The Maturing of the MOOC BIS RESEARCH PAPER NUMBER 130

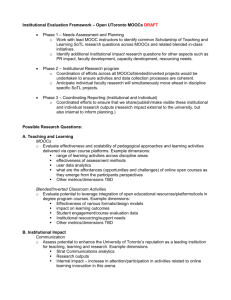

advertisement