FORAGING BEHAVIOR OF BARK-FORAGING SIERRA NEVADA1

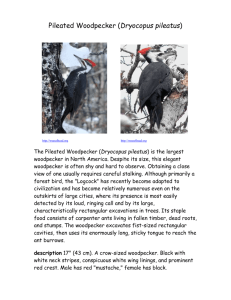

advertisement

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 201 The Condor89:201-204 0 The CooperOrnithologicalSociety1987 FORAGING BEHAVIOR OF BARK-FORAGING SIERRA NEVADA1 BIRDS IN THE MICHAELL. MORRISON Department of Forestryand ResourceManagement. Universityof California, Berkeley,CA 94720 KIMBERLY A. WITH Department of Biological Sciences,Northern Arizona University, Flagstaft;AZ 86011 IRENE C. TIMOSSI AND WILLIAM M. BLOCK Department of Forestryand ResourceManagement, Universityof California, Berkeley,CA 94720 KATHLEEN A. MILNE PacificSouthwestForest and Range Experiment Station, USDA ForestService, Fresno, CA 93710 Key words: Bark-foragingbirds;foraging behavior; Sierra Nevada. STUDY AREA The study area was the Blodgett Forest ResearchStation of the Universitv of California-Berkelev. El DoData on foragingbehavior are often usedfor examining rado County, California. This 1,200-ha forest located use of habitat and describing community structure in the mixed-conifer zone (see Griffin and Critchfield among co-occurring species of birds using the same 1972) at about 1350 m elevation in the central-western resourcebase(e.g.,Johnson1966, Eckhardt 1979, Rus- Sierra Nevada. The forest consistedof five predominant conifer species:incensecedar (Calocedrusdecurterholz 1981). Differencesin tree species,foliage morrens; 25% of total basal area, unpubl. data); white fir phology, and bark structuremay influence the types of prey taken and the speciesof bird using the substrate (Abiesconcolor,21%); ponderosapine (Pinus ponderosa, 19%); sugar pine (P. lambertiana, 10%); and (e.g.,Jackson1979, Holmes and Robinson 1981, Robmenziesii, 15%);and one deinson and Holmes 1984). Elucidation of foranine.beDouglas-fir (Pseudotsuga haviors and tree speciespreferencesis import&t Tf we ciduousspecies,California black oak (Quercuskellogare to determine the role of birds in forest ecosystems, gii, 8%). The forest has been divided into 5- to 37-ha and make informed decisionsregardingmanagement compartments to be managed under various silviculof these forests. In this study we describe the use of tural systemsand is now mostly mature (>70 years tree species,foraging modes, and foraging substrates old) conifer that is at or near rotation (cutting) age. by a group (or “guild,” sensuRoot 1967) of bark-forDuring 1983 and 1984 we selected24 compartments agingbirds breeding in the western Sierra Nevada. A (of mature conifer); compartments totalled about 420 similar study on foliage insectivores was conducted ha (range = 7-37 ha). Durine. 1985 we selected nine previously near our study area (see Airola and Barrett compa<ments, seven’ofwhichdiffered from thoseused during 1983 and 1984;the 1985 compartmentstotalled 1985). The speciesanalyzed, in order of decreasingabun- 210 ha (range = 15-37 ha). Selection was not comdance, were: Red-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta canaden- pletely randomized becauseforest silvicultural plans sis),Brown Creeper(Certhia americana), Red-breasted often determined which compartmentswere available Sapsucker(Sphyrapicusruber), White-headed Woodfor use.In most casescompartmentswere not adjacent pecker (Picoidesalbolarvatus),Hairy Woodpecker (P. to each other. villosus),and Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopuspileatus) (seeMorrison et al. 1986). All are typical inhab- METHODS About 1250 person-hr were spent observing foraging itants of coniferousforestsin the Sierra Nevada (Grinnell and Miller 1944). The Downy Woodpecker behavior during the summers (May to mid-July) of (Picoidespubescens)and Northern Flicker (Colaptes 1983 to 1985. We tried to collect data for all species auratus) occurredrarely in our study area and are not at an equal rate throughouteach summer to lessenthe influence of possible temporal variation in behavior analyzed herein. among species. Observers systematically walked through a compartment recordingdata on birds as en’ Received 23 June 1986. Final acceptance29 Sep- countered. Only one individual of a specieswas obtember 1986. served at a particular place and time to avoid the po- is 202 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS FIGURE 1. Use (%) of tree species(upper bar), foragingmodes(middle bar), and foragingsubstrates(lower bar) for birds at BlodgettForest during the summers of 1983 to 1985. We defined the following foraging motions: gleanprey taken from the surfaceof the substratewhile the bird was perched; hover-glean-prey taken from the surfaceof the substratewhile the bird was flying; sallying (hawk, flycatch)-bird leaves a perch, attempts to catch flying prey on the wing, and returns to a perch (see also Eckhardt 1979); probe-prey taken from an opening, such as bark crevices;and peck-bill forcefully struckat the surface.Other foragingmotions (e.g., flush-pursuit, aerial flight, chase)were used little and are reported here as a combined “other” category. Flaking of bark was noted primarily during winter at BlodgettForest (seeMorrison et al. 1985) and was not included as a separatecategoryherein. Data for males and females were combined for this analysis. Although intersexual differencesin foraging behavior are known for many woodpeckers(e.g., JSilham 1965, Grubb 1975, Williams 1980) we combined sexesbecause:(1) we only had marginally enoughdata for intersexualcomparisonsin two of the woodpecker species;and (2) we could not usually differentiate sex in the nonwoodpeckerspecies.Except for the Pileated Woodpecker, our sample sizesgreatly exceededthose necessaryfor analysisof avian foragingbehavior (i.e., observationson > 35 individuals; Morrison 1984). The distribution of foragingactivities for useof tree species, modes, and substrateswere examined separately for each bird speciesby chi-squareanalysis.All data were analyzed using SPSSX (SPSS 1983). RESULTS tential problem of correlatedactivities of co-occurring individuals of the same species. Once encountered,the foraging activity of an individual was recorded for a minimum of 10 set to a maximum of 30 sec. The observer either timed the activity period with a stopwatchor by counting; only birds actively foraging are analyzed herein. The following data were recordedfor eachindividual: species; sex; type of foraging motion (defined below); species of plant; substrateto which the foraging motion was directed; foraging substrate;perch height; and plant height. Heights and distanceswere visually estimated. The dominant foragingactivity (e.g.,motion, substrate, height) observedduring the timed period for each individual was recorded. In the results that follow, the distribution of foraging activities for each bird speciesfor use of tree species, and foraging modes and substrates,were significantly different (chi-squareanalysis,P c 0.05) except as noted. Differences were evident in the percent use of different tree speciesby birds; all distributions were significantly different exceptfor the Pileated Woodpecker, which used all tree species with roughly equal frequency. All speciesexcept the White-headed Woodpeckerand (to a lesserextent) the Brown Creeper demonstrated high use of white fir, and all speciesexcept the Red-breasted Sapsuckershowed high use of ponderosapine (Fig. 1). Relative to the other species,the Pileated Woodpecker occurred more on oak, and the TABLE 1. Foragingheight and dbh of foragingtreesfor birds at Blodgett during the summersof 1983 to 1985.” Values with same letter (A, B, C, or D) are not significantly different (P z 0.05) as determined by Duncan’s new multiple range test. Species Red-breasted Sapsucker Hairy Woodpecker White-headed Woodpecker Pileated Woodpecker Red-breasted Nuthatch Brown Creeper aSamplesizes= numberof individuals observed. ??a 91 89 116 48 126 123 Foragingheight (m) R 11.5 10.6 11.6 17.4 13.9 6.7 SD 6.63C 6.68C 6.59C 8.99A 6.49B 4.46D Foragingtree dbh (cm) + SD 41.8 44.5 58.9 90.0 47.7 47.9 23.55C 24.3OC 27.56B 42.72A 22.63C 25.64C SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 203 TABLE 2. Vigor of foragingtrees and foraging substratesused by birds at Blodgett Forest during the summers of 1983 to 1985. Sample sizes in Table 1. Foraging tree (%) Species Red-breasted Sapsucker Hairy Woodpecker White-headed Woodpecker Pileated Woodpecker Red-breastedNuthatch Brown Creeper Foraging substrate (%) Alive Dead Alive Dead 16.4 46.6 81.1 55.3 82.8 86.2 23.6 53.4 18.9 44.1 11.2 13.8 72.0 32.0 61.0 21.5 65.0 18.3 28.0 68.0 39.0 72.5 35.0 21.7 White-headed Woodpecker and creeper were unique in exhibiting a greater-useof incensecedar. In addition, the White-headed Woodvecker had a higher use of sugarpine than the other-species. Only the sapsuckerand nuthatch were observedflycatching. The creeper foraged primarily by gleaning and probing. The nuthatch gleaned extensively, but spentroughly equal time probing and pecking.In contrast to the other woodpeckers, the sapsuckerspent similar amounts of time pecking and gleaning. The other woodpeckerspecked and probed >70% of the time (Fig. 1). All speciesexceptthe nuthatchconcentratedforaging activities on trunks (Fig. 1). The nuthatch used a wide variety of substrates,including twigs and small-sized branches.Although concentratingactivities on trunks, the Pileated Woodpecker also showed substantialuse of medium-sized branches(Fig. 1). Pileated Woodpeckers foraged significantly higher than all other species,the nuthatchforagedhigher than all remaining species,and the creeper foraged significantly lower than all other species(Table 1). The remaining three species, the White-headed and Hairy woodpeckers,and Red-breasted Sapsucker,had mean foragingheights of about 10 to 11 m. The Pileated Woodpecker used significantly larger (by diameter at breast height; dbh) trees than all other species;the White-headedWoodpeckerusedlargertrees than the remaining species(Table 1). The averagedbh of foraging trees used by the other specieswas similar (about 42 to 48 cm dbh). The sapsucker, White-headed Woodpecker, nuthatch, and creeper spent the majority of their time foragingon the live parts of trees (Table 2). The Hairy and Pileated woodpeckers foraged in live and dead trees with similar frequency, but about 70% of their foragingtime was on dead substrates(Table 2). DISCUSSION Our results indicated that the birds we studied used different combinations of the foraging behaviors examined. All speciesexcept the sapsuckershowedhigh use of ponderosa pine; high use of white fir was observed for all except the creeper and White-headed Woodpecker;the white-headed and creeperhad higher use of incense cedar, and the white-headed also used more sugarpine than the other species.Where overlap occurredin tree speciesuse (ponderosapine and white fir), the bird speciesuseddifferent foragingmodesand/ or other tree speciesto a greater extent (e.g., compare the Hairy and White-headed woodpeckers). Differences in foraging height, type of substrateused, and tree and substratevigor also differed among species. For example,althoughthe creeperand nuthatchgleaned extensively (in contrast to most woodpeckers), they foraged at different averageheights, and the nuthatch used a wider range of foraging substrates.The sapsuckerdiffered from the other woodpecker speciesin severalways,most notably in its higher useof gleaning. The use of living substratesby the sapsucker,in contrast to the predominate use of dead wood by other woodpeckers,is likely a reflection of the use of sap as a food sourceby the sapsucker(see Vemer and Boss 1980). A changein the speciesor size composition of the forest would likely alter the pattern of resourceuse by the birds we observed. Such changesare, in fact, underway in the Sierra Nevada due to silvicultural activities (see Morrison et al. 1985). For example, external bark structurechangeswith tree diameter (e.g., usually becomingthicker and more deeply furrowed with age), which affectsprey abundanceand the ability of birds to obtain the prey (Jackson1979, also Morrison et al. 1985). The current trend in the western Sierra Nevada is conversionfrom mixed-conifer to monotypic stands of ponderosapine, or mixed standsof ponderosapine and lesseramounts of Douglas-fir and fir (R. C. Heald, Manager, Blodgett Forest, pers. comm.). Precommercial- and commercial-thinning activities also remove much of the understory of small, commercially undesirable species or less-vigorous individuals. Althoughmost speciesin our study usedponderosapine, they also showedhigh useof white fir. Further, several speciesexhibited high use of incense cedar. Although we would predict that conversion to ponderosa pine would probably not eliminate any specieswe studied, sucha changewould likely alter the abundanceof the birds. The ramifications of such changeson interactions within the bird community, and within the forest ecosystemitself (e.g., bird-insect interactions),are unknown. Our results, as well as those of Airola and Barrett (1985) for foliage insectivores, indicate that efforts should be made to maintain a high diversity of tree species and size classesthroughout the mixedconifer zone of the Sierra Nevada. This paperelucidatesforagingbehaviorsusedby bark foragersduring springand summer. In a related study, Morrison et al. (1986) found a significant increase in the use of incensecedar by many birds during winter. This changewas related to prey availability and was 204 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS accompaniedby changesin foragingmode. Therefore, biologistsand resourcemanagersshouldview the present paper in light of suchseasonalchangesin behavior. Unfortunately, we did not measure prey availability during the breedingperiod, a shortcomingthat should be eliminated in future studies.Detailed analysisof the surfacearea of bark available to birds, including limbs and twigs, should also be quantified in the future. We appreciate field assistanceduring parts of this study provided by P. N. Manley, S. A. Laymon, R. E. Etemad, and J. M. Anderson. R. C. Heald and staff at Blodgett Forest are thanked for logistical support. J. Vemer, C. J. Ralph, R. T. Holmes, and an anonymous referee gave very useful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. Comments made on another but related manuscriptgiven by R. L. Hutto, F. C. James, and T. W. Schoenerplayed a substantialrole in evaluation of the resultsreported herein. LITERATURE CITED AIROLA,D. A., AND R. H. BARRETT. 1985. Foraging and habitat relationshipsof insect-gleaningbirds in a Sierra Nevada mixed-conifer forest. Condor 87:205-216. ECKHARDT,R. C. 1979. The adaptive syndromesof two guilds of insectivorousbirds in the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Ecol. Monogr. 49:129-149. GRIFFIN,J. R., AND W. B. CRITCHL~ELD.1972. The distribution of forest trees in California. USDA For. Serv. Res. Pap. PSW-82. GRINNELL,J., AND A. H. MILLER. 1944. The distribution of the birds of California. Pacific Coast Avifauna No. 27. GRUBB,T. C., JR. 1975. Weather-dependentforaging behavior of some birds wintering in a deciduous woodland. Condor 77: 175-l 82. HOLMES,R. T., AND S. K. ROBINSON. 1981. Tree speciespreferencesof foraginginsectivorousbirds in a northern hardwood forest. Oecologia 48:3 l35. JACKSON, J. A. 1979. Tree surfacesas foraging substratesfor insectivorousbirds, p. 69-93: Zi J. G. Dickson. R. N. Conner. R. R. Fleet. J. C. Kroll. and J. A: Jackson[eds.]:The role of insectivorous birds in forest ecosystems.Academic Press,New York. JOHNSON, N. K. 1966. Bill size and the question of competition in allopatric and sympatric populations of Dusky and Gray flycatchers.Syst. Zool. 15:70-87. K~LHAM,L. 1965. Differences in feeding behavior of male and female Hairy Woodpeckers.Wilson Bull. 77:134-145. MORRISON,M. L. 1984. Influence of sample size and sampling designon analysisof avian foragingbehavior. Condor 86: 146-150. MORRISON,M. L., I. C. TIMOSSI,K. A. WITH, AND P. N. MANLEY. 1985. Use of tree speciesby forest birds during winter and summer. J. Wildl. Manage. 49:1098-l 102. MORRISON.M. L.. K. A. WITH. AND I. C. TIMOSSI. 1986. ’ The structure of a forest bird community during winter and summer. Wilson Bull. 98:214230. ROBINSON, S. K., AND R. T. HOLMES. 1984. Effects of plant speciesand foliage structure on the foraaina behavior of forest birds. Auk 101:672-684. RooT~R~B. 1967. The niche exploitation pattern of the Blue-grayGnatcatcher.Ecol. Monogr. 37:3 17350. RUSTERHOLZ, K. A. 1981. Competition and the structure of an avian foragingguild. Am. Nat. 118:173190. SPSS,INC. 1983. SPSSX user’s guide. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York. VERNER,J., ANDA. S. Boss. 1980. California wildlife and their habitats:western Sierra Nevada. USDA For. Serv. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-37. WILLIAMS,J. B. 1980. Intersexual niche partitioning in Downy Woodpeckers.Wilson Bull. 92:439-45 1.