KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY FACULTY PERSPECTIVE, OPINIONS, AND

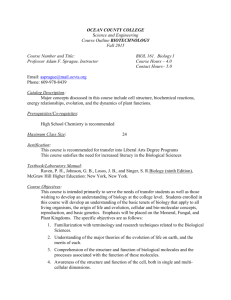

advertisement