NORTHVIEW ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: AN ITERATIVE PARTICIPATORY PROCESS IN SCHOOLYARD PLANNING... by

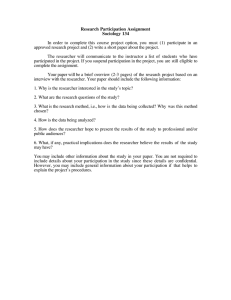

advertisement