CHAPTER THREE ENVIRONMENTAL CONTEXT

advertisement

CHAPTER THREE

ENVIRONMENTAL CONTEXT

The environmental context of a given area, including its geology, topography, hydrology, and natural

resources, plays a significant role in determining the nature of human activity that took place within it

over time. This chapter presents an overview of the environmental history of southern New England

with specific reference to the Urban Ring project area in the Boston, Brookline, Cambridge, Chelsea,

Everett, Medford, and Somerville areas, proceeding from macro-level considerations, such as the effects

of glacial activity in the Northeast, to site-specific conditions.

Geomorphology and Geology

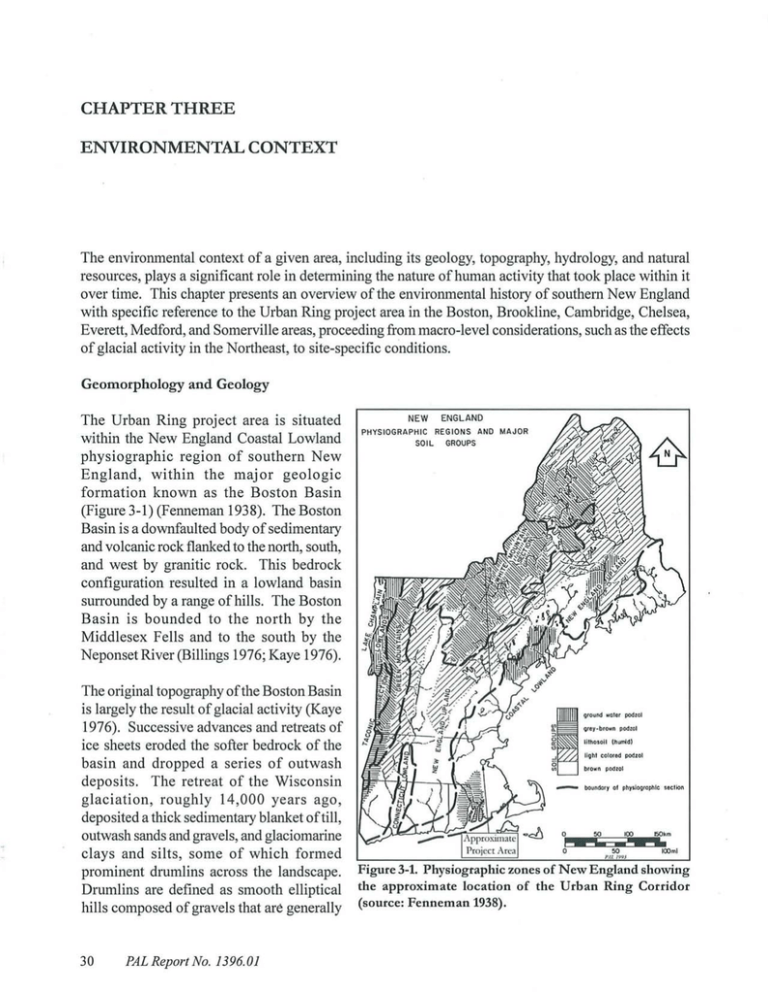

The Urban Ring project area is situated

within the New England Coastal Lowland

physiographic region of southern New

England, within the major geologic

formation known as the Boston Basin

(Figure 3-1 )(Fenneman 1938). The Boston

Basin is a downfaulted body of sedimentary

and volcanic rock flanked to the north, south,

and west by granitic rock. This bedrock

configuration resulted in a lowland basin

surrounded by a range of hills. The Boston

Basin is bounded to the north by the

Middlesex Fells and to the south by the

Neponset River (Billings 1976; Kaye 1976).

The original topography ofthe Boston Basin

is largely the result of glacial activity (Kaye

1976). Successive advances and retreats of

ice sheets eroded the softer bedrock of the

basin and dropped a series of outwash

deposits. The retreat of the Wisconsin

glaciation, roughly 14,000 years ago,

deposited a thick sedimentary blanket oftill,

outwash sands and gravels, and glaciomarine

clays and silts, some of which formed

prominent drumlins across the landscape.

Drumlins are defined as smooth elliptical

hills composed of gravels that are generally

30

PAL Report No. 1396.01

NEW

PHYSIOGRAPHIC

SOIL

ENGLAND

REGIONS AND MAJOR

GROUPS

I

gro,OO water pod.ol

~

qrey-brown podlal

~

IlthosOl1 (hWTld)

'"

...J

hoM colored podlal

II)

brown poozol

o

____

o

boundary ot physiographic section

50

100

I50km

:U._U.

o

50

100m!

PAl. 199J

Figure 3-1. Physiographic zones of New England showing

the approximate location of the Urban Ring Corridor

(source: Fenneman 1938).

Environmental Context

elongated in shape with the long axis considered indicative of the direction of ice flow. Within the

Boston Basin, however, drumlin shape varies greatly. This along with other evidence indicates that

glacial ice flowed into the area from various directions, ranging from the southwest to the east (Kaye

1976).

Distinct drumlins rise 100-200 feet above the plain to the west before dropping to sea level to the east,

where the surviving drumlins and moraines remain slightly above sea level to form the Boston Harbor

Islands. Many of the drumlins were leveled for materials to fill low-lying areas, but some are still

visible throughout the Basin today as low rounded hills including Beacon, Breeds, and Bunker hills in

Boston and Charlestown.

The bedrock underlying the project is part of the Milford-Dedham Tectonic Zone, a lithotectonic

subdivision consisting of upper Proterozoic quartzite, volcanic, and plutonic rocks extending across

the Boston region, southeastern Massachusetts, Cape Cod and into northern Rhode Island (Zen et al.

1983). The bedrock is typically oriented from the southwest to the northeast, following the tectonic

plate. A secondary system of north-south faults enabled watercourses such as the Malden, Mystic, and

Aberjona rivers to flow out of the Middlesex Fells. The granites, gneisses, dolomites, and felsites are

visible in exposed ledges in the Blue Hills and the Middlesex Fells. In different areas, these rocks may

be intruded by granites, metamorphosed to gneiss, or overlain and cut by rocks from other zones.

Two major rock classifications are recorded for the Boston area: Cambridge and Braintree Argillite and

the Roxbury Conglomerate. The Cambridge and Braintree Argillite underlies most of the Boston area,

Chelsea, and Everett and consists of gray argillite, some quartzite, and small amounts of sandstone and

conglomerate deeply buried under glacial outwash deposits (Clapp 1902). The argillite was an important

lithic raw material for the manufacture of chipped-stone tools by pre-contact period Native American

populations in the northern Boston Basin and several river drainages to the west. During the post­

contact period the argillite along with slate was used for building material (foundation stone, roofmg

slate) and gravestones. Quarries operated during the Colonial Period (1675-1775) were located nearby

in Medford and Somerville (MHC 1981 d). Between the Boston Basin and the Blue Hills is the Roxbury

Conglomerate called "puddingstone." Though difficult to quarry, the Roxbury Conglomerate was used

as a building material.

Glaciation also influenced the coastline and drainages in the Boston Area. Rising sea levels, local

topography, and crustal rebound produced a flooded landscape. The retreat of the glacier also created

a network of swamps and kettle ponds, while the rising sea levels turned formerly freshwater rivers into

wide tidal estuaries such as the lower Charles and Mystic rivers.

Hydrology

The Urban Ring project area is located within the Charles and Mystic river drainages (Figure 3-2). The

project area lies primarily within the Charles River watershed. Beginning in Hopkinton, the Charles

River meanders for 80 miles and drains 308 square miles in 35 municipalities before emptying into

Boston Harbor (CRWA 2007). The river is generally divided into three subregions: the rural upper

basin, the suburban lakes or middle region, and the urban lower region. The project area is within the

lower basin, where the Charles River converges with another major watershed, the Mystic River at the

PAL Report No. 1396.01

31

Chapter Three

VERl\IO:'iT

r"-" "-'----,,"--'-'1'----._-_.

"

Deerfield

),.)

",,-"'*\.~r-',j

1:'

co '

;- I

~

~

.

/1I00SI

!

!

,"

~

~

'ECTICJ.T

(

/'

':-~""

<:::. '

fI

Millers

·\."r'l.".-f"'""\.·

r;,..

•

:"lEW 11.~\IPSllUill

7

/"

Chicopee

\.1-../'"

O-.. _.. _.. ~~~J.:~::J\'

CON:"IECTICUT

~JajOi' drainage

basin

1l00SIC

_

...- . J.... ~

~linOi'

drainage hasin

'nshun

DRANAGE BASIi'\S OF MASSACHUSETTS

.0

C~~1~0 iiiiiiiiil2!!0~!J30~~-t0.!

mi

Figure 3-2. Map of drainage basins of Massachusetts showing the approximate location of the Urban

Ring Corridor.

western portion of Boston Harbor. The urban lower basin is fOlmed by the tidal estuary of the Charles,

and extends 8 miles upstream from Boston Harbor to Watertown Square. This section of river was

subject to the ebb and flow of the tides until the completion of the Charles River Dam near the harbor

in the early 1900s. Almost the entire length of the estuary was characterized by salt marshes until the

early post-contact period.

The Mystic River drains Everett, Chelsea, Medford and parts of Somerville of the project area. The

Mystic River has a total length of 17 miles and meanders northwest to southeast. The headwaters ofthe

system begin in Reading and form the Abeljona River, which flows into the Upper Mystic Lake in

Winchester. The Mystic River flows from the Lower Mystic Lake through Arlington, Medford,

Somerville, Everett, Charlestown, Chelsea, and East Boston before emptying into Boston Harbor (MRWA

2007). The Mystic River drains approximately 66 square miles. Tributary streams of the Mystic River

include Little River/Alewife Brook and Mill Brook. The Little River flows out of Little Pond in an

east/southeast direction, becoming Alewife Brook at the Belmont/Arlington town line. Alewife Brook

flows north for a distance of about 2 miles before joining the Mystic River. In the post-contact period

prior to construction of dams and other obstructions, the confluence of Alewife Brook and the Mystic

River was at the upper limits of tidallestuarine conditions in the Mystic drainage.

32

PAL Report No. 1396.01

Environmental Context

Soils

The generalized surficial geology map of the Boston area identifies three general soil types: glacial

tills; sand gravels overlying coastal plain deposits; and silt, sand, clay, and organic materials (Figure 3­

3). The more specific soil classifications indicate that the Urban Ring occupies soils classified as

Udorthents-Urban Lands. These are very deep, nearly level to moderately steep, loamy and sandy soils

that have been altered.

The classification of urban land is so large that several subclasses are defined. Most of the project

corridor occupies urban lands built upon wet substratum. These are typically areas that, prior to the

1700s, were small islands surrounded by bays, estuaries, tidal marshes, river floodplains, harbors, and

swamp.

The creations of made lands through cutting down of hills and filling low-lying areas is the most

dominant force resulting in the current topography of the Boston area. Substantial portions of Boston

are composed of landfill, including major sections of East Boston, South Boston, and Cambridge.

Landfill operations have occurred through much ofthe history of Boston and are a tangible result ofthe

historical development (Figure 3-4). Initial episodes of fill consisting of rubbish were small-scale

operations in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Later, large-scale operations to create residential

areas occurred in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and often incorporated "clean fill" imported

from outside the area.

Description of Communities within the Project Corridor

Boston

The City of Boston is located along the eastern shore of Massachusetts.. It is a sprawling, irregularly

shaped city, bordered by many smaller towns. On the north, Boston is flanked by Watertown, Cambridge,

Somerville, Everett, Revere, and Chelsea. To the east of Boston is the Atlantic Ocean, on the southeast

the city is bordered by Quincy and Milton, and on the southwest by Dedham and Needham. On the

west, Boston borders Newton and Brookline. Most of the western boundary of Boston is shared with

Brookline, of which the city surrounds almost 75 percent. The topography of the city is generally flat,·

with only a few scattered hills rising above 100 feet and none more than 300 feet above sea level. Much

of the present land of the city consists of tidal flats that have been filled over the past four hundred

years. Three of the highest elevations in the city were cut down over the same period, providing some

of the material for these fills. The city is drained by the stream systems of the Neponset River at its

southern border, the Muddy River on its west, and by the Charles River to the north (MHC 1981a).

AUston

The neighborhood of Allston in Boston was originally part of the separate town of North Brighton. It

comprises the 4 square mile eastern portion ofAllston/Brighton, which occupies the northwest lobe of

the City of Boston between the town of Brookline to the south and the wide curve of the Charles River

to the north and northeast. The majority of the neighborhood lands that now occupy Allston/Brighton

were originally dominated by tidal estuary marshlands. The tidal estuary setting of the area existed

PAL Report No. 1396.01

33

Chapter Three

N

ESSEX

0

~

~~

7.,.;-,

c

"

o

<'

"'­

__ 7~

~0

---

o

o{'?

I

f

O~'1'

+ - 42'20'

[J-Qt

Massachusetts

<')/

/

Bay

+

/

-42'10'

j

70'50'

LEGEND

Scale 1: 253,440

0

2

3

1

I " ,I

I

0

4

I, I

I

1

4 Miles

I

I

8 Km

I

I

~

~

~

~

Glacial till.

Sand and Gravel.

Sill, sand, clay and organic material.

Glacial till overlying Coastal Plain deposits.

Sand and gravel overlying Coastal Plain deposits.

Figure 3-3. Generalized surficial geology map, Norfolk and Suffolk Counties, Massachusetts showing

the approximate location of the Urban Ring Corridor.

34

PAL Report No. 1396.01

Environmental Context

N

o

t

1/2 Mile

!

Land filled to

1990's shoreline

1600's Marsh

Figure 3-4. Graphic depiction of fill episodes around Boston with the approximate location of the Urban

Ring Corridor (source: Muir 2000).

well into the nineteenth century and filling has been ongoing through the twentieth and early twenty

first century, primarily as a result of industrial developments and Harvard University's business school

and athletic facilities.

Charlestown

Charlestown is located on a peninsula in the northernmost pmi of Boston, where it extends from the

west shore into Boston Harbor. It is bounded on the north by the Mystic River, on the east by Boston

Harbor and the Charles River, on the south by the Charles River and Cambridge, and on the west by

Somerville. The original land area of the peninsula was approximately 425 acres, to which an additional

PAL Repol't No. 1396.01

35

Chapter Three

400 acres were added by 1910 through filling. The dominant topographic features of the peninsula are

two drumlins: Breeds Hill on the east end and Bunker Hill (elevation 113 feet) on the west. With the

exceptions of the two rivers that make up its borders, Charlestown has no other inland streams or

bodies of water (MHC 1980c).

Dorchester

The neighborhood of Dorchester is located to the south of Boston Proper, south of Roxbury and with

Dorchester Bay to its east. Originally settled as an independent town, Dorchester was annexed in

sections by Boston during the nineteenth century, with the final annexation in 1870. Its 9.7 square

miles of area rise gradually from the east coastal flats to heights of between 50 and 100 feet near

Dorchester Center. The highest elevation in the neighborhood is Wellington Hill (approximately 170

feet) one of approximately 15 drumlins that rise above the generally flat plain. The Neponset River,

which forms the southern boundary of Dorchester, is the drainage basin for the area (MHC 1980b).

East Boston

The community of East Boston is made up of five former islands located at the confluence of the

Mystic and Charles rivers. Noddles Island, the primary island of the settlement, is one-third of a mile

due northeast of Boston Proper, and consisted of 666 acres of upland and marsh at the time of its

settlement, with three large hills. Beginning in the early nineteenth century, the tidal flat surrounding

the five islands was filled with material excavated from the three hills (Camp, Smith, and Eagle) on the

island. The fill process, which continued into the twentieth century, added a land mass of more than

2,000 acres to the 666 of Noddles Island and 785 of Hog (Breed's) Island, and enveloped Governor's,

Apple, and Bird islands (MHC 1980a).

Roxbury

The community of Roxbury is located to the south of Boston Proper, at the base of the neck of land

upon which the city was originally built. The topography of Roxbury is generally sloping, rising from

east to west, up to a height of200 feet above sea level. A prominent ridge of drumlins is located in the

nOliheast part of Roxbury, while the highest elevation is Bellevue Hill, at 370 feet. Roxbury is drained

by four brooks, all of which empty into the Charles River (MHC 1981 b).

Brookline

The town of Brookline is located in the nOlihern portion of Norfolk County, Massachusetts. It

encompasses an area of approximately 6.2 square miles in the Charles River Watershed. The town is

bounded by Boston on the north, east, and south, and by Newton on the west and north. Brookline was

originally bounded by the towns of Roxbury (now in Boston) and Cambridge (now Newton). Much of

the southern part of the town, which is primarily a plateau, drains into the upper Charles River via Saw

Mill Brook. The northern areas are dominated by a row of prominent drumlins: Corey, Aspinwall,

Fisher, and Single Tree hills, running from north to south. The Muddy River is Brookline's principal

stream, and forms pmi of the town's eastern boundm)' with the neighborhood of Roxbury. It is fed by

36

PAL Report No. 1396.01

Environmental Context

both the Village and Tannery brooks. The Brookline Reservoir, the town's largest body of water, was

built by the city of Boston in the 1840s (MHC 1980g).

Cambridge

The City of Cambridge contains 6.2 square miles of heavily developed land on the west side of Boston.

It is bordered on the west by Belmont and Arlington and on the north by Somerville. The eastern border

runs down the center of the Charles River, with Boston on the east bank. The Charles River continues

southwest to form Cambridge's southeastern boundary, before turning south again at the beginning of

Cambridge's southwestern border with Watertown. The city is primarily flat, with low hills in the

western portion terminating at MountAuburn,just over the city line in Wateliown. West of these hills,

the land drains into the Mystic River, to the north, predominantly by way of Alewife Brook, while the

eastem portion of the city drains into the Charles River, to the south. In the western part of the city, the

dominant water feature is the kettle hole known as Fresh Pond. A significant amount of low-lying salt

marsh along the Charles River has been filled to create what, in the nineteenth century, became largely

industrial land along the riverbank (MHC n.d.)

Chelsea

The City of Chelsea occupies 1.86 square miles on a peninsula formed by the Mystic and Charles rivers

and Mill Creek. It is bordered on the nOlih by Revere; on the east by the Chelsea River, which separates

it from Revere and East Boston; on the south by East Boston and Charlestown; and on the west by

Everett. The city was formerly surrounded by marshes that were divided by several small streams.

From the salt marshes, the surface of the town rises to four considerable drumlins that dominate the

topography: Mts. Washington and Bellingham, Powder Hom Hill (230 feet), and Naval Hospital Hill.

The western slope of Chelsea drains into the Island End River, a small tributary of the Mystic, while the

rest of the city is drained by the Chelsea River (MHC 1980d)

Everett

The City of Everett is located to the north of Boston Proper and west of Chelsea. It is bounded on the

south by the Mystic River, on the west by the Malden River, on the north by Malden, and on the east by

Chelsea and Revere. The 3.75 square miles of the city are primarily flat and below 50 feet in elevation,

with three drumlins, Mount Washington (175 feet), and Corbett and Belmont hills rising in the nOliheast

part of the city. Everett has a large amount of residential architecture, with its industrial sector running

along most ofthe city's shoreline ofthe Mystic and Malden rivers. The town was originally established

as Mystic Side in 1629. In 1730, after existing as a pali of Malden for a number of years, South Malden

parish was established as an independent entity. This status was lost during the Revolutionary War, and

it would be 1870 before Everett would regain its status as a town, and 1892 before it would become a

city (MHC 1981c).

Medford

The City of Medford consists of approximately 8.6 square miles of densely developed land located

approximately 5 miles northwest of Boston. The city is bordered on the north by Winchester and

PAL Report No. 1396.01

37

Chapter Three

Stoneham, on the east by Malden, Everett and the Malden River, on the south by Somerville, and on the

west by Arlington and the Upper and Lower Mystic lakes. The Mystic River runs through the center of

the city and is the primary drainage for the city. Much of the northern section of the city consists of the

Middlesex Fells Reservation (MHC 1981d).

Somerville

The City of Somerville consists of approximately 4.1 square miles of densely developed land located to

the northwest of Boston. The city is bordered on the north by Medford and the Mystic River, on the east

by the Mystic River and Charlestown, on the south by Cambridge, and on the west by Arlington. The

topography of Somerville is generally flat, with the high points amid a cluster ofdrumlins located in the

eastern half of the town. Winter and Spring hills rise to heights of 42 and 39 meters, respectively, with

Prospect Hill, to the southeast, reaching 30 m. Northeast ofthe two higher hills, the land drains into the

Mystic River, while the southwest areas once drained into the now-extinct Miller's Creek. Alewife

Brook, flowing nOlih, makes up the boundary between Somerville and Arlington (MHC 1980e).

38

PAL Report No. 1396.01

CHAPTER FOUR

PRE-CONTACT AND CONTACT PERIOD CULTURAL CONTEXT

An understanding of regional long-term human settlement and subsistence practices is critical to

understanding those same issues within a given project area. The Charles and Mystic river drainages,

with their numerous tributaries, lakes, and wetlands, have been a focal point for human occupation.

This chapter provides an overview of the pre-contact period Native American history of southern New

England generally, and the Urban Ring COlTidor area specifically. This review is by no means exhaustive,

but provides a framework within which to predict and interpret pre-contact period archaeological

resources identified within the project area. The infOlmation for this context has been drawn from the

results of professional CRM surveys, through a review of state site files at the MHC, pre-contact and

contact period cultural histories, site-specific histories, and the collections ofavocational archaeologists.

Archaeological Research in the Charles River Basin

Early studies of the Charles River Basin emerged in the 1860s amidst the antiquarian movement of

museum scholars and boosters. By the tum ofthe century, Harvard University's Peabody Museum was

supporting numerous salvage excavations along the Charles River estuary in Boston. Investigations by

nineteenth-century museum directors Jeffries Wyman and Frederick Putnan1 identified several large

sites along the estuary and set the stage for later studies by Charles Willoughby in the 1930s.

In 1939, Dr. Maurice Robbins of Mansfield, Massachusetts founded the MAS, effectively drawing the

interests of artifact collectors and professionals toward a common goal. During the initial years, MAS

chapters formed across southeastern and eastern Massachusetts, including Cape Cod and Nantucket,

and archaeological excavations went forward. In 1940, MAS organized a statewide inventory ofknown

sites and resulted in the recognition of archaeological sites and collectors in the towns of Holliston

(Lawrence Gahan), Medfield (Elwyn Chick), Millis (Frank Porter), Franklin (Ralph Hoar, Albert

Levasseur), and Milford (Stanley Roop).

One of the most significant sites identified during tlus period was in the town of Milford on the banks

of the Mill River. Originally documented in the early twentieth century by C.C. Willoughby, and

inventoried in 1940, MAS members conducted extensive excavations there in the early 1960s (Roop

1963 :21-25). Much of the published information from these amateur efforts remained focused on

either the functional interpretation of tools and tool assemblages, or on determining their relative

chronologies.

The development and subsequent implementation of cultural resource legislation in the late 1960s and

tlu'oughout the 1970s coincided with a rapid expansion of avocational archaeology. Section 106 of the

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 recognized the significance of archaeological resources,

PAL Report No. 1396.01

39

Chapter Four

and provided a mechanism to insure that federal undertakings take into consideration their effects on

these properties (36 CFR 800).

In 1967, Dr. Dena Dincauze conducted the first comprehensive survey ofpre-contact sites in the Charles

River basin as part of a larger watershed study initiated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Northeast

Region. The goals of the project were elemental: "... to broaden the basis of knowledge about the

Indian occupation and the archaeological potential of eastern Massachusetts" (Dincauze 1968b:iii).

Sources of information consulted included geologicalpublications, town histories, nineteenth-century

survey maps, late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century anthropological literature, site data compiled by

the MAS, museum collections, local historical society collections, and private collections.

Dincauze's survey resulted in several significant conclusions and a set of generalized observations

about pre-contact site patterning within the boundaries of the Charles River basin. From the available

site information, she concluded that site size correlated with the size of the adjacent expanse of fresh

water. Specifically, most larger, multicomponent sites were situated on the margins of freshwater lakes

or ponds or at fall locations on the Charles upstream from Populatic Pond in Medway. This pattern was

considered directly related to the availability of large quantities of fish, since fresh water was a

"dispensable luxury" to the Native Americans living in this area (Dincauze 1968b:30). Other notable

correlates between site frequency and specific environmental conditions included a preference for well­

drained light gravel or sandy soils, and to a lesser degree, southern exposures.

Subsequent to the 1967 survey, Dincauze proposed a settlement model exclusive to the Charles River

estuary. Using sea-level data, she was able to cOlTelate the westward, upriver migration ofthe intertidal

zone during the Holocene with pre-contact settlement (Dincauze 1973). The effects of sea-level rise on

interior sections of the Charles River were not considered in this study. Data gathered during the 1967

archaeological survey also resulted in a proposed technological sequence of ceramic manufacture for

the Charles River territOly. Although the study sample was very small and geographically limited,

Dincauze noted a regional parallel with a "marked preference for smoothed vessel bodies in the Charles

basin collections" (Dincauze 1975: 14).

In 1980 the MHC proposed a simplified pre-contact settlement model within the geographical scope of

its state boundaries (MHC 1980h). At the same time, for the purposes of long-range planning, they

initiated an inventory ofthe state's historic and archaeological resources. Nine study units were proposed,

each of which corresponded with a specific environmentally defmed region (Cape and the Islands,

Boston Basin, Eastern Massachusetts, etc.). Individual town reconnaissance repOlts were also prepared

by the MHC during this period.

In several ofthese early planning documents, the MHC adopted a culturallhistorical geography approach

to pose a conceptual framework for future CRM projects (MHC 1980h: 11). On a statewide scale, a

functional relationship was hypothesized between pre-contact use of lowland and upland areas, based

on previously studied Euro-American settlement patterns throughout the state. Core areas of cultural

and economic diversity were defined in the lowlands, with associated fringe areas in the uplands,

linked together by transpOltation corridors (MHC 1980h:27).

40

PAL Report No. 1396.01

Pre-Contact and Contact Period Cultural Context

Pre-Contact Period

This section summarizes the available information about regional pre-contact Native American land

use. The discussion is segmented into temporal periods that are considered by archaeologists to mark

changes in social organization, settlement patterns, technology, and/or subsistence practices (Table 4­

1). Temporal assignments are based on radiocarbon dates derived from samples of organic materials

that have been collected in association with Native American artifacts. Identified archaeological sites

in the project vicinity are discussed within this framework to better understand Native American

settlement in the vicinity and to develop predictive statements about Native American cultural resources

within the project area.

PaleoIndian Period (12,500-10,000 B.P.)

The earliest evidence for human occupation of New England dates from the PaleoIndian Period. The

retreats of the Laurentide ice sheet and the Wisconsin glacier approximately 14,000 years ago resulted

in the moderation of climatic conditions. Tundra-like environmental conditions supported small, highly

mobile bands of PaleoIndian hunters. These bands covered large territories to exploit post-Pleistocene

resources such as megafauna, including mastodon, bison, elk, and caribou, medium and small game,

marine resources, and seasonally available flora (Dragoo 1976; Snow 1980). This specialized subsistence

model has its derivation from Midwestern PaleoIndian sites that clearly exhibit evidence for the

exploitation of these large animal species by humans. To date, there is no clear evidence, however, for

an association between large extinct animal species and PaleoIndian artifacts in southern New England

(Dincauze 1993; Odgen 1977).

Diagnostic artifacts temporally associated with the PaleoIndian Period include Clovis fluted and Eden­

like projectile points. Channel flakes are a diagnostic by-product of the production of these fluted

projectile points. Other stone tools associated with this period include scraping tools, gravers, and

drills. Many of the PaleoIndian tools recovered in the Northeast were formed from materials such as

chert and flint obtained outside the region. However, lithic material types from New England, such as

Saugus Jasper and Neponset Rhyolite, were also used for manufacture of stone tools by PaleoIndian

populations in the region (Gramly and Funk 1990; Ritchie 1994b). Many larger sites in the region

appear to have been either long-term or repeatedly used encampments (Robbins 1980). Smaller sites

consist of isolated projectile point finds, quarry workshops, habitation sites, kill-butchery sites, and

tool caches. PaleoIndian sites are frequently located on stable, well-drained, and elevated glacial or

early Holocene landforms as well as in river valleys and on the margins of glacial lake basins (Nicholas

1988).

The PaleoIndian Period is generally underrepresented in southern New England but several important

sites have been identified in Massachusetts. Two well-documented occupations include the

multicomponent encampments at the Bull Brook Site in Ipswich and PaleoIndian loci at the Neponset/

Wamsutta Site in Canton. The Bull Brook Site, dating to at least 9,000 B.P., covered several acres and

yielded thousands of artifacts including more than 175 fluted points, scrapers, and assorted stone tools

(Byers 1954; Grimes 1980; Grimes et al. 1984). Isolated finds of fluted PaleoIndian projectile points

have been documented from terraces overlooking the Charles, Connecticut, Mill, and Mystic rivers

(MHC 1981a).

PAL Report No. 1396.01

41

.j::>.

tv

Table 4-1. Native American Cultural Chronology for Southern New England.

n

::r­

~

'0

......

(1)

IDliNTlF/ED TI1/HI'ORAL

~

PERIOD

YEARS

Palcolndian

12,500-10,000 B.P.

(10,500-8000 1J.e.)

I

Early

Archaic

I

t--o

~

~

Cl

--:

.....

~

......

SUIJDIVU/ONS

CUUVIVlLASI'ECfS

• Eastern Clovis

• Plano

Exploitation of migratory game animals by highly mobile bands of hunter-gatherers with a specialized

lithic technology.

10,000-7500 H.P.

(8000-5500 H.C.)

• Bifurcate-Base

Point I\ssemblages

Few sites are known, possibly because of problems with archaeological recognition. This period represents

a transition from specialized hunting strategies to the beginnings of more generalized and adaptable

hunting and gathering, due in part to changing environmental circumstances.

Middle

Archaic

7500-5000 B.P.

(5500-3000 H.C.)

•

•

•

•

•

Regular harvesting of anadramous fish and various plant resources is combined with genera!.ized huntiJ1g.

Major sites are located at falls and rapids along over drainages. Ground-stone technology first utilized.

There is a reliance on local lithic materials for a variety of bifacial and unifacial tools.

Late

Archaic

5000-3000 B.P.

(3000-1000 H.C.)

• Brewerton

• Squibnocket

• Small Stemmed

Point Assemblage

lntensive hunting and gathering were the rule in diverse environments. Evidence for regularized shellfish

exploitation is first seen during tlus period. Abundant sites suggest increasing populations, with

specialized adaptations to particular resource zones. Notable differences between coastal and interior

assemblages arc seen.

Transitional

3600-2500 IJ.P.

(1600-500 H.e.)

•

•

•

•

Atlantic

Watertown

Orient

Coburn

Same economy as the earlier periods, but there may have been groups migrating into New England, or local

groups developing technologies strikingly different from those previously used. Trade in soapstone became

important. Evidence for complex mortuary rituals is frequently encountered.

Early

Woodland

3000-1600 IJ.P.

(1000 IJ.C.-.I.D. 300)

• Meadowood

• Lagoon

A scarcity of sites suggests population decline. Pottery was first made. Little is known of social organization

or economy, although evidence for complex mortuary rituals is present. lnfluences from the midwestern

Adena culture arc seen in some areas.

Middle

Woodland

1650-1000 IJ.P.

(A.D. 300-950)

• Fox Creek

• Jack's Reef

Economy focused on coastal resources. Horticulture may have appeared late in the period. Hunting and

gathering were still important. Population may have increased from the previous low in the Early

Woodland. Extensive interaction between groups throughout the Northeast is seen in the widespread

distribl;tion of exotic lithics and other materials.

Late

Woodland

1000-450 B.P.

(,I.D.950-1500)

• Levanna

Horticulture was established in some areas. Coastal areas seem to be preferred. Large groups sometimes

lived in fortified villages, and may have been organized in complicated political alliances. Some groups may

still have relied solely on hunting and gathering.

ProtoHistoric

and Contact

450-300 B.P.

(A.D. 1500-1650)

• Algonquian

Groups such as the Wampanoag, Narragansett, and Nipmuck were settled in the area. Political, social, and

economic organizations were relatively complex, and underwent rapid change during European

colonization.

2

Vv

\Q

9\

c::.

......

""t.

1

"­

I

2

Termed Phases or Complexes

Before Present

Neville

Stark

Merrimack

Otter Creek

Vosburg

'Tj

o

s=

""t

Pre-Contact and Contact Period Cultural Context

Within the northern Boston basin, a small PaleoIndian component, consisting of a fluted projectile

point, point prefOlms, and some other tools, has been located at the Saugus Quarry Site (Grimes et al.

1984). This site component, situated near an outcrop of high quality fine grained, red-pink rhyolite,

Saugus Jasper, is the earliest known occupation of this area. Other isolated finds of possible late

PaleoIndian Eden type projectile points have been reported from the Goat Acre Site in Arlington and

another farther north of Fresh Pond at Ossini's Garden in Wakefield. The lack of excavated PaleoIndian

sites in the greater Boston area makes it difficult to predict where these sites may be found. In general,

they are often on high ground adjacent to major rivers or marine estuaries. Changes in sea level in the

Boston area may have resulted in the submergence of many of these sites. To date there are no recorded

PaleoIndian sites in the City of Boston.

Early Archaic Period (10,000-7500 B.P.)

The Early Archaic Period is characterized by a gradually warnler and drier climate, referred to as the

Hypsithermal Period. This paleoenvironment was dominated by a mixed pine-hardwood forest and

would have made seasonally available food resources more predictable and abundant, allowing pre­

contact period populations to exploit a wide range ofterritories. Populations of megafauna began to be

replaced by smaller game such as deer and bear. The lithic technology ofthe Early Archaic reflects a

more diversified subsistence strategy, including beaked unifacial edge tools, cores, flakes, han1IDerstones,

milling slabs, and notched pebble sinkers, indicating an increased utilization ofplant and fish resources

(Robinson 1992). Corner-notched, stemmed, and bifurcate-based points serve as the diagnostic artifact

class for the period. Characteristic of both assemblage types is the predominance of expedient tools

made from local lithic sources.

Settlement strategies during this period remain somewhat speculative, but evidence from eastern

Massachusetts river drainage studies, such as Ritchie's review ofSudbury and Assabet drainages, indicate

that a complex multisite settlement system had been established by this period, with different site

locations indicating exploitation ofvaried resources and environmental settings (Johnson 1993; Ritchie

1984). Populations most likely increased during this period, although known sites are poorly represented

in the archaeological record. The nearly exclusive use of local stone for tool production also suggests

a more settled lifestyle.

Several Early Archaic sites have been reported from the greater Boston area in the Charles, Mystic, and

Neponset drainages (Dincauze 1974). Find spots of diagnostic bifurcate-based points from this time

period include materials from Goat Acre in Arlington, the Watertown Arsenal in Watertown, Ossini's

Garden and the Water Street Cluster in Wakefield, two locations in Cambridge, and Deer Island. Two

bifurcate-based projectile points were recovered from sites along Beaver Pond in Franklin in the upper

Charles River basin (Strauss 1990). Except for these projectile point finds, the artifact assemblages

associated with the Early Archaic Period are uncommon and little is known about the pre-contact

Native American lifeways at tIns time. It has been suggested that there is a greater occurrence of

artifacts and lithic debitage of non-local lithic materials, including chelis, at these early sites (Johnson

1993). As is the case with PaleoIndian sites, some Early Archaic sites may now be underwater (Dincauze

and Mulholland 1977).

PAL Report No. 1396.01

43

Chapter Four

Middle Archaic Period (7500-5000 B.P.)

The distribution and somewhat higher density of Middle Archaic Period sites indicates that a multisite

seasonal settlement system was firmly established by this time. Indications of a fairly intricate settlement

pat-tern are emerging from the distribution of Middle Archaic components in a variety of riverine and

upland environmental settings and they range in site size, function, and internal complexity. Included

are large base camps, which appear to have been used repeatedly over a number of generations, usually

located near riverine wetlands.

Sites from this period also appear to cluster around falls and rapids along major river drainages, where

the harvesting of anadromous fish and various flora resources was combined with generalized hunting

practices (Bunker 1992; Dincauze 1976; Doucette and Cross 1997; Maymon and Bolian 1992). The

seasonal pursuit of anadromous fish species may have developed in response to the development of

socioeconomic territories defmed by major river drainage basins (Dincauze and Mulholland 1977).

Climatic and biotic changes continued and deciduous forests of oak, beech, sugar maple, elm, ash,

hemlock, and white pine began to emerge. By this time, the present seasonal migratory patterns of

many bird and fish species had become established (Dincauze 1974) and important coastal estuaries

had developed (Barber 1979).

Neville, Neville-variant, and Stark stemmed projectile points, as well as semilunar knives and bifacial

prefOlms mark the Middle Archaic Period in southern New England (Dincauze and Mulholland 1977;

MHC 1984; Ritchie 1979). Ground-stone technology introduced a variety of tool types into the lithic

assemblage including net sinkers, plummets, grooved adzes, axes, gouges, whetstones, and atlatl weights

(Carlson 1964; Dincauze 1976; Fowler 1950). Excavations at Annasnappet Pond in Carver,

Massachusetts have conclusively linked the emergence of atlatl weights to this period (Cross 1999;

Doucette and Cross 1997). The presence of adzes, gouges, and axes suggests heavy woodworking and

possibly the appearance of dugout canoes.

A preference for locally available lithic raw materials for a variety ofbifacial and unifacial stone tools

is also evident at many sites. Local Westborough formation quartzite or mylonite and rhyolite or felsite

from sources in the Blue Hills and Charles-Neponset River drainage area were used for Neville points;

Stark points were primarily chipped from distinctly local lithic mate-rials such as quartzite, crystal tuff

and amphibolite schist or argillite from source areas in the Charles River drainage. The local quartzite,

mylonite, crystal tuff and amphibolite schist were quarried from bedrock outcrops located in upland

sections of the Sudbury/Assabet drainage (Ritchie 1979). For example, quartzite, available as riverine

and glacial cobbles in many parts of Massachusetts, were used for chipped-stone tools.

Middle Archaic sites are more common throughout the greater Boston area than those dating to the

Early Archaic. Sites from this period are known from Braintree, Hingham, Randolph, Weymouth, as

well as from numerous adjacent towns. Sites include collections from Spy Pond and the Goat Acre Site

on the Mystic River, the Wyman Falm Site on Alewife Brook in Arlington, the Watertown Arsenal,

Cedar Hill and the Old Perkins Estate in Wakefield, the Red Fox Site in West Roxbury and collections

from the Arnold Arboretum in Jamaica Plain. A large site, probably established to exploit anadromous

fish runs, has been identified at Magazine Beach in Cambridge in a location that would have lain at the

head of the tide of the Charles River during the Middle Archaic (MHC site files).

44

PAL Report No. 1396.01

Pre-Contact and Contact Period Cultural Context

Late Archaic Period (5000-3000 B.P.)

The Late Archaic Period was marked by a climatic shift to drier and slightly warmer conditions with a

significant decrease in precipitation. During this period, oak, pine, and beech reached their full extent,

and wetlands became more abundant along river margins. Wetland and estuarine areas appear to have

been used extensively based on site distribution. The increase in density of sites and artifacts from this

period in southem New England coincides with this climatic warming (Funk 1972). The archaeological

evidence demonstrates an increased use of shellfish and nuts, and the construction of fishweirs such as

the Boylston Street Fishweir in Boston. Perhaps in response to an increasingly resource-rich natural

environment, Late Archaic populations expanded and diversified.

The Late Archaic Period is comprised of three major cultural traditions: Laurentian, Small Stemmed,

and Susquehanna. The Laurentian tradition is the earliest phase of Late Archaic activity in the region.

Vosburg (MiddlelLate), Otter Creek (MiddlelLate), Brewerton (Middle/Late), and Broad Eared projectile

point types mark this tradition. These points are manufactured primarily from locally available materials

such as quartzite and rhyolite. Site distributions from the Laurentian tradition appear to be oriented to

the central uplands region. This has been interpreted as suggesting a primarily interior, riverine adaptation

(Dincauze 1974; Ritchie 1971).

Despite recent revisions about the diagnostic value of Small Stemmed projectile point types, the Small

Stemmed tradition continues to be an accepted Late Archaic cultural affiliation, although the duration

of the tradition has been extended into the Woodland Period in some areas (Mahlstedt 1985; Rainey

and Cox 1995; Wamsley 1984). This tradition may be a regional development out of the Middle

Archaic Neville/Stark/Merrimack sequence (Dincauze 1976; McBride 1984). Small Stemmed and

Small Triangular (Squibnocket) point types are characteristically associated with a quartz cobble

technological industry (McBride 1984) and with almost equal frequency quantitatively dominate both

artifact collections and excavated sites. Lamoka and Bare Island points are also associated with this

tradition. The Small Stemmed tradition exploited a wide range of ecozones including coastal and

riverine settings as well as upland areas.

The Susquehanna tradition has been most widely associated with mortuary/ceremonial sites in the

coastal zone of New England (Dincauze 1968b). Artifacts associated with this tradition consist of

Atlantic, Wayland Notched, Snook Kill, and Susquehanna Broad projectile points and several varieties

ofbifacial blades. Susquehanna tradition materials were manufactured from a variety oflithics including

local quartzite, eastem volcanic and exotic chert. This tradition and the Small Stemmed tradition

overlap into the Woodland Period.

Many of the projectile point styles attributed to these Late Archaic traditions were identified within the

Cutler B. Morse site collection, suggesting that the site was heavily used during the Late Archaic

Period. Site HB 1 contained a Brewerton-style projectile point (Edens 1994) and Small Stemmed points

were found at one or more sites on the perimeter of Silver Lake (Peters River drainage), as well as in an

isolated setting in Bellingham (Davin 1986).

The diversity of site locations and site types during the Late Archaic Period is documented by sites

located at estuaries (shell heaps, fishweirs, fishing camps), in the uplands (camps and workshops in the

PAL Report No. 1396.01

45

Chapter Four

Blue Hills), and by large base camps and ceremonial burials at the Watertown Arsenal. Several felsite

quarry and workshop sites have also been identified in the Blue Hills (19-NF-39, -40) as well as the

Hornfels-Braintree Slate quarries in Milton (19-NF-105, -106). Some ofthese quarries contained Late

Archaic materials. Late Archaic sites in the greater Boston area include Goat Acre and Spy Pond in

Arlington, the Spring Site in Medford, and several sites in Wakefield. The most notable of the Late

Archaic sites associated with fishing is the Boylston Street Fishweir (19-SU-16), which was discovered

in 1939 beneath 30 feet of fill at 501 Boylston Street during the construction of the New England

Mutual Life Insurance Company Building (Johnson 1949).

Similar intact fishweir stakes and/or wattle have been discovered at other locations in the Back Bay,

including: under Boylston Street proper during the 1903 construction ofthe Green Line Subway (Shimer

1918, Willoughby 1927); in 1949 during construction of the Old John Hancock Building (between

Stuart and Berkeley streets and St. James Avenue) (Johnson 1949); in 1960 during the construction of

the IBM Building (comer of Boylston and Clarenden Streets) (Kaye and Barghoom 1964); and most

recently, in 1986-1987 during the construction of 500 Boylston Street (Decima and Dincauze 1998).

The accompanying sediments for the 1986-1987 investigations provided the first systematic examination

of the fishweirs since the development of radiocarbon dating (Dincauze and Decima 1998; Kaplan et

al. 1990; Newby and Webb 1994; Rosen et al. 1993).

All of these investigations in which weir remains were recovered involved sites in the southeastem paJ.t

of the Back Bay. They are also all located within 1,000 ft of the 1630 shoreline in what has been

reconstructed to be an intertidal zone in a protected bend in the shoreline south of the nOltheasterly

bend of the original Charles River channel. The archaeological investigations of these sites resulted in

the discovery of weir stakes that were driven veltically into marine clay deposits and evidence of a

brush and twig wattle that was horizontally woven between the stakes. Extensive environn1ental analysis

accompanied the larger ofthese studies, and based on the results, it is possible to predict the stratigraphic

location of weir deposits in the lower pOltions of a deep layer of silt and silty clays that overlay the

Boston Blue Clay.

Recent carbon dating of weir stakes, orgaJ.1ics associated with sediments, and biostratigraphic pollen

ages have led Newby and Webb (1994) to aJ.·gue that the fishweir was in use between 4700 and 3700

B.P. Decima and Dincauze (1998) argue that the weir was in use for close to 1,500 years, between 5300

and 3700-3500 RP. The unique historical development (filling) ofthe Back Bay as a planned nineteenth­

century development has preserved the rich organic matter associated with these fishweirs. The thick

mantle of sand and gravel fill above the water table has allowed for the excellent integrity ofthe fishweir

orgaJ.1ic remains; although there is some evidence that nineteenth-century construction (i.e. pilings)

could have destroyed small weir structures (Mrozowski et al. 1999, 2000).

Transitional Archaic Period (3600-2500 B.P.)

The Transitional Archaic Period marks the interim between the Archaic and Woodland periods, and

represents a time of changing cultural dynamics. An extensive trade network, increased burial

ceremonialism, and the development oftechnologies strikingly different from those ofthe Late Archaic

characterize this period. Susquehanna tradition sites mark this period and aJ.·e best known :fi.-om cremation

cemetely complexes (Dincauze 1968b; Leveillee 1998). Altifacts diagnostic ofthis time period include

46

PAL Report No. 1396.01

Pre-Contact and Contact Period Cultural Context

Genessee, NOlmanskill, Wayland Notched, and Orient Fishtail projectile points as well as the presence

of steatite (soapstone).

The Orient Phase of the Transitional Archaic Period is regionally represented at quarry sites and

rockshelters. The quarrying of steatite and the manufacture of steatite vessels is an important

technological development associated with this tradition. Carved steatite vessels, prominent in this

period, reflect increased sedentism because ofthe low transportability ofthese items. Regionally available

steatite outcrops include the Dolly Bond Quany, the Home Hill Quarry, the Torrey Lane Site, and

others located in western Massachusetts and northern Rhode Island. The three quany sites yielded

Orient projectile points during excavation (Fowler 1966).

Steatite vessel fonTIs, such as bowls and later smoking pipes, were used domestically, ceremonially,

and as trade items. A distinctive lithic flaking technology and a new class of diagnostic tool forms also

developed. These new fonns either developed out of the local populations or were introduced to the

region by new groups immigrating into the New England area. Susquehanna tradition artifacts were

commonly manufactured from a variety of lithic materials including quartzite, eastern volcanics, and

non-local chert. Projectile points and tools ofthe Susquehanna are found commonly on multicomponent

sites and are often in association with Small Stemmed tradition materials (although not in mortuary

settings).

Burial ceremonialism also increased dramatically during tIns period as illustrated by the complex red

ochre internments at the Wateliown Arsenal and the complex mortumy ritual seen at the Millbury III

Site in Millbury. Grooved axes, clUcifonn drills, pestles, a copper blade, and Susquehanna and Wateliown

variety projectile points were all included in the Millbury ill burials (Leveillee 1998). Several radiocarbon

dates ranging from 3985 ± 145 to 1460 ± 90 B.P. were obtained from approximately 26 features/

deposits. The Millbury III radiocarbon data have been interpreted as representing multiple depositional

episodes spanning numerous generations that reflect a continuity of ideology transferred and reinforced

through ceremorualism (Leveillee 1998).

Cremation burials are also repOlied from the Wateliown Arsenal Site in Watertown, the Mansion Inn

and Vincent sites in Middlesex County, and the Cobum Site in East Orleans to nan1e a few (Dincauze

1968). Susquehanna Tradition points have been found in the upper Charles River drainage at one or

more sites on the perimeter of Silver Lake (Peters River drainage), as well as in Bellingham (Davin

1986). Other Susquehanna tradition sites in the BellinghmTI area include a broadspear point from

Locus 2 of the East Terrace Site as well as Locus 2 of the West Terrace Site that represents a lithic work

station (Waller and Leveillee 1998). Other notable Transitional Archaic sites in the greater Boston area

include the Spring Brook Site in the Arnold Arboretum (Pendery and Griswold 1993) and the Water

Street Site, a Susquehanna Tradition site identified in Charlestown during the archaeological

investigations of the nOlihern Central Artery (PendelY et al. 1982).

Early Woodland Period (3000-1600 B.P.)

The Early Woodland Period is generally underrepresented in the regional archaeological record of

southern New England. Some archaeologists have suggested that a population decline occurred in the

region during this period associated with any number of causal factors including unfavorable

PAL Report No. 1396.01

47

Chapter Four

environmental conditions and unknown epidemics (Dincauze 1974; Fiede12000; Lavin 1988; Mulholland

1988; Snow 1981; Wendland and Bryson 1974). However, the low representation may be more of a

function of a lack ofrecognition ofEarly Woodland cultural material components because ofoverlapping

(Susquehanna and Small Stemmed) and/or poorly documented tool assemblages. Given the problems

inherent in using one artifact type alone as a temporal indicator, the presence of early ceramics in

conjunction with point types is used to detelmine Early Woodland Period occupation in the absence of

radiocarbon dates.

Coastal resources are believed to have become an important part of subsistence collecting activities

and diets, as evidenced by the high frequency of known Woodland Period coastal sites in New England

(Cox 1983; Cox et al. 1983; Kerber 1983; Thorbahn and Cox 1988). This is also believed to be a time

of widespread long-distance exchange of raw materials, finished products, and infOlmation (MHC

1984). There is some evidence for the appearance of task-specific sites (Dincauze 1976). The Early

Woodland Period is marked by the clear emergence of ceramic technology, known as Vinette I, replacing

the soapstone vessels that had been used during the Late/Transitional Archaic periods. Diagnostic

materials include stemmed and side-notched Adena, Lagoon, Rossville, and Meadowood projectile

points. Artifact assemblages for this period comprise a high percentage of exotic lithic materials and

speak to an expansion and elaboration of long-distance trade networks.

Known Woodland Period sites in the Charles River drainage are limited in number. Early Woodland

artifacts were included in the Caterina collection from Beaver Pond, but comprised only a limited

sample (Strauss 1990). Fm1hermore, early pottery and an associated radiocarbon age of 2000 ± 75

years B.P. for Locus 1 of the East Terrace Site supports and Early/Middle Woodland presence in

Bellingham in the upper Charles River drainage (Waller and Leveillee 1998).

Middle Woodland Period (1650-1000 B.P.)

The Middle Woodland Period apparently saw increasing population and extensive long-distance social

and economic interaction. Larger base camps in riverine and coastal settings were established in

conjunction with ever-increasing sedentism. This is supp0l1ed by increased instances of storage pit

features suggesting production of bulky foods. The Middle Woodland Period is marked by the

introduction of h0l1iculture into the traditional hunting and gathering subsistence practices of human

populations in the Northeast. Horticulture led to changes in subsistence, population growth, organization

of labor, and social stratification (Snow 1980). The degree of dependence on h0l1iculture and its

significance as a stimulus of social and economic change in the late prehistory of southem New England

is still a topic for further archaeological research (Mrozowski 1993).

It has been suggested that changes in settlement and subsistence strategies during the Middle/Late

Woodland transition may have occurred independently of the adoption of horticulture (McBride and

Dewar 1987). Recent studies have shown that late Middle Woodland components are marked by a high

percentage of exotic lithics. Diagnostic Fox Creek and Jack's Reef projectile points are found in

association with Pennsylvania jasper, assorted New York State che11s, Ramah chert (Labrador), Kineo

felsite (Maine), and Lockatong argillite (northem Mid-Atlantic region) (Goodby 1988; Luedtke 1988;

Mahlstedt 1985). This assemblage of exotic raw materials suggest that Middle Woodland populations

inhabiting southem New England took part in an extensive network of social and economic contacts

48

PAL Report No. 1396.01

Pre-Contact and Contact Period Cultural Context

that extended from Pennsylvania northward to Labrador. Pottery also becomes increasingly stylistically

diverse, including grit-tempered coil built vessels with stamped, incised, and dentate decoration of

varying quality.

Middle Woodland settlement in the northem Boston Basin appears to have been concentrated at the

large estuary head and pond sites along the Charles and Mystic Rivers. Upper Charles River drainage

sites include the H-l Site and Blue Flag Site. The H-l Site contained chert,jasper, and hornfels chipping

debris and at least two radiocarbon-dated features dating to the Middle Woodland Period. The Blue

Flag Site along the upper Charles River in Bellingham produced a concentration of hornfels chipping

debris and an associated radiocarbon age of2000 ± 70 years B.P. of Middle Woodland origin (Rainey et

al. 1998). Fox Creek and Jack's Reef projectile points are also documented in the Cutler-Morse Site

artifact assemblage.

Late Woodland Period (1000-450 B.P.)

The Late Woodland Period is marked by an increase in ceramic production t1u'ough improvements in

technology. Some populations may still have relied solely on hunting and gathering while others tumed

to horticulture. Coastal areas and large semipermanent village settlements adjacent to arable lands,

particularly along broad floodplains, seemed to have been preferred. Farming, however, did not preclude

the continuance of seasonal rounds, and small task-specific camps are still common during this period.

Larger groups sometimes lived in fortified villages, indicating the presence of complicated political

alliances (Mulholland 1988). Late Woodland Period artifacts represented in the archaeological record

include triangular Levanna and Madison points, cord-wrapped, stick-impressed, and incised collared

ceramic vessels, and increasing amounts of local lithic materials (MHC 1984). This reliance on locally

available lithic materials suggests the formation of ancestral tribal territories that were noted as the

resident Native American tribes at the time of European contact.

The Late Woodland Period is well represented along coastal Massachusetts and along interior river

systems such as the Charles River. Site locations during this period show an increasing use of coastal

resources with high densities of sites located at river estuaries. Boston Harbor is an area known to

contain a high density of Late Woodland sites (Dincauze 1973). Large settlements, possibly base

camps occupied in the spring and fall, were located at estuary head sites like those on the Mystic and

Charles rivers (Dincauze 1974). Late Woodland deposits have been recovered from Arlington,

Watertown, Medford, Wakefield, Cambridge, Quincy, Chelsea, Milton, Newton, and surrounding towns.

In Boston proper, a Levanna-like projectile point was recovered from Boston Common near the Park

Street Station (Pendery 1988). Additionally, Levanna-type projectile points have been found in the

Cutler B. Morse Site and were included in the Caterina Collection from Beaver Pond.

Contact Period (450-300 B.P';A.D. 1500-1620)

The traditional cultural systems ofNative Americans were rapidly transformed during the contact period.

Contact with European populations slowly but completely disrupted Native American lifeways including

their social, economic, and political culture. The lifeways of the Native populations during this period

are believed to have been similar to those of the Late Woodland Period. There were a number of large

pem1anent base camps and villages, some fortified, as well as smaller satellite hunting and fishing

PAL Report No. 1396.01

49

Chapter Four

camps. Large groups may have gathered together at certain times of the year for resource exploitation

as well as for social and ceremonial functions.

Early ethnohistorical documents and modem ethnohistorical sources attest to the extensive trade network

in place during this period (Bragdon 1996; Brasser 1978; Snow 1980; Winthrop 1996). Fur trade was

an important economic factor for Europeans and Natives alike, and in return for furs the Native Americans

received clothing, food items, metal, and beads. Interaction between Native people and Europeans is

recorded in notes and writings of several early explorers and settlers including John Winthrop, William

Bradford, Thomas Morton, Samuel Champlain, and Samuel and Jolm Smith. European trade goods

were circulating to Native New England cultures especially during the early seventeenth century.

Although pre-contact period trade routes may not have continued in use throughout the terminal Late

Woodland (McBride and Dewar 1987), they were clearly serving as conduits for the distribution of

European goods, especially marine shell beads (wampum), by the early seventeenth centmy.

Disease and warfare decimated populations and dispersed survivors throughout the region. A major

epidemic occuned from 1616-1617 that drastically reduced Native populations. Smallpox and measles

in particular, had a drastic effect on the Massachusetts Native Americans. In the early 1630s, smallpox

almost annihilated the Native population around Boston Bay, although many in the interior survived to

help fOlm the villages of"Praying Indians" that existed from many years at Natick, Nonantum, Punkapog,

Hassanamesitt, and Magunco to the south and west of Boston (Cook 1976). The declining number of

Massachusett Native Americans was suggested by Gookin (1972), who said that "there are not of this

people left at this day above 300 men, besides women and children."

King Philip's War (1675-1676) resulted in the military defeat and geographic dispersal ofNative groups

in southem New England, particularly the Pokanoket and Nanagansett, as well as the virtual destruction

ofEuropean allies, including the Christianized Nipmuck "Praying Indians." Similar conflicts in nOlthem

New England continued well into the eighteenth century, with similar results. By the mid 1600s there

were few Native people alive in the region. This does not imply however, that New England's Native

peoples were "wiped out" during or after the period, or that they "lost" their cultures. Native Americans

continue to maintain distinct cultural traditions from the contact period to the present.

During the contact period the upper Charles River formed a border area for the Nipmuck and

Massachusetts Indian tribes. The Neponset and Weymouth river drainages fOlmed a border area between

the Massachusetts and Wampanoag tribes. Two Native Massachusetts core areas have been identified

in the greater Boston area: the Mystic core area to the north and the Neponset core area to the south

(MHC 1982b), with the Charles River serving as a likely boundary between the two. The core area of

settlement centered on the Mystic River estuary, and this core area also probably included several

smaller adjacent coastal drainages such as the Maiden, Pines, and Saugus Rivers. The larger lakes and

ponds, including Fresh Pond, nearby Spy Pond, Spot Pond, and Crystal Lake to the north, formed palt

of the inland section ofthe Mystic Core (MHC 1982b). In this core area, a major Native American trail

system probably followed the Mystic River north toward the adjacent Ipswich River drainage, with

smaller trails or paths along tributary stream networks (Figure 4-1). A number of secondmy trails are

believed to have existed along Washington and Boylston streets, and there was a fording place on the

Charles River at Wateltown Square (MHC 1982b). There were also transpOltation conidors in the

Back Bay area near Dudley, Roxbury, and Tremont streets, and Huntington Avenue.

50

PAL Report No. 1396.01

Pre-Contact and Contact Period Cultural Context

The Mystic River core area had its

own sachem, Nanepashemet, and

reportedly contained several

settlements protected with palisade

and ditch systems (Barber 1839).

Nanepashemet was killed at one of

these "forts" in 1619 by a raiding

Tanentine group from coastal Maine.

Leadership of the groups in this core

area passed to Nanepashemet's

widow.

W Fishing Weir

= Major Fords

..rTrails

The Native American Place name

Menotomet was associated with the

area between Alewife Brook and the

Mystic River in Arlington (MHC

1981 a). Fishweirs were most likely

°00

o

located at several points along

Alewife Brook during the contact

period based on later descriptions in

English documents. A significant area

of settlement was probably located

around the Alewife Brook/Mystic

River confluence. A group of contact

period burials were accidentally

uncovered in West Medford in the late

nineteenth century on the east side of

the Mystic River. Cemeteries with Figure 4-1. Contact period Native American trails with the

contact period burials are also known approximate location of the Urban Ring Corridor.

to have existed in the Revere Beach

and Nahant sections of the Mystic core area (Dincauze 1974).

To date, the only contact period sites in the City of Boston are those associated with burials. One such

burial at Union Market Station included projectile points made of copper. A second site in the Savin

Hill area contained burials and associated grave goods including glass beads, metal projectile points,

and pieces of fiber-woven material. Several unverified contact sites, primarily noted in historic

documents, also exist in the area and include a palisaded fort at Brookline Village and a site at Bunker

Hill Community College on the nOlih bank of the Charles River near Cambridge Street.

Known and Expected Native American Resources

The majority of known Native American sites dating to the pre-contact and contact periods in the

vicinity of the Urban Ring project conidor have been identified through avocational recorded and

investigated site locations. A review of the MHC site files revealed that most of the known Native

American sites in the Boston Basin, and specifically in the vicinity of the project area, are located in

PAL Report No. 1396.01

51

Chapter Four

close proximity to coastal zone estuarine environments, major rivers, and ponds. The distribution of

known sites indicates that core areas of Native American settlement/subsistence activity were located

near the major rivers (Mystic, Charles, Saugus) entering Boston Harbor and adjacent sections of the

coastal zone. Other areas of concentrated settlement were on the margins of large ponds. Some large

sites in these core areas contain evidence of recun'ent occupation over thousands of years.

In general, for those sections of Middlesex and Suffolk counties traversed by the Urban Ring corridor,

sites for the entire pre-contact period were most likely present at one time, but have been destroyed by

the constant development and increasing occupation of these seven communities since the seventeenth

centmy. All that remained ofthose sites have been documented primarily by the MAS. No evidence of

PaleoIndian Period activity has been found to date in the immediate project vicinity. Early Archaic

Period occupations are also scarce.

MHC site forms from the Middle to Late Archaic Period do exist for Middlesex County (l9-MD-627,

19-MD-371, 19-MD-269, 19-5U-29, 19-5U-77 19-MD-171). Most of these have been found in

Cambridge, and one in Somerville. The greatest number of sites for Late Archaic depositions is in

estuarine and coastal areas. This pattern likely reflects the stabilization ofcoastlines and the development

of shellfish beds.

Woodland Period settlement and land use patterns in central Massachusetts are marked by a general

shift from principally riverine site locations to the coastal plain. Woodland Period sites have also been

found in both Suffolk and Middlesex counties (l9-MD-364, 19-5U-48, 19-5U-59, 19-5U-80). A shell

midden site was reported in the nineteenth century on Lechmere's Point (l9-MD-17l). The site file

lists the period as "unknown," but this shell midden could likely be a Woodland site.

A contact period site (l9-SU-44) has been recorded in the Charlestown neighborhood of Boston.

Additionally, the enviromnental diversity of the greater Boston coastal zone would have suppOlied a

sizeable population. The introduction of hOliiculture into the Late Woodland and contact economies

most likely prompted local populations to exploit the area's agriculturally suited land. Subsistence

activities would have been amply supplemented with excellent fishing potential as well as interior

hunting of small animals.

Table 4-2 presents the inventory of recorded Native American archaeological sites within the Urban

Ring project corridor and the immediate vicinity.

52

PAL Report No. 1396.01

Pre-Contact and Contact Period Cultural Context

Table 4-2. Known Native American Archaeological Sites Within and in the Vicinity of the Urban

Ring Phase 2 Project.

MHC

Site Name

Temporal Period

Location

No.

I

19-5U­

Summit Site, Savin Hill

Unknown

Boston (Dorchester)

18

I

19-5U­

Contact Period Village

Contact

Boston (Charlestown)

44*

I

19-5U ­

Unnamed

Unknown

Boston (Dorchester)

46

19-5 UChelsea Water Street

Woodland

Boston (Charlestown)

48

19-5U­

Town Dock Pottery Site

Woodland

Boston (Charlestown)

59

Dillaway-Thomas Site

Middle-Late

19-5U ­

Boston (Roxbury)

77

Archaic

19-5 U­ I Hog Bridge Fish Weir

Late Woodland

Boston (Roxbury)

80

/Contact

19-5 UStoney Brook I

Unknown

Boston (Roxbury)

81*

19-5U ­

Meetinghouse Hill

Unknown

Boston (Roxbury)

96

19-MDLechm ere Point Shellheap I poss. Late Archaic

Cambridge

171*

/W oodland

19-MD­ I Magazine Beach

Cambridge

I Unknown

172

19-MDUnnamed

Cambridge

I Unknown

173*

19-MDUnnamed

Unknown

Medford

367

Source: MHC site files

* indicates site within the alignment of one of the four alternatives

County

I

Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk

Middlesex

Middlesex

Middlesex

Middlesex

PAL Report No. 1396.01

53