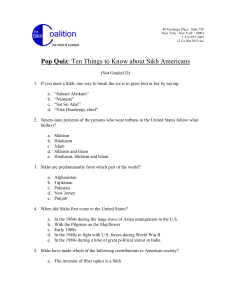

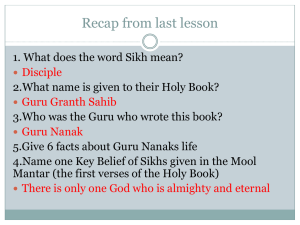

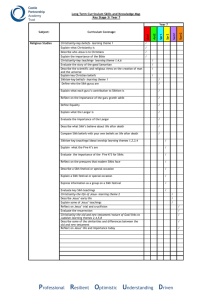

Religious, Moral and Philosophical Studies Morality in the Modern World: Sikhism

advertisement