The University of Notre Dame

advertisement

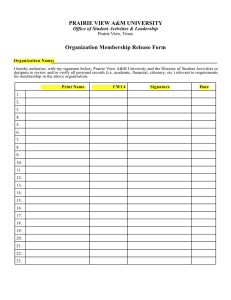

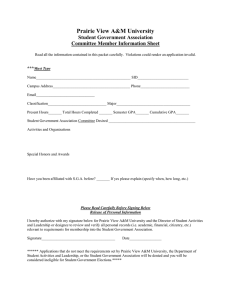

The University of Notre Dame Response of Raptors to Reduction of a Gunnison's Prairie Dog Population by Plague Author(s): Jack F. Cully, Jr. Source: American Midland Naturalist, Vol. 125, No. 1 (Jan., 1991), pp. 140-149 Published by: The University of Notre Dame Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2426377 . Accessed: 27/05/2011 12:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=notredame. . Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. The University of Notre Dame is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Midland Naturalist. http://www.jstor.org Am.Midl. Nat. 125:140-149 Response of Raptors to Reduction of a Gunnison's Prairie Dog Population by Plague JACK F. CULLY, JR.' ofNew Mexico,Albuquerque87131 Museum ofSouthwestBiology,Dept. ofBiology,University ABSTRACT.-Raptors were counted at approximately2-week intervalsbetween March and November1985-1987in theMorenoValley,ColfaxCo., New Mexico.Duringthat thevalleyand sequentially pestis)sweptthrough period,an epizooticof plague(Yersinia 25 km2 in threeareasofapproximately gunnisoni) killedGunnison'sprairiedogs(Cynomys overthe each. Red-tailedhawk (Buteojamaicensis)numbersdid notchangesignificantly theirnumdeclinedin abundance, goldeneagles(Aquilachrysaetos) studyperiod.Although hawks(B. regalis) ofprairiedogsin 1987.Ferruginous withtherecovery bersdidnotrecover whereprairiedogswere abundant,but their were abundantduringautumnmigration prairie declineofprairiedogs.Gunnison's withthepopulation significantly declined numbers forferruginous hawksduringtheirmigration foodresource dogsappearedtobe an important theMorenoValley. through INTRODUCTION The importanceof large rodentsand lagomorphsas preyformanyraptorspecies during and Murphy, thebreedingseason is well documented(Howard and Wolfe,1976; Woffinden 1977, 1989; Janes, 1985; Bednarz, 1987; Schmutzand Hungle, 1989). There is less information on the diet of raptors during migrationand winter,despite the fact that raptor mortalityin the nonbreedingseason may be high and may affectpopulationstability(Hall et al., 1988; but see Schmutzand Fyfe,1987; Cully, 1988). Between 1985-1987 an epizootic of plague (Yersinia pestis) reduced numbersof Gunnison's prairie dogs (Cynomys gunnisoni) in the Moreno Valley, New Mexico, 105?16'W, 36030'N, (Cully, 1988, 1989). This eventprovidedan opportunityto studythe numerical relationshipbetweenprairie dogs and migratoryraptors.The plague outbreakconstituted a serendipitous"natural experiment"in thatthe epizooticprogressedthroughthreephases fromthe northend of the valley to the south,and decimatedprairie dogs over threelarge discreteareas. This paper describeschangesin raptorabundance in each area thatoccurred as the preyresourcedeclinedand then recovered. If prairie dogs regulatelocal raptorpopulationsin the Moreno Valley, then dependent raptorpopulationsshoulddecreasein thesame areas ofthevalleywhereprairiedog numbers declined.Dependentraptorpopulationsshouldthenincreaseas prairiedog numbersrebound followingtheepidemic.Small changesin prairiedog densitymightnotaffectraptornumbers if the raptor populations are held below the carryingcapacity of the prey base by other extrinsicfactors.However, even it the raptorswere below carryingcapacitypriorto plague, but dependenton prairie dogs, the near total eliminationof prairiedogs by plague should be followedby statisticallydetectablereductionsin raptor numbers.Response of raptor numbersto changingprairiedog numberswould not occur if raptornumbersare regulated by factorsotherthan prairie dog abundance, or if raptor species forageopportunistically I Presentaddress:VectorBiologyLaboratory, of of BiologicalSciences,University Department NotreDame, NotreDame, IN 46556 140 1991 CULLY: RAPTORS AND PRAIRIE DOG PLAGUE 141 by switchingfromone preyspeciesto anotherdependingon the relativeabundance ofother preyspecies. If raptorsrespondto reducedprairie dog numbersby movingelsewhere,this would also be recordedas a local decline in raptorpopulation. METHODS Raptor counts.-I conducted43 roadside counts of raptors (excluding turkeyvultures, Cathartesaura), at intervalsof approximatelytwo weeks fromMarch 1985 to November 1987. Counts were made on morningswith winds less than 20 KPH and usually began between09:00 and 10:00 MDT. The surveyroutewas the same in all cases, was approximately30 km long and took 2-2.5 hours to complete(Fig. 1). I stoppedat approximately 1-kmintervalsto scan forraptors.On mostmornings,at moststops,no raptorswere counted. If a raptorappeared betweenregular stops,I pulled offthe road to identifyit and record its location. I was carefulnot to count a raptor more than once. These counts probably underestimatedthe total number of raptors presentin the valley, but procedureswere standardizedto provideaccuraterelativeestimatesofraptordensity.The speciesand location of each raptorwas noted so that it could be assigned to one of threeareas (north,middle, south) withinthe valley. Raptors seen in each sectionof the valley were thentabulatedby species. -Two studysiteswereestablishedin theMoreno Studysitesand estimation ofpreynumbers. Valley prior to the plague epizooticto monitorprairie dog numbers.The Midlake study site was establishedadjacent to Eagle Nest Lake in October 1984, and the Val Verde site was establishedin October 1985 (Fig. 1). In October 1984, I droveor walked throughall suitable habitat east of Highway 64 to determinethe distributionof prairie dogs in the valley. I estimatedthat 40% of the grasslandhabitatwas populated by Gunnison's prairie dogs, and thatthe densityat Midlake was typicalof coloniesgenerallyin 1984, and in the middleand souththirdsofthevalleyin July1985. Prairiedog densityand colonydistribution west of Highway 64 appeared to be similarto that east of the highway. I establishednew studyareas at two additionaltownsto monitorprairiedog population recoverysubsequentto plague. Vega was establishedin the northin April 1986 following the epizooticin 1985 (Fig. 1). South Entrancewas establishedin May 1987 followingthe epizooticin the middle of the valley. Val Verde, like Midlake, was monitoredbeforethe epizooticand, because some prairie dogs survived,monitoringcontinuedafterwardsas well. Afterplague passed througheach area, I searchedthe plague-affectedareas forsurvivingprairie dogs. In addition,in areas throughwhich the plague had passed, I recordedany prairie dogs observedduringraptor surveys.When I foundnew colonies I estimatedthe area of the colonyand the numberof prairie dogs. At Midlake I staked a 6 ha grid,and at Vega and South Entrance I staked 2 ha grids to map burrows.I attemptedto trap and markall prairiedogs in the markedareas in order to obtain estimatesof population size. Prairie dogs were live-trappedand marked with numberedear-tagsand dye marks in the fur. Population size was estimatedat each area, each yearby dividingthetotalnumberofindividualscaughtand markedbythearea trapped and then multiplyingthe estimatedarea of the colonyby the estimateddensity.I did not mark a grid or map burrowsat Val Verde, but trapped prairiedogs on approximately0.5 ha in 1985 and 1 ha in 1987. The populationof the studysite colonieswas thenused as a relativeindex of prairiedog populationin the north,middleand southsectionsofthevalley. Because there were numerous prairie dog colonies in each sectionof the valley prior to plague, but the study colonies were the largest of a reduced number of colonies in each 142 THE AMERICANMIDLAND NATURALIST 125(l) ....... .2~~~~~~~......... ~~4~A ~~ u 64 yareno...*-rCr-* JIc,efl ~ VEA S A A ML A 4 p<NM 0. 38 Raptor Survey Sites KM_____ Raptor Survey Route Trap Site -Paved C 1 2 3 Roads Dirt Roads 0 LIForestf FIG. 1.-Map of MorenoValleyshowingthelocationof theraptorcensusroute,and theareas affected VV = Val by plagueeach year.The trapsitesare ML = Midlake,SE = SouthEntrance, Verde,and Vega. The heavylines (1) and (2) dividethe valleyintothe threesectionsaffected sequentially byplague:northin winter1984-1985,middlein summerand autumn1985 and south duringsummer1986 region afterthe plague, the population declines that occurredas a resultof plague were greatlyunderestimatedby the trappingcounts. Analysis. -Although otherraptorspecies were seen duringcounts,threespecies,the redtailed hawk (Buteoj'amaicensis),ferruginoushawk (B. regalis), and golden eagle (Aquila were presentin high enough numbersforstatisticalanalysisduringthe period chrysaetos), when prairiedogs were active.Numbersofred-tailedhawks,ferruginous hawks,and golden eagles were subjectedto a two-wayanalysisof variance(ANOVA), using SPSSPC + (Noofdata to equalize variances(Sokal and Rohlf, rusis,1988) afterlogarithmictransformation 1981). The treatmenteffectsof theANOVA were area (north,middleand south)and year. If raptorabundance is a functionof prairiedog abundance, as hypothesized,the ANOVA should have a significantinteractioneffectbecause the northand south had high prairie dog densitiesin different years. To testwhethersignificantinteractionpatternscorrelate with prairie dog density,hawk densityand prairiedog densitywere testedforcongruency by use ofa Spearman's rankcorrelationtestusing SYSTAT (Wilkinson,1989). The prairie dog densitiescalculated fromtrappingdata were not independentbetweencountswithin years,however,so statisticalsignificanceshould not be attributedto this test.In all other statisticalanalyses the alpha level was set at 0.05. 1991 CULLY: 143 RAPTORS AND PRAIRIE DOG PLAGUE TABLE1.-Prairie dogdensity estimates basedon thenumberofindividualprairiedogscaptured at thefourstudysites.The plagueepizootics occurred in winter/spring 1985 at Vega,summer/fall 1985 at Midlakeand SouthEntrance, and summer1986 at Val Verde Date Number trapped Area trapped Oct. 1984 July1985 1.5 ha 6.0 ha S. Entrance Sept. 1985 May 1986 Sept. 1987 Oct. 1987 45 168 Val Verde Oct. 1985 13 Site Midlake Vega 25 7 0 19 July 19863 Aug. 19864 Aug. 1987 30 18 4 6.0 ha 6.0 ha 1.0 ha 2.0 ha 0.5 ha 1.0 ha 1.0 ha 2.0 ha May 1986 Oct. 1986 Oct. 1987 17 69 116 2.0 ha 2.0 ha 2.5 ha Density perha 30 28 4.1 1.2 0 Colonyarea' Colonypop. 100 ha 100 ha 9.5 262 30 18 2.0 100 ha 100 ha 0 ha 3 ha 200 ha 200 ha 5 ha 10 ha 8.5 34.5 46.4 2 ha 2 ha 5 ha 3,000 2,800 410 120 0 28 5,200 6,000 90 20 17 69 232 I Estimated fromU.S. Geological Survey Maps 2 In October-November 1985,adultfemalesand mostyoungwerealreadyhibernating. See text 3July 1986,beforeplague 4September 1986,following plagueepizootic RESULTS Prairie dog populations. -Based on visual observationsof fur-markedindividuals,more than 90% of the prairie dogs on the 6-ha study site at Midlake were captured between October 1984 and July 1985. In October 1984, the prairiedog densityat Midlake was 30/ ha (Table 1). I estimatedthat prairiedog coloniesoccupied a total area of 40-50 kiM2,and that the total prairie dog population in the Moreno Valley was 100,000-150,000 at that time. The Vega studysitewas notyetestablishedin 1984, but theprairiedog densityat colonies in the northappeared to be comparableto densityat Midlake. I estimatedthatprairiedog coloniesin the norththirdof the valley covered1000 ha in 1984, fora totalpopulationsize of 30,000. Plague struckthe prairie dogs in the northernthirdof the valley duringwinter and spring1985 (Fig. 1), and the prairiedog populationin the northdeclinedat thattime. A carefulsearchin June 1985 locatedisolatedindividualsand one colonyofabout 20 prairie dogs thathad disappeared one monthlater. There were scatteredprairiedogs in the north in late summer,but the population densitywas less than 1 per ha. A small colonyof 17 prairie dogs formedat Vega in spring 1986. The Vega colonygrew during 1986-1987 to morethan 200 prairiedogs by October 1987 (Table 1). In 1987 therewere also othersmall colonies establishedin the north. On 15 July 1985, therewas no noticeabledecline in prairie dog densityin the middle sectionof the valley. However, by mid-September1985, the populationwas in decline and I was able to countonly 25 prairie dogs on 6 ha at Midlake. All were gone fromMidlake by July 1986 (Table 1). By 1 September1986, I was able to locate only 2 prairiedogs in a carefulsearch of 2 km2adjacent to Eagle Nest Lake. Based on visual searches,the total THE 144 AMERICAN MIDLAND 125(1) NATURALIST hawksandgoldeneaglesthroughout ofred-tailed hawks,ferruginous TABLE2.-Seasonal abundance (Summer),and theentirevalleyandoverall threeyears(1985-1987)on countspriorto 1 September foreach raptor are shownseparately (Autumn).Means and standarddeviations after1 September speciesin each area in Figure2. n = thenumberofraptorcounts,x = themeannumberand SD iS between thestandarddeviationofhawksper count.F is theresultofANOVA testsfordifferences seasons Speciesandseason n S SD F P Red-tailedhawks Summer Autumn 30 13 1.90 7.69 1.71 5.19 30.62 <0.0001 30 13 0.43 6.23 0.82 5.26 35.54 <0.0001 30 13 1.47 1.69 1.59 1.87 hawks Ferruginous Summer Autumn Goldeneagles Summer Autumn 0.157 0.694 prairiedog populationin themiddlesectionofthevalleydid notexceed 25 in October 1986. A small colonyat South Entrance increasedto approximately30 by October 1987. I estimatedthatmorethan 30,000 prairiedogs were presentat thesouthend ofthevalley (including Val Verde) in September 1985. In October and November 1985, afteradult femalesand mostjuvenile prairie dogs were hibernating,I captured 1 juvenile femaleand 12 adult male prairie dogs on 0.5 ha at Val Verde (Table 1). In July 1986, I trapped 30 prairiedogs thereon approximately1 ha, but the proportionofmarkedindividualsin traps did not exceed 50%, so my estimateof the population prior to plague at the Val Verde colony was too low (Table 1). This colony was destroyedby plague within the month followingtheJuly 1986 trappingsession. In August I trappedat an isolatedcolonynearby and estimatedthe population to consistof 90 prairie dogs. The epizootic spread to that colonyand throughoutthe southernarea in summer 1986 and by October 1986 the population in the southwas reducedto <100 prairiedogs. The epizooticcontinuedinto 1987, when 4 prairie dogs were captured on 2 ha at Val Verde (Table 1). In August 1987, I estimatedthattherewere 25-50 prairie dogs in the south thirdof the valley. Raptorpopulations.-Red-tailed hawks, ferruginoushawks and golden eagles were all commonspecies in the Moreno Valley during the threeyears of this study,and all were observedkillingprairie dogs (Cully, 1988). The red-tailedhawk was the most abundant species duringthe summerand theirnumbersincreasedduringautumn migration(Table 2). Golden eagles were also presenteach year duringspring,summerand autumn when prairiedogs were activeabove ground,but goldeneagle numbersdid not change seasonally (Table 2). Ferruginoushawks were most commonduringautumn migration.They were irregularand uncommonvisitorsduring springand summer.Prior to autumn migration, which began in September,the mean numberof all raptorsseen per 30-km countwas 6.8 (n = 30 counts,SD = 4.09). During the September-Octobermigrationperiod,the mean numberof raptorsper count increasedto 21.1 (n = 13 counts,SD = 7.84). throughout During bothsummerand autumnthered-tailedhawkswereevenlydistributed amongyearswas nearlysignificant(Table thevalley.The summerANOVA fordifferences CULLY: 1991 145 RAPTORS AND PRAIRIE DOG PLAGUE hawksand and autumnred-tailed TABLE 3.-Results ofANOVA ofareasand yearsforsummer hawks ferruginous Species/season Red-tailedhawks Summern = 30 Autumnn = 13 hawks Ferruginous Summern = 30 Autumnn = 13 Sourceofvariance df F P Overall 89 2 2 4 1.437 1.140 3.044 0.782 0.194 0.325 0.053 0.540 Overall 38 2 2 4 1.761 1.639 1.147 2.129 0.125 0.211 0.331 0.102 Area Year Interaction Area Year Interaction Inadequatenumbersforanalysis. 11.077 38 Overall Area Year Interaction 2 2 4 4.129 11.139 14.520 <0.001 0.026 <0.001 <0.001 3), but that statisticprobablyreflectsthe low numberof red-tailedhawks in the south in 1985 (Fig. 2) when prairiedogs were abundantthere.The interactiontermin theANOVA (r = -0.102) did not was not significant,and the Spearman rank correlationcoefficient indicatecorrelationof red-tailedhawk numberswith prairie dog abundance. Golden eagles were less commonduringall seasons than red-tailedhawks, and during autumn they were less commonthan ferruginoushawks. Golden eagle numbersdid not betweensummerand fall, so seasonal data were lumped foranalysis. change significantly They were most commonin the southerntwo-thirdsof the valley duringall 3 years (Fig. among areas (F = 8.923, n = 129, P < 2). Golden eagle numbersdifferedsignificantly 0.001) and years (F = 5.282, n = 129, P = 0.006), but the interactionwas not significant (F = 1.204, n = 129, P = 0.313). in the numbersof ferruginoushawks counted There were highlysignificantdifferences in summervs. autumn (Table 2). Prior to autumnmigration,ferruginoushawks were rare in theMoreno Valley withtwofewdata forstatisticalanalysis.The autumncounts,however, among years and areas, and the interactiontermwas showed highlysignificantdifferences also significantduring autumn (Table 3). During autumn migrationferruginoushawk numbersin the threesectionsof the valleywere positivelycorrelatedwithestimatedprairie = 0.658), although significancelevels dog density(Spearman rank correlationcoefficient cannotbe inferredas discussedabove. DISCUSSION to obtainbecause thesebirdstravelover Data on foodhabitsof large raptorsare difficult long distances.Bednarz (1988) followedgroups of radio-taggedHarris' hawks (Parabuteo uncinctus)duringtwo wintersand observed30 killsin 403 h ofobservation.Callopy (1983b) observed126 attackson preyby goldeneagles ofwhich 23 were successful.Otherfoodhabit studiesoflarge raptorshave focusedon preydeliveredto nests(Luttichetal., 1970; Wakely, 1978; Ensign, 1983; Callopy, 1983a; Gilmer and Stewart,1983; Janes, 1985; Steenhoffand THE 146 AMERICAN 125(1) NATURALIST MIDLAND Golden Eagle * North L Middle 5 Q) 4 - South 3 zE) C: d 2 Q) 1985 1987 1986 Autumn Summer Ferruginous Hawk 10 5 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~Q) 4. z E Oj 6 Qj 1985 1986 4 1985 1987 Red-taiiled 1986 1987 1986 1987 Hawk 10 504 Q)~~~~~~~~~~~~~~- 1985 1986 1987 1985 FIG. 2.-Number of raptorsseen on countsduring1985-1987. The histogramsrepresentthe mean number per count at the North, Middle, and South sectionsof the valley. The verticalbar is 1 SD. Note that the scale for autumn red-tailedhawks and ferruginoushawks is double that of summer. Golden eagle data are pooled forspring,summerand autumnbecause therewere no seasonal differences in numbers 1991 CULLY: RAPTORS AND PRAIRIE DOG PLAGUE 147 observations(Cully, 1988). Food habitdata formigratory Kochert,1988), or on opportunistic raptorsare virtuallynonexistentbecause of the transientbehaviorof the birds. to examine The plague epizooticin the Moreno Valley providedan unusual opportunity the relationshipbetweenraptorsand prairiedogs because ofthe dramatic,spatiallydefined, changes in prairie dog density.Prairie dog mortalitydue to plague exceeded 99% (Cully, in Gunnison'sprairiedogs caused byplague in Colorado 1989), and was similarto mortality (Lechleitneret al., 1962, 1968; Fitzgerald, 1970; Barnes, 1982; Rayor, 1985). The prey communitywas well suitedto thisanalysisbecause otherlarge rodentor rabbitpreyspecies groundsquirrels(Spermophiwere rarein thevalley.Gunnison'sprairiedogs,thirteen-lined meadow voles (Microtuspennsylvanicus)and deer mice (Peromyscus lus tridecimlineatus), maniculatus)were the available prey species in the grasslandwhich was the focusof this study.Botta's pocketgophers (Thomomysbottae)occurredlocally but were more common at the edge of the surroundingforestthan in grassland. During fouryears of fieldwork (approximately1500 h of observation)I saw only threecottontailrabbits(Sylvilagussp.), this species is also more commonat the forestedge, and one black-tailedjackrabbit(Lepus in the grassland.Woodrats (Neotomasp.), golden-mantledgroundsquirrels(S. californicus) lateralis)and least chipmunks(Eutamiasminimus)were commonin the surroundingforest, but absent fromthe grassland. Red-tailed hawks preyedon prairie dogs (Cully, 1988), but there was no statistically significantrelationshipbetweenred-tailedhawk numbersand spatial or temporalchanges in prairiedog numbers.Red-tailedhawks used alternatepreyspeciesin the Moreno Valley; groundsquirrelsonce each. In the valley I saw themkill meadow voles and thirteen-lined bottomhabitat,thisspecieswas mostfrequentlyseen associatedwithmesicgrasslandwhere voles were abundant. Red-tailed hawks were frequentlyseen flyingalong the forestedge, and theyprobablyalso took preythat occurredthere.Red-tailed hawks have a varied diet (Luttich et al., 1970; Janes, 1985), a featurethat probablyallowed themto persistin the Moreno Valley withoutspatial or temporalpopulationchanges despitethe radical fluctuations in the prairie dog populations. Golden eagles were oftenseen huntingoverprairiedog towns.They were also frequently observedat theforestedge,particularlyat the southend ofthevalley.Golden eagle numbers steadilydeclined throughoutthe valley from 1985-1987. Golden eagles probablyforage hawks so thatas longas preywere available overlargerareas than red-tailedor ferruginous somewherein the valley eagles could be foundat theirfavoredperchsitesat the southend ofthevalley.Golden eagles use large preyspeciessuch as black-tailedjackrabbits,mountain nuttaiji),prairiedogsand groundsquirrels(Callopy,1983a, b; MacLaren cottontails (Sylvilagus etal., 1988; Cully, 1988). At theSnake RiverBirdsofPreyArea, in Idaho, rabbitsconstituted more than 90% of prey deliveredto golden eagle nests(Callopy, 1983a), and in Wyoming 62%, prairiedogs 18% and groundsquirrels5% ofpreybiomassdelivered rabbitscontributed to golden eagle nests (MacLaren et al., 1988). When theyare available, prairie dogs are probablyimportantpreyforgoldeneagles in the Moreno Valley. Prairie dogs were missing fromthe northend of the valley when raptor counts began in 1985, and the low eagle numbersthen may reflectthe absence of prairie dogs. The steadydisappearanceof golden eagles from1985-1987 correlateswiththe demiseof prairiedogs thatresultedfromplague. Althoughtherewas some recoveryof prairie dogs in the northby spring1987, theremay have been too few prairie dogs at thattimeto supportnestingeagles. Ferruginoushawks were abundant during migration,were rare at other times of the year, and did not breed in the Moreno Valley. During autumn,when ferruginoushawks were abundant,theirspatial distributionwas consistentwith the hypothesisthat the local 148 THE AMERICAN MIDLAND NATURALIST 125(1) abundance of this species was linked to the availability of prairie dogs during autumn migrationin the Moreno Valley. Ferruginoushawks primarilytake large prey such as rabbits(Howard and Wolfe, 1976), groundsquirrels(Ensign, 1983; Gilmer and Stewart, 1983; Wakeley, 1978; Schmutz and Hungle, 1989) and Gunnison's prairie dogs. Unlike red-tailedhawks and golden eagles, which frequentlyhuntedalong the forestedge, ferruginous hawks were always seen huntingover grassland. During 1984-1985, I saw ferruginous hawks kill prairie dogs six times (Cully, 1988), and I never observedthe species withotherprey.The patternofferruginous hawk abundanceduringfallmigrationsuggested that ferruginoushawks respondedstronglyto the local availabilityof prairiedogs. -I am indebted Acknowledgments. toJamesBednarzwhoconducted raptorsurveys duringSeptemI am also grateful to berand October1987 and whoprovided hoursofdiscussion. manyinteresting andmanyhelpfulcomments AnneCully,GaryGrahamandJohnHubbardfortheirsupport throughto Mr. Les Davis and thelateBill Gallagherand hisfamily outthisproject.I am especially grateful forallowingme to workon theirranches.The manuscript benefited fromthecomments of Daniel This workwas supported reviewers. Witter, JosefK. Schmutzand anonymous bya grantfromthe New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, Share WithWildlifeProgram,and NIH National ResearchServiceAwardTrainingGrant2 T32 Al 07030. LITERATURE CITED BARNES,A. M. 1982. Surveillanceand controlof bubonic plague in the United States. Symp.Zool. Soc. Lond., 50:237-270. BEDNARZ,J. C. 1987. Successive nestingand autumnal breedingin the Harris' Hawk. Auk, 104: 85-96. 1988. Cooperative huntingin Harris' Hawks (Parabuteouncinctus).Science,239:15251527. CALLOPY,M. W. 1983a. A comparison of direct observationand collectionsof prey remains in determiningthe diet of golden eagles. J. Wildl.Manage., 47:360-368. 1983b. Foraging behaviorand success of golden eagles. Auk, 100:747-749. CULLY,J. F., JR. 1988. Gunnison's prairiedog: an importantautumnraptorpreyspeciesin northern New Mexico, p. 260-264. In: R. L. Glinski,B. G. Pendleton,M. B. Moss, M. N. LeFranc, Jr., B. A. Millsap and S. Hoffman(eds.). Proceedingsof the SouthwestRaptor Management Symposiumand Workshop. Nat. Wild. Fed. Sci. Tech. Series, No. 11, Washington. 1989. Plague in prairie dog ecosystems:importanceforblack-footedferretmanagement,p. 47-55. In: T. W. Clark and D. K. Hinkley (eds.). The prairie dog ecosystem:managing for ecological diversity.BLM Wildlife Tech. Bull., No. 2. ENSIGN,J. T. 1983. Nest site selection,productivityand food habits of ferruginoushawks in southeasternMontana. M.S. Thesis, Montana State University,Bozeman. 85 p. FITZGERALD,J. P. 1970. The ecologyof plague in prairie dogs and associated small mammals in South Park, Colorado. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Colorado State University,Fort Collins. 90 p. GILMER,D. S. ANDR. E. STEWART. 1983. Ferruginoushawk population and habitatuse in North Dakota. J. Wildl.Manage., 47:146-157. HALL, R. S., R. L. GLINSKI,D. H. ELLIS, J. M. RAMAKAAND D. L. BASE. 1988. Ferruginous hawk, p. 111-118. In: R. L. Glinski, B. G. Pendleton,M. B. Moss, M. N. LeFranc, Jr., B. A. Millsap and S. Hoffman(eds.). Proceedingsof the SouthwestRaptor Management Symposium and Workshop.National Wildlife FederationScientificand Technical Series No. 11, Washington. HOWARD,R. P. AND M. L. WOLFE. 1976. Range improvementpracticesand ferruginoushawks. J.Range Manage., 29:33-37. JANES,S. W. 1985. Influenceof territorycompositionand interspecificcompetitionon red-tailed hawk reproductivesuccess. Ecology,65:862-870. CULLY: 1991 RAPTORS AND PRAIRIE DOG PLAGUE 149 W. HUDSON. 1968. An epizootic of plague in Gunnison's prairie dogs (Cynomysgunnisoni)in southcentralColorado. Ecology, LECHLEITNER, R. R., L. KARTMAN, M. I. GOLDENBERG AND B. 49:734-743. J. V. TILESTON AND L. KARTMAN. 1962. Die-off of a Gunnison's prairie dog colony in centralColorado. ZoonosesRes., 1:185-199. LUTTICH, S., D. H. RUSCH, E. C. MESLOW AND L. B. KIETH. 1970. Ecology of red-tailedhawk predationin Alberta. Ecology,51:190-203. MAcLAREN, P. A., S. H. ANDERSON AND D. E. RUNDE. 1988. Food habits and nest characteristics of raptorsin southwesternWyoming.GreatBasin Nat., 48:548-553. NoRusIs, M. J. 1988. SPSSPC+ V2.0 Base Manual. SPSS Inc., Chicago. RAYOR, L. S. 1985. Dynamics of a plague outbreakin Gunnison's prairiedog. J. Mammal.,66:194196. SCHMUTZ, J. K. AND R. W. FYFE. 1987. Migration and mortalityof Alberta ferruginoushawks. Condor,89:169-174. AND D. J. HUNGLE. 1989. Populations of ferruginousand Swainson's hawks increase in synchronywith ground squirrels. Can. J. Zool., 67:2596-2601. SOKAL,R. R. AND J. F. ROHLF. 1981. Biometry.W.H. Freeman and Co., San Francisco. 859 p. STEENHOFF, K. AND M. N. KOCHERT. 1988. Dietary responseof threeraptorspecies to changes in J. Anim.Ecol., 57:37-48. prey densityin a natural environment. WAKELEY, J. S. 1978. Activity budgets,energyexpendituresand energyintakesofnestingferruginous hawks. Auk,95:667-676. WILKINSON, L. 1989. Systat:the systemforstatistics.Systat,Inc., Evanston,Il. 822 p. hawk during WOFFINDEN, N. D. AND J. R. MURPHY. 1977. Population dynamicsof the ferruginous a prey decline. GreatBasin Nat., 37:411-425. AND J. R. MURPHY. 1989. Decline of a ferruginoushawk population: a 20 year summary. J. Wildl.Manage., 53:1127-1132. SUBMITTED 22 JANUARY 1990 ACCEPTED 3 OCTOBER 1990