What has been driving living standards? Richard Blundell October 14

What has been driving living standards?

HM Treasury Labour Market Conference

October 14 th 2013

Richard Blundell

University College London and Institute for Fiscal Studies

Thanks to Jonathan Cribb, Wenchao Jin, Robert Joyce and Cormac O’Dea.

This research is funded by the ERSC Centre (CPP) at IFS.

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

Outline

I will look (briefly) at Incomes, Earnings and Consumption

All three measures have something important to say.

1.

Incomes: Working-age and Pensioners

2.

Earnings: Wage Changes, Employment and Productivity

3.

Consumption: Durable and Non-durable Expenditures

4.

Prospects

Under each heading some summary points and supporting evidence.

Draw on three references to recent IFS research:

Ø Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK.

– IFS Report R81 , http://www.ifs.org.uk/comms/r81.pdf

Ø What Can Wages Tell Us about the Productivity Puzzle?

– IFS Working Paper, W13/11; forthcoming Economic Journal , http://www.ifs.org.uk/wps/ wp201311.pdf

Ø Household Consumption through Recent Recessions.

– Fiscal Studies , 34(2), June 2013, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1475-5890.2013.12003.x/abstract

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

1. Incomes

• Leading up the recession:

• income growth had slowed in early 2000s.

• pensioners/ working-age childless were doing relatively well/ badly

• During recession and immediately afterwards:

• real earnings for those in work fell; benefits/tax credit incomes were robust.

• employment rates fell for young adults but not for older ones.

• As a result: a) income inequality fell (despite rise in earnings inequality among workers) b) young adults did worst; pensioners did best (again)

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

1996-‐97 to 2011-‐12: pensioners did rela&vely well; working-‐age childless rela&vely badly

4.0%

3.5%

3.0%

2.5%

2.0%

1.5%

1.0%

0.5%

0.0%

-‐0.5%

-‐1.0%

10 20

Parents and children

Working-age without children

Pensioners

30 40 50

Percentile point

60 70 80 90

Notes and source: see Figure 5.2 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK: 2013

...and on an aFer-‐housing-‐cost (AHC) basis

4.0%

3.5%

3.0%

2.5%

2.0%

1.5%

1.0%

0.5%

0.0%

-‐0.5%

-‐1.0%

10 20

Parents and children

Working-age without children

Pensioners

30 40 50

Percentile point

60 70 80 90

Notes and source: see Figure 5.2 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK: 2013

Trends not uniform: slower growth from early 2000s

125

Mean income Median Income

120

115

110

105

100

Source: Family Resources Survey, various years

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Trends not uniform: slower growth from early 2000s

125

Mean income Median Income

120

115

110

105

100

Source: Family Resources Survey, various years

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

... and large falls aFer the recession

125

Mean income Median Income

120

115

110

105

100

Source: Family Resources Survey, various years

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Income sources, 2007–08 to 2009–10: steady income growth due to benefits/tax credits

Earnings

Benefits and tax credits

Savings and private pension income

Self-‐employment income

Other

Taxes and other deduc&ons

Total income

-‐0.7

-‐0.1

0.4

0.3

0.2

2.2

2.4

-‐2 -‐1.5 -‐1 -‐0.5 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3

Contribu&on to income growth between 2007–08 to 2009–10

(in percentage points)

Source: Table 2.4 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2013

Notes: This is a very slightly different sample to the overall income sta&s&cs. Households with nega&ve incomes are dropped. This makes a small difference to falls in income

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Income sources, 2009–10 to 2011–12: large income falls due to falling earnings

Earnings

Benefits and tax credits

Savings and private pension income

Self-‐employment income

Other

Taxes and other deduc&ons

Total income

-‐5.7

-‐1.0

-‐2.0

-‐0.7

-‐0.4

-‐7.5

-‐10 -‐8 -‐6 -‐4 -‐2

Contribu&on to income growth between 2009–10 to 2011–12

(in percentage points)

0

Source: Table 2.4 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2013

Notes: This is a very slightly different sample to the overall income sta&s&cs. Households with nega&ve incomes are dropped. This makes a small difference to falls in income

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

2

2.4

4

Income sources: 2007–08 to 2011–12

Earnings

Benefits and tax credits

Savings and private pension income

Self-‐employment income

Other

Taxes and other deduc&ons

Total income

-‐5.9

-‐1.5

-‐1.6

-‐0.1

-‐5.3

-‐10 -‐8 -‐6 -‐4 -‐2

Contribu&on to income growth between 2007–08 to 2011–12

(in percentage points)

0

Source: Table 2.4 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2013

Notes: This is a very slightly different sample to the overall income sta&s&cs. Households with nega&ve incomes are dropped. This makes a small difference to falls in income

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

1.2

2.7

2 4

Weekly earnings inequality (among workers) rose between 2007-‐08 to 2011-‐12...

0.0%

-‐1.0%

-‐2.0%

-‐3.0%

-‐4.0%

-‐5.0%

-‐6.0%

-‐7.0%

-‐8.0%

-‐9.0%

-‐10.0%

-‐11.0%

-‐12.0%

10 20 30 40 50 60

Percentile point

Note: towards bottom, much driven by falls in hours worked

(not falls in hourly wages)

70 80 90

Notes and source: see Figure 3.10 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK: 2013

...but net result was s&ll a fall in income inequality

8%

4%

0%

-4%

-8%

2007–08 to 2009–10 2009–10 to 2011–12 2007–08 to 2011–12

-12%

10 20 30 40 50 60

Percentile point

Source: Figure 3.5 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2013

70 80 90

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Median income changes by age (BHC, GB)

2007–08 to 2011–12 2001–02 to 2007–08

4%

3%

2%

1%

0%

-1%

-2%

-3%

-4%

0s 10s 20s 30s

Age

40s 50s

Notes and source: see Figure 5.7 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK: 2013

60s 70s

2. Earnings: Wages and Employment

• Average real hourly wages fallen since this recession began.

– Why and will the trend continue?

• ‘Effective labour supply’ is higher now than during previous recessions, due (perhaps) to welfare policy changes and wealth shocks,

– increasing in the long-run (due to social and policy changes) and in the short-run (due to wealth shocks and long term real wage declines).

• Workforce composition has shifted towards more productive types,

– as in previous recessions, yet real wages have fallen.

• These real wage falls have occurred within individuals:

– unprecedentedly high proportions of employees experienced nominal wage freezes,

– especially in the lower-middle of the wage distribution and in the absence of collective agreements.

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

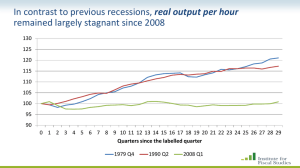

In contrast to previous recessions, real output per hour has at best been stagnant since 2008: why?

Real output per hour

120

115

110

105

100

95

90

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Quarter since the labelled one

1979Q4 1990Q2 2008Q1 Linear trend (90Q2-‐08Q1)

Average real hourly wages have also been stagnant

120

Average real male hourly wage (using GDP deflator)

115

110

105

100

95

0 1 2 3 4 5

Years since the year in which the recession began

1979 1990 2008 Linear trend 1990-‐2008

6

The UK is different.....

1.15

1.1

1.05

1

0.95

0.9

0.85

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

UK, GDP per hour

US, GDP per hour

France, GDP per hour

Germany, GDP per hour

UK, average wage

US, average wage

France, average wage

Germany, average wage

Employment and labour market par&cipa&on

• Labour market par&cipa&on has held up beier during this recession than previous ones. For example:

– Employment rates fell less (and unemployment rates increased less)

Employment and labour market par&cipa&on -‐ employment rate of 23-‐64-‐year-‐olds by recession

2.0%

0.0%

-2.0%

-4.0%

-6.0%

0 1 2 3 4 5

-8.0%

-10.0%

Year since the start of recession

Source: LFS every year. No data point for year 1980, 1982. Quarter 2 is used for years since 1992. male, from 1979 female, from 1979 male, from 1990 female, from 1990 male from 2008 female, from 2008

Change to the propor&on of 23-‐64-‐year-‐olds who are unemployed by recession

6.0%

5.0%

4.0%

3.0%

2.0%

1.0%

0.0%

0 1 2 3 4 5

Source: LFS every year. No data point for year 1980, 1982. Quarter 2 is used for years since 1992. male, from 1979 female, from 1979 male, from 1990 female, from 1990 male from 2008 female, from 2008

Employment and labour market par&cipa&on

• Some increase of par&cipa&on can be aiributed policy changes, e.g. :

– Labour supply has increased among lone parents as a result of job search condi&ons aiached to benefit claims

– Older workers are re&ring later as a result of increased SPA for women

Change to lone mothers’ par&cipa&on rate since policy change

4%

2%

0%

-‐2%

-‐4%

-‐6%

-‐8%

14%

12%

10%

8%

6%

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

Quarter since the last quarter before policy change youngest kid 12-‐15, 2008Q3 youngest kid10-‐11, 2009Q3 youngest kid 7-‐9, 2010Q3 youngest kid 5-‐6, 2011Q3

Impact of SPA increase for women on employment

60%

55%

50%

45%

40%

35%

30%

Counterfactual male 60-‐64 employment rate

LFS employment rate 60-‐64 men

Counterfactual female 60-‐64 employment rate

LFS employment rate 60-‐64 year old women

Note: counterfactual employment rates are estimated. See Cribb et al (2013) “Incentives, shocks or signals: labour supply effects of increasing the female state pension age in the UK”

Employment and self-‐employment rate of older people

-‐4%

-‐6%

-‐8%

-‐10%

4%

2%

0%

-‐2% employment rate 60-‐74 male employment rate 60-‐74 female self-‐employment rate 60-‐74 male self-‐employment rate 60-‐74 female

Employment status of 16-‐22-‐year-‐olds

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

% in work % unemployed

Source: LFS 2 nd

quarter every year

Employment and labour market par&cipa&on

• There is also some (weak) evidence that par&cipa&on amongst older people has increased as a result of shocks to housing or financial wealth

§ But probably a response to falling expected real wages too.

Can changes in the composi&on of the workforce explain the fall in real hourly wages?

• Short answer: no

– unlike, to an extent, in other countries.

• As in previous recessions, the composi&on of the workforce shiFed towards more produc&ve workers,

– hence we would have expected the average real wage to increase

(other things being equal).

• What has been different in this recession is that the returns to those characteris&cs have fallen substan&ally.

• This is true even amongst workers who keep their jobs, who have experienced nominal wage freezes/real wage falls,

– May have been facilitated by the reduced power of labour market ins&tu&ons (e.g. unions) since previous recessions.

Average real hourly wage by age group (RPI deflated)

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

16-‐17

18-‐25

26-‐35

36-‐45

46-‐55

56-‐64

65+

Average real hourly wage by qualifica&on among young people

14.00

12.00

10.00

8.00

6.00

4.00

2.00

0.00

18-‐21, GCSEs or above

18-‐21, no GCSEs or equilvants

22-‐24, degree or above

22-‐24, GCSEs, no degrees

22-‐24, no GCSEs

NEET rate among young people

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

18-‐21, GCSEs or above

18-‐21, no GCSEs or equilvants

22-‐24, degree or above

22-‐24, GCSEs, no degrees

22-‐24, no GCSEs

%change to real hourly wage since last year, by period

% facing nominal wage freeze in the coming year by current wage quintile

16%

14%

12%

10%

8%

6%

4%

2%

0%

Lowest-‐paid 20% 2nd quin&le 3rd quin&le 4th quin&le

Source: New Earnings Survey Panel Dataset 1975-‐2011. There are 20,000-‐30,000 observa&ons underlying each data point.

Highest-‐paid 20%

More nominal pay freezes in the absence of collec&ve agreement since 2008

3. Consumption

• Expenditure falls have been deeper than in previous recessions.

– Note that the start of the fall is coincident with the fall in GDP (not income).

• Unusually expenditure on consumer nondurables has fallen most

– Especially among the young and to some extent among the middle aged. Less for the old.

– Temporary VAT reduc&on?

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Non-‐ and semi-‐durables

110

108

106

104

102

100

98

96

94

92

90

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Quarters since beginning of recession

1980

1990

2008

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Durables

125

120

115

110

105

100

95

90

85

80

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Quarters since beginning of recession

1980

1990

2008

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Components of GDP

15

10

5

0

-‐5

-‐10

-‐15

-‐20

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Net exports

Govt. purchases

Consumer durables

Nondurable consump&on

Corporate investment

Propor&onate Fall in Each Component

110

105

100

95

90

85

80

75

70

65

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Govt. purchases

Consumer durables

Nondurable consump&on

Corporate investment

Consumption

• Homeowners have made the largest cuts.

– In past recessions there was liile difference between owners and renters.

• Saving ra&os are lower than during the early 1980s and early 1990s

– but haven risen drama&cally since 2008 (and pension contribu&ons higher).

• The data points to an expecta&on of a permanent fall in living standards,

– especially among the young and middle-‐aged.

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

4. Summary and … Prospects …

• What has driven living standards?

• Changes in the labour market are a key factor behind the changes,

– especially for younger families/singles rela&ve to pensioners.

• Real wages and employment tell much of the story. Benefit changes have also been important drivers.

– the poor employment and earnings performance of young adults maps into big falls in their incomes rela&ve to older workers.

• The con&nued catch-‐up of pensioners rela&ve to working-‐age adults is in large part due to the sharp falls in real earnings and rela&vely robust benefit rates.

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Simula&ons up to 2015–16

2%

0%

-2%

-4%

-6%

2007–08 to 2011–12 2011–12 to 2015–16 2007–08 to 2015–16

-8%

10 20 30 40 50

Percentile point

60 70 80 90

Note: Figure taken from Brewer et. al. (2013), Fiscal Studies, Vol. 34, No. 2, June 2013, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 179–201.

Published before the latest HBAI release. The 2011–12 income distribu&on is therefore a simula&on, but is extremely similar to the actual data.

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Employment shares of occupation groups

Note: the discontinuities in occupation classification in 2001 and 2011 have been addressed in the following way. For the conversion of SOC 1990 to SOC 2000, we look at individuals who were surveyed in 2000Q4 and 2001Q2 and stayed with the same employer and infer the transition matrix from this group. For the conversion of

SOC2010 to SOC 2000, we used the ONS two-way tabulation of the LFS 2007 Q1 sample by the major occupation groups under the two SOC systems.

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

(RPI deflated) Real wages by occupation group since 1993

Note: the low-skilled wage would end up around the 1993 level if we use CPI instead of RPI. Each log wage series is normalized to 0 in 1993.

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Prospects - I

• Younger workers and families are ac&ng as if they expect a long-‐run fall in rela&ve living standards

– evidence from consump&on and saving.

• Real wages, produc&vity and capital investment have slow to pick up

– we can expect the paiern of lower real wages to con&nue, but with fairly buoyant employment due to increased supply.

• Most falls in real earnings have happened (but low/no real growth)

– fiscal contrac&on implies >£20 bn year of benefit cuts by end of this parliament

– trends by age maybe more durable, e.g. pensioner benefits protected

• The number of rou&ne jobs near the middle of the earnings distribu&on has declined steadily &ll 2009

– more jobs are now professional or managerial. In the late 90s to early 2000s, wages grew fast for high (and mid-‐skilled) occupa&ons, but this slowed down around 2003 and real wages fell since 2009.

• Suggests longer term earnings growth will mostly come from high-‐ skilled occupa&ons, with some at the very boiom.

Prospects - II

• But s&ll much to do in focussing on older workers in general, on return to work for parents/mothers, and on entry into work.

• There are s&ll some poten&al big gains here,

– for example, as (higher skilled) women age in the workforce.

• Tax/welfare reforms to enhance earnings (from Mirrlees ):

– refocus incen&ves towards transi&on to work, return to work for lower skilled mothers and on enhancing incen&ves among older workers.

• Produc&vity is s&ll the key,

– (financial) capital misalloca&on and poten&al investment returns.

• Human capital and ‘on the job’ wage/produc&vity complementarity

– note the rela&ve importance of mismatch of entry skills in the recession.

• Produc&vity and wages are closely related but note recent growth in the wedge between labour costs and hourly wages,

– the growing importance of pensions and NI in the UK,

– what will the trends in this wedge look like?

Employer contribu&ons to pension funds – in constant prices terms

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes: Data for Q4 2012 is not yet published so has been estimated based on Q4 2011 to Q3 2012 data

Prospects - II

• But s&ll much to do in focussing on older workers in general, on return to work for parents/mothers, and on entry into work.

• There are s&ll some poten&al big gains here,

– for example, as (higher skilled) women age in the workforce.

• Tax/welfare reforms to enhance earnings (from Mirrlees ):

– refocus incen&ves towards transi&on to work, return to work for lower skilled mothers and on enhancing incen&ves among older workers.

• Produc&vity is s&ll the key,

– (financial) capital misalloca&on and poten&al investment returns.

• Human capital and ‘on the job’ wage/produc&vity complementarity

– note the rela&ve importance of mismatch of entry skills in the recession.

• Produc&vity and wages are closely related but note recent growth in the wedge between labour costs and hourly wages,

– the growing importance of pensions and NI in the UK,

– what will the trends in this wedge look like?

Employment rate by highest qualifica&ons achieved, 16-‐59 year olds

95%

90%

85%

80%

75%

70%

65%

60%

55%

50%

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 degree or above level 2 and 3 level 1 or below

Note: level 2 is GCSE grade C or above.

© Ins&tute for Fiscal Studies

Par&cipa&on rates over &me

100.0%

90.0%

80.0%

70.0%

60.0%

50.0%

40.0%

30.0%

20.0%

10.0%

0.0%

23-64, male

23-64, female

65-84, male

65-84, female