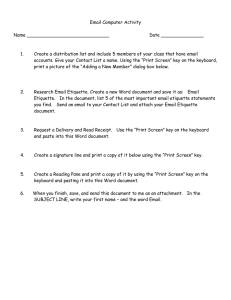

Who Sets Email Style?

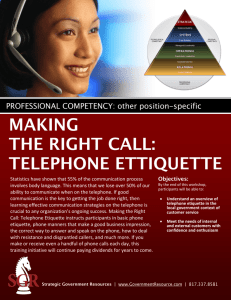

advertisement