Document 13037305

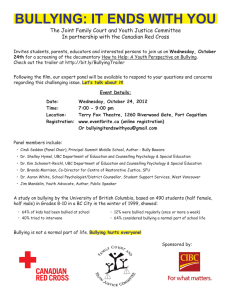

advertisement