Gresham’s Ghost: Challenges to Written Culture

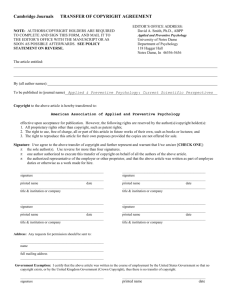

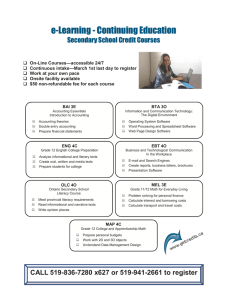

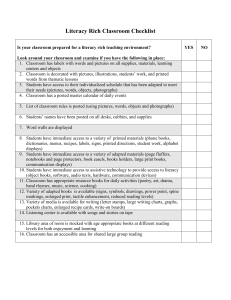

advertisement