Negatives Allston James

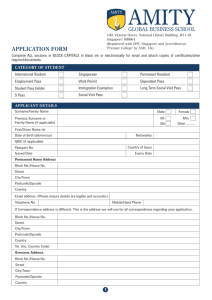

advertisement