CHAPTER FIVE HISTORIC CONTEXT FOR CAMBRIDGE

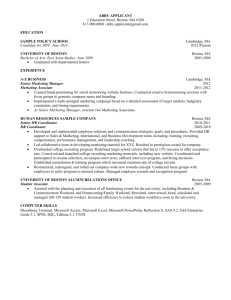

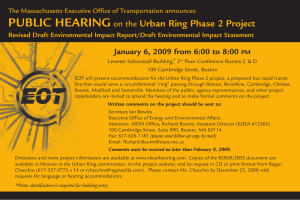

advertisement