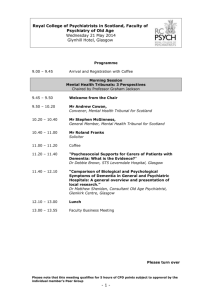

G l a s g o w C... M a y 2 0 0 2

advertisement