 13), the homeobox-containing gene Xotx2 is expressed in a wide area, which entirely includes the Xanf-1 expression domain. The posterior limit of this territory corresponds to the presumptive midbrain–hindbrain boundary (triangles), and the anterior limit (arrowheads) is in the non-neural ectoderm, surrounding the anterior margin of the neural plate. ( K ) At the midneurula (stage 15), a transverse domain of intensive expression is segregated in the posterior part of the Xotx2 expression territory. The anterior limit of this domain (triangles) corresponds to the prospective zona limitans intrathalamica (zli). (L) Double-labelling in-situ hybrydization with Xanf-1 (blue) and Xotx2 ( light brown) probes demonstrates that at stage 15, the posterior domain of Xanf-1 expression appears to be located just anterior to the domain of intensive Xotx2 expression [compare with (G) and ( K )]. Triangles mark the border of the whole Xotx2 expression territory. (M–P) Expression of Ganf in chick. In all pictures, except (P), embryos are shown from the dorsal side, anterior end to the top. (M ) In chick, Ganf expression can be first detected in the anterior neurectoderm at HH5 stage. Note that at this stage, the expression is present in the prechordal plate, which is seen as a spot through the neurectoderm (arrow). Triangle indicates Hensen’s node. (N ) At the HH5–6 stage, Ganf is intensively expressed in a broad territory of neural ectoderm just anterior to the rostral tip of the floor plate. (O) At the head fold stage (stage HH8-, three somites) the expression of Ganf is localized in cells of the anterior neural fold with a local maximum of intensity in its medial part. Two symmetrical weaker local spots of expression are seen in the lateral folds (triangles). (P) At the eight-somite stage, very weak Ganf expression is seen as two symmetrical strips in dorsal telencephalon (arrow). The embryo is shown from the ventral side. Scale bar is 100 mm for A–L and 500 mm for M–P. 32 O.V. Kazanskaya et al. / Gene 200 (1997) 25–34 appear to diverge less than 5% (with the only exception of NOT2 class, in which divergence achieves 10%), even if such distant organisms as fishes and mammals are compared (see, as an example, the table of the numbers of mismatches between different Otx2 homeodomains in Fig. 1B). Conversely, in the case of Anf proteins, the divergence is already 5% between mammalian species (mouse and man) and more than 20% if mammals and fishes are compared. Interestingly, all the changes in Anf homeodomains appear to be restricted exclusively to regions that presumably do not contact DNA. In this respect, one can speculate that in different species, Anf may bind the same DNA motifs, but if the Anf class of homeoproteins has less protein–protein interactions than other classes of homeodomains, they could escape the strong stabilizing pressure of natural selection in regions not involved in DNA binding. Alternatively, the amino acid substitutions in more divergent regions may not be of a neutral character, but could be stipulated by some type of co-evolution of Anf proteins and their co-factors. 3.4. Embryonic expression and possible functions A specific feature of all known Anf genes is their expression within the most anterior region of the embryonic body axis during gastrulation and neurulation. The expression has a transient character, starting early during gastrulation, reaching maximal intensity around gastrulation–neurulation transition and then gradually decreasing (Fig. 2). In mice and frogs, early Anf expression has previously been shown to occur both in ectoderm and in mesendodermal cells, primarily of the prechordal plate [Fig. 2E; see also Mathers et al. (1995), Zaraisky et al. (1995), Hermesz et al. (1996) and Thomas and Beddington (1996)]. It is also possible that comparable mesendodermal tissues weakly express Anf in chicks ( Fig. 2M ) and in fish, although the strong ectodermal expression and very thin hypoblast layer in fish makes this difficult to ascertain. In ectoderm, Anfs are initially (from the midgastrula stage) expressed within a broad territory of the anterior neural plate (Fig. 2B, F, N ). This territory appears to be localized entirely within the expression domain of another early expressing head marker, the homeobox gene Xotx2 (Fig. 2G). The latter gene is expressed at this stage in a wide area, which includes the neural plate anterior to the presumptive midbrain–hindbrain boundary, along with a fragment of non-neural ectoderm, surrounding the anterior margin of the neural plate. As neurulation proceeds, the posterior margin of the initial trapezium-shaped territory of the Anf expression domain becomes increasingly curved, possibly because of morphogenetic movements associated with floorplate extension in the midline of the neural plate (Fig. 2C, G, N, O). At the same time, at least in zebrafish and Xenopus, intense expression of Anf becomes restricted to two domains just at the anterior and posterior borders of the initial expression territory. The anterior, more pronounced expression domain coincides with the anterior margin of the neural plate, whereas the posterior, weaker domain appears to surround the anterior tip of the prospective floorplate (Fig. 2C, G). According to neural plate fate maps in Xenopus and chick, the anterior domain of Anf expression coincides in its medial part with the location of pituitary anlage and in its lateral parts with the presumptive dorsal telencephalon and anterior part of dorsal diencephalon (Couly and LeDouarin, 1987; Eagleson and Harris, 1990). This is supported by a later analysis of Danf expression, which remains present in dorsal regions of the anterior forebrain (Fig. 2D). The posterior, weaker domain of Anf expression in zebrafish and Xenopus may coincide, in its medial part, with the presumptive hypothalamic region and, in its lateral parts, with the position of presumptive zona limitans intrathalamica (zli), a boundary that divides ventral and dorsal thalamus. This is suggested by the location of this domain just rostral to the anterior end of the prospective floor plate, and second, by the result of double-labelling in-situ hybridization experiments with probes to Xanf-1 and Xotx2. In these experiments, we find that the posterior boundary of Xanf-1 expression coincides with the anterior boundary of the diencephalic–mesencephalic domain of the Xotx2 expression ( Fig. 2K, L), which is known to coincide with the zli (Boncinelli et al., 1993; Simeone et al., 1993; Mori et al., 1994). A similar location for the posterior boundary of Danf expression has been shown in zebrafish by comparison of Anf expression with that of flh, which is known to be expressed just dorsal to the zli (Barth et al., in preparation). Thus, early Anf expression divides the neural plate into two prospective forebrain territories corresponding to tissue rostral to the zli, which expresses both Otx and Anf genes and more posterior tissue that only expresses Otx genes. This subdivision is consistent with recent models of forebrain organization that place a fundamental subdivision of the forebrain at the zli ( Figdor and Stern, 1993; Puelles and Rubenstain, 1993; Macdonald et al., 1994). Anf genes are the earliest known genes to respect this subdivision, raising the possibility that they may be involved in its establishment. During further development, Anf expression is progressively down-regulated in its posterior domain and, by the end of neurulation, appears to be restricted exclusively to the medial part of the anterior domain. At the latest stage at which the expression can be detected by in-situ hybridization, transcripts are localized to the dorsal telencephalon in zebrafish ( Fig. 2D), and in all species examined to an ectodermal derivative initially connected with the presumptive telencephalon, O.V. Kazanskaya et al. / Gene 200 (1997) 25–34 the anterior pituitary anlage ( Fig. 2I, P; see also Hermesz et al., 1996; Mathers et al., 1995; Zaraisky et al., 1995; Barth et al., in preparation). Interestingly, the medial, more prominent part of the posterior Anf expression domain ( Fig. 2C and G) coincides with the floor of the rostral diencephalon, a region that includes cells of the prospective neurohypophisis. Therefore, it appears that both local high points of Anf expression, in the anterior neural ridge and near the rostral end of the floor plate, mark cells whose progenitors will contribute to the same definitive organ, the pituitary. As Anf genes are restricted in their expression to the most anterior part of the embryonic body axis and transcripts appear to be present in tissues derived from all three embryonic layers (in the meso-endoderm and in the neurectoderm), one may hypothesize that Anf genes in the forebrain region like Hox genes in the trunk region could be involved in specification of embryonic subdivisions [reviewed by Scott et al. (1989) and McGinnis and Krumlauf (1992)]. There is some experimental evidence supporting this hypothesis. When Xanf1 is ectopically expressed in cells of the ventral marginal zone of Xenopus early gastrulae, it is able to induce in these cells some properties normally characteristic of the dorsal anterior meso-endoderm, i.e. attraction to anterior locations and an ability to organize the formation of secondary embryonic axis at the ventral side of embryo (Zaraisky et al., 1995). In addition, overexpression of Xanf-1 in the neurectoderm can, in some cases, lead to the transformation of more posterior brain tissues to telencephalic structures (Zaraisky et al., in preparation). Another possible role of Anf genes may be connected with the regulation of pituitary differentiation. Thus, it has been shown recently, that in mouse, Rpx/Hesx-1 could be directly involved in the repression of early pituitary differentiation, inhibiting until stages 12.5–13.5 the expression of a pituitary-specific homeobox gene Prop-1 (Sornson et al., 1996). 4. Conclusions (1) We cloned cDNA of five novel genes homologous to the homeobox-containing genes Xanf-1 and Xanf2 of Xenopus and Hesx1/Rpx of mouse in sturgeon (Aanf ), zebrafish (Danf ), newt (Panf ), chicken (Ganf ) and human (Hanf ). Comparative analysis of the homeodomain primary structure of these genes revealed that they belong to a novel class of homeobox genes, which we name Anf. (2) Our data suggest that Anf class may be one of the most quickly evolving classes of vertebrate homeobox genes. (3) Early Anf expression divides the neural plate into 33 two prospective forebrain territories corresponding to tissue rostral to the zli, which expresses both Otx and Anf genes and more posterior tissue that only expresses Otx genes. This subdivision is consistent with recent models of forebrain organization that place a fundamental subdivision of the forebrain at the zli. Thus, Anf genes are the earliest known genes to respect this subdivision, raising the possibility that they may be involved in its establishment. Acknowledgement We would like to thank Oleg Vasiliev for technical assistance and fruitful discussions. We are also grateful to Anna Stornaiouolo, Antonello Mallamaci and Giovanni Lavorgna and Dominic Delaney for providing expert advice. We thank the Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine ( TIGEM ) for supplying the NT2/D1 library. This work was supported by grants from the Russian Human Genome Project, the Russian Foundation for Fundamental Investigations (95-04-11320a and 97-04-49883), and INTAS (95-INRU-1152) and Wellcome Trust funding to S.W. O.V.K. was supported by an EMBO East European fellowship. References Barnes, W.M., 1994. PCR amplification of up to 35-kb DNA with high fidelity and high yield from l bacteriophage templates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 2216–2220. Boncinelli, E., Gulisano, M., Broccoli, V., 1993. Emx and Otx homeobox genes in the developing mouse brain. J. Neurobiol. 24, 1356–1366. Burri, M., Tromvoukis, Y., Bopp, D., Frigerio, G., Noll, M., 1989. Conservation of the paired domain in metazoans and its structure in three isolated human genes. EMBO J. 8, 1183–1190. Chenchik, A., Diachenko, L., Tarabykin, V., Lukyanov, S., Siebert, D., 1996. Full-length cloning and determination of mRNA 5∞- and 3∞-ends by amplification of adapter-ligated cDNA. BioTechniques 21, 526–534. Chomczynski, P., Sacchi, N., 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate–phenolchlorophorm extraction. Analyt. Biochem. 162, 156–162. Couly, G.F., LeDouarin, N.M., 1987. Mapping of the early neural primordium in quail-chick chimeras. Dev. Biol. 120, 198–214. Desplan, C., Theis, J., O’Farrell, P.H., 1988. The sequence specificity of homeodomain–DNA interaction. Cell 54, 1081–1090. Detlaff, T.A., Ginsburg, A.S. Embryonic development of Acipenseridae and the questions of their breeding. USSR Acad. Sci. Press, Moscow 1954 (in Russian). Eagleson, G.W., Harris, W.A., 1990. Mapping of the presumptive brain regions in the neural plate of Xenopus laevis. J. Neurobiol. 21, 427–440. Figdor, M.C., Stern, C., 1993. Segmental organization of embryonic diencephalon. Nature 363, 630–634. Fritz, A.F., Cho, K.W., Wright, C.V., Jegalian, B.G., DeRobertis, E.M., 1989. Duplicated homeobox genes in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 131, 584–588. Furukubo-Tokunaga, K., Muller, M., Affolter, M., Pick, L., Kloter, 34 O.V. Kazanskaya et al. / Gene 200 (1997) 25–34 U., Gehring, W.J., 1992. In vivo analysis of the helix–turn–helix motif of the fushi tarazu homeo domain of Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 6, 1082–1096. Gallien, L., Durocher, M., 1957. Table chronologique du developpment chez Pleurodeles waltlii Michah. Bull. biol. France Belgique 91, 97–114. Gehring, W.J., Qian, Y.Q., Billeter, M., Furukubo-Tokunaga, K., Schier, A.F., Resendez-Perez, D., Affolter, M., Otting, G., Wuthrich, K., 1994. Homeodomain-DNA recognition. Cell 78, 211–223. Gibson, G., Schier, A., LeMotte, P., Gehring, W.J., 1990. The specificites of Sex combs reduced and Antennapedia are defined by a distinct portion of each protein that includes the homeodomain. Cell 62, 1087–1103. Hanes, S.D., Brent, R., 1989. DNA specificity of the bicoid activator protein is determined by homeodomain recognition helix residue 9. Cell 57, 1275–1283. Harland, R.M., 1991. In situ hybridization: an improved whole-mount method for Xenopus embryos. In: Kay, B.K., Peng, H.B. ( Eds.), Methods in Cell Biology: Xenopus laevis: Practical Uses in Cell and Molecular Biology, Vol. 36, pp. 685–695. Hawkins, N.C., McGhee, J.D., 1990. Homeobox containing genes in the nematode Caenorahabditis elegans. Nucl. Acids Res. 18, 6101–6106. Hamburger, V., Hamilton, H., 1951. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J. Morphol. 88, 49–92. Hermesz, E., Mackem, S., Mahon, K.A., 1996. Rpx: a novel anteriorrestricted homeobox gene progressively activated in the prechordal plate, anterior neural plate and Rathke’s pouch of the mouse embryo. Development 122, 41–52. Kappen, C., Schughart, K., Ruddle, F.H., 1993. Early evolutionary origin of major homeodomain sequence classes. Genomics 18, 54–70. Kimmel, C.B., Ballard, W.W., Kimmel, S.R., Ullmann, B., Schilling, T., 1995. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Deve. Dyn. 203, 253–310. Lin, L., McGinnis, W., 1992. Mapping functional specificity in the Dfd and Ubx homeodomains. Genes Devel. 6, 1071–1081. Lukyanov, K.A., Launer, G.A., Tarabykin, V.S., Zaraisky, A.G., Lukyanov, S.A., 1995. Inverted terminal repeats permit the average length of amplified DNA fragments to be regulated during preparation of cDNA libraries by polymerase chain reaction. Analyt. Biochem. 229, 198–202. Macdonald, R., Xu, Q., Barth, K.A., Mikkola, I., Holder, N., Fjose, A., Krauss, S., Wilson, S.W., 1994. Regulatory gene expression boundaries demarcate sites of neuronal differentiation and reveal neuromeric organisation of the zebrafish forebrain. Neuron 13, 1039–1053. McGinnis, W., Krumlauf, R., 1992. Homeoboxes and axial patterning. Cell 68, 283–302. Mathers, P., Miller, A., Doniach, T., Dirksen, M.-L., Jamrich, M., 1995. Initiation of anterior head-specific gene expression in uncommitted ectoderm of Xenopus laevis by ammonium chloride. Dev. Biol. 171, 641–654. Mori, H., Miyazaki, Y., Morita, T., Nitta, H., Mishina, M., 1994. Different spatio-temporal expression of three otx homeoprotein transcripts during zebrafish embryogenesis. Brain Res. Mol. Brain. Res. 27, 221–231. Puelles, L., Rubenstain, J.L.R., 1993. Expression patterns of homeobox and other putative regulatory genes in the embryonic mouse forebrain suggest a neuromeric organisation. Trends Neurosci. 16, 472–479. Richter, K., Good, P.J., Dawid, I.B., 1990. A developmentally regulated nervous system-specific gene in Xenopus encodes a putative RNA-binding protein. New Biologist 2, 556–565. Scholer, H.R., Ruppert, S., Suzuki, N., Chowdhury, K., Gruss, P., 1990. New type of POU domain in germ-line specific protein Oct-4. Nature 344, 435–439. Scott, M.T., Tamkun, J.W., Hartzell, G.W., 1989. III. The structure and function of the homeodomain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 989, 25–48. Siebert, P.D., Chenchik, A., Kellogg, D.E., Lukyanov, K.A., Lukyanov, S.A., 1995. An improved PCR method for walking in uncloned genomic DNA. Nucl. Acids Res. 23, 1087–1088. Simeone, A., Acampora, D., Mallamaci, A., Stornaiuolo, A., D’Apice, M.R., Nigro, V., Boncinelli, E., 1993. Two vertebrate homeobox genes related to the Drosophila empty spiracles gene are expressed in the embryonic cerebral cortex. EMBO J. 12, 2735–2747. Stein, S., Fritsch, R., Lemaire, L., Kessel, M., 1996. Checklist: Vertebrate homeobox genes. Mech. Dev. 55, 91–108. Sornson, M.W., Wu, W., Dasen, J., Flynn, S., Norman, D., O’Connell, S., Gukovshy, I., Carriere, C., Ryan, A., Miller, A., Zuo, L., Gleiverman, A., Andersen, B., Beamer, W., Rosenfeld, G., 1996. Pituitary lineage determination by the Prophet of Pit-1 homeodomain factor defective in Ames dwarfism. Nature 384, 327–333. Thomas, P.Q., Johnson, B.V., Rathjen, J., Rathjen, P.D., 1995. Sequence, genomic organization, and expression of the novel homeobox gene Hesx1. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 3869–3875. Thomas, P.Q., Beddington, R., 1996. Anterior primitive endoderm may be responsible for patterning the anterior neural plate in the mouse embryo. Curr. Biol. 6, 1487–1496. Xu, Q., Holder, N., Patient, R., Wilson, S.W., 1994. Spatially regulated expression of three receptor tyrosine kinase genes during gastrulation in the zebrafish. Development 120, 287–289. Zaraisky, A.G., Lukyanov, S.A., Vasiliev, O.L., Smirnov, Y.V., Belyavsky, A.V., Kazanskaya, O.V., 1992. A novel homeobox gene expressed in the anterior neural plate of the Xenopus embryo. Dev. Biol. 152, 373–382. Zaraisky, A.G., Ecochard, V., Kazanskaya, O.V., Lukyanov, S.A., Fesenko, I.V., Duprat, A.-M., 1995. The homeobox-containing gene XANF-1 may control development of the Spemann organizer. Development 121, 3839–3847.