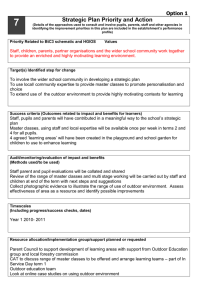

Outdoor Learning Practical guidance, ideas and support for www.educationscotland.gov.uk

advertisement