Playgrounds and Prejudice: Elementary School Climate in the United States

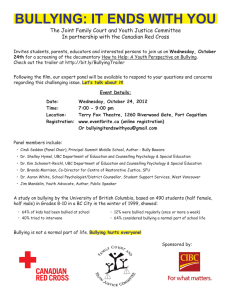

advertisement