Issue Brief No. 58 February 2013

advertisement

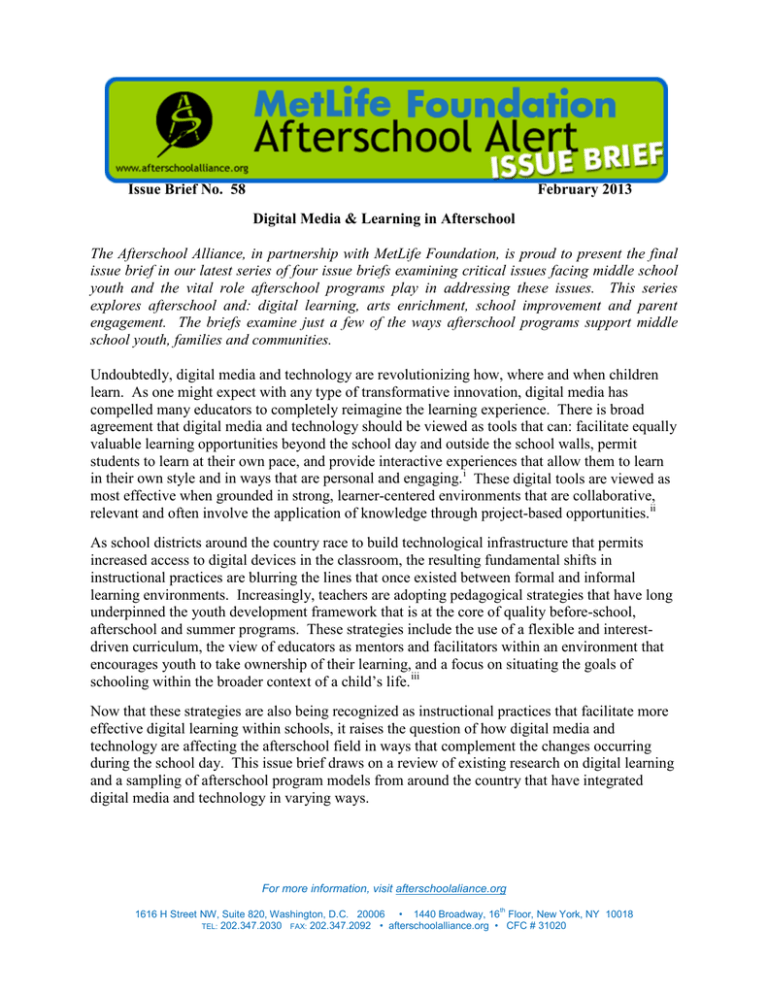

Issue Brief No. 58 February 2013 Digital Media & Learning in Afterschool The Afterschool Alliance, in partnership with MetLife Foundation, is proud to present the final issue brief in our latest series of four issue briefs examining critical issues facing middle school youth and the vital role afterschool programs play in addressing these issues. This series explores afterschool and: digital learning, arts enrichment, school improvement and parent engagement. The briefs examine just a few of the ways afterschool programs support middle school youth, families and communities. Undoubtedly, digital media and technology are revolutionizing how, where and when children learn. As one might expect with any type of transformative innovation, digital media has compelled many educators to completely reimagine the learning experience. There is broad agreement that digital media and technology should be viewed as tools that can: facilitate equally valuable learning opportunities beyond the school day and outside the school walls, permit students to learn at their own pace, and provide interactive experiences that allow them to learn in their own style and in ways that are personal and engaging. i These digital tools are viewed as most effective when grounded in strong, learner-centered environments that are collaborative, relevant and often involve the application of knowledge through project-based opportunities. ii As school districts around the country race to build technological infrastructure that permits increased access to digital devices in the classroom, the resulting fundamental shifts in instructional practices are blurring the lines that once existed between formal and informal learning environments. Increasingly, teachers are adopting pedagogical strategies that have long underpinned the youth development framework that is at the core of quality before-school, afterschool and summer programs. These strategies include the use of a flexible and interestdriven curriculum, the view of educators as mentors and facilitators within an environment that encourages youth to take ownership of their learning, and a focus on situating the goals of schooling within the broader context of a child’s life. iii Now that these strategies are also being recognized as instructional practices that facilitate more effective digital learning within schools, it raises the question of how digital media and technology are affecting the afterschool field in ways that complement the changes occurring during the school day. This issue brief draws on a review of existing research on digital learning and a sampling of afterschool program models from around the country that have integrated digital media and technology in varying ways. For more information, visit afterschoolaliance.org 1616 H Street NW, Suite 820, Washington, D.C. 20006 • 1440 Broadway, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10018 TEL: 202.347.2030 FAX: 202.347.2092 • afterschoolalliance.org • CFC # 31020 Challenges and Opportunities for the Afterschool Field “The president and I are convinced that with technology, we have an extraordinary opportunity to expand educational excellence and equity, and personalize the experience for students… Technology can enable the high-quality teaching and learning that today's students need to thrive as citizens, workers, and leaders in the digital age and the globally competitive knowledge economy.” Although many afterschool programs find ways to successfully integrate digital learning practices—or develop entirely new offerings built around digital media and learning—there are a number of challenges that inhibit the widespread adoption of these practices. Chief among them is the difficulty of securing the necessary funding to acquire and maintain a technological infrastructure. In today’s uncertain economic climate, many programs are struggling just to meet the basic needs of the children and families in their communities. With more than 3 in 5 programs (62 percent) reporting a —Arne Duncan loss of funding over the last three years, many are iv Secretary of Education cutting services in order to keep the doors open. These funding concerns, which are not unique to afterschool, strongly reinforce the need for schools and afterschool programs to work closely together as they seek to integrate digital media in teaching and learning. Afterschool providers may also have difficulty identifying the best ways to use digital tools to support their program objectives. The diverse nature of the afterschool field often limits opportunities for professional development and the sharing of promising practices across afterschool providers. Intermediaries can play a key role in supporting the sharing of instructional practices, and joint professional development organizations—like The After-School Corporation, the National AfterSchool Association, the National Network of Statewide Afterschool Networks and the National Institute on Out-of-School Time—have been offering trainings and related resources to help programs. Furthermore, in cities like Chicago and New York, groups of youth-serving institutions—including libraries, museums, community-based organizations, school- and afterschool programs, and media companies—have formed professional learning communities to connect local programs. Formally known as the Hive Learning Networks, these communities facilitate communication, knowledge-sharing and coordination across organizations serving middle- and high-school students in the respective city. The member organizations—also known as learning sites—extend learning beyond the classroom through innovative uses of digital media and technology enhanced by strong mentorship components. v Together, they are working to reinforce the notion of “anytime, anywhere learning” by creating a system that recognizes and documents how these informal learning environments use digital learning practices to support core academic standards. 2 For more information, visit afterschoolaliance.org 1616 H Street NW, Suite 820, Washington, D.C. 20006 • 1440 Broadway, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10018 TEL: 202.347.2030 FAX: 202.347.2092 • afterschoolalliance.org • CFC # 31020 The New Digital Divide Table 1. Percent of youth who have the following in their home: White Youth Black Youth Latino Youth Within disadvantaged Ages 8-18 Ages 8-18 Ages 8-18 Computer communities, afterschool 94% 89% 92% Internet Access programs have traditionally 88% 78% 74% High-Speed/Wireless been praised for helping to 61% 55% 52% Access alleviate the “digital 2 Data from: Kaiser Family Foundation. (2010). “Generation M : Media in the divide.” vi When defined in Lives of 8- to 18- Year-Olds” terms of basic access to the Internet and technology, informal learning environments certainly offer spaces where middle school youth—who might not have broadband access at home—can develop digital literacy outside of the school day. However, there is evidence to suggest that the nature of the digital divide is changing. The student-to-computer ratio between low-income and more affluent schools has closed considerably since the term was first popularized in the ‘90s. vii Additionally, the gradual decrease in the price of computers and rise in popularity of tablets and Internetenabled mobile devices has meant that more disadvantaged youth are finding ways to get online. According to a 2010 Kaiser Family Foundation Study, among youth ages 8 to 18 years of age, African-Americans exceeded whites in their use of mobile devices. viii The survey also found that a majority of all youth, regardless of race, have access to a computer and the Internet at home, although the quality of Internet access does vary (see Table 1). Today, a new digital divide is emerging—one defined in terms of interaction rather than access. There is a growing awareness of the inequalities that exist in the way that youth are interacting with digital media; whereas affluent youth are more likely to behave as “content producers,” disadvantaged youth tend to be “content consumers.” ix Through the process of creating digital content—such as blogs, zines, videos and digital art—youth who are content producers are acquiring a number of key skills and competencies, including a more comprehensive understanding of intellectual property, opportunities for cultural expression and the importance of active citizenship. x Youth who sit on the sidelines as content consumers—or, in other words, those who interact with digital media only in the context of watching videos or using social media sites—will be left behind as they enter institutions of higher education and, eventually, the workplace. The 21st century skills perceived to be essential to the future success of youth are precisely the same skills that are fostered through involvement in a participatory digital learning culture. While a divide exists between higher- and lower-income youth, overall youth interaction with digital media leans toward the content consumer side of the spectrum, with youth engaging in basic digital media activities. A 2005 Pew Internet & American Life Project survey found that half of youth ages 12 to 17 created content for the Internet. xi The Pew Internet & American Life Project’s July 2011 survey found that although 95 percent of 12 to 17 year olds use the Internet, just 27 percent record and upload videos to the Internet. xiixiii Their September 2009 survey found that only 38 percent of youth said they shared something they created—such as artwork, photos or stories—online and 21 percent said that they created their own work from pictures, songs or text that they found online. xiv A recently released report by the Digital Media and Learning Research Hub at the University of California, Irvine, further reinforces this data, stating that 3 For more information, visit afterschoolaliance.org 1616 H Street NW, Suite 820, Washington, D.C. 20006 • 1440 Broadway, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10018 TEL: 202.347.2030 FAX: 202.347.2092 • afterschoolalliance.org • CFC # 31020 “many young people take the fairly basic steps” when going online, “fewer undertake the more complex, social, or creative activities that technooptimists have hoped for them.” xv “Digital learning empowers students with the ability to customize their education to master critical knowledge and skills at the time and pace that best fits their needs. State leaders must harness the power of technology and adopt policies that will provide every student with high-quality, rigorous courses that prepare them for success in college and their careers.” Promising Practices for Digital Learning Effective digital learning practices in afterschool depend on the recognition that the use and purpose of technology in informal learning environments can vary as widely as the curricular objectives that the technology is intended to support. Across the spectrum of programs that have implemented digital learning strategies, technology is frequently used as a tool to enhance and extend broader goals that often revolve around a few key themes including creative expression, youth empowerment and civic engagement. —Jeb Bush Former Governor of Florida When used appropriately, these tools naturally support the core principles of youth development practiced by quality afterschool programs. For middle school youth in particular, these informal learning environments offer an important opportunity for them to explore their own identities and engage with the world around them in ways that are exciting, relevant and driven by their interests. A closer look at effective digital learning strategies used by some of the more successful programs reveals a few key promising practices for afterschool providers. Highly effective programming can be built around readily accessible technology. Wide Angle Youth Media in Baltimore, MD, partners with the Enoch Pratt Free Library and local schools to engage 10-15 year-old youth in an innovative program that challenges them to use digital tools as a means to explore issues impacting their communities. In the course of creating media projects, students engage in critical discussions, conduct research, interview community members and participate in reflective writing exercises. Past projects have included topics such as school bullying, gang activity, pollution and police surveillance. The most recent project involved the use of “photo walks” in the neighborhood where the program meets. The students combined the photography with sound and narration to tell a compelling story about the inequalities within a neighborhood undergoing gentrification. Digital media projects like the photo walk are accomplished using the students’ own mobile devices and basic software, illustrating that effective digital learning does not require investments in costly equipment. The program’s success is measured through pre/post student and parent surveys and staff observations of skill development using the Verified Resume tool, which is based on SCANS skills for workforce development. Students in Wide Angle Youth Media made significant gains in a number of skills, but the most notable improvements were made in technical media skills (100 percent), teamwork (95 percent), listening (80 percent) and creativity (90 percent). 4 For more information, visit afterschoolaliance.org 1616 H Street NW, Suite 820, Washington, D.C. 20006 • 1440 Broadway, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10018 TEL: 202.347.2030 FAX: 202.347.2092 • afterschoolalliance.org • CFC # 31020 Digital media and technology should support broader programmatic goals through researchbased instructional practices. “The urgency of providing a quality education means every child has access to the engaging experience that comes with powerful teaching and rigorous content available through digital learning…The teachers are here, the technology is everywhere, and the students are ready and able. Now it’s time to put it all together.” Computers4Kids (C4K) in Charlottesville, VA, uses an innovative combination of long-term mentoring, technology training, job readiness skills, academic support and college-prep guidance to target middle school students who are at risk for decreased academic achievement, lower self-esteem and increased risk-taking behavior. The students are matched with volunteer mentors who work with them to complete two in-depth, personally meaningful —Bob Wise technology projects using professional-grade President, Alliance for Excellent software in the areas of graphics, audio, Web Education design, video, animation, print, presentation and 3-D modeling. Between 2:45 and 8:00 p.m. Monday through Friday, the students are given year-round access to the program’s computers, equipment and staff to help them acquire an impressive portfolio of technology skills and projects. Graduates from the middle school program are then eligible to participate in Teen Tech (T2), a program for high school students that offers advanced technology training, college prep activities and connections to paid internships. C4K uses digital media and technology as tools to support a mission grounded in a college and career readiness framework. Students complete technology projects that meet “C4K Essentials” or project guidelines developed by staff to ensure that the students: • Demonstrate a sound understanding of technology concepts; • Use digital media to communicate and work collaboratively; • Show creative thinking; • Demonstrate critical thinking skills for planning and managing projects; and • Make informed decisions using appropriate digital tools and resources. Furthermore, C4K Essentials align with the International Society for Technology in Education’s National Education Technology Standards and include evaluation tools that effectively measure the achievements of students at different grade and ability levels. Students in C4K have exhibited positive academic achievements: 95 percent of C4K’s mentored students have graduated from high school, and 87 percent of students made improvements in at least three technology areas. Digital media and technology projects should create opportunities to empower middle school youth by providing an outlet for self-expression and a platform to assert their voices within the local and global community. 5 For more information, visit afterschoolaliance.org 1616 H Street NW, Suite 820, Washington, D.C. 20006 • 1440 Broadway, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10018 TEL: 202.347.2030 FAX: 202.347.2092 • afterschoolalliance.org • CFC # 31020 Green Energy Technologies in the City (GET City) in East Lansing, MI, is a year-round program focused on youth development in STEM and information technologies (IT). The program was founded in 2006 through a partnership between Michigan State University and the Boys & Girls Club of Lansing. GET City seeks to develop middle school youth into STEM experts who use cyber-tools to take on scientific problems of local and global relevance. Cybertoolkits include digital public service announcements, podcasts and other multi-media artifacts that contain youth-authored messages intended to educate their peers and communities about energy issues. Youth develop STEM expertise through authentic investigations of green energy challenges that are locally relevant and globally significant. They put their knowledge to work through youthled community workshops, social media outreach and creating content for the project website. In recent years, their multimedia artifacts have won statewide recognition and been featured on Detroit Public Television and Lansing’s WLNS television and in Ann Arbor’s Michigan Historic Theater. They use their materials to provide workshops for student groups, churches and community centers, and to document the community impact of energy policy for local government. In addition to GET City youth successfully securing internships with engineering labs and scholarships to university-based summer engineering programs, an external evaluation conducted by the Brown Education Alliance revealed that participation in the program significantly increased technology skills and impacted students’ aspirations and expectations. Youth are positioned as STEM experts and culturally-relevant teachers, helping them feel more empowered by their subject expertise and the knowledge that they have a voice that matters, not only within the program, but in school settings and in the community as well. Digital media and technology projects should be supported by explicit goals, while allowing for flexible implementation. YTECH Civic Voice Curriculum Programs in Seattle, WA, is based on a digital media and civics education model that enhances students’ digital literacies, communication and leadership skills while also developing their sense of belonging and investment in their communities. The middle school program, Becoming Citizens, provides youth in low-income, urban communities with the opportunity to experiment and create digital projects with tools that are often banned in schools—such as YouTube and Facebook—but are key to the students’ personal lives. The curriculum is flexible enough to be applied to activities that enhance the skills of students ranging in ages from 6 to 21, and used in programs ranging in length from 2 to 160 hours. All programs teach a core set of units with the explicit goal of developing digital literacy and creating long-term investment in civic engagement. YTECH youth review news articles, blogs and online videos created by both adults and peers, and they are led through the informationseeking and evaluation process to develop the skills needed to effectively navigate our information-saturated world. Youth are also challenged to interact in participatory online environments by synthesizing the information collected from the evaluation process with their own personal stories. A post-program online survey found that 80 percent of students agreed that the program led them to volunteer or participate in activities that helped solve problems or make the community a better place, 70 percent reported more confidence in their leadership 6 For more information, visit afterschoolaliance.org 1616 H Street NW, Suite 820, Washington, D.C. 20006 • 1440 Broadway, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10018 TEL: 202.347.2030 FAX: 202.347.2092 • afterschoolalliance.org • CFC # 31020 skills after participating in the program and 80 percent reported an increased understanding of technology after taking part in the Becoming Citizens program. Conclusion At the core of effective digital media and learning is the principle that instructional strategies should be personalized and flexible and that technology is a tool that supports effective teaching and learning practices. There is no one formula for success, but rather a multitude of ways that technology can be effectively applied to support the academic, social and emotional needs of middle school youth. Digital learning does not require educators to be experts on technology, but rather enables them to be facilitators in an environment where youth are encouraged to explore and find the answers on their own. Learner-centered strategies need staff who are invested in both the children and the program, and these strategies are most effective when educators are passionate, supportive and willing to experiment with new technology and new ways of teaching. The lower-stakes environment and higher degree of instructional freedom within afterschool settings allows these programs to more easily develop and test innovative models of technology-enabled learning. xvi These elements of effective digital learning, along with the fact that afterschool programs already excel at providing interest-driven learning opportunities, contribute to afterschool being an ideal setting for digital learning and an excellent partner to schools. i Digital Learning Now! Roadmap for Reform. Retrieved from http://digitallearningnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Roadmap-for-Reform-.pdf. ii Alliance for Excellent Education. (2012). Culture Shift: Teaching in a Learner-Centered Environment Powered by Digital Learning. Retrieved from http://www.all4ed.org/files/CultureShift.pdf. iii Herr-Stephenson, B., et. al. (2011). Digital Media and Technology in Afterschool Programs, Libraries and Museums. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Retrieved from http://mitpress.mit.edu/sites/default/files/titles/free_download/9780262515764_Digital_Media_and_Technology _in_Afterschool_Programs.pdf. iv Afterschool Alliance. (2012). Uncertain Times 2012: Afterschool Programs Still Struggling in Today’s Economy. Retrieved from http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/documents/Uncertain_Times/Uncertain-Times-2012.pdf v Hive Chicago. Retrieved from http://www.hivechicago.org/learning-networks. vi Trotter, A. (2001). “Closing the digital divide.” Education Week, 20(35), 37-40. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/202703749?accountid=11243. Kennedy, J. (2007). “African-Americans facing 'digital dimmer switch' in internet usage.” New Pittsburgh Courier. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/368244083?accountid=11243. vii Phillips, Meredith St Chin, Tiffani. (2004). “School Inequality: What Do We Know?” In K. M. Neckerman (Ed.), Social Inequality. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. 467-519. viii 2 Rideout, V.J., et. al. (2010). Generation M : Media in the Lives of 8- to 18- Year-Olds. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Menlo Park, CA. Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/8010.pdf. ix Fokkena, L. (2011). “Moving beyond access: Class, race, gender, and technological literacy in afterschool programming.” Radical Teacher, (90), 25-34,79. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/869179108?accountid=11243. x Jenkins, H, et. al. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: media education for the 21st century. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Reports on Digital Media and Learning. Retrieved 7 For more information, visit afterschoolaliance.org 1616 H Street NW, Suite 820, Washington, D.C. 20006 • 1440 Broadway, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10018 TEL: 202.347.2030 FAX: 202.347.2092 • afterschoolalliance.org • CFC # 31020 from http://digitallearning.macfound.org/atf/cf/%7B7E45C7E0-A3E0-4B89-AC9CE807E1B0AE4E%7D/JENKINS_WHITE_PAPER.PDF. xi Lenhart, A. and Madden, M. (2005). Teen Content Creators and Consumers. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2005/PIP_Teens_Content_Creation.pdf.pdf. xii Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. (2011). 2011 Teen/Parent Survey. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Shared-Content/Data-Sets/2011/July-2011-Teens-and-Online-Behavior.aspx. xiii th Purcell, K. (2012). Teens 2012: Truth, Trends and Myths. Presentation at the 27 Annual ACT Enrollment Planners Conference. Chicago, IL. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Presentations/2012/July/Teens2012-Truth-Trends-and-Myths-About-Teen-Online-Behavior.aspx. xiv Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. (2009). 2009 Parent-Teen Cell Phone Survey. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Shared-Content/Data-Sets/2009/September-2009-Teens-and-Mobile.aspx. xv Ito, M., et. al. (2012). Connected Learning: an agenda for research and design. The Digital Media and Learning Research Hub. Irvine, CA. Retrieved from http://dmlhub.net/sites/default/files/ConnectedLearning_report.pdf xvi The After-School Corporation. (2012). Where the Kids Are: Digital Learning In Class and Beyond. Retrieved from http://www.expandedschools.org/sites/default/files/digital_learning_beyond_class.pdf. 8 For more information, visit afterschoolaliance.org 1616 H Street NW, Suite 820, Washington, D.C. 20006 • 1440 Broadway, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10018 TEL: 202.347.2030 FAX: 202.347.2092 • afterschoolalliance.org • CFC # 31020