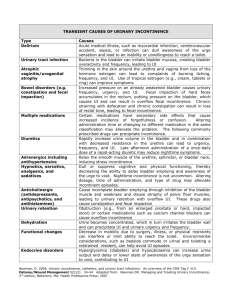

REVIEW ARTICLE

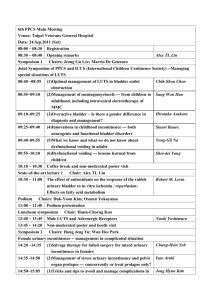

advertisement