languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum

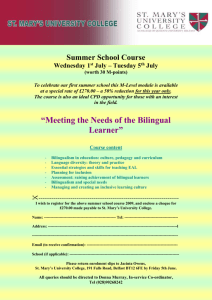

advertisement

languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum First published 2006 © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2006 ii languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Contents page Notes on revision 1 Introduction 3 Bilingualism – an asset for all 4 1 Cheer home the front-runner!_________________________________ 4 2 Lead into reading_ ________________________________________ 5 3 Home confidence into school confidence_______________________ 6 4 Bridges to partnership_ _____________________________________ 7 5 The benefits of bilingualism_ _________________________________ 7 6 Bilingualism is catching!_ ____________________________________ 9 Recognising a child’s language assets 10 1 Enrolment________________________________________________11 2 Observation and profiling____________________________________11 3 Involvement of parents/carers_______________________________ 12 4 Reporting: promoting partnership with the home_________________ 13 Realising a child’s language assets 16 1 Environment and ethos____________________________________ 16 2 Supporting learning_ ______________________________________ 17 3 Opportunities for home language development within the 3–18 curriculum__________________________________ 18 iii languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Contents (continued) Building upon the home language – development of English as a second, or additional, language (EAL) 22 The process of second language development 23 1 Plenty of listening time is important____________________________ 23 2 Visual support for meaning__________________________________ 24 3 Other children can be the best teachers_______________________ 24 4 English is best acquired through mainstream learning activities_ _____ 26 5 Errors are often a sign of language growth_ ____________________ 28 Conclusion 29 Checklists for action 30 Policy_ ___________________________________________________ 30 Ethos_____________________________________________________ 30 Professional development_____________________________________ 30 Partnership with the home and community________________________ 31 Classroom practice – home language development________________ 31 Classroom practice – second, or additional, language development____ 32 References iv page 33 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Notes on revision This document is a revision of Languages for Life: Bilingual Pupils – 5–14, published by the Scottish Consultative Council on the Curriculum in 1994. At that time it was well received, and has been much used since, as a source of guidance for those supporting developing bilingual learners within the 5–14 curriculum. It has been influential in the development of good practice in Scotland because of its emphasis on the importance of the home language for bilingual children’s academic achievement and social and personal development. It also stresses the need to plan support beyond the child’s acquisition of social fluency, to ensure that the child has meaningful access to the whole curriculum. Since the publication of the original document, there have been important developments in Scottish education. This revised document takes these into account. Firstly, its focus moves beyond that of the 5–14 curriculum, to consider raising the achievement of bilingual children within the 3–18 curriculum, in line with A Curriculum for Excellence (Scottish Executive, 2004). It also recognises that bilingual learners, apart from their continuing need for support in the development of English, have considerable strengths and also may have other additional support needs which require to be addressed within an inclusive educational setting. Thus, the present document relates to the provisions of the Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004. Since 1994, there has been considerable research worldwide into the development of English as a second, or additional, language. This research1 has established the importance of sustained development in the child’s home language(s), if the child is to catch up, in general academic development and English language proficiency, with the English-speaking peer group and still maintain full cultural and linguistic links with the home community. Research into the literacy development of bilingual children has shown that reasons for literacy failure are likely to be very different from those which native speakers of English face, and therefore require different approaches to support2. Investigations carried out in England into the writing development, at Key Stage 2 and 4, of learners of English as a second, or additional, language, have shown that many of their difficulties correspond to those faced by native speakers of English, but that, in addition, they need specific additional support in the writing of extended discourse and in control of the grammar of English3. 1 Thomas, W, and Collier, V, A National Study of School Effectiveness for Language Minority Students’ Long-Term Academic Achievement, Berkeley, CA: Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence, 2001 (http://www.crede.org/research/llaa/1.1_final.html) 2 Landon, J, ‘Early Intervention with Bilingual Learners: towards a research agenda’, in South, H, Literacies in Community and School, Watford: National Association for Language Development in the Community (NALDIC), 1999, pp. 84–97 (http://www.naldic.org.uk) 3 Cameron, L, and Besser, S, Writing in EAL at Key Stage 2, London: DfES, 2004 (http://www.standards.dfes.gov. uk/ethnicminorities/resources/EAL_Writing_KS2_Oct04.pdf) Cameron. L, Writing in EAL at Key Stage 4 and post-16, 2003 (http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/publications/) languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Languages for Life is intended to be read in conjunction with Learning in 2(+) Languages, published in 2006 by Learning and Teaching Scotland, and available online at http://www.LTScotland.org.uk/inclusiveeducation/findresources/ learningintwopluslanguages.asp John Landon, formerly Head of Department of Educational Studies, Moray House School of Education, University of Edinburgh languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Introduction This publication is about language diversity. It provides guidelines for educational establishments that are seeking to promote the confidence of bilingual children4 in their own linguistic ability and language use. It also considers how language diversity provides a rich resource for all learners as they explore what language is, how it is used, and how it contributes to their understanding of the world. The information and recommendations contained here are of importance to all educational staff, no matter what the language profile of their establishment. Language is at the heart of children’s learning. Through language they receive knowledge and acquire skills. Language enables children both to communicate with others effectively for a variety of purposes and to examine their own and others’ experiences, feelings and ideas, giving them order and meaning. Children’s earliest language is acquired in the home5, and subsequent more formal educational experiences will build on that foundation. There are many children in educational establishments in Scotland whose home language is different from their language of education; it may be a variety of English which is different from the standard variety of English used for educational purposes. It may be Scots, Gaelic, or a language whose original home is far from Scotland – Arabic, Bahasa Malaysia, Bengali, Cantonese, Japanese, Kurdish, Lithuanian, Polish, Punjabi, Pushtu, Shona, Slovak, Urdu or Xhosa (to mention a number of the most commonly spoken home languages present in Scotland, according to recent school surveys). With the increase of overseas investment in Scotland, the necessity to address the skills shortage in Scotland by recruiting labour from overseas, the enlargement of the EU, and the arrival of new groups of refugees and asylum seekers, the number of children in educational establishments in Scotland whose home language is not English is growing and will continue to increase. In addition, as the population of Britain becomes more mobile, different regional and social varieties of English are becoming an increasing feature of Scottish classrooms. Educational establishments should welcome and exploit this linguistic diversity in order to raise achievement at all levels of education. 4 5 The word ‘bilingual’ is used throughout the document to describe pupils who come from homes or communities where languages other than English are spoken, and who in consequence are developing competence in these languages and in English. The term need not necessarily imply a high level of proficiency in two languages, although frequently it does. It describes pupils with a variety of language profiles, who have the advantage of being able to see the world through two sets of linguistic lenses. In this publication, the term ‘home language’ is used to refer to the language used in the home, when this is different from the language used as the medium of education. languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Bilingualism – an asset for all As far back as the Bullock Report of 1975, we read the following: ‘No child should be expected to cast off the language and culture of the home as he crosses the school threshold, nor to live and act as though school and home represent two totally separate and different cultures which have to be kept firmly apart.’ Six good reasons for encouraging the development of the home language: 1 Cheer home the front-runner! Even if you have never been to the Olympics, you know the cheer which erupts as the front-runner hits the final bend well ahead. In terms of a child’s linguistic and conceptual development, the front-runner is the language (or, in some cases, the languages) of the home. If the home language is Punjabi, the Punjabispeaking child at age 5 or 6 will have acquired, and be able to express, all the concepts which you would expect of an English-speaking child prior to entry into formal education. Through the medium of their home languages, no matter what those languages are, most children, by the age of 5, will have acquired concepts of number, size, shape, colour, cause and effect, and will also be gaining a whole host of social information, cultural nuances and values which will shape their developing sense of identity and perceptions of the world. They will be able to talk about possessions, feelings, relationships, hopes, fears, likes and dislikes. This learning cannot be unlearned, and does not need to be relearned if the home language is different from the medium of education. In the case of children who on entry to formal education will be developing as bilinguals, new labels for concepts will need to be acquired in English. There is no reason, however, why the home language should not continue to provide a strong foundation for learning, and gradually be joined, but not replaced, by English as the child’s confidence and competence in English develops. However, for the home language to continue to provide a viable and effective foundation, it needs to be promoted within the home. languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Children and their parents/carers will require every encouragement and support from the school or other educational establishment to persevere with the development of the home language, amid the pressures of their predominantly English-speaking environment. Educational practitioners should work with parents/ carers to help them to use the home language (or languages) when supporting their children’s learning through play and discussion arising from everyday activities, when reading to their children and when working with them as they develop writing skills in their home language. A recent video pack6 produced by the City of Edinburgh Council Education Department provides advice to educational establishments and to parents/carers on how they might do this. 2 Lead into reading It is natural that the child’s spoken language should be the ground in which initial reading and writing takes root. The child will talk and listen and be introduced to reading and writing in the home language at home. This provides the best foundation for developing these language skills in English. The foundations of reading and writing are laid before the child enters formal education. In a home where a language other than English is spoken, the written language with which the child first has contact will not be English either. In literate homes, parents tell stories and read to their children. Children see their parents reading and writing in, for example, Arabic, Chinese, Gaelic, Polish or Urdu. Within the community, children may see notices, posters and other forms of writing displayed in their home language, as well as in English. If they attend a place of worship, they will see and hear holy books being read. They will receive letters and cards written in their home language from family and friends elsewhere in Britain and overseas. The first experiences of reading and writing will relate to the language spoken at home and will be reinforced within the immediate family and community. In cases where families are not literate in the home language, children will not have as much exposure to the written language in their home language. They will, however, hear literature in oral form through stories and rhymes in their home language, which will contribute to their understanding of the forms of written language. 6 Supporting Young Bilingual Children and their Families is available from The City of Edinburgh Council Education Department, 10 Waterloo Place, Edinburgh EH1 3EG. languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Some children who have received education in their country of origin will enter educational establishments in Scotland already able to read and write in their home language. They will not have to learn to read and write again. They will merely have to adapt skills which they have already acquired to a different script. This is nowhere near as demanding as having to master entirely new skills through an entirely new language. Recent research7 into the acquisition of literacy by bilingual children has shown that they are frequently very good decoders of English, but that they require additional support with comprehension of English texts. This is because they are still developing their understanding of English grammar and vocabulary, and because the cultural allusions contained in the books they are reading may be unfamiliar to them. 3 Home confidence into school confidence Children develop strong bonds through the home language as they relate to family and friends. Also a sense of self, or individual identity, and a sense of belonging to a community begin to grow. With this growing sense of selfesteem, expressed through the home language, as children talk about personal experiences, joke and quarrel, show off and meditate quietly, they enter the English-speaking school or early learning setting. We cannot, nor would we wish to, change the language of education, but there is a lot we can do to ensure that the child’s growing self-esteem is not damaged, nor the pride in self and community knocked. There is much we can do, too, to affirm the parents/carers and community as they determine to keep alive, and cause to thrive, the home language and culture. In this way, strong bridges linking home and education can be built. A number of establishments employ bilingual support assistants who play an important role in developing and maintaining this point of contact. The active encouragement and use of languages other than English within the educational establishment also provide the stimulus for exploration of the different language experiences of all children in the class. It opens the way for useful discussion about language varieties, switching between varieties, attitudes to language, appropriateness and so on. Thus, all children are provided with the opportunity of owning, and gaining confidence in, their own language expertise. 7 See Gregory, E, Making Sense of a New World: learning to read in a second language, London: Paul Chapman, 1996. languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum 4 Bridges to partnership As home languages and culture are given a positive place within the educational establishment, parents/carers feel that a bridge has been built, not between home and hostile territory, but with an environment where they feel welcome and accepted, and where they have a stake. Thus, they will feel able to share in their children’s education. They will feel encouraged to offer their own contribution to the life of the school or nursery. They will also understand that the place where their child is being educated is a partner with them in strengthening their child’s commitment to home language and culture, rather than competing with them for their child’s linguistic and cultural allegiance. In this atmosphere, a happy partnership can form, which will serve the interests of the child, and which will enrich the lives of home, school and community. 5 The benefits of bilingualism The home language provides the starting-point for the development of English, and for learning through English. As the home language is promoted within family, community and education it continues to contribute powerfully to the child’s development as a thinker and learner. But the child has the added advantage of growing up as a bilingual. Research8 carried out in Britain and in many other multilingual societies worldwide has shown that those who become bilingual, with their home language strongly supported whilst their second language develops, experience definite cognitive benefits. 8 For a review of this research, see Baker, C, Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 4th edition, Clevedon, Avon: Multilingual Matters, 2006. languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Something of the nature of these benefits can be appreciated if we look at bilingual development through the following analogy. Jane has one pair of glasses with yellow-tinted lenses. To her the world looks only yellow. He can also wear the yellow and blue lenses at the same time and experience the merging of the colours into green, but recognise, unlike Jane perhaps, that the world is not yellow or blue or green but that one’s perception of the world depends very much on the lenses through which one views it. Further, Imran can share his kaleidoscopic world-view with Jane, confined within her yellow-tinted picture of reality. This analogy helps us to see why research shows that confident bilinguals tend to have: • well-developed deductive abilities, useful for problem solving and reading • facility for mathematical reasoning and for handling other symbolic systems • an awareness of the importance of context and audience in language use • strong potential for creativity and empathy • ability to talk about language and how it works • experience of learning two languages which is also an advantage when it comes to learning a third or fourth • potential for cross-cultural awareness and for translating across languages and cultures. These are all skills which are important for academic achievement. They are also skills which are likely to help bilingual pupils ‘to develop their capacities as successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens and effective contributors to society’.9 9 Imran has two pairs of glasses. One has yellow-tinted lenses. When he wears these, the world looks yellow. The other pair has blue-tinted lenses. When he wears these, the world looks blue. He has a choice of how to view the world – through yellow- or blue-tinted lenses. He can compare his different perceptions of the world with the different shades and tones which the different lenses highlight. He can choose when to wear the different lenses, and can share perceptions of the world with other yellow-tinted spectacle wearers, or compare perceptions with those wearing blue or any other colour of lens. Scottish Executive, A Curriculum for Excellence, Edinburgh: Scottish Executive, 2004 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum One wheel can get you places … So can a big wheel and a little wheel … However, when your wheels are nicely balanced and fully inflated you’ll go further … Provided, of course, the people who made the wheels knew what they were doing …10 6 Bilingualism is catching! Only as the educational establishment affirms and supports the development of bilingual children’s home languages, will these children gain confidence in sharing that language and the culture which it represents. However, no pressure must be put on children to share in this way. It must be left up to them to decide when and how opportunities for using or sharing the home language are embraced. When they do use their home language in the classroom or playground, bilingual children can provide an insight into a bilingual world for the benefit of monolingual classmates. Children who are able to function in only one language can appreciate the fascination of new sounds, symbols and expressions. They can also learn that fluency in more than one language is not only possible, but also desirable. In this way a positive attitude to foreign language learning can be promoted. Indeed, the first steps in language awareness and appreciation can be taken through sharing together the different languages, dialects and accents present in the learning environment, so that all children can increase in confidence and pride in their own rich linguistic repertoires. 10 Cummins, J, Bilingualism and Minority Language Children, Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, 1981. languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Recognising a child’s language assets ‘Language is a treasure chest. And my child is richer by every language he knows.’ Parent 10 All education establishments can maximise the value of the language assets invested in them. They can maintain their currency, increase the exchange rate, and draw off the interest for the benefit of everyone. We have already seen the investment potential for children’s general learning and language learning which bilingualism represents. In addition, these children will grow up and leave school with greater language expertise, which will serve to enhance their earning potential and form the basis for lifelong learning. The alternative is that, for lack of a shrewd language investment policy within the educational establishment, the currency of the home language is devalued for everyone in the community, and what had value in the home ceases to become legal tender within the school or nursery, and within the wider community. The child feels inhibited in using it; the child’s parents/carers feel discouraged about supporting it. Everyone within the community is denied the benefits of a rich resource. Thus, children who enter education with the potential of doubling, at the very least, their language investment capital leave with the value of that capital halved. That is a scenario of educational failure, on the part of the education system, which must be avoided at all costs. The first task for the educational establishment is to recognise what language assets the child possesses. To take the analogy further, this process will involve the shareholders – parents/carers, other community members, teachers, fellow pupils and other educational practitioners, and, of course, the child. Investment growth will need to be reflected in reports on the child, in personal learning planning, and in the overall multilingual profile which the educational establishment presents internally and to the outside world. languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum 1 Enrolment As the child comes to enrol in the educational establishment, it is helpful if the headteacher or senior manager and other staff can greet the child and his or her family in the home language11. The enrolment form should include a question about languages used for speaking, reading and writing at home. This question should be addressed to every parent/carer. If a parent/carer queries why the information is required, it is a good opportunity to explain the policy towards bilingualism and towards non-standard varieties of English. When a language other than English is used in the home, further questions can follow about the family’s ability to support the child’s reading in that language, the requirement for documents to be translated and the necessity for interpreters to be present when parents/carers wish to discuss their child’s progress. 2 Observation and profiling It is important for the educational establishment to know the child’s level of competence in, and through, the home language. If the child has already received some education through the medium of the home language, the level of development of language and mathematical skills and the grasp of concepts will need to be discovered, through the child’s first language, so that appropriate provision can be planned. If the child already knows some English, the level of competence in English will also need to be assessed. Some establishments have access to bilingual teachers, other educational practitioners or classroom assistants who are of inestimable help in this process. Others can draw on the services of family or community members who share the same language as the child. They will require clear induction and support before carrying out observation and profiling. Where no such help is available, English as an Additional Language (EAL) support services may be called upon to give advice to educational practitioners on home languages, and on the assessment of English as a second, or additional, language. Useful sources of advice Useful websites can be found in Appendix A of Learning in 2(+) Languages.12 11 For useful words and phrases for welcoming new arrivals in over 800 languages, see: http://www.elite.net/~runner/jennifers/hello.htm 12 Available on: http://www.LTScotland.org.uk/inclusiveeducation/findresources/ 11 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum 3 Involvement of parents/carers Scottish education policy recognises the prime educating role of the parent/ carer. This is true whether the parent/carer is a native speaker of English or not. Parents/carers can provide very valuable information about their children’s home language ability. They will know how effectively their children use the language in different contexts and for different purposes. As they read to, and with, their children, parents/carers will gain insights into their child’s literacy development. They will also pick up any problems which their children have in using the home language and will be able to communicate that to the educational establishment for consideration and action. Educational practitioners will need to support parents/carers in this partnership. Some parents/carers may have adopted the attitude that home language development interferes with academic success. Staff within the educational establishment will need to convince them of the inaccuracy of this perception. All parents/carers require advice on how to assess their child’s progress, what to look for, and how to report it to the school or other educational establishment. This advice may need to be communicated in the home language. Some parents/carers may not have access to books in their home language. A range of dual-language books (books written in both English and another language) is now available, and can be loaned to parents/carers by the educational establishment or the local library. Parents/carers will need to be kept informed about the learning opportunities their children are receiving within the educational establishment and how they can support their children’s learning at home. If parents/carers are concerned about their child’s development or progress, they need to have free access to practitioners in the educational establishment, their concerns need to be taken seriously and their requests for action met13. Parents should be involved in discussions with the educational establishment as decisions about their child’s 13 12 A Curriculum for Excellence (2004) emphasises the importance of educational establishments providing parents with ‘a clear understanding of the learning opportunities their children should have, ways in which they can support their children’s learning; the purposes of these activities; and the recognition which children will receive for their achievements’. See the terms of the Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004. languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum education are made and should be kept informed of action that is being taken to support their child. In some cases this will mean that trained and qualified interpreters14 will be required, to ensure that the parents/carers may be fully informed about their child’s progress, and to guarantee that full confidentiality is maintained. Useful sources of advice Information about, and links with, publishers of multicultural and dual-language resources can be found at: http://www.literacytrust.org.uk/rif/projectresources/ specialist_publishers.htm EMA online (http://www.emaonline.org.uk/ema) is an online resource base for teachers developed by Birmingham, Leeds and Manchester local education authorities. It contains materials for primary schools and for certain secondary subject areas (for example, science) in a number of home languages. 4 Reporting: promoting partnership with the home ‘School reports communicate information about pupils. Effective communication depends upon mutual understanding. Parents need to know what the school is trying to do and to recognise the knowledge, skills and attitudes which the school seeks to impart. Teachers need to be aware of parents’ aspirations and concerns. A good report is one which promotes this vital communication between home and school.’ Reporting 5–14: National Guidelines (Scottish Office Education Department, 1992) The promotion of ‘better, more flexible parental involvement in their children’s learning’ is one of the commitments of Ambitious, Excellent Schools: our agenda for action (Scottish Executive, 2004). Effective reporting is part of a process of promoting partnership with the home. When the child’s parents/carers and educational practitioners more or less share the same language and culture and have the same experience and expectations of education, this process is usually fairly straightforward. However, when language and culture are not shared, 14 For information about the National Register of Public Service Interpreters, see http://www.iol.org.uk/nrpsi 13 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum and when a common view of the purpose or conduct of education cannot be taken for granted, misunderstandings and bewilderment are more likely to occur on both sides. The risk is greater when children from ethnic and linguistic minorities are few in number15, and are enrolled in educational establishments in communities where intolerance and discrimination are widespread. First of all, it is essential that educational establishments adopt policies on multicultural and antiracist education and on how to deal with racist incidents. It is also necessary for educational managers to ensure that policies clearly express their establishment’s position and practice with regard to home languages which are different from English, and demonstrate a positive approach to the development of bilingualism. These policies should be carefully implemented, and their implementation monitored and periodically reviewed by all staff, with the involvement of parents/carers. They also need to be made available to all parents as a matter of course, in languages other than English where necessary. Parents/carers from ethnic and linguistic minority groups may feel reticent about involvement with the school or other educational establishment. They may not be sure of their acceptance or their role. They may be deterred by their poor command of English. Their domestic circumstances may make it difficult to attend events at certain times of the day. The fear of racist harassment may prevent them coming out after dark. The educational establishment must take positive steps to create links and to develop partnership by the provision of interpreters, by encouraging visits to the establishment at any time, by arranging home visits, and by facilitating parental participation in activities and decision making. Some establishments have done this by organising activities for parents/carers, such as language and literacy classes, cookery demonstrations or recreational activities, on school premises during the day. Some regularly involve parents/ carers in their children’s learning, through paired reading schemes, or as helpers. It is important that, when parents/carers from ethnic minority groups are involved in this way, they participate in the same way as all other parents, and not merely as representatives of an ‘exotic’ way of life. As an ethos of partnership is developed, effective communication, dependent upon mutual understanding, will be all the more possible. This applies in the most obvious instances, for example correct pronunciation and spelling of the child’s name and basic awareness of the child’s cultural and linguistic background (although direct questions can also be used to find out such information). It also 15 14 For more information about the particular issues facing isolated bilingual learners and their families, see Aiming High: Understanding the Educational Needs of Minority Ethnic Pupils in Mainly White Schools (DfES, 2004), which can be downloaded from http://www.standards.dfes.gov.uk/ethnicminorities/links_and_publications languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum involves the avoidance of stereotyping and of jumping to ill-informed conclusions. When a child is developing as a bilingual, reports on language ability should, if possible, reflect progress in the home language as well as in English. The report should focus primarily on the child’s success and development in relation to each curriculum area. The child will be making progress in the development of knowledge, skills and attitudes even though competence in English might be limited. When reporting on English language successes and needs, it is important not to base comments on unfair comparisons with native speakers of English, nor to concentrate merely on areas in need of development. A description of success and progress and the highlighting of strengths are crucial to a report and are likely to have a significant effect on the pupil’s motivation and upon the parents’ confidence in the education their child is receiving. Useful sources of advice The Centre for Education for Racial Equality in Scotland (http://www.education. ed.ac.uk/ceres/) provides useful advice about policy and practice. The Anti-Racist Toolkit (http://www.antiracisttoolkit.org.uk) provides valuable staff development information on Scottish race relations legislation and anti-racist practice. The Moray inclusion files contain useful practical strategies for implementing inclusion policies in general and race equality strategies in particular. They are available at http://www.LTScotland.org.uk/ inclusiveeducation/findresources/moray/index.asp Translated school letters in a variety of home languages can be downloaded at http://www.dgteaz.org.uk. 15 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Realising a child’s language assets Although most establishments do not have access to bilingual staff, there is still much that can be done to support children’s home languages with the help of parents, community and the children themselves. ‘We were focusing on the ways that the knowledge and abilities brought to school by monolingual English children could be built on and extended. Surely there was no reason why this basic tenet of education had to be suspended in relation to the schooling of bilingual children? We reminded ourselves that in our school, the focus was not on what children lacked but upon teaching and support for their development. So quite logically, our next step had to be to look for ways of extending children’s bilingualism and of responding to the cultural diversity of the school.’ Primary headteacher As this primary headteacher expresses it, the first step is commitment to support the child and his or her family to realise that child’s home language assets. Several practical steps can be taken in any school. 1 Environment and ethos Reflect the various languages in the community which the school or other educational establishment serves, by providing signs and posters in the entrance foyer, office and other public areas which welcome people in the different languages of the community and celebrate the commitment to bilingualism. Use parents or other community members to produce bilingual posters, notices, labels and captions for display around the school.16 16 16 Words and classroom labels can be downloaded from Hounslow Virtual Education Centre at http://www.hvec.org.uk/HvecMain/index.asp. On the ‘Documents and Forms’ page, search the A–Z List of Documents for ‘Classroom Topics – Multi-lingual Words’. This page contains labels, words and common phrases for classroom use and for use in a number of topic areas. The following languages are covered: Albanian, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Panjabi, Spanish, Somali, and Urdu. languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Encourage parents whose home language is other than English to help in the classroom, library and playground, and in other activities, and to use their home language whenever possible. Incorporate greetings and information in various home languages in newsletters and other communications. Have a policy of communicating with parents/carers in the home language, wherever this is necessary, through the use of translated written communications and interpreters. 2 Supporting learning Where possible, provide opportunities for children from the same home language background to communicate with one another in their home language, for example in pair or group work, on some occasions. Provide books written in different home languages, including dual-language books, in reading corners and the library. Demonstrate a positive approach to children spending time visiting relatives overseas. Encourage parents/carers to give plenty of notice so that tasks can be set for the child to complete which will make use of the home language and involve gathering material for display and use on return to Scotland. Use material gathered during the visit as the basis for a class project. Acknowledge the child’s home language achievements in displays and in the establishment’s newsletter as well as in the child’s report. This may involve liaison with community-based supplementary language classes. Provide opportunities for children to study their home language or the home language of their peers in extra-curricular clubs or during free-choice periods, or as examination subjects within the mainstream curriculum. 17 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum 3 Opportunities for home language development within the 3–18 curriculum Language Invite parents to tell stories in languages other than English. Encourage children from a different home language background to speculate on the meaning of the story from the gestures, expressions, pictures and props used by the storyteller. This is an excellent listening activity for all children. Encourage children who feel confident to use their home language to write stories or poems in a home-language or dual-language version for use in the classroom, and to produce contributions in the home language (with English translation) for the newsletter or school magazine or for publication and display. Software packages are available in a number of different scripts.17 Give children the opportunity to use home languages during assemblies or class presentations. Respect the fact that the child may not take up the opportunity. Explore language themes, using the language expertise present in the classroom, for example language families and word borrowings and their histories, proverbs, metaphors, writing systems and famous authors. Provide the opportunity for all children to learn common expressions in the languages present in the community and to try them out. Study works of literature in their original version and in their English translation and compare the two. Mathematics Explore numbering systems in different languages and observe patterns in writing numbers (for example, in Chinese). Encourage children to do computations using their home language numbers. Learn number rhymes in different home languages. 17 18 Fabula (http://www.fabula.eu.org) is a software package for making bilingual multimedia stories. The software can be downloaded for free. Lingua (http://www.lingua-uk.com) is a company which sells software packages in a number of ethnic minority languages. For a case study on the use of Clicker multilingual software in an early education setting, see http://www.LTScotland.org.uk/earlyyears/ictinpreschool/casestudies/killermont.asp languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Expressive arts Listen to, and perform, songs and rhymes in various home languages. Produce drama scripts and perform drama involving the use of different languages. Use different writing systems as the basis for calligraphy and design. Play games which involve using different home languages (for example, versions of ‘Simon Says …’). Watch people using different languages on film or video and talk about gesture, sound, film techniques. Compare reporting of world events in the mass media in different languages. Environmental studies Use different languages for projects in the local community (for example, interviewing local residents, collecting life stories). Collect information from other communities, in Britain or overseas, by writing and receiving letters in various languages. Organise an educational link to exchange information or topic work through letters, e-mail, podcasting, blogging and/or videoconferencing. This may lead to an exchange of visits which need to be sensitively and carefully set up over an extended period, with careful briefing of pupils and parents/carers, to avoid misunderstanding or cultural voyeurism. In history, use source material written in different languages, using children as translators. 19 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum 20 Religious and moral education Consider the importance of language in communicating and practising religious beliefs, for example different views on translating holy books from one language into another, and the use of the ancient forms of the language for acts of worship. When referring to religious practices, wherever possible use the term in the original language. Modern languages Provide the opportunity for children to study their home language to examination level. Consider the global distribution of languages like Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, French and Spanish. Consider loan words from different languages (for example, Arabic words in French). Develop a language awareness topic, with contributions reflecting the linguistic diversity of the learning group. Recognise the fact that children often act as translators or interpreters within their home or community. languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum As the following diagram shows, there are benefits for all children in supporting bilingualism across the curriculum. The benefits derive from the principles of equality of opportunity, developing skills and talents that children bring to their education and responding positively to a multicultural society. Basic principles • Enhances equality of opportunity and social inclusion • Develops skills and talents that children Benefits for bilingual children • Supports learning bring to their education • Responds positively to a multi- • Aids intellectual/cognitive development • Supports self-esteem/confidence in own ethnicity culturaL society • Supports relationship with family and community • Extends vocational and life options Benefits for educational practitioners • Increases knowledge of, and relationship with, individual pupils and their families • Develops recognition of pupils’ family/community as a resource • Enhances awareness of linguistic and cultural diversity • Strengthens links with the communities served by the educational establishment • Contributes to multicultural ethos of the establishment • Provides early warning of language and learning difficulties Benefits for all children • Supports confidence in own language skills • Increases language awareness • Contributes to combating racism • Increases awareness of cultural diversity • Enhances communication between different groups Adapted from: Houlton, D, and Willey, R, Supporting Children’s Bilingualism, Harlow: Longman, 1983 21 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Building upon the home language – development of English as a second, or additional, language (EAL) A major objective of educational planning and provision must be to support the development of English as an addition to, and not at the expense of, the home language. It is equally clear that, in the same way as the home language is important to ensure continuity in intellectual and social development, English must also be acquired to a high level to enable bilingual children to reach their full academic potential. The effective acquisition of English is not an automatic process. To develop and flourish, the second or additional language requires certain conditions and sustained support. These are not unlike the conditions necessary for native speakers of English as they extend their control of their home language to meet the new demands of the primary classroom and develop their skills in talk and listening to master reading and writing. Children starting from a base in a language other than English require teachers and other practitioners to pay more specific attention to the language and cultural demands of classroom activities, and to the support provided within the learning environment for the development of language and learning. Recent research18 has provided us with many helpful insights into the process of second language acquisition. This can help us to plan learning activities and to organise support so that the conditions for healthy second language growth are met. Gardener’s question time: Why are my bilinguals withering while my English monolinguals are doing so well? Answer: They thrive when they grow together, but bilinguals need plenty of support. 18 22 For an overview of research, see: Bilingual Development in the Early Years – an overview of research at http://www.LTScotland.org.uk/inclusiveeducation/aboutinclusiveeducation/researchandreports/index.asp languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum The process of second language development A learning environment with plenty of talk and listening, where children are encouraged to interact and where there is clear visual support for learning is the best place for second, or additional, language development. 1 Plenty of listening time is important Children learning their first language spend about a year as active listeners, as they tune into the sounds and meanings of the language around them. Children developing as bilinguals also need time to tune into the sounds and meanings of their second, or additional, language. Most will not take as long as a year before they speak, although the length of time varies depending on personality, learning style and other individual differences. They need to hear many examples of English being used so that they can start to construct their own model of the language. Listening time means looking time too. Children new to the Scottish education system who are also new to English particularly need time to watch, to scan and absorb the routines of the learning environment before being expected to participate in them enthusiastically and confidently. Some children remain silent for what seems a very long time. Practitioners, by providing plenty of visual support for learning and by involving children in play and learning activities, will be able to observe whether silent children are watching and learning. Discussion with parents/carers often reveals that children who are silent at the early stages of learning English were also slow to speak in their home language. Frequently the door to talk is eventually unlocked as the child engages in an exciting or culturally relevant activity and is desperate to talk. Then the results of months of the child listening and watching are plain to hear! The child may not understand much of what he or she hears. What may not be understood through the ears may be interpreted through the eyes, if plenty of visual support for meaning is provided during learning activities. 23 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum 2 Visual support for meaning Meaning can be conveyed with the help of pictures, key visuals, actions or demonstrations rather than relying on the language alone to put the meaning across. For example: • supporting storytelling with pictures, which can later be used by pupils as a support in retelling the story • demonstrating number work with real objects, preferably culturally familiar objects • providing pictorial as well as written instructions for investigations, problem solving, or practical activities, like cooking, or demonstrating the activity step by step with the child imitating each step • as children work in groups on repetitive activities, like turn-taking games or investigations, let other children take their turn first so that they can demonstrate the activity to the bilingual child • representing the relationship of key concepts in the form of key visuals, such as flow charts, timelines, matrices and charts. 3 Other children can be the best teachers Children are not just passive recipients of new language. They also need opportunities to try out the language they are learning. These opportunities are provided most effectively when pairs or small groups of children engage in activities together within a structured and well-planned learning environment. Research19 shows that more proficient speakers of a language modify their speech to support the understanding of their less proficient partners. In the interests of sharing meaning, they explain words, expand phrases, and reorganise sentences in ways which not only stretch them linguistically and intellectually, but also provide the raw data essential for the acquisition of English. The presence of bilingual learners gives native speakers of English a unique opportunity to learn at first hand about the nature of language and of effective communication.20 The need to modify English to make meaning clear is cognitively and linguistically challenging for an able and articulate native speaker of English as the following example shows: 19 For an overview of research into second language acquisition see Ellis, R, The Study of Second Language Acquisition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994 20 Many further examples of this type of modification, the learning activities which promote it, and the benefits for English native speakers and English language learners are found in Gibbons, P, Scaffolding Language, Scaffolding Learning: teaching second language learners in the mainstream classroom, Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2002. 24 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Child B (English language learner) Child A (native speaker of English) What does Child A do to make meaning clear to Child B? Have you got your strong shoes? I have got on my shoes. Yes, but your shoes. The shoes that don’t let … that don’t get your feet wet. EXPLAINS the meaning of strong (here used in an idiomatic sense). Do you like to jump in puddles? RECOGNISES THAT CHILD A HAS NOT FULLY GRASPED MEANING. REPHRASES to make the phrase simpler and to avoid the difficult verbal phrase – that don’t let the water in. My feet not wet. FINDS ALTERNATIVE WAY OF PUTTING THE MEANING ACROSS Puddles? Puddles – water on the floor. EXPLAINS the meaning of puddles in response to Child B’s request for clarification. Your feet get wet? Not wet now? Have you got your … trainers? MATCHES the telegraphic sentence construction used by B. No, I get wet. My feet wet. INTRODUCES trainers – a word which might be known to B. Trainers? If your feet get wet, you put trainers on … like in there in the hall. USES CONCRETE EXAMPLE – like in there in the hall. If your feet GET wet. Trainers on (demonstrating wildly). USES GESTURES as a last resort. My feet? 25 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum 26 4 English is best acquired through mainstream learning activities Children learn their first language not as an end in itself but as a means of learning about the world around them. Similarly, the learning of a second, or additional, language happens most effectively when the focus is not on learning language, but on learning something else through that language. The kind of talk which best facilitates second language acquisition is achieved through activities which involve the repetition of certain actions or processes. These activities support learning, but incidentally they provide the opportunity for the rehearsal and consolidation of a range of English language structures. Learning activities which provide opportunities for incidental repetition of English structures: • stories with repeated phrases or themes, for example: The Gingerbread Man • game-like activities in which the same or similar moves are repeated, for example: Happy Families • problem-solving activities which involve formulating and testing a number of hypotheses in the search for a solution to a problem • investigations which involve asking the same or similar questions about different objects (for example, describing the appearance and behaviour of different minibeasts or investigating the properties of solid shapes) or exploring a natural phenomenon under different conditions (for example, the height of bounce of balls made of different substances when dropped onto different surfaces) • physical or musical activities which involve the sequencing of movements or sounds • a series of activities which enable the bilingual learner to become an expert in an area of knowledge and then to pass on that knowledge to others. languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Activities should be set at the intellectual level of the bilingual learner, and not kept at an intellectually undemanding level merely because of the learner’s limited English language competence. Where competence in English impedes access to the activity or to the curriculum generally, support can often most effectively be given by planning a series of interrelated activities, as the following example shows. Here the activities progress from being relatively undemanding to being more demanding. Support for understanding is also gradually reduced. This is nothing other than good teaching. Series of interrelated activities Examples from mathematics Activity A English which pupils might use Investigating the property of solid shapes: cube, cuboid, cylinder, cone, hexagonal prism, pyramid Does this one stack? Let’s see if this one rolls. It rolls but it doesn’t stack because it’s pointed. (SUGGESTING, DESCRIBING, GIVING REASONS) B Entering the data on a grid A cylinder stacks, so put a tick there. And it rolls, so put a tick in the box. Do you mean here? No, not there. A cube doesn’t roll. (DRAWING CONCLUSIONS, CHECKING MEANING) C Interpreting the grid through a guessing game I’m thinking of something which rolls but doesn’t stack. Is it a cylinder? No, it doesn’t stack. (DESCRIBING HYPOTHESISING, AGREEING AND DISAGREEING) D Extending this investigation into the properties of solid shapes by thinking about why chocolate bars and boxes of chocolates are of certain shapes They’re usually cuboids because they stack. They’re easy to store. Sometimes you can get pyramids. That’s because … you don’t find cones though. (GIVING REASONS, DESCRIBING PURPOSE, DRAWING CONCLUSIONS) 27 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Activities which are most effective for encouraging learning in general and language learning in particular are those which are meaningful to the child. They should have a purpose which is clear and which makes sense. As far as possible they should be based within a cultural context which is familiar to the child. This applies particularly to reading and writing activities. Reading essentially meaningless sentences or isolated words, and writing sentences out of context, does not promote language development. However, reading and writing about events which are within the child’s experience and derive from the child’s own cultural background provide exactly the right stimulus for language use and language learning. Such activities will derive their meaning and purpose from the ongoing development of a multicultural curriculum. 5 Errors are often a sign of language growth As children discover how English works, through exposure to the language in meaningful contexts, they will want to experiment with the English they have acquired. However, it is very unlikely that the English which a child uses will correspond initially to native-speaker usage. These errors are a sign of growth. Over time, the English produced in talk or writing will come to approximate nativespeaker usage more and more closely, as long as adequate exposure to English is maintained, and there is plenty of opportunity for interaction with other pupils. The child’s approximate version of English will show itself in the spoken and written language. It will also be evident when the child reads aloud. A child who is reading for meaning will make the same pronunciation and grammatical errors when reading aloud as are made during talk. All such errors should be handled sensitively and with encouragement through formative assessment of writing during the drafting and redrafting stages. As the child uses English in talk, the emphasis should be on how effectively the child communicates and understands (errors included) rather than on how correctly he or she uses English, in the early stages at least.21 As part of assessment for learning, it is important that common patterns of error are pointed out to the more mature learner, and further opportunities for practice of the correct form introduced into learning activities. Checklists of a learner’s common errors, drawn up as part of personal learning planning, provide a helpful basis for self or peer editing. . 21 28 Information about the kinds of difficulties which speakers of a range of home languages are likely to face when learning English can be found on the Portsmouth EMAS Home-School-Community Project website: http://www.blss.portsmouth.sch.uk/hsc languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Conclusion The presence in our education system of children developing as bilinguals provides us with a challenge which will benefit everyone within the learning community. Their home language gives all children an insight into another language and another culture. It provides the opportunity to learn how to communicate in spite of language and cultural barriers. This is an experience so important in our increasingly interdependent world. The support they require for the development of English language for the curriculum opens our eyes afresh to the language demands which different learning activities pose. This should stimulate us to review the educational establishment’s language policies with renewed urgency, to ensure that they are relevant to, and inclusive of, the language development of all children. Effective communication between children, between children and teachers or other practitioners and between the educational establishment and families and the community it serves is vital for good relations. This is particularly true in a multicultural context. Effective communication is the key to effective learning. 29 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Checklists for action 30 Policy • In the establishment’s language policy: – is the benefit to all of recognising and exploring language diversity represented? – is there a commitment to home language development? – is there a commitment to provide English language support for the mainstream curriculum? – is the role and function of EAL support teachers and bilingual support staff (where available) made clear? • Is guidance given on how these aspects of the establishment’s language policy can be achieved? • Are all teachers and other practitioners involved with bilingual pupils made aware of the establishment’s policy? • Is the policy made available to parents/carers in a form and in a language which they can understand? • Is implementation of the policy regularly monitored, and are modifications to procedures, practice and provision made as a result? Ethos • Is the establishment’s ethos sensitive and open enough for children to feel free to own and use their home languages during play and learning activities? • Are children’s diverse linguistic skills celebrated and acclaimed in different spheres of the establishment’s life? Professional development • Are all practitioners aware of the benefits of maintaining and developing children’s home language(s)? • Are all practitioners able to provide appropriate support in EAL to children developing as bilinguals, at all stages of their English language development? • Are all practitioners aware of the most effective ways of cooperating with support staff in making the curriculum more accessible to bilingual pupils? languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Partnership with the home and community • Are the establishment’s procedures and practice with regard to languages other than English equally inclusive of all languages? • Are records kept of the home languages of children? Are these records available to all practitioners? • Where appropriate, are trained interpreters used, and translations made, to ease communication with parents/carers whose English is limited? • Are parents/carers kept informed of the educational establishment’s policy and practice? • Are parents/carers kept fully informed of their child(ren)’s development and are they fully involved if their child’s progress or behaviour is giving cause for concern? • Are references to the development of the child as a bilingual made in reports on the child? • Are parents/carers actively encouraged to participate in the life of the educational establishment? • Are parents/carers encouraged and enabled to support their child’s development of the home language and general learning? Classroom practice – home language development • Do children use home languages in the learning environment to communicate with other children from the same language background? And do they contribute to discussion out of their experience of being bilingual and knowledge of a language/languages other than English? If they do not, do practitioners know what might be inhibiting them? • Are opportunities taken to explore language diversity across the 3–18 curriculum? • Are opportunities provided for learners to study their home languages at examination level? • Is children’s fascination with language and languages exploited? 31 languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum Classroom practice – second, or additional, language development 32 • Is support for English language development provided within the mainstream learning environment as a matter of course? Is this support maintained to ensure that English is not a barrier to access to the curriculum? • As part of assessment for learning, is a constant check kept on bilingual learners’ understanding of curriculum content and their ability to communicate their understanding in talk and writing? • Is plenty of visual support for meaning available to the bilingual learner, even beyond the early stages of acquiring English? • Is there good opportunity for meaningful and purposeful interaction between pupils during learning activities? • Is the bilingual child included as a working member of a facilitative and supportive group (preferably of able and articulate native speakers of English) within the learning environment? • Is the cultural base for learning activities familiar to the bilingual child? Are opportunities provided for children to share from their own cultural and life experience if they wish to? • Is the approach to English language errors sensitive and supportive, with the main emphasis on the quality of the content and not the accuracy of expression, at least in the early stages of ESL acquisition? At later stages of English language acquisition are errors in written work carefully discussed, and are opportunities provided for redrafting? • Are accurate and up-to-date records kept of the child’s general learning and of the child’s EAL development? • Are bilingual learners supported with the English of more intellectually demanding activities, even though they may be socially fluent, so that they may reach their full academic potential? • As part of personal learning planning, are practitioners setting clear and challenging targets for the learning and English language development of bilingual learners? Are learners involved in this process? Is the achievement of targets regularly reviewed and are new targets set or negotiated? Are parents/carers kept informed of this process? • If there are causes for concern about other additional learning needs in a bilingual child’s development or progress, are appropriate practitioners involved in discussing the case and in planning additional support for learning? Are the child’s parents/carers fully informed of, and involved in, the process? languages for life across the 3–18 curriculum References Baker, C, Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 4th edition, Clevedon, Avon: Multilingual Matters, 2006 Cameron, L, and Besser, S, Writing in EAL at Key Stage 2, London: DfES, 2004 (http://www. standards.dfes.gov.uk/ethnicminorities/resources/EAL_Writing_KS2_Oct04.pdf) Cameron, L, Writing in EAL at Key Stage 4 and post-16, London: Ofsted, 2003 (http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/publications) Cummins, J, Bilingualism and Minority Language Children, Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, 1981 Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004, Edinburgh: The Stationery Office, 2004 Ellis, R, The Study of Second Language Acquisition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994 Gibbons, P, Scaffolding Language, Scaffolding Learning: teaching second language learners in the mainstream classroom, Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2002 Gregory, E, Making Sense of a New World: learning to read in a second language, London: Paul Chapman, 1996 Houlton, D, and Willey, R, Supporting Children’s Bilingualism, Harlow: Longman, 1983 Humby, T, and Watson, S, Supporting Young Bilingual Children and their Families is available from the City of Edinburgh Council Education Department, 10 Waterloo Place, Edinburgh EH1 3EG Landon, J, ‘Early Intervention with Bilingual Learners: towards a research agenda’. In South, H (ed), Literacies in Community and School, Watford: National Association for Language Development in the Community (NALDIC), 1999, pp. 84–97 (http://www.naldic.org.uk) Scottish Executive, A Curriculum for Excellence, Edinburgh: Scottish Executive, 2004 Thomas, W, and Collier, V, A National Study of School Effectiveness for Language Minority Students’ Long-Term Academic Achievement, Berkeley, CA: Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence, 2001 (http://www.crede.org/research/llaa/1.1_final.html) 33 Learning and Teaching Scotland, The Optima, 58 Robertson Street, Glasgow G2 8DU T: Customer Services 08700 100 297 E: enquiries@LTScotland.org.uk www.LTScotland.org.uk